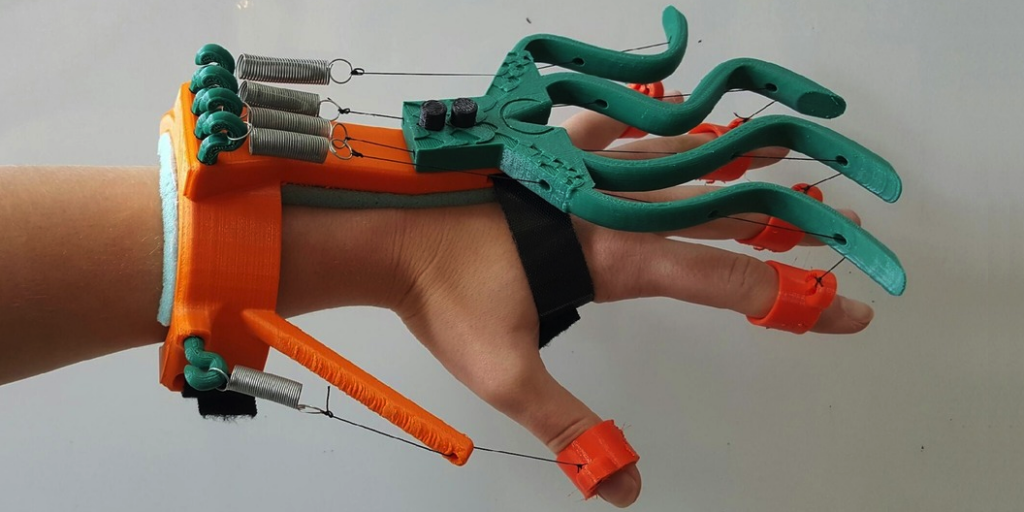

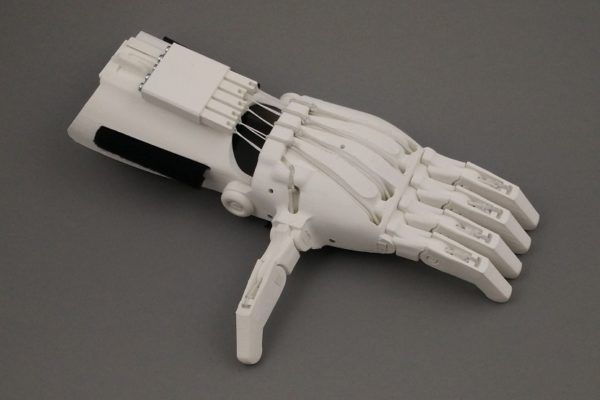

3D printed prosthetics hand

3D-printed prosthetic limbs: the next revolution in medicine | 3D printing

John Nhial was barely a teenager when he was grabbed by a Sudanese guerrilla army and forced to become a child soldier. He spent four years fighting, blasting away on guns almost too heavy to hold, until one day the inevitable happened: he was seriously injured, treading on a landmine while he was on morning patrol.

“I stepped on it and it exploded,” he recalled. “It threw me up and down again – and then I tried to look for my leg and found that there was no foot.”

His comrades carried him back to base camp, but there was hardly any medical care available. It took 25 days before he received proper treatment, during which time he developed tetanus down one side of his body. Finally, Nhial (not his real name) was put on a flight to the Kenyan border, his life only saved when he was handed over to a Red Cross team.

Now, a decade later, he lives in a Juba refugee camp, having suffered further troubles in the conflict that has engulfed the struggling new nation of South Sudan. He plays wheelchair basketball for his country, although he relies on a prosthetic lower leg to struggle around the muddy, sprawling camp. Reaching the most basic services often entails long walks and it can be difficult to get to training. But at least his hands are free to carry things such as food and water, unlike those on crutches.

Such stories of lives devastated by conflict or disease are all too common in developing countries. Lack of an arm or leg can be tough anywhere, but for people in poorer parts of the world it is especially challenging. Some are victims of conflict, while others may have been born with congenital conditions. Many more are injured on roads, with the casualty toll soaring in poorer nations. In Kenya, half the patients on surgical wards have road injuries. The World Health Organization estimates there are about 30 million people like Nhial who require prosthetic limbs, braces or other mobility devices, yet less than 20% have them.

Prosthetics can involve a lot of work and expertise to produce and fit and the WHO says there is currently a shortage of 40,000 trained prosthetists in poorer countries. There is also the time and financial cost to patients, who may have to travel long distances for treatment that can take five days – to assess their need, produce a prosthesis and fit it to the residual limb. The result is that braces and artificial limbs are among the most desperately needed medical devices. However, technology may be hurtling to the rescue – in the shape of 3D printing.

There is also the time and financial cost to patients, who may have to travel long distances for treatment that can take five days – to assess their need, produce a prosthesis and fit it to the residual limb. The result is that braces and artificial limbs are among the most desperately needed medical devices. However, technology may be hurtling to the rescue – in the shape of 3D printing.

