3D printing making

The Free Beginner's Guide - 3D Printing Industry

Welcome to 3DPI”s Beginner’s Guide to 3D Printing. Whether you are new to 3D printing technology or just looking to close a few knowledge gaps, we’re glad you stopped by. By now, most of us have heard, at some level, about the potential of 3D printing. But with this guide we are offering insights into the history and the reality of 3D printing — the processes, materials and applications — as well as measured thoughts on where it might be heading. We hope you’ll find this to be one of the most comprehensive 3D printing resources available, and that no matter what your skill level is, there will be plenty in here to meet your needs.

Are you ready? Let’s get started !

01 - Basics

3D Printing — also known as additive manufacturing — has been quoted in the Financial Times and by other sources as potentially being larger than the Internet. Some believe this is true. Many others urge that this is part of the extraordinary hype that exists around this very exciting technology area. So what really is 3D printing, who generally uses 3D printers and what for ?

Overview

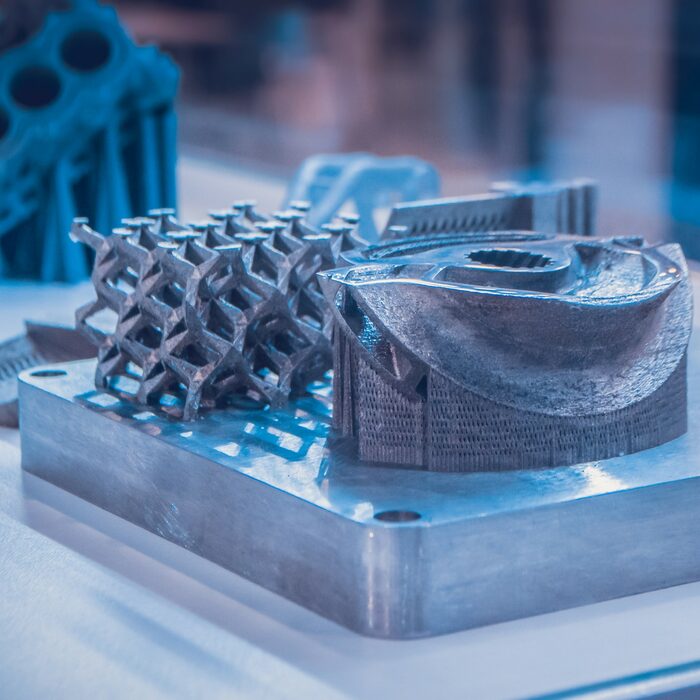

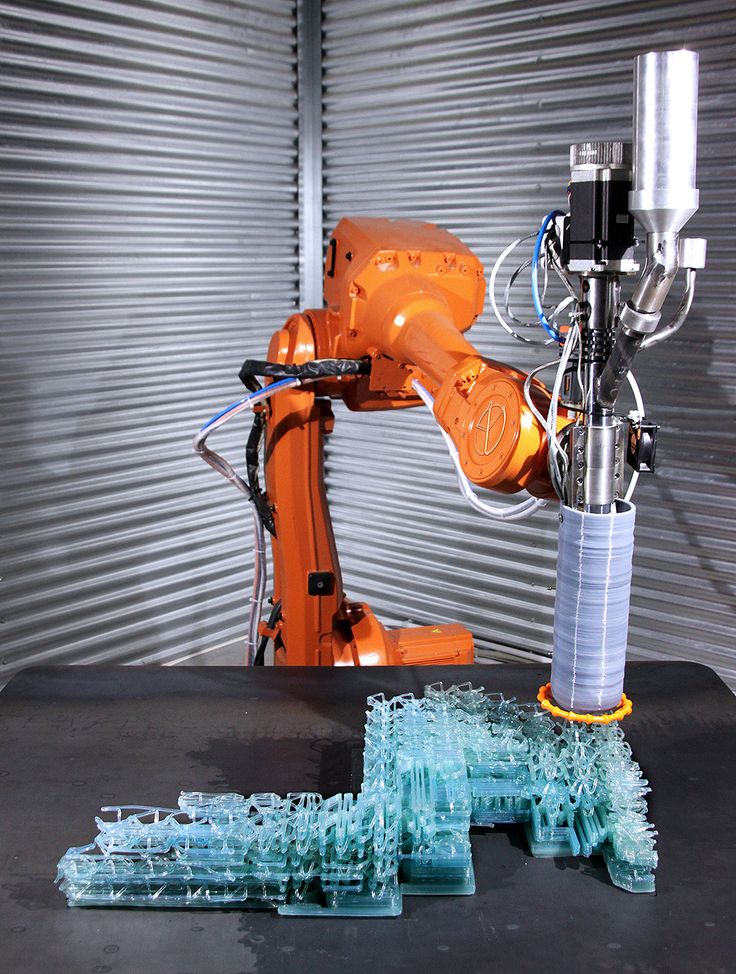

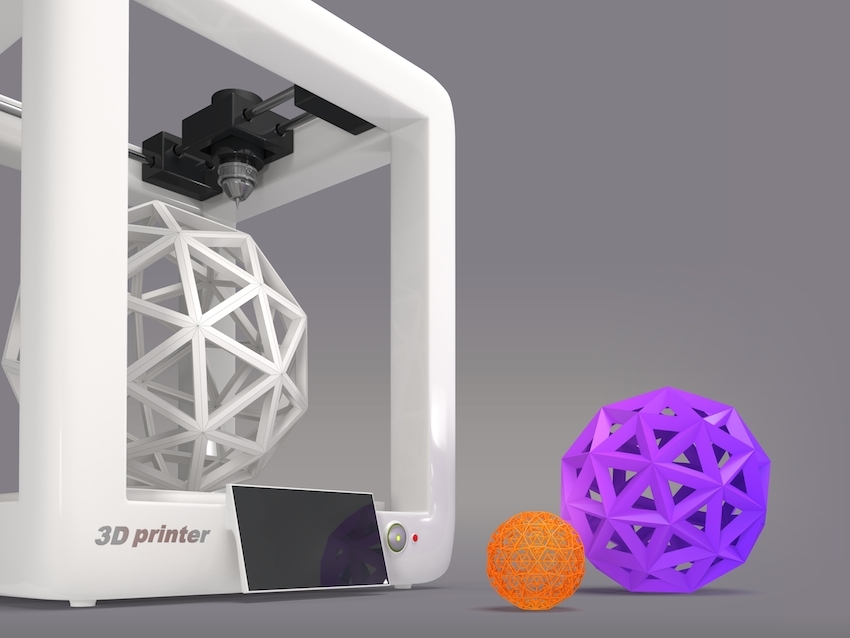

The term 3D printing covers a host of processes and technologies that offer a full spectrum of capabilities for the production of parts and products in different materials. Essentially, what all of the processes and technologies have in common is the manner in which production is carried out layer by layer in an additive process which is in contrast to traditional methods of production involving subtractive methods or moulding/casting processes. Applications of 3D printing are emerging almost by the day, and, as this technology continues to penetrate more widely and deeply across industrial, maker and consumer sectors, this is only set to increase. Most reputable commentators on this technology sector agree that, as of today, we are only just beginning to see the true potential of 3D printing. 3DPI, a reliable media source for 3D printing, brings you all of the latest news, views, process developments and applications as they emerge in this exciting field. This overview article aims to provide the 3DPI audience with a reliable backgrounder on 3D printing in terms of what it is (technologies, processes and materials), its history, application areas and benefits

3DPI, a reliable media source for 3D printing, brings you all of the latest news, views, process developments and applications as they emerge in this exciting field. This overview article aims to provide the 3DPI audience with a reliable backgrounder on 3D printing in terms of what it is (technologies, processes and materials), its history, application areas and benefits

Introduction – What is 3D printing ?

3D Printing is a process for making a physical object from a three-dimensional digital model, typically by laying down many successive thin layers of a material. It brings a digital object (its CAD representation) into its physical form by adding layer by layer of materials.

There are several different techniques to 3D Print an object. We will go in further details later in the Guide. 3D Printing brings two fundamental innovations: the manipulation of objects in their digital format and the manufacturing of new shapes by addition of material.

Digital

+

Additive Manufacturing

Technology has affected recent human history probably more than any other field. Think of a light bulb, steam engine or, more latterly, cars and aeroplanes, not to mention the rise and rise of the world wide web. These technologies have made our lives better in many ways, opened up new avenues and possibilities, but usually it takes time, sometimes even decades, before the truly disruptive nature of the technology becomes apparent.

It is widely believed that 3D printing or additive manufacturing (AM) has the vast potential to become one of these technologies. 3D printing has now been covered across many television channels, in mainstream newspapers and across online resources. What really is this 3D printing that some have claimed will put an end to traditional manufacturing as we know it, revolutionize design and impose geopolitical, economic, social, demographic, environmental and security implications to our every day lives?

The most basic, differentiating principle behind 3D printing is that it is an additive manufacturing process. And this is indeed the key because 3D printing is a radically different manufacturing method based on advanced technology that builds up parts, additively, in layers at the sub mm scale. This is fundamentally different from any other existing traditional manufacturing techniques.

And this is indeed the key because 3D printing is a radically different manufacturing method based on advanced technology that builds up parts, additively, in layers at the sub mm scale. This is fundamentally different from any other existing traditional manufacturing techniques.

There are a number of limitations to traditional manufacturing, which has widely been based on human labour and made by hand ideology rooting back to the etymological origins of the French word for manufacturing itself. However, the world of manufacturing has changed, and automated processes such as machining, casting, forming and moulding are all (relatively) new, complex processes that require machines, computers and robot technology.

However, these technologies all demand subtracting material from a larger block whether to achieve the end product itself or to produce a tool for casting or moulding processes and this is a serious limitation within the overall manufacturing process.

For many applications traditional design and production processes impose a number of unacceptable constraints, including the expensive tooling as mentioned above, fixtures, and the need for assembly for complex parts. In addition, the subtractive manufacturing processes, such as machining, can result in up to 90% of the original block of material being wasted. In contrast, 3D printing is a process for creating objects directly, by adding material layer by layer in a variety of ways, depending on the technology used. Simplifying the ideology behind 3D printing, for anyone that is still trying to understand the concept (and there are many), it could be likened to the process of building something with Lego blocks automatically.

In addition, the subtractive manufacturing processes, such as machining, can result in up to 90% of the original block of material being wasted. In contrast, 3D printing is a process for creating objects directly, by adding material layer by layer in a variety of ways, depending on the technology used. Simplifying the ideology behind 3D printing, for anyone that is still trying to understand the concept (and there are many), it could be likened to the process of building something with Lego blocks automatically.

3D printing is an enabling technology that encourages and drives innovation with unprecedented design freedom while being a tool-less process that reduces prohibitive costs and lead times. Components can be designed specifically to avoid assembly requirements with intricate geometry and complex features created at no extra cost. 3D printing is also emerging as an energy-efficient technology that can provide environmental efficiencies in terms of both the manufacturing process itself, utilising up to 90% of standard materials, and throughout the products operating life, through lighter and stronger design.