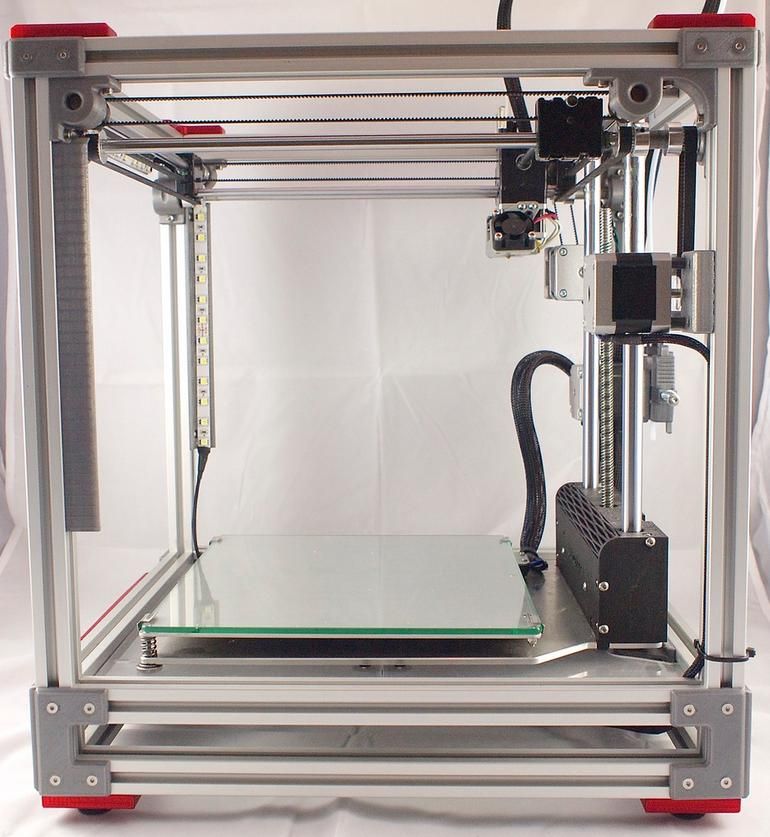

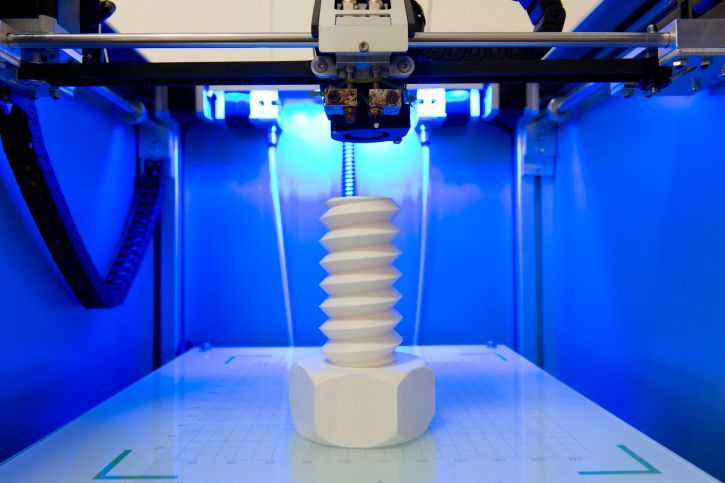

Slowly but surely, 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, has been revolutionising aspects of medicine since the start of the century, just as it has had an impact on so many other industries, from cars to clothing. Perhaps this is not surprising, given that its key benefit is to enable the rapid and cost-efficient creation of bespoke products. There are few commercial products that need to suit a wider variety of shapes and sizes than medical devices made for human beings.

Experts have developed 3D-printed skin for burn victims, airway splints for infants, facial reconstruction parts for cancer patients, orthopaedic implants for pensioners. The fast-developing technology has churned out more than 60m customised hearing-aid shells and ear moulds, while it is daily producing thousands of dental crowns and bridges from digital scans of teeth, replacing the traditional wax modelling methods used for centuries.

The fast-developing technology has churned out more than 60m customised hearing-aid shells and ear moulds, while it is daily producing thousands of dental crowns and bridges from digital scans of teeth, replacing the traditional wax modelling methods used for centuries.

Jaw surgery and knee replacement operations are also routinely carried out using surgical guides printed on the machines. So it is no surprise that the technology has begun to stir interest in the field of prosthetics, even if sometimes by accident. Ivan Owen is an American artist who likes to make “weird, nerdy gadgets” for use in puppetry and budget horror movies. In 2011, he created a simple metal mechanical hand for a steampunk convention, the spiky fingers operated by loops pulled through his own.

He posted a video that was seen by a carpenter in South Africa who had just lost four fingers in a circular-saw accident. They began discussing plans for a prototype prosthetic hand and that came to the attention of the mother of a five-year-old boy, called Liam, who had been born without fingers on his right hand.

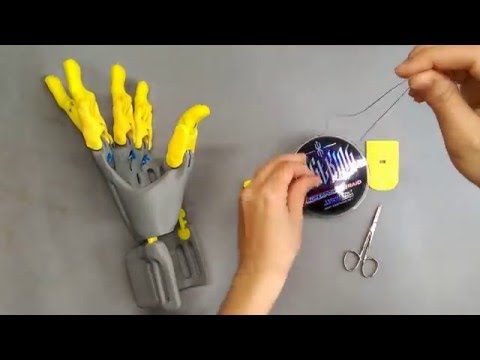

She wanted a tiny version of their hand, but Owen realised the child would rapidly grow out of anything they made, so he looked at the idea of using 3D printing. “If we could develop a design that was printable, it would be possible to rescale and reprint the design as Liam grew, essentially making it possible for his device to grow with him,” he said.

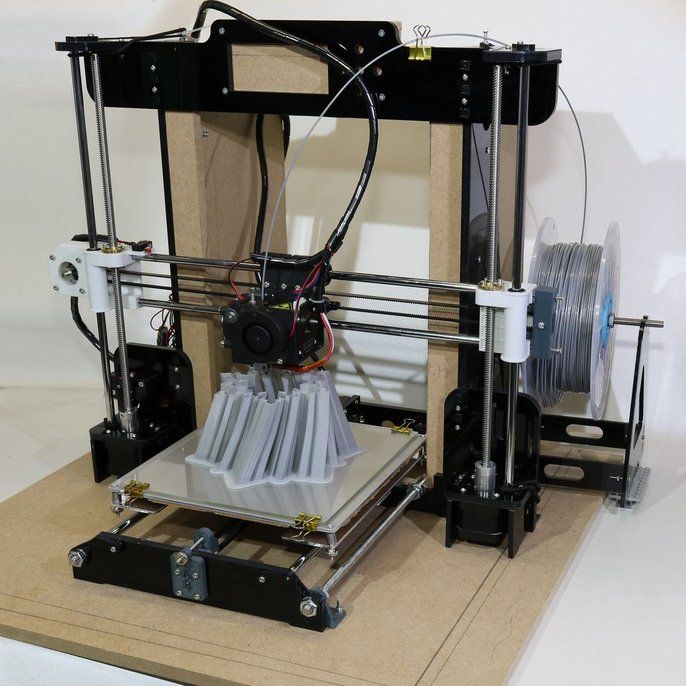

So the artist persuaded a printer manufacturer to donate two machines and developed what has been claimed to be the first 3D-printed mechanical hand. Crucially, rather than patent this work, Owen published the files as open source for anybody to access, allowing others to collaborate on, use and improve the designs.

This has grown into Enabling the Future, a network with 7,000 members in dozens of countries and access to 2,000 printers, who help make arms and hands for those in need. One school student in California even printed a new hand for a local teacher.

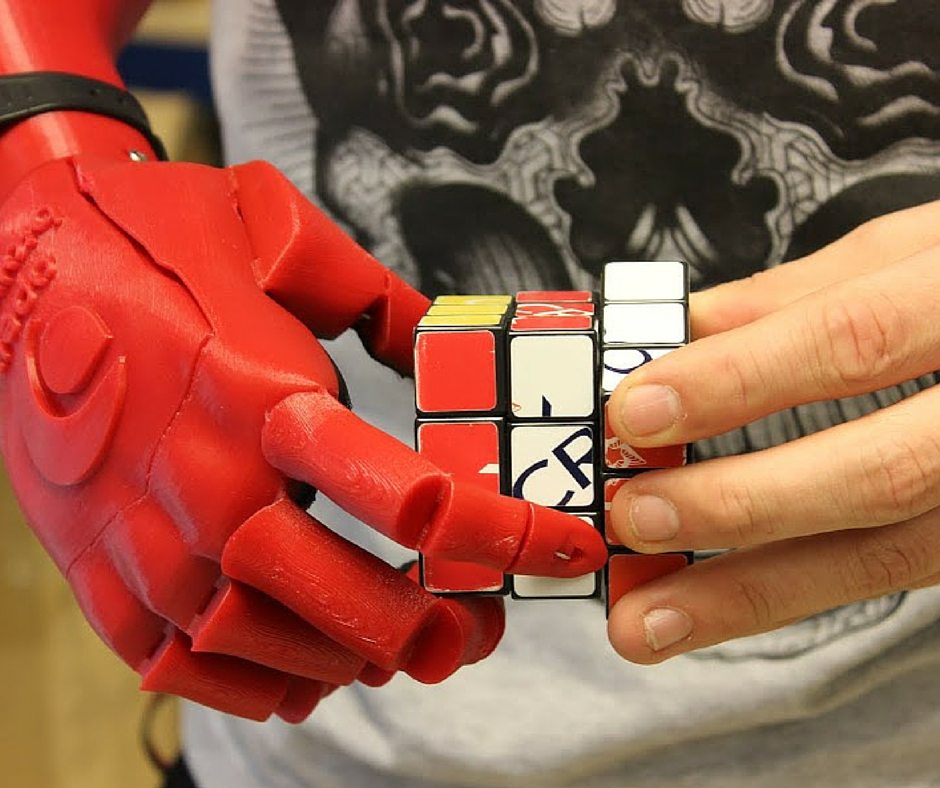

Often they are aimed at children, since many dislike the weight, look and hassle of modern prosthetics, which can involve inserting the arm into a silicone sleeve and using straps across the back to hold the device in place.

These body-powered hands cost thousands of pounds, yet must be replaced every couple of years as a child grows. The 3D-printed versions cost about £40, come in any colour and look like a cheery toy, so are often more appealing despite being less sophisticated.

Jorge Zuniga, a research scientist in the biomechanics research department at the University of Nebraska in Omaha, heard about this project on his car radio. He was only half-listening, but on arriving home he started playing baseball with his four-year-old son and observed how important the grabbing of an object was to his child’s development.

A Cyborg Beast prosthetic hand.He spent the next month carefully building a prosthetic model that mimicked the human hand, only for his work to be dismissed instantly by his son. “He told me children wanted a hand that looked like a robot.”

From this conversation and the open-source designs emerged Cyborg Beast, a project heavily backed by Zuniga’s department to develop futuristic-looking, low-cost prosthetic hands. “You can do anything with 3D printing,” said Zuniga, who now leads a seven-strong team. “We believe it will revolutionise the prosthetics field. It will lower the costs worldwide and gives engineers, patients and doctors the chance to modify prosthetic hands as they want. And they can be any colour.”

“You can do anything with 3D printing,” said Zuniga, who now leads a seven-strong team. “We believe it will revolutionise the prosthetics field. It will lower the costs worldwide and gives engineers, patients and doctors the chance to modify prosthetic hands as they want. And they can be any colour.”

When I told Zuniga, slightly hesitantly, that his design looked like a toy, he was delighted. “That’s great – we want children to see it as a toy,” he said. “This is a transitional device. Many children do not like prosthetics, however good they are these days, because they might have a hook for a hand and they need help to put the harness on, which children dislike. So this is to bridge the gap, helping them get used to the idea as they grow up.”

“We have even had a child missing a shoulder. So we developed a device that weighs the same as the missing arm. This meant he not only got a new arm that helped daily life but it also improved his posture and balance, therefore was much better for his spine. This sort of thing can be done much easier with 3D technology.”

This sort of thing can be done much easier with 3D technology.”

It is remarkable that people who do not even own a printer can obtain a functional child’s hand for the price of a theatre ticket within 24 hours. Zuniga says at least 500 Cyborg Beasts are in use worldwide and the design has been downloaded more than 48,000 times. He has taken it to his native Chile, where he runs a paediatric orthopaedic 3D-printing laboratory, and has had recent requests for the plans from Nigeria.

“My concern at this stage is that some of the materials can melt in higher temperatures. It is not working well there yet, but this sort of prosthetic has huge potential to be used with better materials in the developing world. We are still in the infancy stage at this moment.”

Another scheme experimenting with this technology is Project Daniel in the Nuba mountains of Sudan, where in the middle of the ongoing civil war an American physician, Tom Catena, has been working as the only permanent doctor for half-a-million people around his Mother of Mercy hospital. Fuelled by his religious faith, for almost a decade this brave medic has ignored bombings, a lack of electricity and water shortages to do everything from delivering babies to amputating limbs.

Fuelled by his religious faith, for almost a decade this brave medic has ignored bombings, a lack of electricity and water shortages to do everything from delivering babies to amputating limbs.

“It’s demoralising for us to amputate an arm knowing that there is no good solution,” Catena told me by email. “We have many arm amputees – both above and below the elbow as a result of the war here and general lack of medical care. This in an agricultural society, where nearly everyone is a subsistence farmer. If one is missing an arm, he is not very functional in this society.They become totally dependent on the family and have a difficult time getting married [which is also very important in this society].”