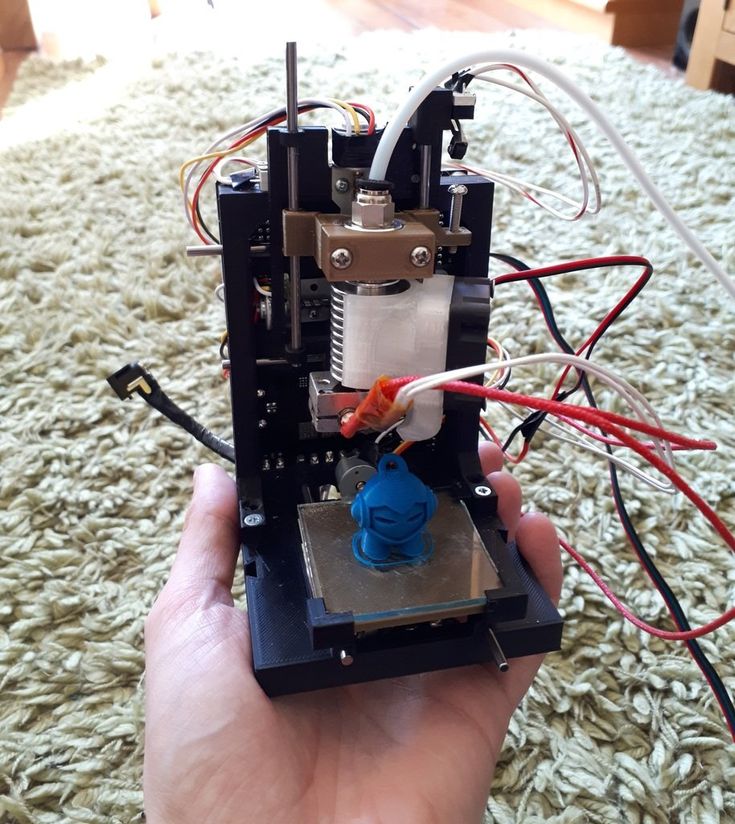

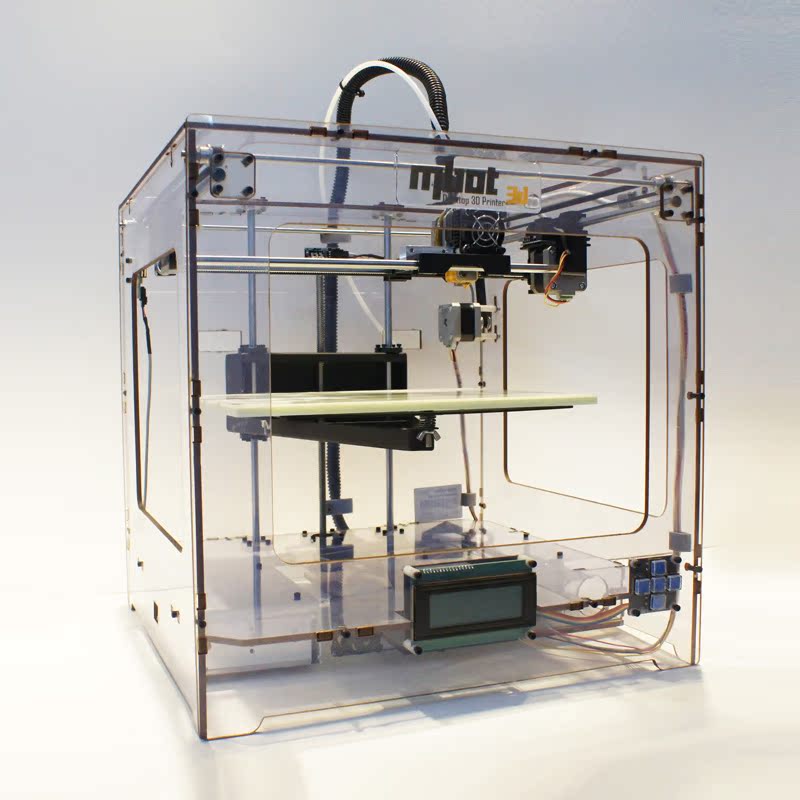

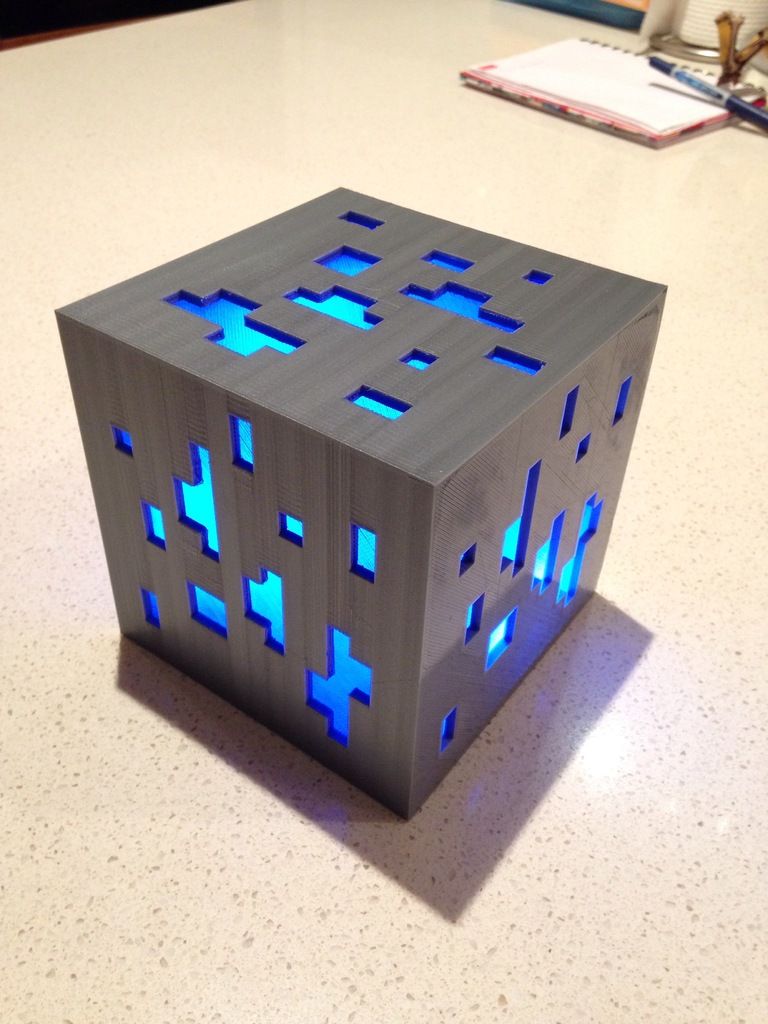

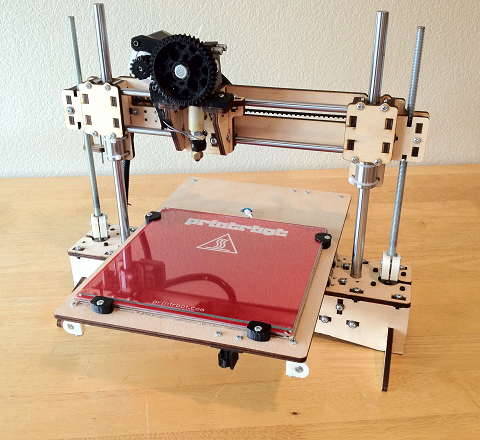

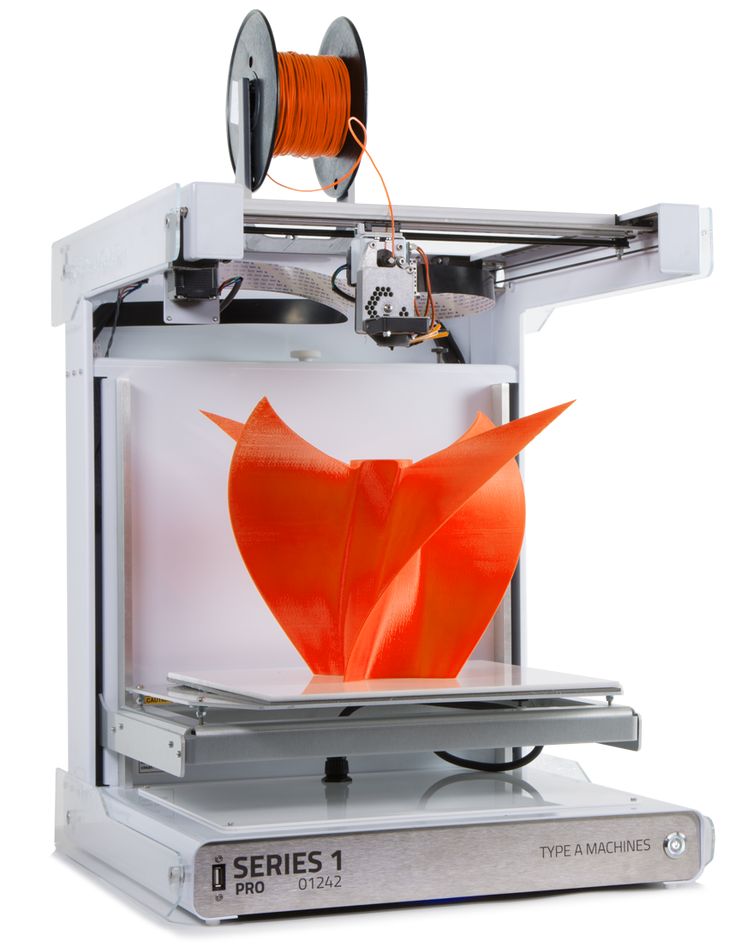

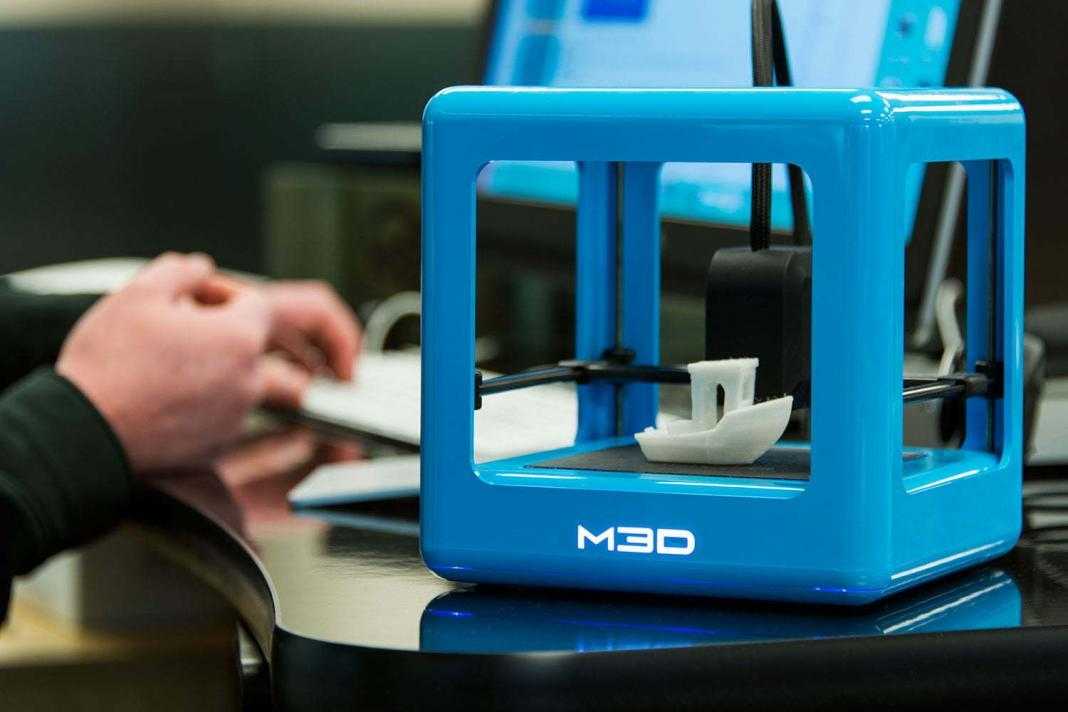

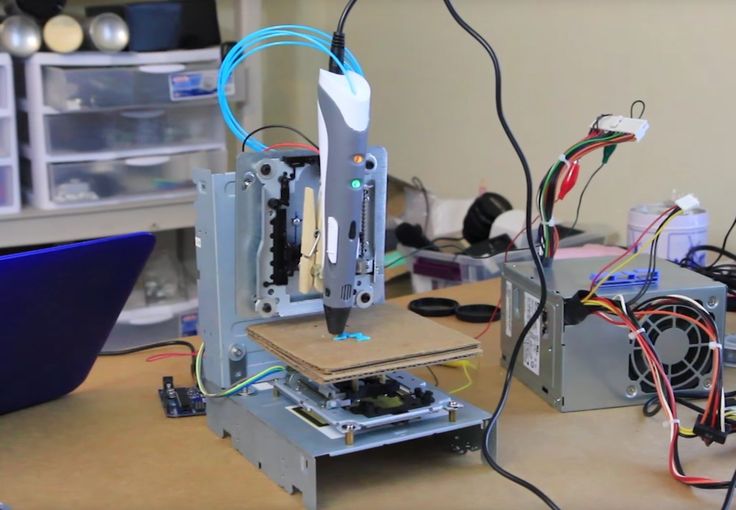

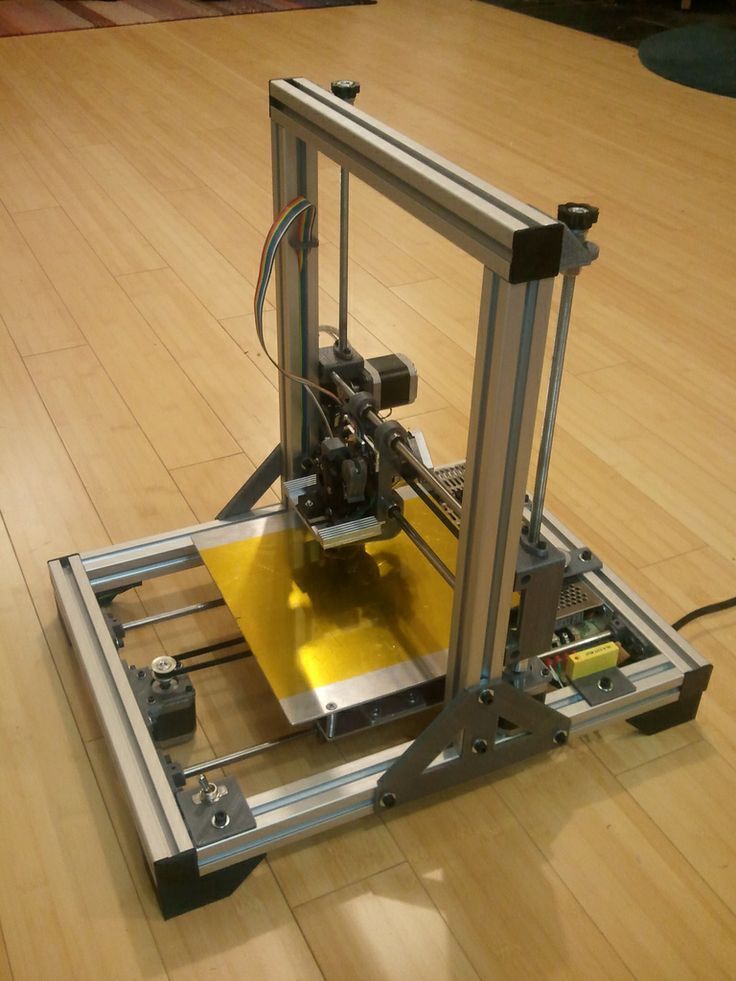

In recent years, 3D printing has gone beyond being an industrial prototyping and manufacturing process as the technology has become more accessible to small companies and even individuals. Once the domain of huge, multi-national corporations due to the scale and economics of owning a 3D printer, smaller (less capable) 3D printers can now be acquired for under $1000.

This has opened up the technology to a much wider audience, and as the exponential adoption rate continues apace on all fronts, more and more systems, materials, applications, services and ancillaries are emerging.

02 - History

The earliest 3D printing technologies first became visible in the late 1980’s, at which time they were called Rapid Prototyping (RP) technologies. This is because the processes were originally conceived as a fast and more cost-effective method for creating prototypes for product development within industry. As an interesting aside, the very first patent application for RP technology was filed by a Dr Kodama, in Japan, in May 1980. Unfortunately for Dr Kodama, the full patent specification was subsequently not filed before the one year deadline after the application, which is particularly disastrous considering that he was a patent lawyer! In real terms, however, the origins of 3D printing can be traced back to 1986, when the first patent was issued for stereolithography apparatus (SLA). This patent belonged to one Charles (Chuck) Hull, who first invented his SLA machine in 1983. Hull went on to co-found 3D Systems Corporation — one of the largest and most prolific organizations operating in the 3D printing sector today.

Unfortunately for Dr Kodama, the full patent specification was subsequently not filed before the one year deadline after the application, which is particularly disastrous considering that he was a patent lawyer! In real terms, however, the origins of 3D printing can be traced back to 1986, when the first patent was issued for stereolithography apparatus (SLA). This patent belonged to one Charles (Chuck) Hull, who first invented his SLA machine in 1983. Hull went on to co-found 3D Systems Corporation — one of the largest and most prolific organizations operating in the 3D printing sector today.