The idea of using 3D printing to help arose when Mick Ebeling, an American film producer and philanthropist, learned about the Mother of Mercy hospital at the same time as he was hearing about the emerging work on low-cost prosthetic hands. Searching for information on Catena, Ebeling read about one of his patients: Daniel Omar, a 12-year-old boy who had wrapped his arms around a tree to protect himself during an aerial attack. His face and body were protected when a bomb exploded nearby, but both the boy’s arms were blown off.

His face and body were protected when a bomb exploded nearby, but both the boy’s arms were blown off.

You can’t just smash in these new technologies, but if we get this right the growth could be exponentialMatt Ratto, Nia Technologies

Ebeling travelled out to the Nuba mountains with 3D printers and, working with hospital staff, fitted about a dozen people with new arms. “Unfortunately, as time went on, none of the amputees was using the prostheses as they felt they were too cumbersome,” said Catena. The doctor concluded: “The 3D model was good, fairly easy to make and inexpensive… although it hasn’t worked out so well here. Perhaps with some tweaking, the 3D printers can be of great use for arm amputees.”

Yet for all the agonies and difficulties associated with arm loss, the bigger problem in poorer countries is when lower limb disability leads to a loss of mobility. Wheelchairs are expensive and can be difficult to use when roads are potholed, streets are muddy and pavements are nonexistent. Without a prosthetic limb, people struggle to fetch water, prepare food and, above all, to work. This throws them back on their families and communities, intensifying any hardship and poverty.

Without a prosthetic limb, people struggle to fetch water, prepare food and, above all, to work. This throws them back on their families and communities, intensifying any hardship and poverty.

One group that has spent almost three decades trying to tackle these issues is Exceed, a British charity set up by diplomats and academics at the request of Cambodia’s government to help thousands of landmine survivors. It works in five Asian countries, training people at schools of prosthetics and orthotics. In Cambodia, there are almost 9,000 landmine survivors in need of artificial limbs, although these days traffic accidents are a more likely cause of disability, while children also need braces for a range of common conditions such as spina bifida, cerebral palsy and polio.

“If you wear a prosthesis, you are disabled for about 10 minutes in the morning while you have a shower, then you put your leg on and go to work. If you do not have one, then your hands are out of use with crutches so you can’t even take drinks to the table,” said Carson Harte, a prosthetist and the chief executive of Exceed. “Without a prosthesis, there are no expectations. You just go back and rely on the goodwill of your family.”

“Without a prosthesis, there are no expectations. You just go back and rely on the goodwill of your family.”

It is not really a lack of money that denies people these devices, since simplified forms cost little and generic Chinese models are improving fast. The components can cost just £30. The big hurdle is the lack of trained technicians to fit the artificial limbs. In the Philippines, there are estimated to be 2 million people needing prosthetics or orthotics. However, there are only nine fully trained experts, each able to treat 400 patients a year, at most, although more are being trained on a new four-year course.

Orthopaedic technician Moses Kaweesa assembles a 3D-printed artificial leg at CoRSU hospital in Uganda. Photograph: Isaac Kasamani/AFP/Getty ImagesTraditionally, a prosthetist would wrap a stump with plaster of Paris bandages to make a reverse mould and let it dry, then fill it with more plaster that must harden. From this, a socket can be forged that fits, with more modifications for precision, to the bone on the stump. Great care must be taken to avoid nerves and tender areas that are not tolerant of pressure.

Great care must be taken to avoid nerves and tender areas that are not tolerant of pressure.

The key for the technician is to understand the pathology of a stump, which differs for each person. This is a cumbersome process that can take a week, especially with physical therapy for new patients that lasts three days. It can also be messy work, mixing up and moulding the plaster, while a prosthetist visiting a rural area must transport 20-kilo packs of plaster. With a 3D scanner, a digital image can be made in half an hour and sent by email.

Exceed has begun a seven-month trial of 3D-printed devices in Cambodia with Nia Technologies, an innovative Canadian not-for-profit organisation. “This technology has the potential to increase the productivity of every technician,” said Harte. “It is not about printing off legs, nor does it replace the skills of a well-trained professional, but it has potential to produce a better, faster, more easily repeatable way of doing one key part of the chain. There are no magic bullets, but this may be an important incremental change.”

There are no magic bullets, but this may be an important incremental change.”

Nia is also trialling its 3D PrintAbility technology in Tanzania and Uganda, where there are only 12 prosthetists to serve a population of about 40 million people; at the time of writing, all six state clinics have run out of materials. Doctors there often deal with children who have lost limbs after falling into open cooking fires, while other youngsters need braces after suffering post-injection paralysis caused by badly administered jabs that damage nerves.

In Uganda, its team is working with CoRSU hospital in Kisubi, a specialist rehabilitation centre for children with disabilities. Orthopaedic technician Moses Kaweesa said they found the technology lighter and faster to use, as well as easier for people in remote rural areas. “It used to take five days to have a limb manufactured, with lots of hanging around for the patient. Now, it is barely two days, so they spend much less time in the hospital. There is also less waste of material, so for a country like ours this can help so much by cutting down the costs.”

There is also less waste of material, so for a country like ours this can help so much by cutting down the costs.”

The first person to test out a 3D-printed mobility device at the hospital was a four-year-old girl who until then had dragged herself across floors and had to be carried around by her family. “When she was born, her right leg was missing the foot,” said her older brother. “It was very difficult for her to walk, to play with other children. She can be lonely. But when she was given a leg she was able to run with others, play with others.”

Matt Ratto, Nia’s chief science officer, who led the project’s development, admitted that it was only when he saw the serious-looking child in her red dress start to walk that he realised his technology actually worked. But, like Harte, he urges caution. “We are surrounded by the hype of 3D printing with crazy, ridiculous claims being made,” he said. “We must be cautious. A lot of these technologies fail not for engineering reasons but because they are not designed for the developing world. You can’t just smash in these new technologies.”

A lot of these technologies fail not for engineering reasons but because they are not designed for the developing world. You can’t just smash in these new technologies.”

Ratto’s aim is to use the technology to fit 8,000 people with 3D-printed mobility devices within five years, across some 20 sites in poorer countries. “If we get this right the growth could be exponential. If we iron out the kinks, and work out the best way to help clinicians, I think we will see something of a hockey stick curve on the graph. But we must not get it wrong, move too fast nor over-hype the potential.”

This article first appeared on Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence

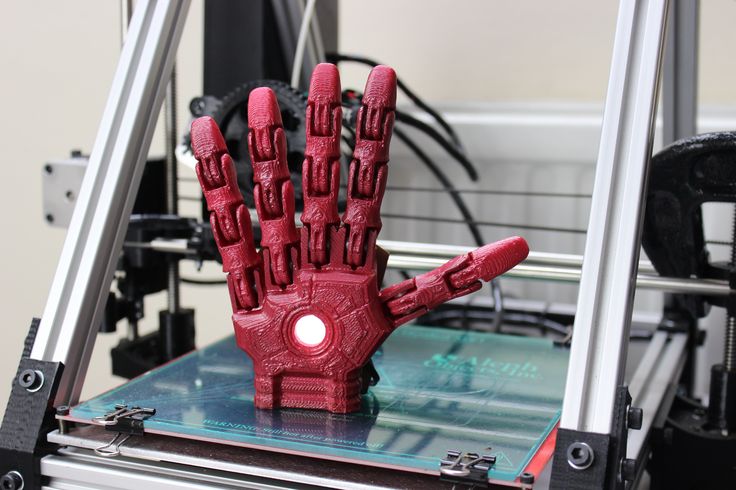

Top Examples of 3D Printed Prostheses

Published on April 7, 2022 by Niru K.

When it comes to industries adopting 3D printing, one of the earliest and most fervent supporters of the technologies is of course the medical sector. Indeed, AM is becoming a crucial tool in healthcare thanks to a variety of factors. This is especially the case when it comes to prosthetics. With 3D printing, the benefits are two-fold. First, of course, the prostheses can be perfectly fit to the patient thanks to the ability to customize the part. But additionally, 3D printing enables lower-cost, local production of prostheses. As the World Health Organization estimates that 30 million people worldwide are in need of prosthetics, this can help increase availability for many especially in remote regions. We took a look at some of the top examples of 3D printed prosthetics currently available.

This is especially the case when it comes to prosthetics. With 3D printing, the benefits are two-fold. First, of course, the prostheses can be perfectly fit to the patient thanks to the ability to customize the part. But additionally, 3D printing enables lower-cost, local production of prostheses. As the World Health Organization estimates that 30 million people worldwide are in need of prosthetics, this can help increase availability for many especially in remote regions. We took a look at some of the top examples of 3D printed prosthetics currently available.

The E-nable association

E-nable, also known as Enabling the future , is an association created in the United States by Jen Owen. The idea behind this project is to bring together makers and enthusiasts to create a network of models of prostheses in the world that can obviously be printed in 3D. The main objective is to “give a hand” to the people who need it most, thus avoiding the high cost of a traditional prosthesis. Since its creation in 2013, the association has donated 3D printed prostheses to hundreds of people around the world.

Since its creation in 2013, the association has donated 3D printed prostheses to hundreds of people around the world.

Bionico Hand, an Open-Source 3D Printed Prosthesis

The Bionico Hand project is the brainchild of Frenchman Nicolas Huchet who has used a bionic hand since he was 18 years old. After making his own, he launched Bionicohand as a way to make more for himself and others. Essentially, what he has conceived is a myoprosthesis, his own term for a myoelectric prosthetic, that can repair itself. He aims to create something designed by and for amputees that will be available open source so anyone can make their own. The project is not yet ready, though it has been in development for a number of years now. However, the proof of concept was produced in October 2021 and the goal is to transform it into a functional prototype by the end of 2022.

Photo Credits: Bionico Hand

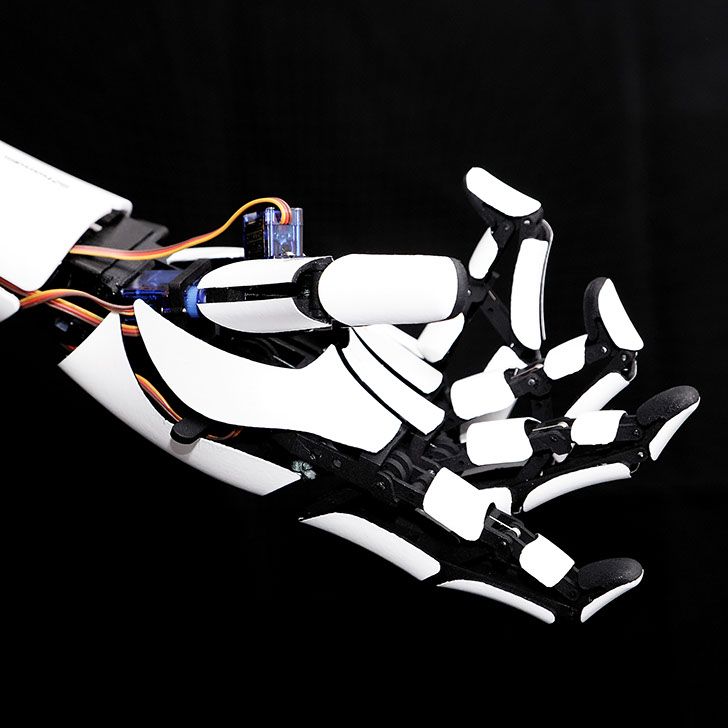

Make Your Own 3D Printed Robotic Arm with Youbionic

Created by Federico Ciccarese, Youbionic is a platform that is a little different from many on our list. It is not technically designed to create prosthetics for those in need, but rather a way for young people to enter into the robotics industry. Essentially, buyers will receive a kit with everything they need to create their very own robotic arms, including 3D printing part files. These files have been designed to be easy to print as well as oriented to obtain the best results. And best of all? There are not many parts that make up an Avatar Full Arm (one of the largest available projects), leaving users will less assembly than they might expect. On the company’s website, they have a variety of cool projects that you can buy, including full arms, hands, double hands and more.