3D Systems’ first commercial RP system, the SLA-1, was introduced in 1987 and following rigorous testing the first of these system was sold in 1988. As is fairly typical with new technology, while SLA can claim to be the first past the starting post, it was not the only RP technology in development at this time, for, in 1987, Carl Deckard, who was working at the University of Texas, filed a patent in the US for the Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) RP process. This patent was issued in 1989 and SLS was later licensed to DTM Inc, which was later acquired by 3D Systems. 1989 was also the year that Scott Crump, a co-founder of Stratasys Inc. filed a patent for Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) — the proprietary technology that is still held by the company today, but is also the process used by many of the entry-level machines, based on the open source RepRap model, that are prolific today. The FDM patent was issued to Stratasys in 1992. In Europe, 1989 also saw the formation of EOS GmbH in Germany, founded by Hans Langer. After a dalliance with SL processes, EOS’ R&D focus was placed heavily on the laser sintering (LS) process, which has continued to go from strength to strength. Today, the EOS systems are recognized around the world for their quality output for industrial prototyping and production applications of 3D printing. EOS sold its first ‘Stereos’ system in 1990. The company’s direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) process resulted from an initial project with a division of Electrolux Finland, which was later acquired by EOS.

This patent was issued in 1989 and SLS was later licensed to DTM Inc, which was later acquired by 3D Systems. 1989 was also the year that Scott Crump, a co-founder of Stratasys Inc. filed a patent for Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) — the proprietary technology that is still held by the company today, but is also the process used by many of the entry-level machines, based on the open source RepRap model, that are prolific today. The FDM patent was issued to Stratasys in 1992. In Europe, 1989 also saw the formation of EOS GmbH in Germany, founded by Hans Langer. After a dalliance with SL processes, EOS’ R&D focus was placed heavily on the laser sintering (LS) process, which has continued to go from strength to strength. Today, the EOS systems are recognized around the world for their quality output for industrial prototyping and production applications of 3D printing. EOS sold its first ‘Stereos’ system in 1990. The company’s direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) process resulted from an initial project with a division of Electrolux Finland, which was later acquired by EOS.

Other 3D printing technologies and processes were also emerging during these years, namely Ballistic Particle Manufacturing (BPM) originally patented by William Masters, Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM) originally patented by Michael Feygin, Solid Ground Curing (SGC) originally patented by Itzchak Pomerantz et al and ‘three dimensional printing’ (3DP) originally patented by Emanuel Sachs et al. And so the early nineties witnessed a growing number of competing companies in the RP market but only three of the originals remain today — 3D Systems, EOS and Stratasys.

Throughout the 1990’s and early 2000’s a host of new technologies continued to be introduced, still focused wholly on industrial applications and while they were still largely processes for prototyping applications, R&D was also being conducted by the more advanced technology providers for specific tooling, casting and direct manufacturing applications. This saw the emergence of new terminology, namely Rapid Tooling (RT), Rapid Casting and Rapid Manufacturing (RM) respectively.

In terms of commercial operations, Sanders Prototype (later Solidscape) and ZCorporation were set up in 1996, Arcam was established in 1997, Objet Geometries launched in 1998, MCP Technologies (an established vacuum casting OEM) introduced the SLM technology in 2000, EnvisionTec was founded in 2002, ExOne was established in 2005 as a spin-off from the Extrude Hone Corporation and Sciaky Inc was pioneering its own additive process based on its proprietary electron beam welding technology. These companies all served to swell the ranks of Western companies operating across a global market. The terminology had also evolved with a proliferation of manufacturing applications and the accepted umbrella term for all of the processes was Additive Manufacturing (AM). Notably, there were many parallel developments taking place in the Eastern hemisphere. However, these technologies, while significant in themselves and enjoying some local success, did not really impact the global market at that time.

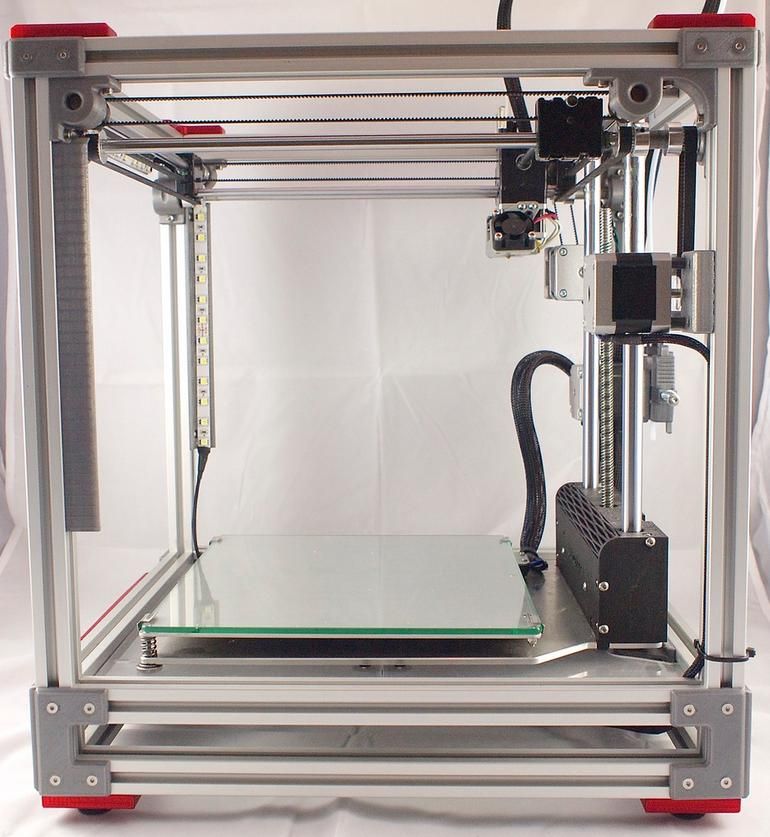

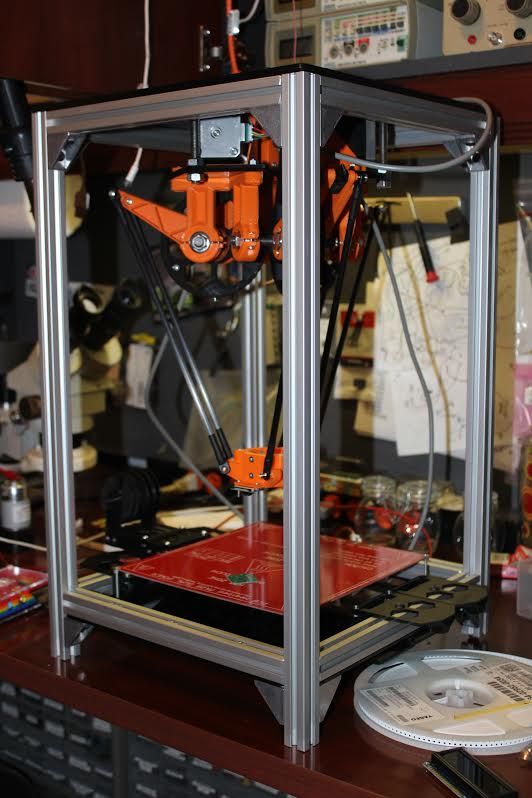

During the mid noughties, the sector started to show signs of distinct diversification with two specific areas of emphasis that are much more clearly defined today. First, there was the high end of 3D printing, still very expensive systems, which were geared towards part production for high value, highly engineered, complex parts. This is still ongoing — and growing — but the results are only now really starting to become visible in production applications across the aerospace, automotive, medical and fine jewellery sectors, as years of R&D and qualification are now paying off. A great deal still remains behind closed doors and/or under non-disclosure agreements (NDA). At the other end of the spectrum, some of the 3D printing system manufacturers were developing and advancing ‘concept modellers’, as they were called at the time. Specifically, these were 3D printers that kept the focus on improving concept development and functional prototyping, that were being developed specifically as office- and user-friendly, cost-effective systems. The prelude to today’s desktop machines. However, these systems were all still very much for industrial applications.

The prelude to today’s desktop machines. However, these systems were all still very much for industrial applications.

Looking back, this was really the calm before the storm.

At the lower end of the market — the 3D printers that today are seen as being in the mid range — a price war emerged together with incremental improvements in printing accuracy, speed and materials.