It is not technically designed to create prosthetics for those in need, but rather a way for young people to enter into the robotics industry. Essentially, buyers will receive a kit with everything they need to create their very own robotic arms, including 3D printing part files. These files have been designed to be easy to print as well as oriented to obtain the best results. And best of all? There are not many parts that make up an Avatar Full Arm (one of the largest available projects), leaving users will less assembly than they might expect. On the company’s website, they have a variety of cool projects that you can buy, including full arms, hands, double hands and more.

Photo Credits: Youbionic

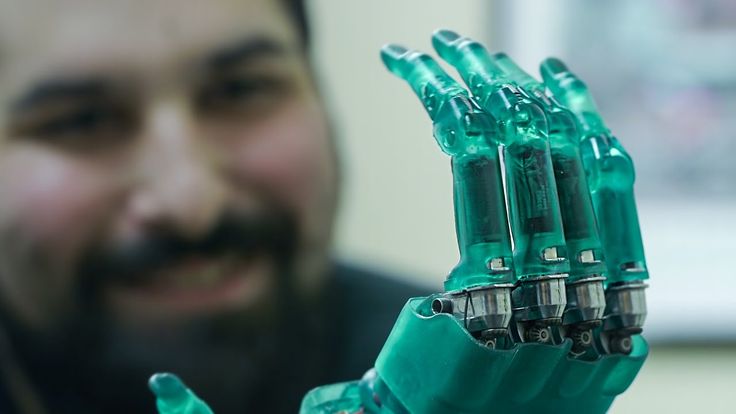

Unlimited Tomorrow – The Name Says it All

Unlimited Tomorrow was founded in Colorado in 2011 by Easton LaChapelle who had been working on robotic limb development for a few years. However, she decided to launch into this project after meeting a little girl who wore a prosthetic limb that had limited capabilities while still being expensive. Thus, the idea of Unlimited Tomorrow and improved prosthetics was born. It aims to support people with upper limb disabilities by using additive manufacturing to produce high quality, high value, low cost bionic prosthetic arms. 3D printing allows for the process to be customizable. This happens as after the user answers a few questions, they are then sent a 3D scanner to scan the residual limb. Based on this, the prosthesis, which can also be personalized, is produced with the 3D printer.

Thus, the idea of Unlimited Tomorrow and improved prosthetics was born. It aims to support people with upper limb disabilities by using additive manufacturing to produce high quality, high value, low cost bionic prosthetic arms. 3D printing allows for the process to be customizable. This happens as after the user answers a few questions, they are then sent a 3D scanner to scan the residual limb. Based on this, the prosthesis, which can also be personalized, is produced with the 3D printer.

Photo Credits: Unlimited Tomorrow

A Distinct Prosthesis with UNYQ

3D printing is used at UNYQ to use mass production to create innovative, customized prostheses. In addition to being able to develop next-generation products, additive manufacturing is also used for aesthetically pleasing and practical features. Prostheses for above and below the knee amputees offer patients revolutionary personalization in terms of color and design. Currently, they are even working on manufacturing an entire leg. UNYQ provides its patients with an app to create the 3D-printed prostheses: Color, design and surface can be selected, then measurements are taken in a clinic to finally print the prosthesis using additive manufacturing.

UNYQ provides its patients with an app to create the 3D-printed prostheses: Color, design and surface can be selected, then measurements are taken in a clinic to finally print the prosthesis using additive manufacturing.

3D Printed Foot Prostheses from Mercuris

Mecuris is a German company dedicated to the development of CAD/CAM software solutions that, together with 3D printing, make it possible to create foot prostheses. Thanks to a digital platform, called Mecuris Solution Platform, users can create and customize their individual models to their liking, saving time and money. In fact, thanks to 3D technology and its flexibility, the company is able to reduce production costs by 75%. With this, Mecuris’ goal is to convert traditional craftsmanship into digital tools and workflows that are easy to use according to the needs of each individual, and accompanying customers in every step of the process.

LimbForge Offers Prostheses in Remote Regions

LimbForge, a US-based non-profit organization, works on creating software, design and innovative manufacturing with 3D scanning and 3D printing. With these tools they are able to develop and deliver high quality and affordable custom prosthetics. LimbForge has developed and implemented a platform that allows clinicians to spend less time customizing devices and more time treating a greater number of patients. Its platform provides more realistic designs that help patients integrate and thrive, reduces costs and also offers ultralight prosthetics. The Limbforge platform can be used to size and implement other designs beyond its existing catalog. In fact, once a prosthetic design is in the database, it can be easily configured to fit almost any human anatomy. Notably, the platform is being used to help amputees in developing countries to gain access to high quality prostheses.

With these tools they are able to develop and deliver high quality and affordable custom prosthetics. LimbForge has developed and implemented a platform that allows clinicians to spend less time customizing devices and more time treating a greater number of patients. Its platform provides more realistic designs that help patients integrate and thrive, reduces costs and also offers ultralight prosthetics. The Limbforge platform can be used to size and implement other designs beyond its existing catalog. In fact, once a prosthetic design is in the database, it can be easily configured to fit almost any human anatomy. Notably, the platform is being used to help amputees in developing countries to gain access to high quality prostheses.