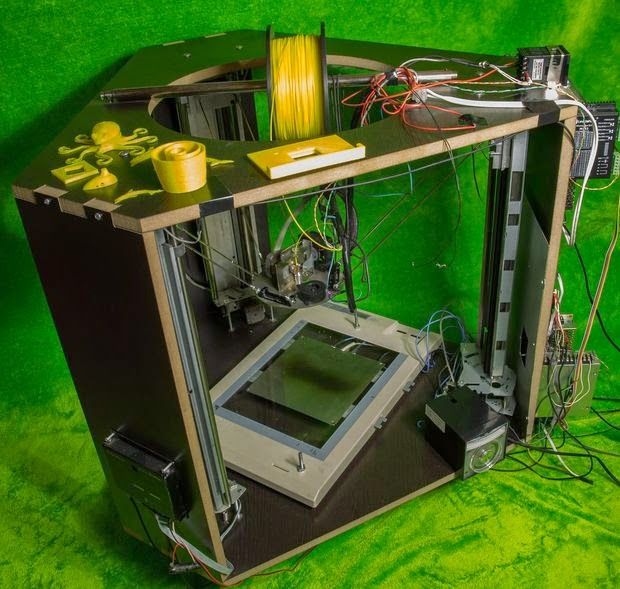

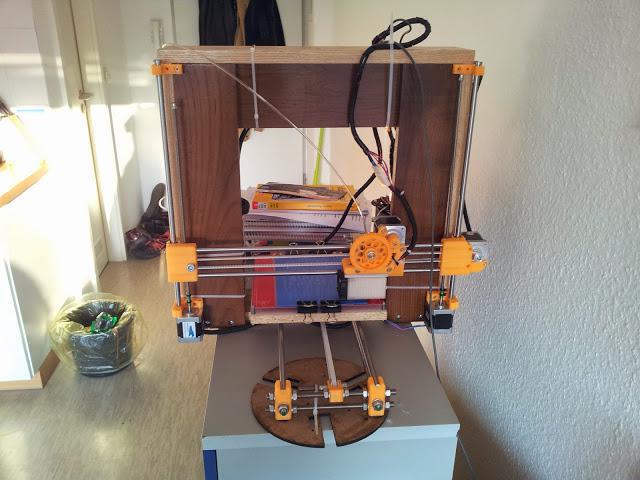

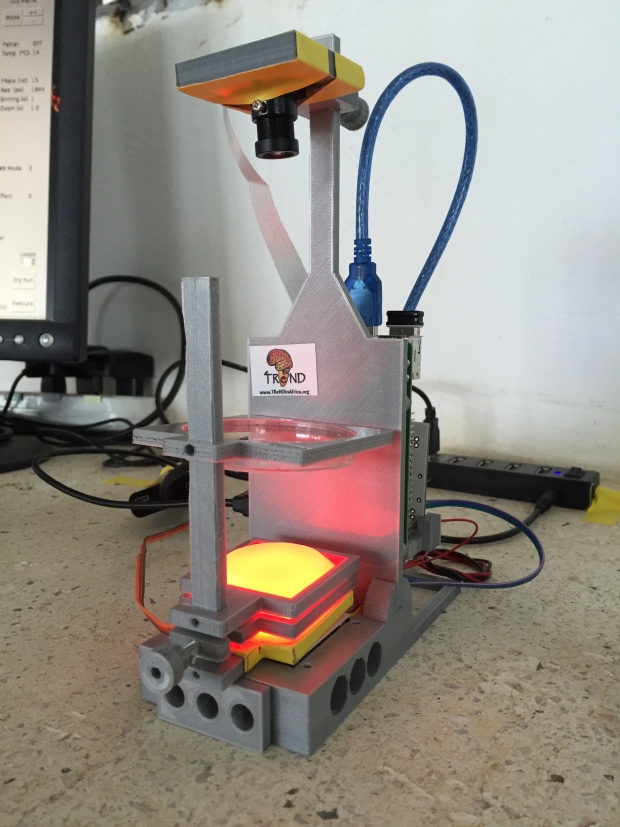

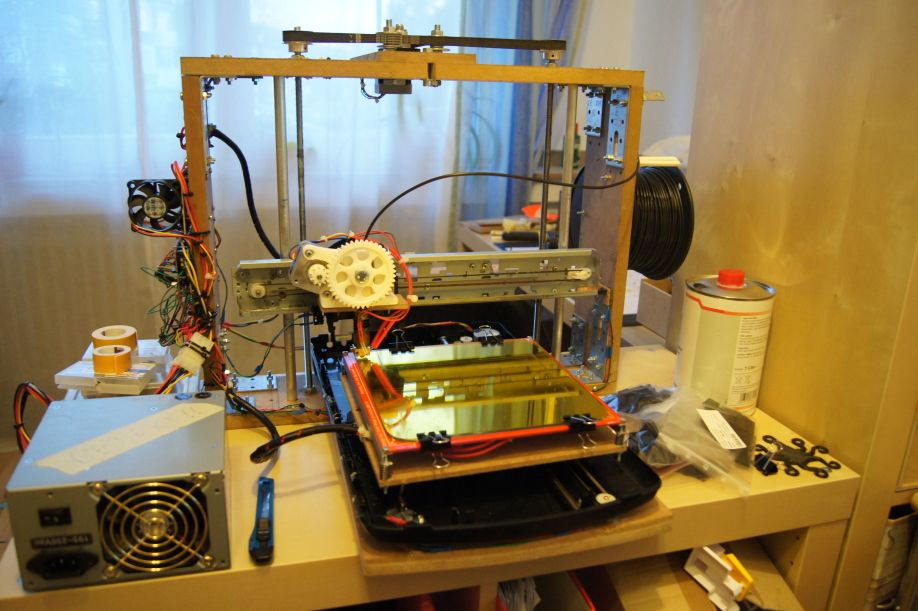

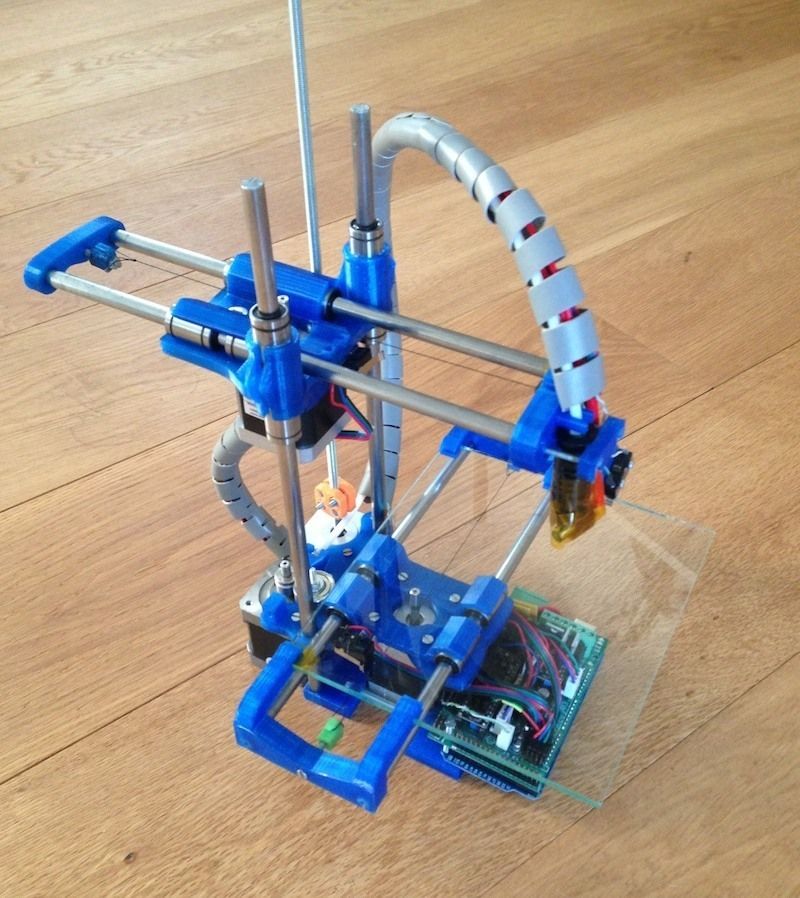

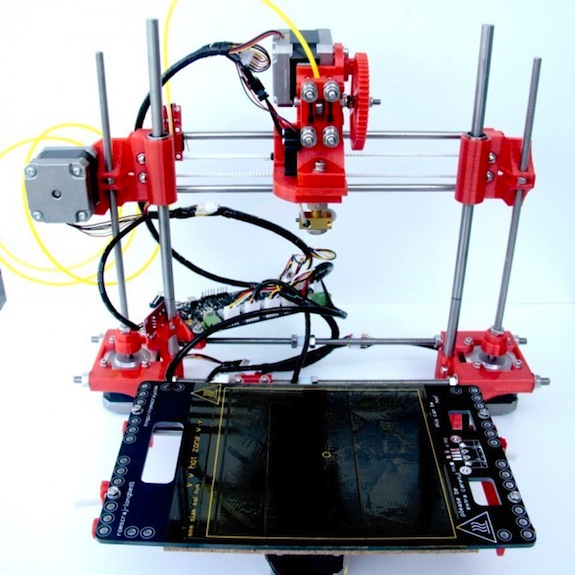

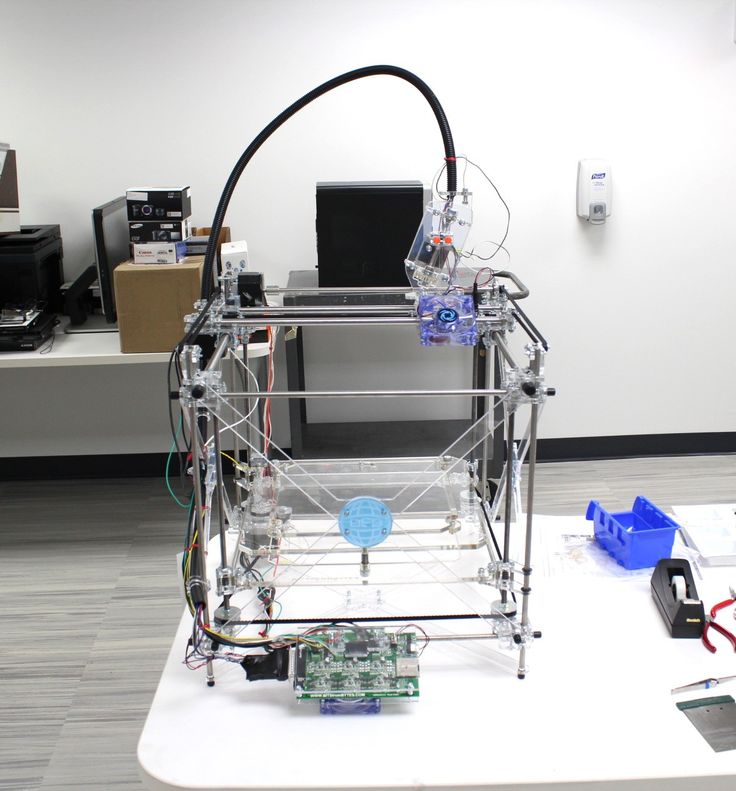

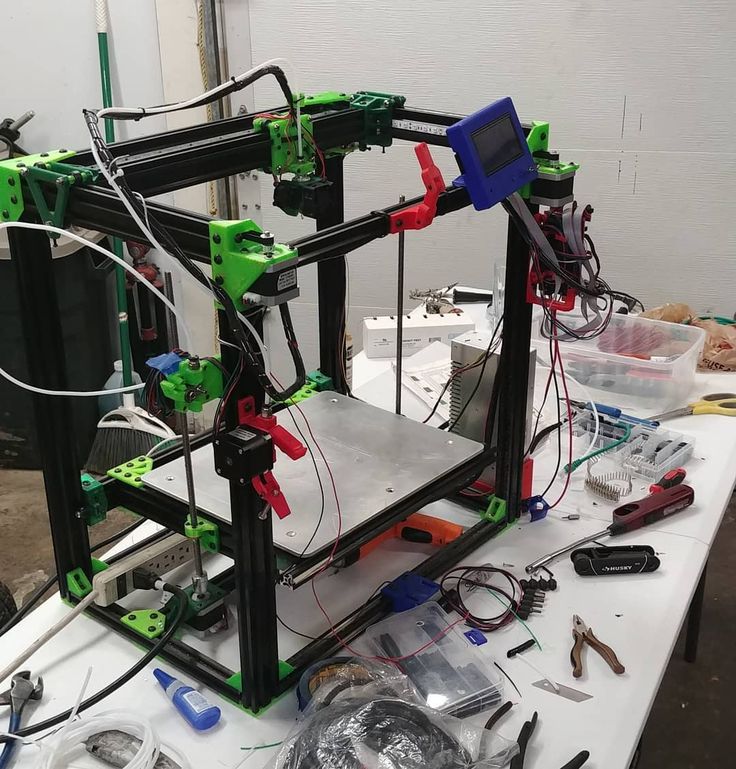

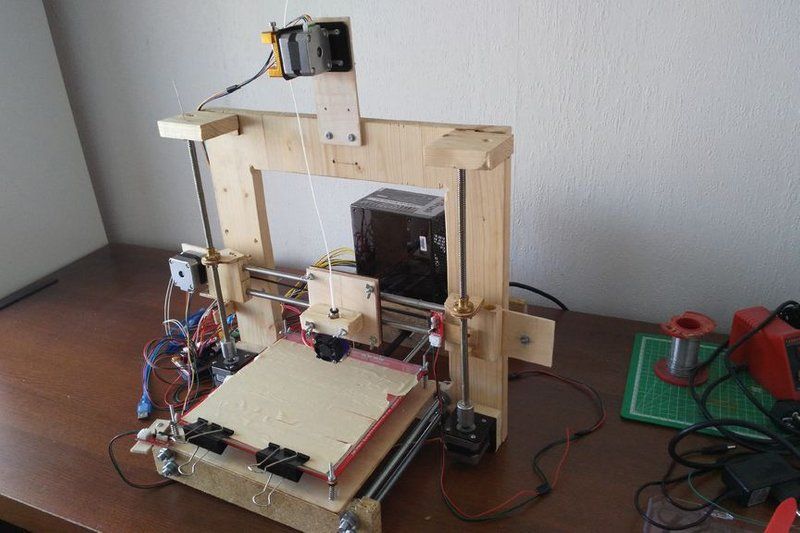

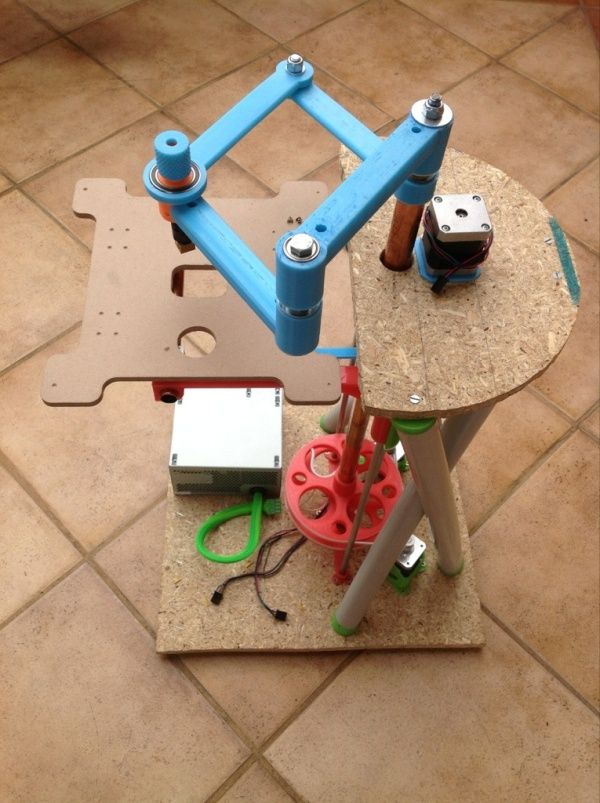

In 2007, the market saw the first system under $10,000 from 3D Systems, but this never quite hit the mark that it was supposed to. This was partly due to the system itself, but also other market influences. The holy grail at that time was to get a 3D printer under $5000 — this was seen by many industry insiders, users and commentators as the key to opening up 3D printing technology to a much wider audience. For much of that year, the arrival of the highly-anticipated Desktop Factory — which many predicted would be the fulfillment of that holy grail — was heralded as the one to watch. It came to nothing as the organization faltered in the run up to production. Desktop Factory and its leader, Cathy Lewis, were acquired, along with the IP, by 3D Systems in 2008 and all but vanished. As it turned out though, 2007 was actually the year that did mark the turning point for accessible 3D printing technology — even though few realized it at the time — as the RepRap phenomenon took root. Dr Bowyer conceived the RepRap concept of an open source, self-replicating 3D printer as early as 2004, and the seed was germinated in the following years with some heavy slog from his team at Bath, most notably Vik Oliver and Rhys Jones, who developed the concept through to working prototypes of a 3D printer using the deposition process. 2007 was the year the shoots started to show through and this embryonic, open source 3D printing movement started to gain visibility.

Desktop Factory and its leader, Cathy Lewis, were acquired, along with the IP, by 3D Systems in 2008 and all but vanished. As it turned out though, 2007 was actually the year that did mark the turning point for accessible 3D printing technology — even though few realized it at the time — as the RepRap phenomenon took root. Dr Bowyer conceived the RepRap concept of an open source, self-replicating 3D printer as early as 2004, and the seed was germinated in the following years with some heavy slog from his team at Bath, most notably Vik Oliver and Rhys Jones, who developed the concept through to working prototypes of a 3D printer using the deposition process. 2007 was the year the shoots started to show through and this embryonic, open source 3D printing movement started to gain visibility.

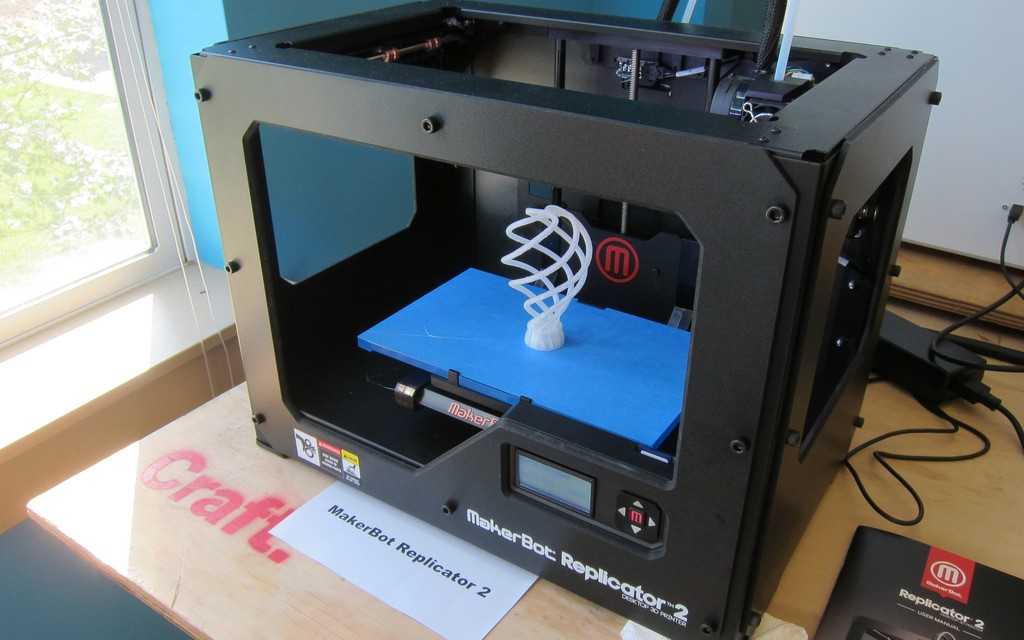

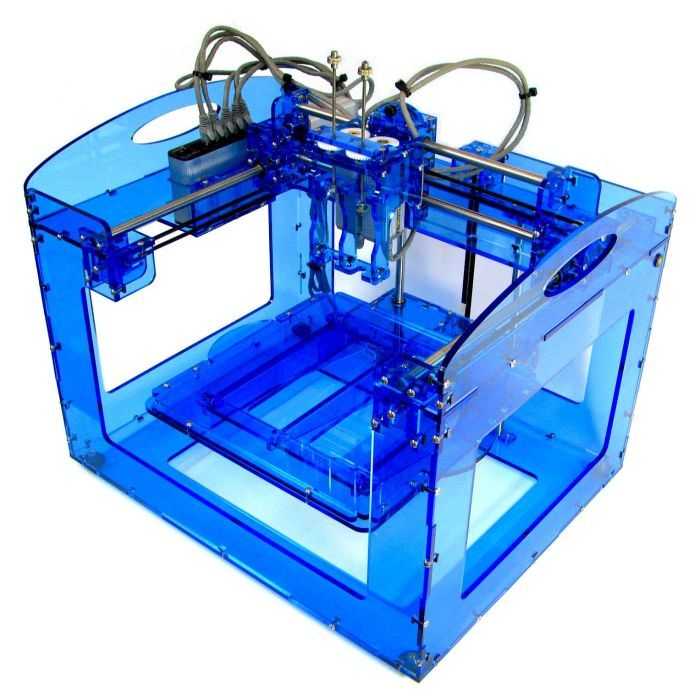

But it wasn’t until January 2009 that the first commercially available 3D printer – in kit form and based on the RepRap concept – was offered for sale. This was the BfB RapMan 3D printer. Closely followed by Makerbot Industries in April the same year, the founders of which were heavily involved in the development of RepRap until they departed from the Open Source philosophy following extensive investment. Since 2009, a host of similar deposition printers have emerged with marginal unique selling points (USPs) and they continue to do so. The interesting dichotomy here is that, while the RepRap phenomenon has given rise to a whole new sector of commercial, entry-level 3D printers, the ethos of the RepRap community is all about Open Source developments for 3D printing and keeping commercialization at bay.

Since 2009, a host of similar deposition printers have emerged with marginal unique selling points (USPs) and they continue to do so. The interesting dichotomy here is that, while the RepRap phenomenon has given rise to a whole new sector of commercial, entry-level 3D printers, the ethos of the RepRap community is all about Open Source developments for 3D printing and keeping commercialization at bay.

2012 was the year that alternative 3D printing processes were introduced at the entry level of the market. The B9Creator (utilising DLP technology) came first in June, followed by the Form 1 (utilising stereolithography) in December. Both were launched via the funding site Kickstarter — and both enjoyed huge success.

As a result of the market divergence, significant advances at the industrial level with capabilities and applications, dramatic increase in awareness and uptake across a growing maker movement, 2012 was also the year that many different mainstream media channels picked up on the technology. 2013 was a year of significant growth and consolidation. One of the most notable moves was the acquisition of Makerbot by Stratasys.

2013 was a year of significant growth and consolidation. One of the most notable moves was the acquisition of Makerbot by Stratasys.

Heralded as the 2nd, 3rd and, sometimes even, 4th Industrial Revolution by some, what cannot be denied is the impact that 3D printing is having on the industrial sector and the huge potential that 3D printing is demonstrating for the future of consumers. What shape that potential will take is still unfolding before us.

03 - Technology

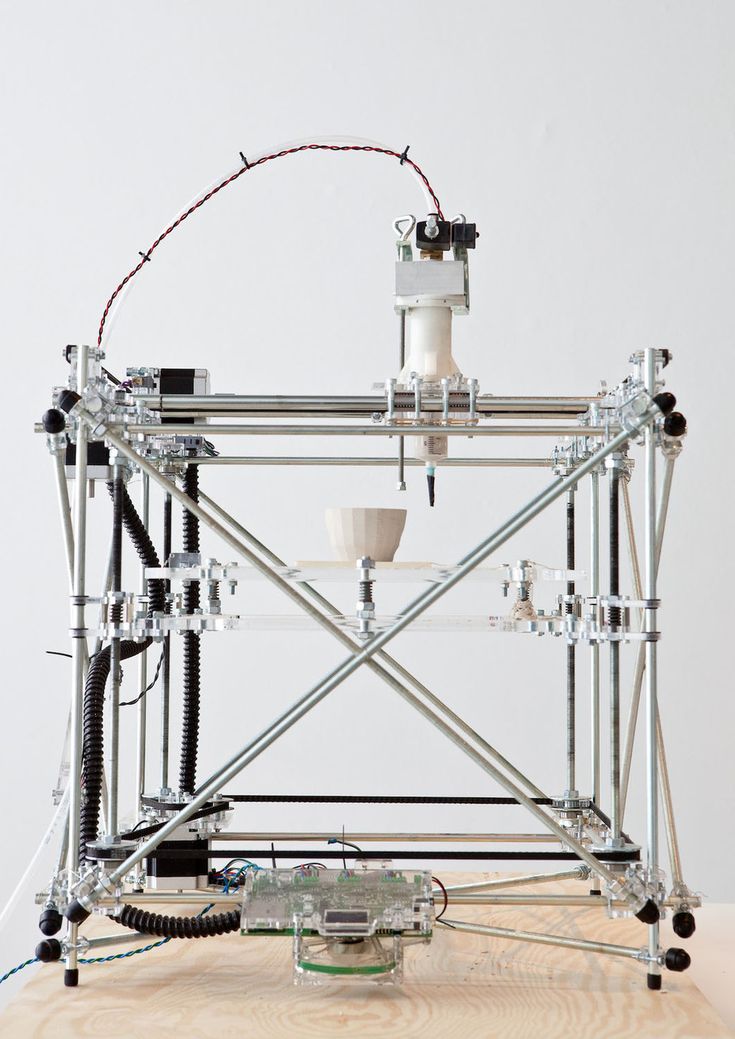

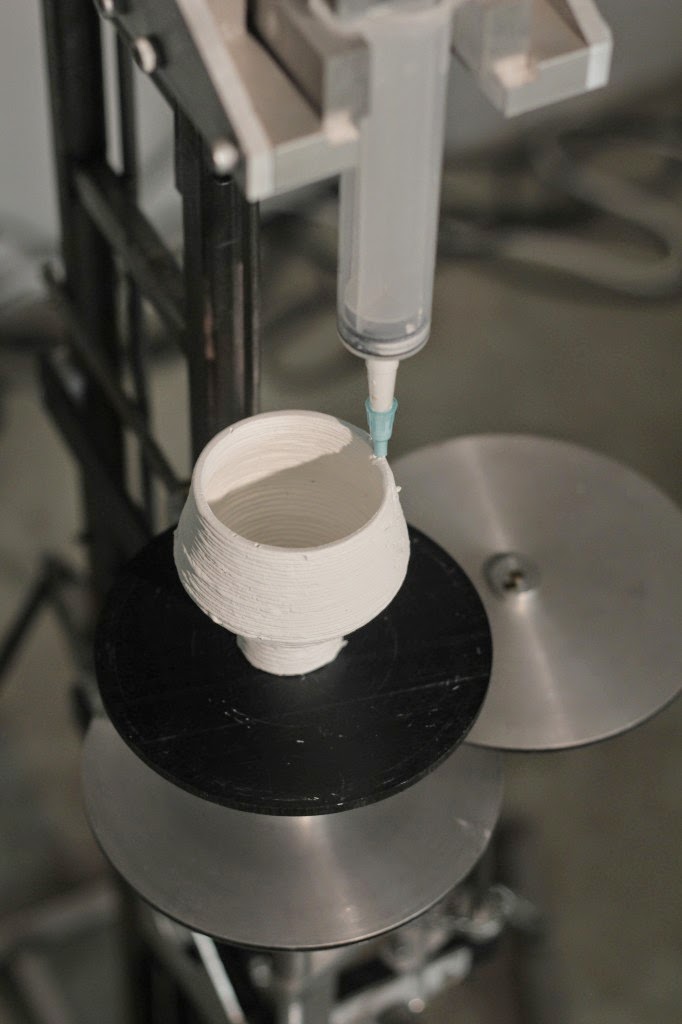

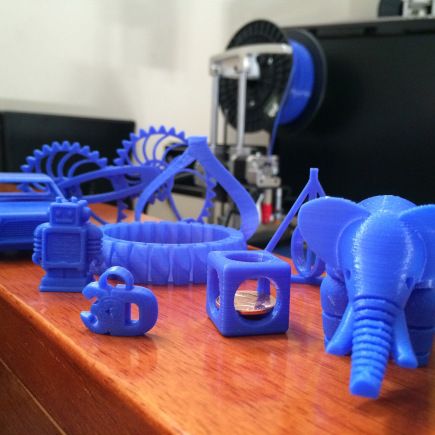

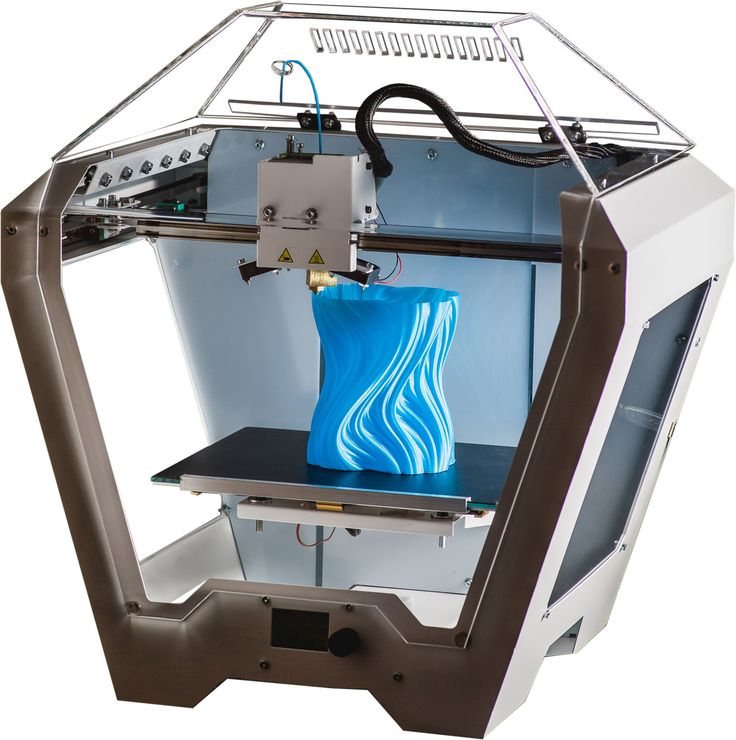

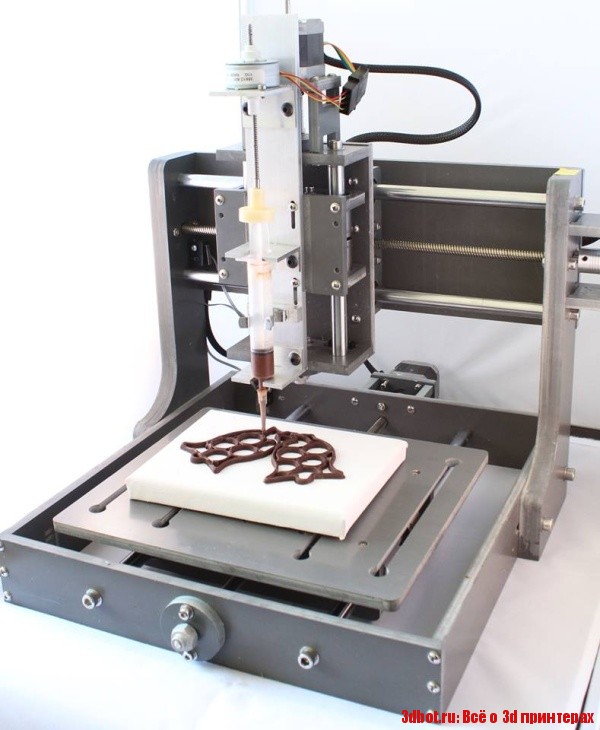

The starting point for any 3D printing process is a 3D digital model, which can be created using a variety of 3D software programmes — in industry this is 3D CAD, for Makers and Consumers there are simpler, more accessible programmes available — or scanned with a 3D scanner. The model is then ‘sliced’ into layers, thereby converting the design into a file readable by the 3D printer. The material processed by the 3D printer is then layered according to the design and the process. As stated, there are a number of different types of 3D printing technologies, which process different materials in different ways to create the final object. Functional plastics, metals, ceramics and sand are, now, all routinely used for industrial prototyping and production applications. Research is also being conducted for 3D printing bio materials and different types of food. Generally speaking though, at the entry level of the market, materials are much more limited. Plastic is currently the only widely used material — usually ABS or PLA, but there are a growing number of alternatives, including Nylon. There is also a growing number of entry level machines that have been adapted for foodstuffs, such as sugar and chocolate.

Functional plastics, metals, ceramics and sand are, now, all routinely used for industrial prototyping and production applications. Research is also being conducted for 3D printing bio materials and different types of food. Generally speaking though, at the entry level of the market, materials are much more limited. Plastic is currently the only widely used material — usually ABS or PLA, but there are a growing number of alternatives, including Nylon. There is also a growing number of entry level machines that have been adapted for foodstuffs, such as sugar and chocolate.