Photo Credits: Limbforge

3D Printing the Prostheses of the Future

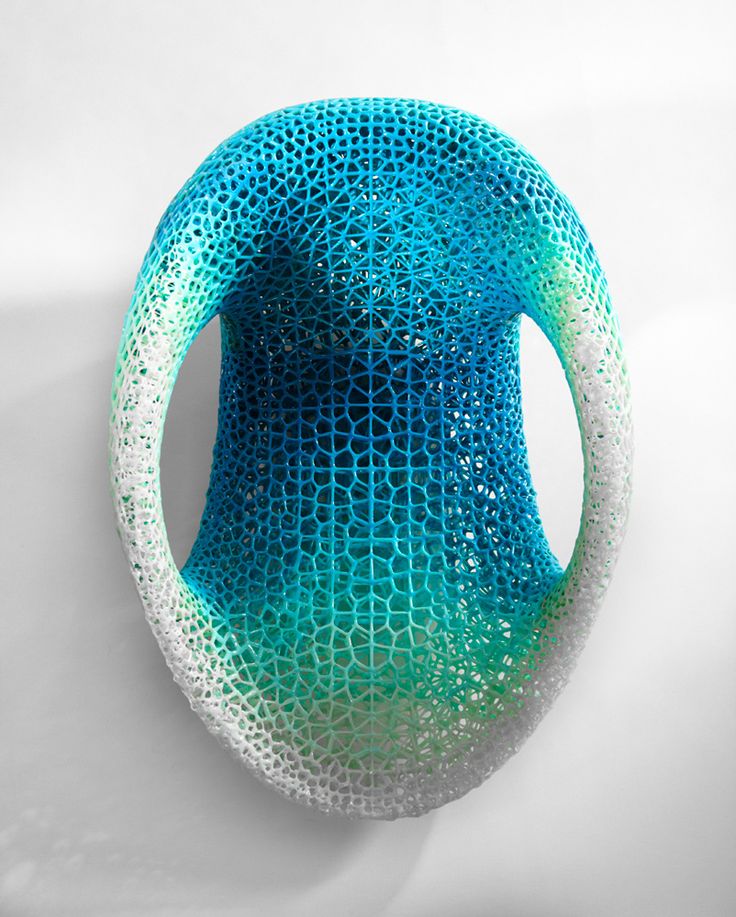

Evan Kuester is an engineer, artist and designer currently working as a Senior Advanced Applications Engineer at 3D Systems. In addition to that, Kuester is pursuing a number of interesting projects using additive manufacturing. Among them is the development of prosthetics with extremely modern and futuristic designs. For example, in the photo below we see the JD-2 prosthesis model, created with the intention of further exploring the possibilities available to designers with SLS 3D printing technology. Its inner mesh-like structure is intended to reduce the weight of the prosthesis as well as to achieve a more pleasing aesthetic.

Among them is the development of prosthetics with extremely modern and futuristic designs. For example, in the photo below we see the JD-2 prosthesis model, created with the intention of further exploring the possibilities available to designers with SLS 3D printing technology. Its inner mesh-like structure is intended to reduce the weight of the prosthesis as well as to achieve a more pleasing aesthetic.

“Hero Arm”, a Hero for Life

Open Bionics was the first company in the world to launch a 3D printed bionic arm that would not only be clinically tested but also medically certified. This 3D printed arm is called “Hero Arm” and combines functionality, comfort and design. It is customizable and includes sensors to detect muscle movements, thus providing more ease to move. It would even be able to lift up to 8 kilos, a rather high weight when we know that the prosthesis is put and removed quickly. Open Bionics offers complete customisation of the prosthesis, a real advantage for the person who wears it, who can then create it in his own image. A particularly attractive point for children who often choose a prosthesis with the image of their hero!

A particularly attractive point for children who often choose a prosthesis with the image of their hero!

3D Prostheses for the Needy

In Africa, many countries have a healthcare system that is unable to treat injuries caused by traffic accidents or infections, so it continues to experience a large number of amputations. That is why there are several non-profit organizations that want to bring printing technologies to anyone in need and anywhere in the world. One example is Ayúdame 3D, a Spanish organization that promotes the social value of technology through technological-social awareness programs in order to help vulnerable groups around the world. Both it and 3D Sierra Leone create 3D printed arms, free of charge, for people with disabilities. Thanks to this, they manage to improve their quality of life and that of their environment, reduce the inequality they face and provide them with greater opportunities for schooling and employability.

Naked Prosthetics and Resin 3D Printing

Based in the United States, Naked Prosthetics (NP) is a company dedicated to the development of functional prosthetic devices for hands and fingers. To do so, they rely on resin 3D printing, specifically stereolithography, with which they create these customized models adapted to the needs of each user. Thanks to 3D printing, Naked Prosthetics is able to deliver the prosthetic devices within a few weeks. As they state on their website, NP’s mission is to help people with partial amputation of fingers and hands, to change their lives positively through functional and high quality prostheses.

To do so, they rely on resin 3D printing, specifically stereolithography, with which they create these customized models adapted to the needs of each user. Thanks to 3D printing, Naked Prosthetics is able to deliver the prosthetic devices within a few weeks. As they state on their website, NP’s mission is to help people with partial amputation of fingers and hands, to change their lives positively through functional and high quality prostheses.

Photo Credits: Naked Prosthetics

A Fully 3D Printed Ocular Prosthesis

We recently learned of the UK case of Steve Verze, a Londoner, who became the first person in the world to receive a fully 3D printed ocular prosthesis. The printed prosthesis is part of a collaboration between several players in the UK and Europe, and was led by researchers at UCL and Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The result? A prosthetic eye is impressively realistic thanks to its clearer definition and lifelike depth which was made possible with eye socket scans to ensure a good match.

Lattice Medical, Fighting Breast Cancer with 3D Printing

Taking on breast cancer – that’s what Lattice MEdical, a company founded in Lille, aims to do. Founded in 2017, the company has produced a bioprosthesis called MATTISSE, which could offer an alternative to the silicone prostheses commonly used to help treat breast cancer patients. The silicone prostheses commonly used have to be replaced about every 10 years for safety reasons, which is why the MATTISSE bioprosthesis is made of an absorbable material that can be optimally adapted to the patient’s morphology thanks to the use of additive manufacturing. Lattice Medical uses FDM technology to be able to create the natural reconstruction as they regenerate the patient’s own fatty tissue.

Photo Credits: Lattice Medical

What do you think of these 3D printed prostheses? Let us know in a comment below or on our Facebook and Twitter pages! Sign up for our free weekly Newsletter, all the latest news in 3D printing straight to your inbox!

3D printed bionic prostheses from Unlimited Tomorrow

You are here

Home

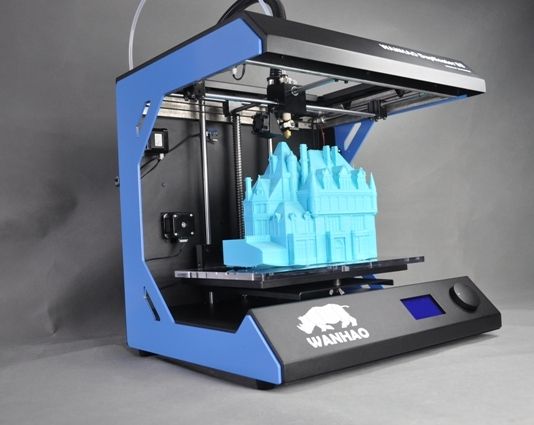

The American company Unlimited Tomorrow brought to the market 3D printed bionic prosthetic hands with a custom design. Artificial hands with six grips are created from individual 3D scans of patients and are offered for eight thousand dollars.