How it Works

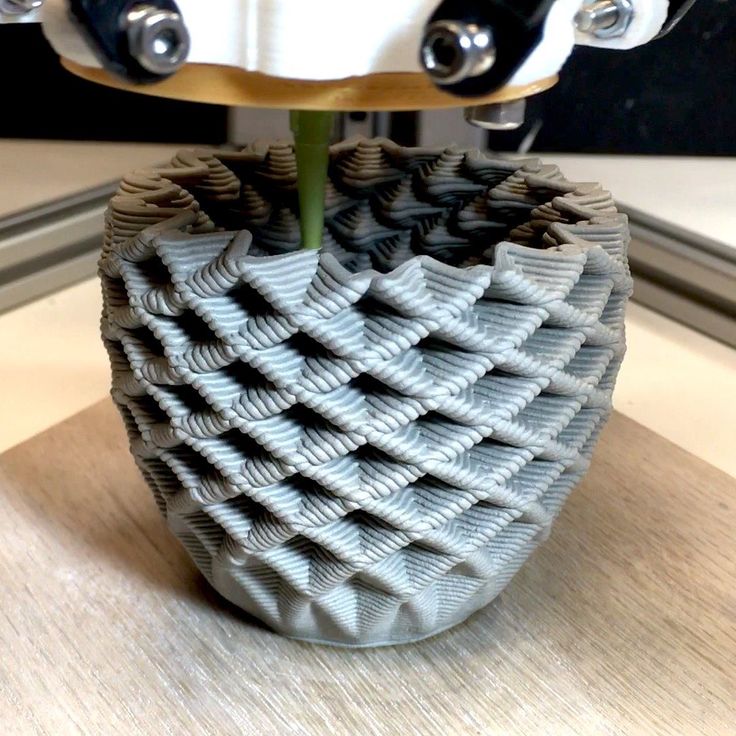

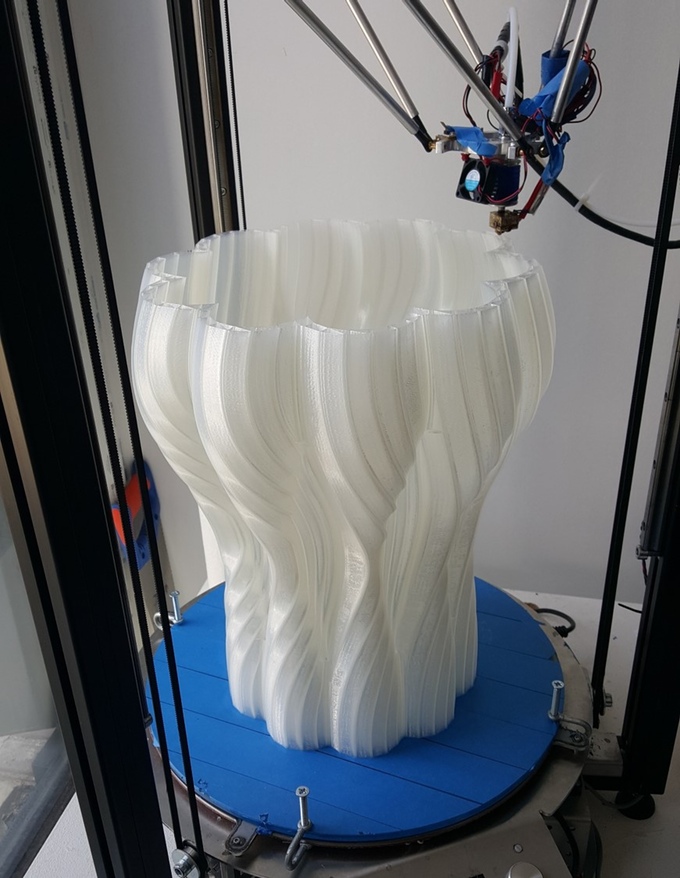

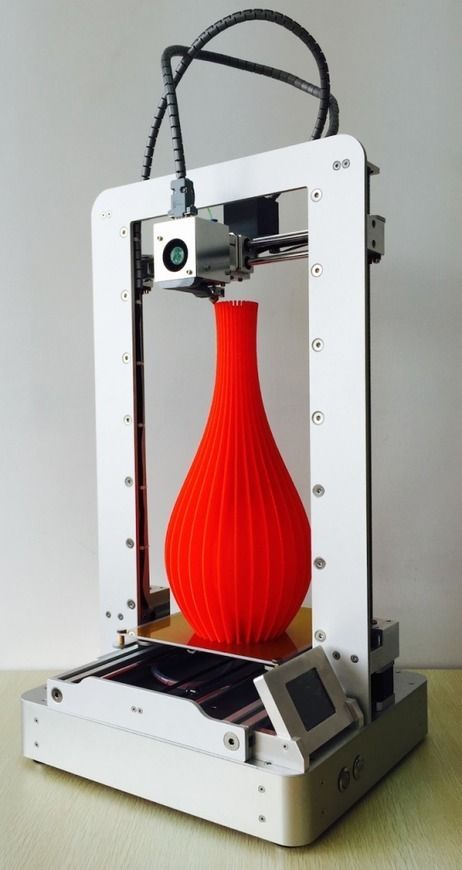

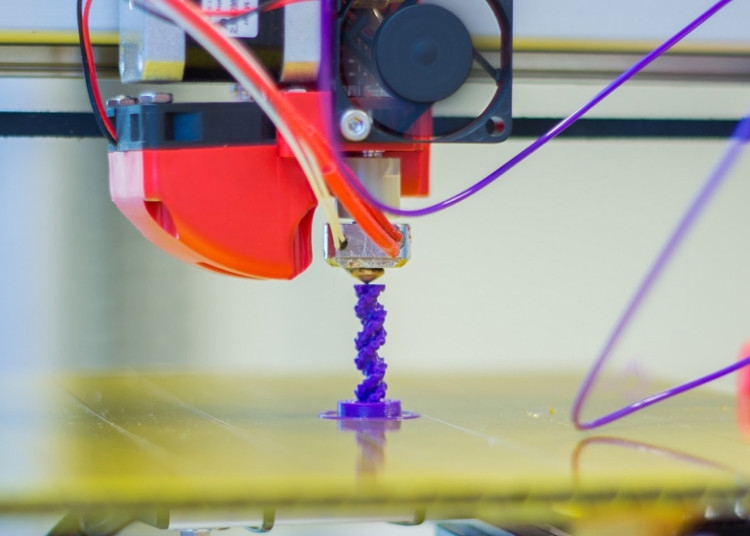

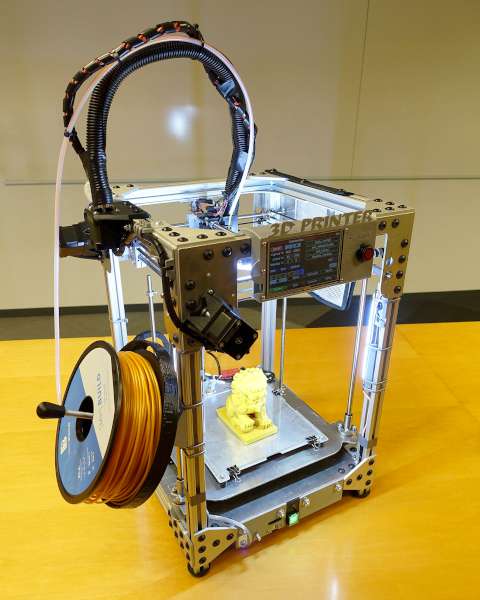

The different types of 3D printers each employ a different technology that processes different materials in different ways. It is important to understand that one of the most basic limitations of 3D printing — in terms of materials and applications — is that there is no ‘one solution fits all’. For example some 3D printers process powdered materials (nylon, plastic, ceramic, metal), which utilize a light/heat source to sinter/melt/fuse layers of the powder together in the defined shape. Others process polymer resin materials and again utilize a light/laser to solidify the resin in ultra thin layers. Jetting of fine droplets is another 3D printing process, reminiscent of 2D inkjet printing, but with superior materials to ink and a binder to fix the layers. Perhaps the most common and easily recognized process is deposition, and this is the process employed by the majority of entry-level 3D printers. This process extrudes plastics, commonly PLA or ABS, in filament form through a heated extruder to form layers and create the predetermined shape.

Others process polymer resin materials and again utilize a light/laser to solidify the resin in ultra thin layers. Jetting of fine droplets is another 3D printing process, reminiscent of 2D inkjet printing, but with superior materials to ink and a binder to fix the layers. Perhaps the most common and easily recognized process is deposition, and this is the process employed by the majority of entry-level 3D printers. This process extrudes plastics, commonly PLA or ABS, in filament form through a heated extruder to form layers and create the predetermined shape.

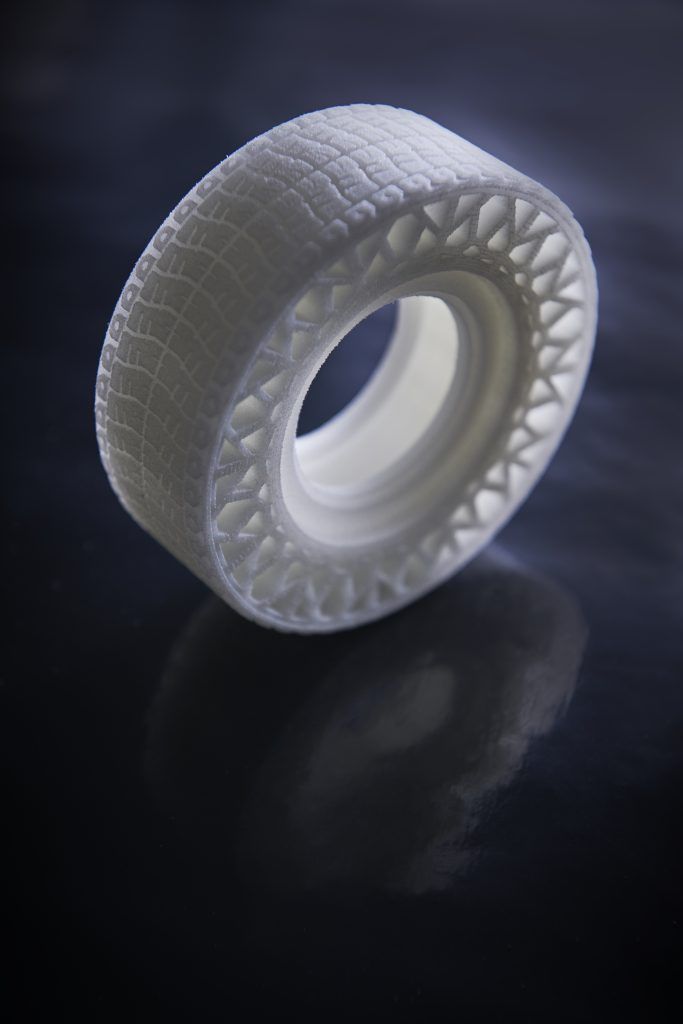

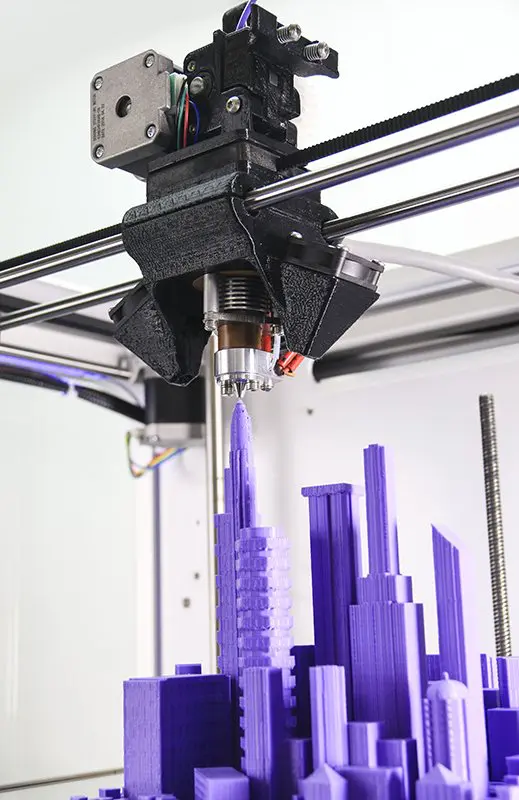

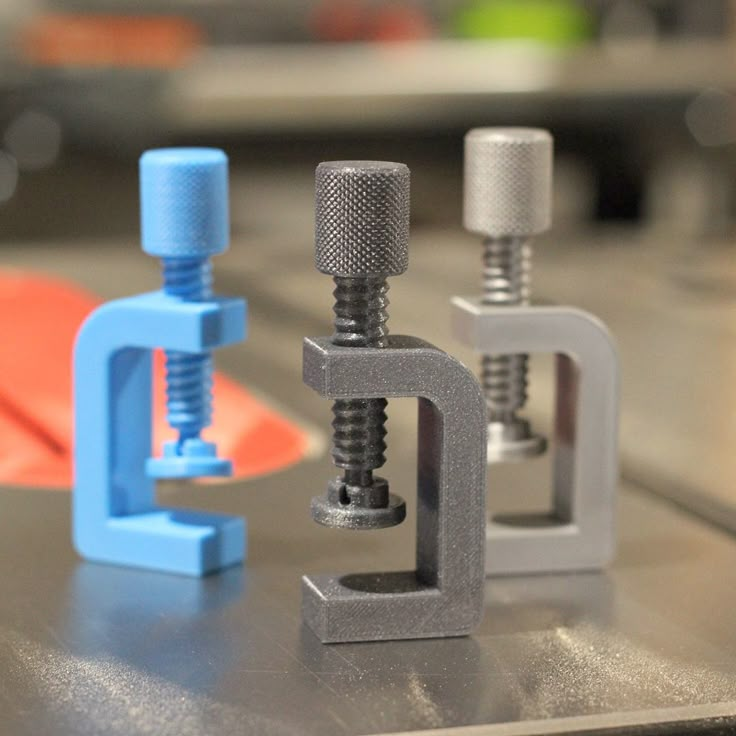

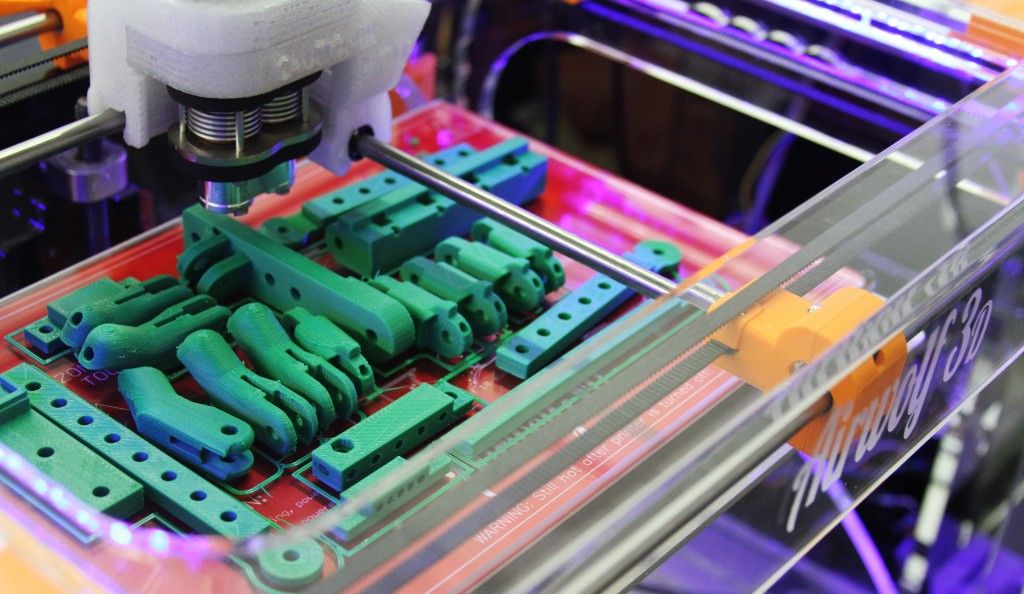

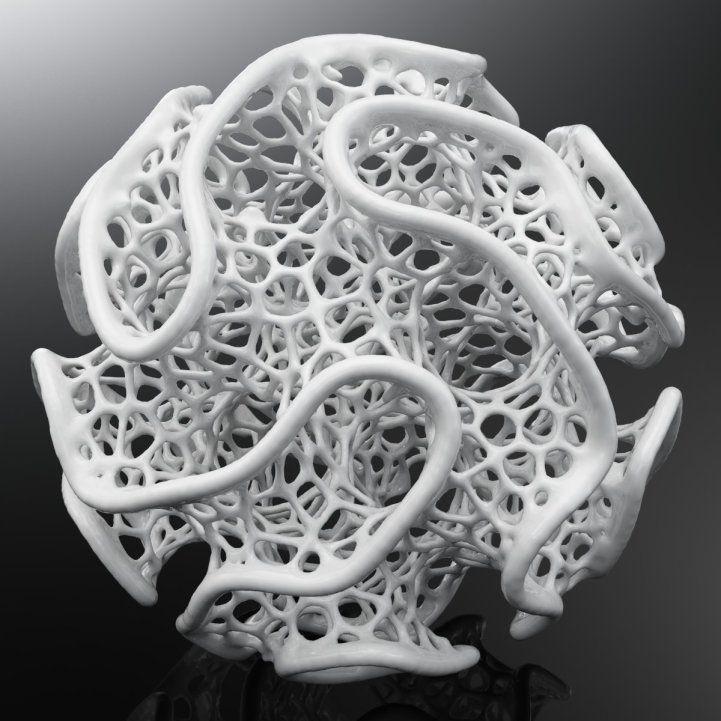

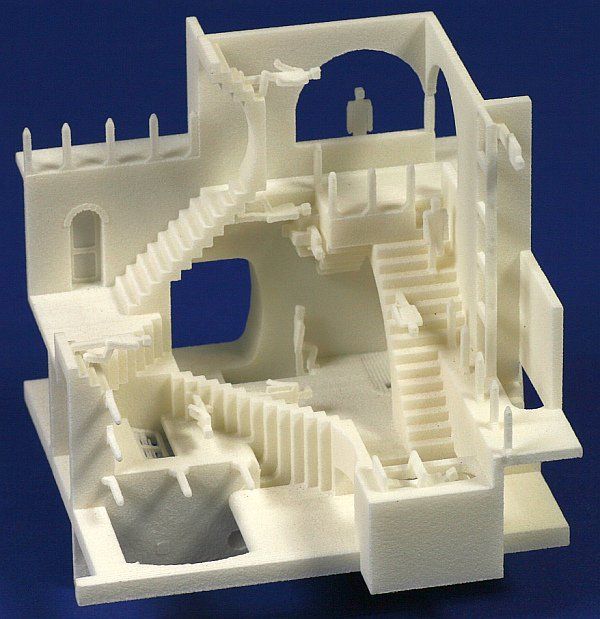

Because parts can be printed directly, it is possible to produce very detailed and intricate objects, often with functionality built in and negating the need for assembly.

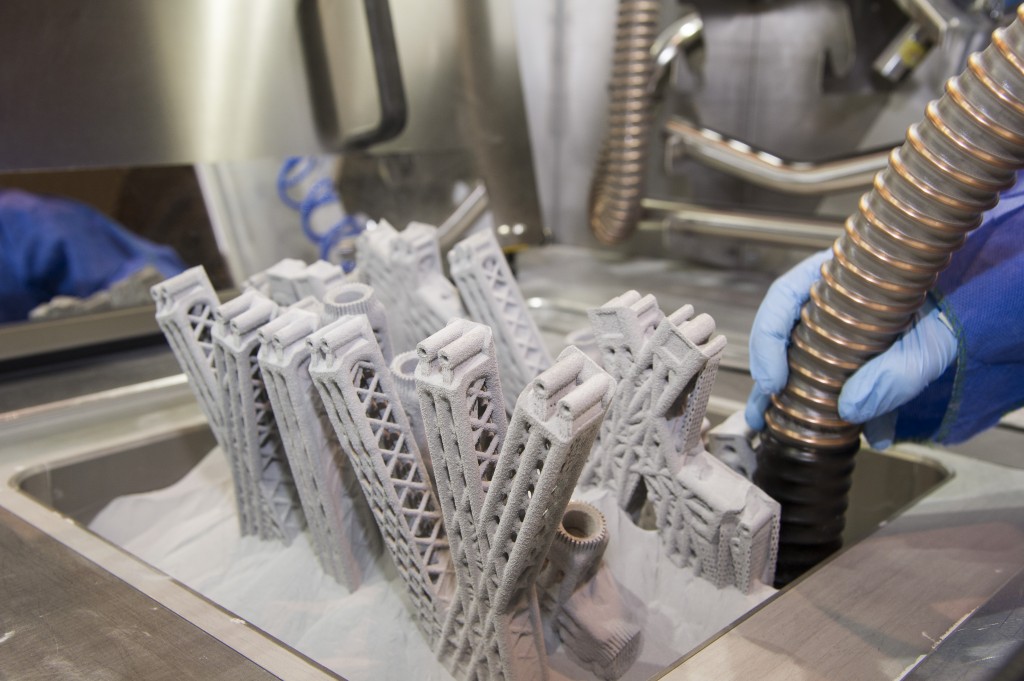

However, another important point to stress is that none of the 3D printing processes come as plug and play options as of today. There are many steps prior to pressing print and more once the part comes off the printer — these are often overlooked. Apart from the realities of designing for 3D printing, which can be demanding, file preparation and conversion can also prove time-consuming and complicated, particularly for parts that demand intricate supports during the build process. However there are continual updates and upgrades of software for these functions and the situation is improving. Furthermore, once off the printer, many parts will need to undergo finishing operations. Support removal is an obvious one for processes that demand support, but others include sanding, lacquer, paint or other types of traditional finishing touches, which all typically need to be done by hand and require skill and/or time and patience.

However there are continual updates and upgrades of software for these functions and the situation is improving. Furthermore, once off the printer, many parts will need to undergo finishing operations. Support removal is an obvious one for processes that demand support, but others include sanding, lacquer, paint or other types of traditional finishing touches, which all typically need to be done by hand and require skill and/or time and patience.

04 - Processes

Stereolithography

Stereolithography (SL) is widely recognized as the first 3D printing process; it was certainly the first to be commercialised. SL is a laser-based process that works with photopolymer resins, that react with the laser and cure to form a solid in a very precise way to produce very accurate parts. It is a complex process, but simply put, the photopolymer resin is held in a vat with a movable platform inside. A laser beam is directed in the X-Y axes across the surface of the resin according to the 3D data supplied to the machine (the . stl file), whereby the resin hardens precisely where the laser hits the surface. Once the layer is completed, the platform within the vat drops down by a fraction (in the Z axis) and the subsequent layer is traced out by the laser. This continues until the entire object is completed and the platform can be raised out of the vat for removal.

stl file), whereby the resin hardens precisely where the laser hits the surface. Once the layer is completed, the platform within the vat drops down by a fraction (in the Z axis) and the subsequent layer is traced out by the laser. This continues until the entire object is completed and the platform can be raised out of the vat for removal.

Because of the nature of the SL process, it requires support structures for some parts, specifically those with overhangs or undercuts. These structures need to be manually removed.

In terms of other post processing steps, many objects 3D printed using SL need to be cleaned and cured. Curing involves subjecting the part to intense light in an oven-like machine to fully harden the resin.

Stereolithography is generally accepted as being one of the most accurate 3D printing processes with excellent surface finish. However limiting factors include the post-processing steps required and the stability of the materials over time, which can become more brittle.

DLP — or digital light processing — is a similar process to stereolithography in that it is a 3D printing process that works with photopolymers. The major difference is the light source. DLP uses a more conventional light source, such as an arc lamp, with a liquid crystal display panel or a deformable mirror device (DMD), which is applied to the entire surface of the vat of photopolymer resin in a single pass, generally making it faster than SL.

Also like SL, DLP produces highly accurate parts with excellent resolution, but its similarities also include the same requirements for support structures and post-curing. However, one advantage of DLP over SL is that only a shallow vat of resin is required to facilitate the process, which generally results in less waste and lower running costs.

Laser Sintering / Laser Melting

Laser sintering and laser melting are interchangeable terms that refer to a laser based 3D printing process that works with powdered materials. The laser is traced across a powder bed of tightly compacted powdered material, according to the 3D data fed to the machine, in the X-Y axes. As the laser interacts with the surface of the powdered material it sinters, or fuses, the particles to each other forming a solid. As each layer is completed the powder bed drops incrementally and a roller smoothes the powder over the surface of the bed prior to the next pass of the laser for the subsequent layer to be formed and fused with the previous layer.

As the laser interacts with the surface of the powdered material it sinters, or fuses, the particles to each other forming a solid. As each layer is completed the powder bed drops incrementally and a roller smoothes the powder over the surface of the bed prior to the next pass of the laser for the subsequent layer to be formed and fused with the previous layer.

The build chamber is completely sealed as it is necessary to maintain a precise temperature during the process specific to the melting point of the powdered material of choice. Once finished, the entire powder bed is removed from the machine and the excess powder can be removed to leave the ‘printed’ parts. One of the key advantages of this process is that the powder bed serves as an in-process support structure for overhangs and undercuts, and therefore complex shapes that could not be manufactured in any other way are possible with this process.

However, on the downside, because of the high temperatures required for laser sintering, cooling times can be considerable. Furthermore, porosity has been an historical issue with this process, and while there have been significant improvements towards fully dense parts, some applications still necessitate infiltration with another material to improve mechanical characteristics.

Furthermore, porosity has been an historical issue with this process, and while there have been significant improvements towards fully dense parts, some applications still necessitate infiltration with another material to improve mechanical characteristics.

Laser sintering can process plastic and metal materials, although metal sintering does require a much higher powered laser and higher in-process temperatures. Parts produced with this process are much stronger than with SL or DLP, although generally the surface finish and accuracy is not as good.