Artificial hands with six grips are created from individual 3D scans of patients and are offered for eight thousand dollars.

Unlimited Tomorrow is the brainchild of a young entrepreneur named Easton LaChapelle, who built his first remote-controlled robotic arm at the age of fourteen. Three years later, the now high school student was invited to the traditional school science fair at the White House after winning a competition at the Intel International Science and Technology Fair, and another year later, Easton joined forces with British designer and almost namesake Christopher Chappelle and launched his own startup, collecting the initial funding on the Kickstarter crowdfunding site.

Easton is now twenty-four years old and leads a company that offers a ready-made commercial product - functional 3D printed prostheses. The idea of a startup was born back in his school years, when during one of the fairs, his attention was attracted by a girl who was carefully studying his booth with a robot. The girl was missing her right arm, and a rather simple electromechanical prosthesis with one grip replaced the limb. As it turned out, this miracle of technology cost parents eighty thousand dollars.

The girl was missing her right arm, and a rather simple electromechanical prosthesis with one grip replaced the limb. As it turned out, this miracle of technology cost parents eighty thousand dollars.

TrueLimb prostheses can hardly be called cheap either, but they are much more affordable in terms of affordability: Unlimited Tomorrow offers its products for $7,995 or in installments with monthly payments of $259, working directly with patients, without intermediaries, while the closest analogues cost about twenty thousand even with good health insurance. In addition, these hands are much more functional, being able to perform six different grips with individual finger control, and much more attractive to look at than many of the analogues.

The hand size, color and detailing is chosen by the future user, who only needs to go through the 3D scanning procedure. Scanning can be performed at home: the company sends the necessary equipment and instructions to selected candidates. Then the company's engineers bring the 3D scans up to standard and use the resulting digital models to print components on a color 3D printer from Hewlett Packard using Multi Jet Fusion technology. The minimum age of a candidate for prosthetics is seven years.

Then the company's engineers bring the 3D scans up to standard and use the resulting digital models to print components on a color 3D printer from Hewlett Packard using Multi Jet Fusion technology. The minimum age of a candidate for prosthetics is seven years.

For now, the company is focusing on prosthetic arms, but is considering making artificial lower limbs and even exoskeletons. The most well-known Russian manufacturer of custom prostheses using 3D printing technologies is the Moscow company Motorika, which offers low-cost mechanical traction prostheses "Kibi", myoelectric prostheses "Indy" with one grip, and also working on bionic artificial hands "Manifesto" with fourteen grips. . Customers can count on compensation through the Social Security Fund. This summer, Motorika received the CE marking for all its products and announced its intention to enter the European market.

CNET edition of the Unlimited Tomorrow project:

Source

Tags:

TrueLimb prostheses, 3D printed bionic prostheses from Unlimited Tomorrow, Multitard 3D printed technology Jet Fusion, 3D scanning, 3D printing technologies, Motorika

Other materials:

- 3D Scanning FAQ Part 2

- Digital artisans. Where will our children work?

- Food from a printer: who uses 3D printing in cooking and why

- The scope of Werth tomographs and their capabilities

- Computer simulation of metal 3D printing processes based on MSC Software solutions

Attention!

We accept news, articles or press releases

with links and images. [email protected]

Printing prostheses on a 3D printer, the use of 3D technologies in prosthetics | project news 3DPulse.Ru

Printing prostheses on a 3D printer, the use of 3D technologies in prosthetics | project news 3DPulse. Ru - page 3

Ru - page 3 3d pulse.ru

Our new report "Construction 3D printing in Russia" has been published

Our report "Construction 3D printing in Russia" has collected information about domestic companies and start-ups that produce...

Vladimir Viktorovich Molodin (SIBSTRIN): "The idea [of printing with polystyrene concrete] appeared three years ago, and it took 30 years to get there."

Interest in 3D construction printing is growing rapidly around the world, with most of the developed 3D printers working with...

Mass 3D printing of individual houses: reality or utopia? - public study by the Techart group

In its public survey, Techart explores whether 3D printing can bring something really new to the construction...

Victor Mann (RUSAL): "In Russia, additive manufacturing is one of the fastest growing industries"

RUSAL is a leading company in the global aluminum industry and the largest aluminum producer with a low carbon footprint. Her...

Her...

"3D Printing in the Oil and Gas Industry: Incentives and Constraints" - Techart Group Public Study

Techart Consulting Group published a study analyzing the current state and development prospects...

Current news

Prostheses

3D printed piano prosthesis

A short story about how 3D printing helped a man realize his dream.

Prostheses

3D-printed middle ear prostheses help treat hearing loss

Hearing in healthy people works by transmitting vibrations from the eardrum to the cochlea through three small auditory...

Prostheses

LimbForge improves 3D-printed prosthetic hand

The LimbForge team, a spin-off from the e-NABLE prosthetic 3D printing community, has developed a 3D-printed prosthetic hand from...

Prostheses

An engineer from Novgorod uses 3D printing to work on a prototype bionic prosthesis.

Novgorod engineer Stanislav Muraviev is working on a new bionic prosthesis. In his work, the developer uses ...

3

Prostheses

3D printed Third Thumb expands human capabilities

Dani Claude, a student at the Royal College of Art in London, has 3D printed an extra large prosthetic...

Prostheses

A software system for the neurocontrol of prostheses is being created in Tomsk

Specialists from the Tomsk University of Control Systems and Radioelectronics (TUSUR) are developing software for...

Prostheses

Samara State Medical University scientists print individual prostheses on a 3D printer

Samara State Medical University scientists have patented a method for manufacturing individual prostheses with...

Prostheses

3D printing makes it possible to create a prosthetic leg for a disabled parrot

Pete, a 34-year-old parrot, lost his leg after being attacked by a fox - thanks to veterinarian Jonathan Wood from.