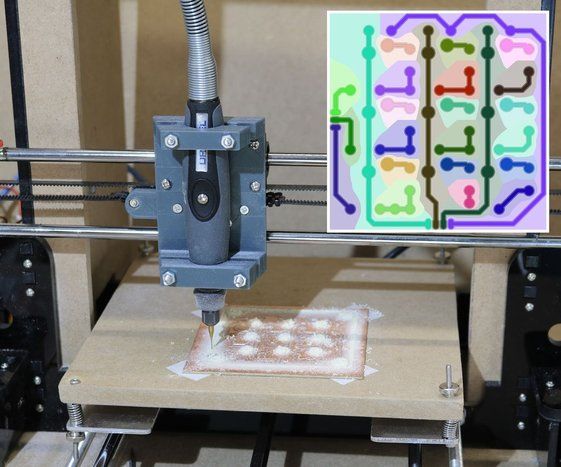

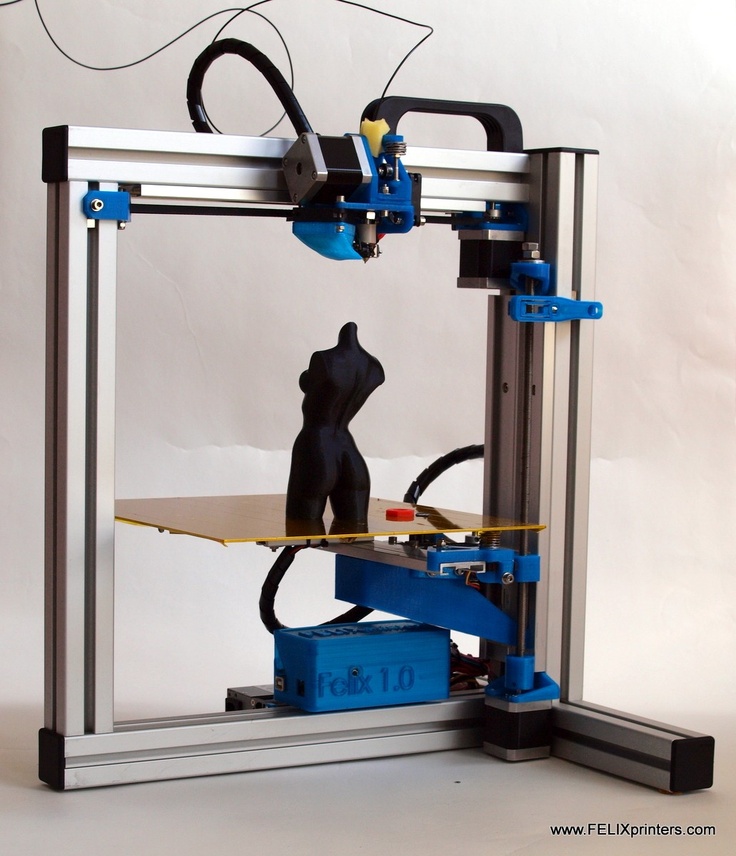

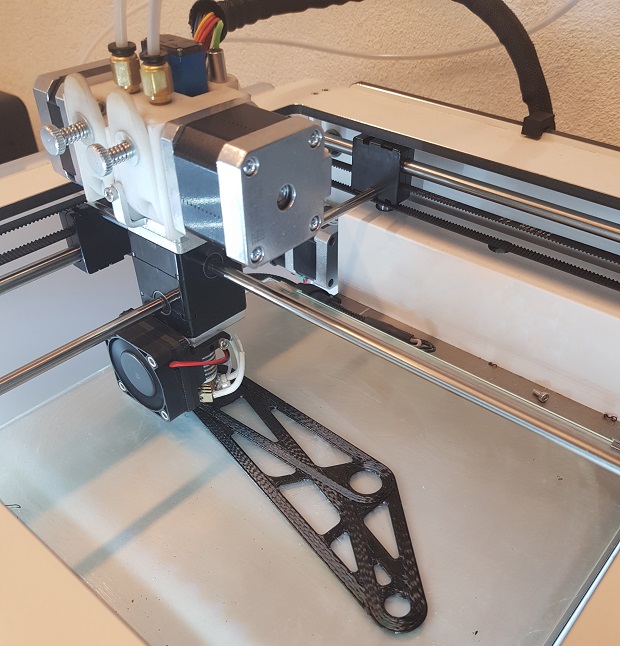

Extrusion / FDM / FFF

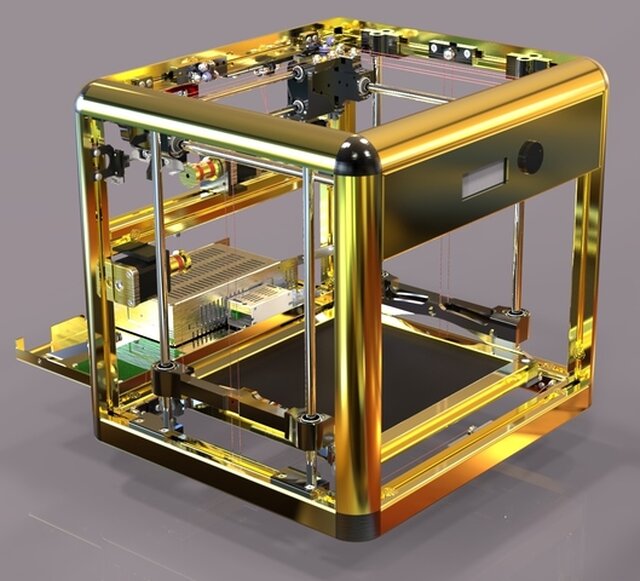

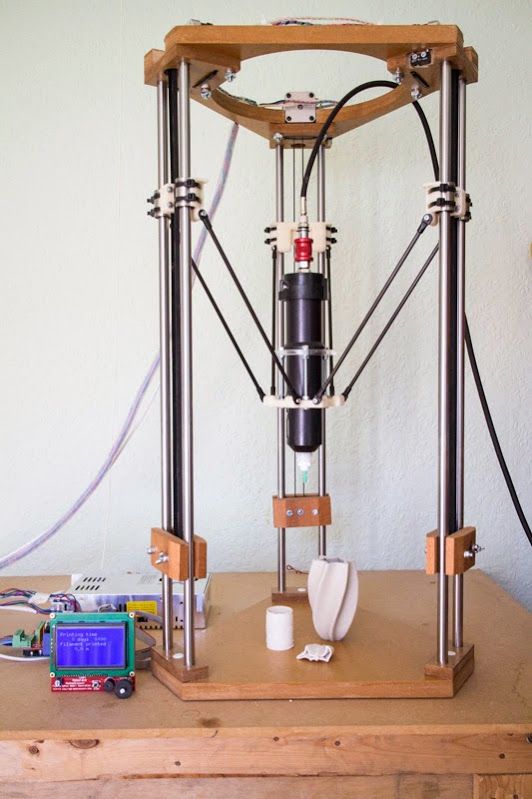

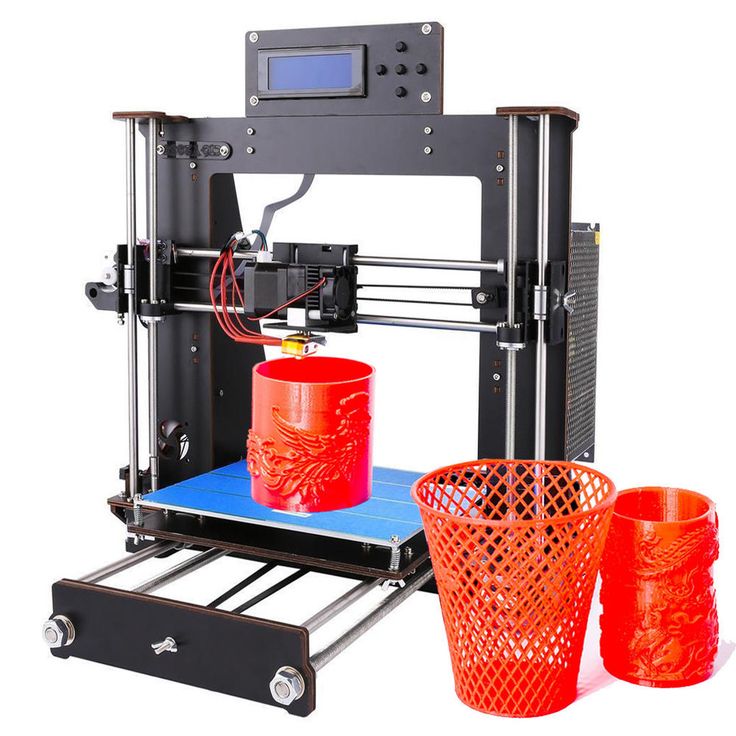

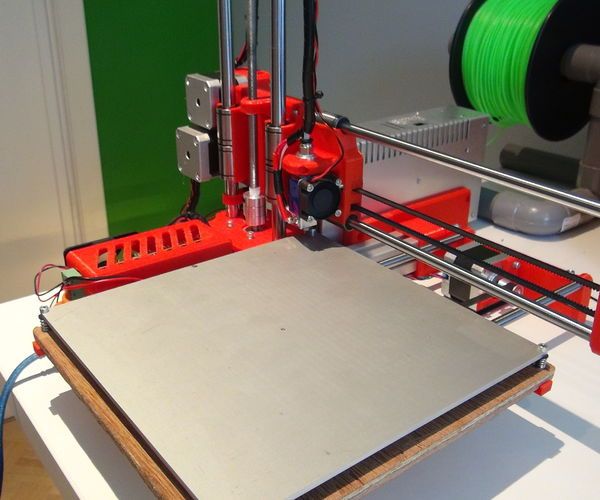

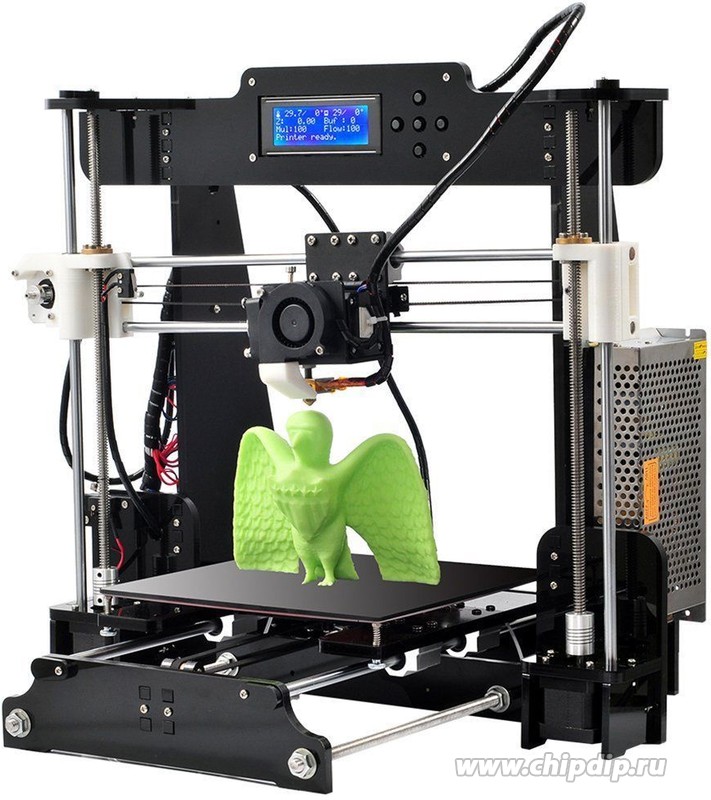

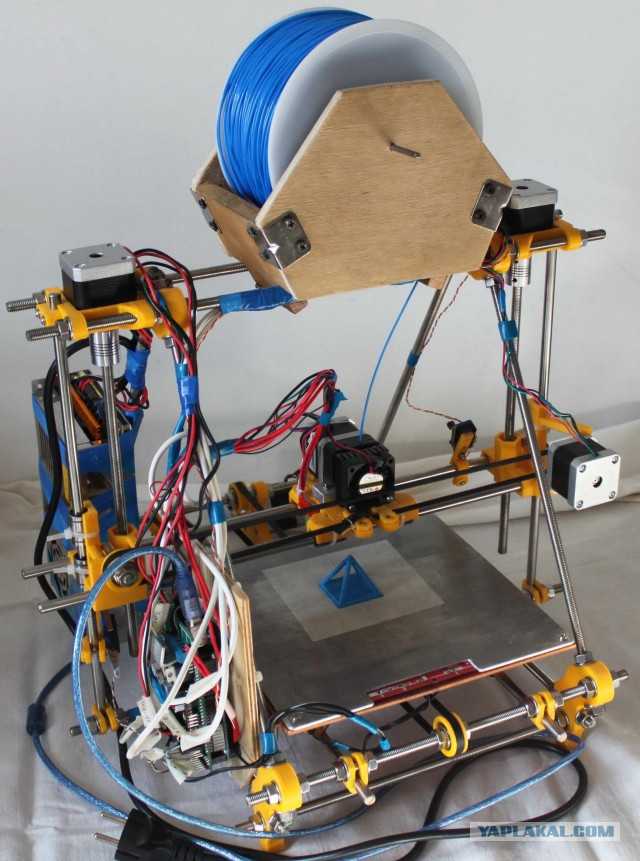

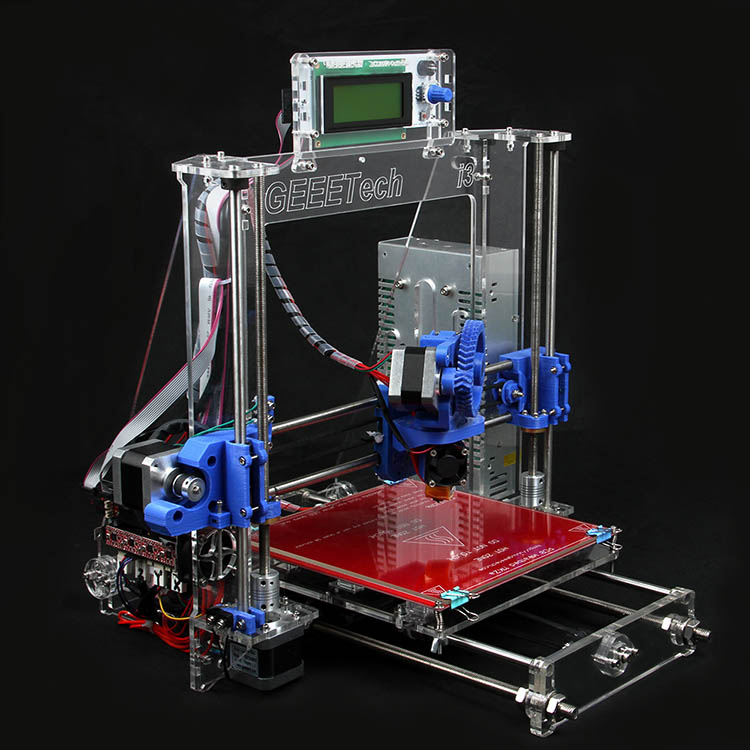

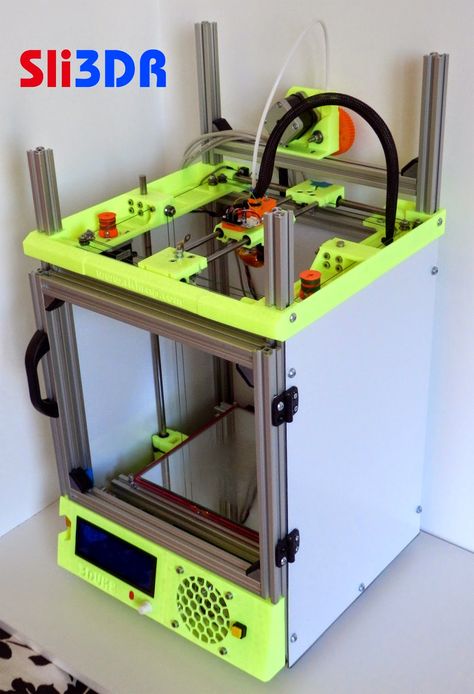

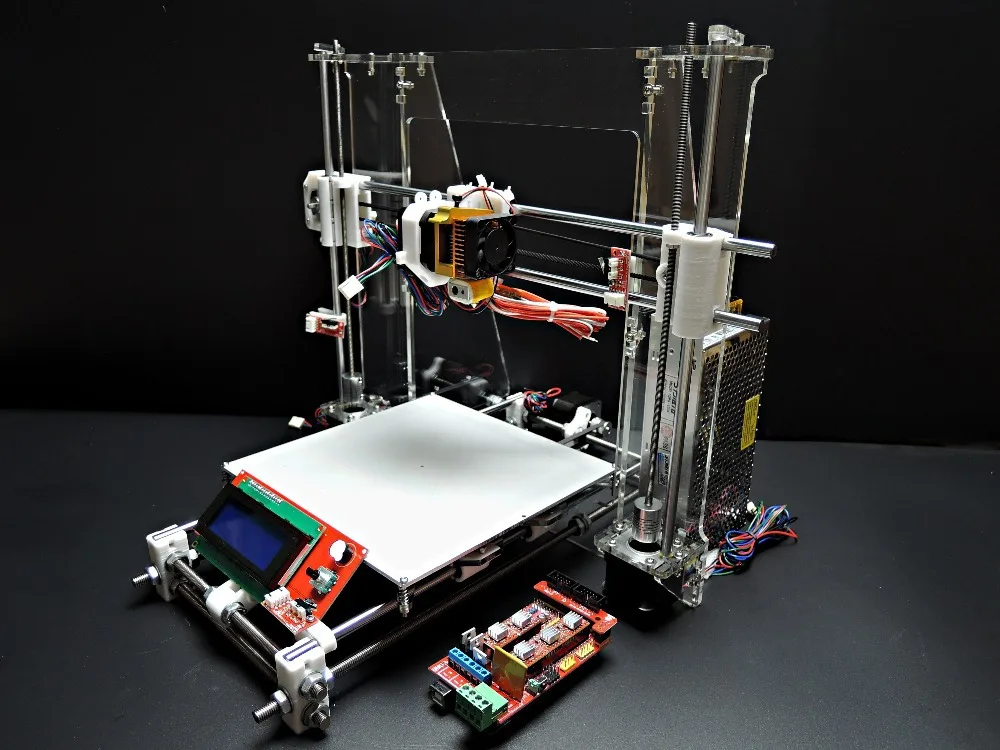

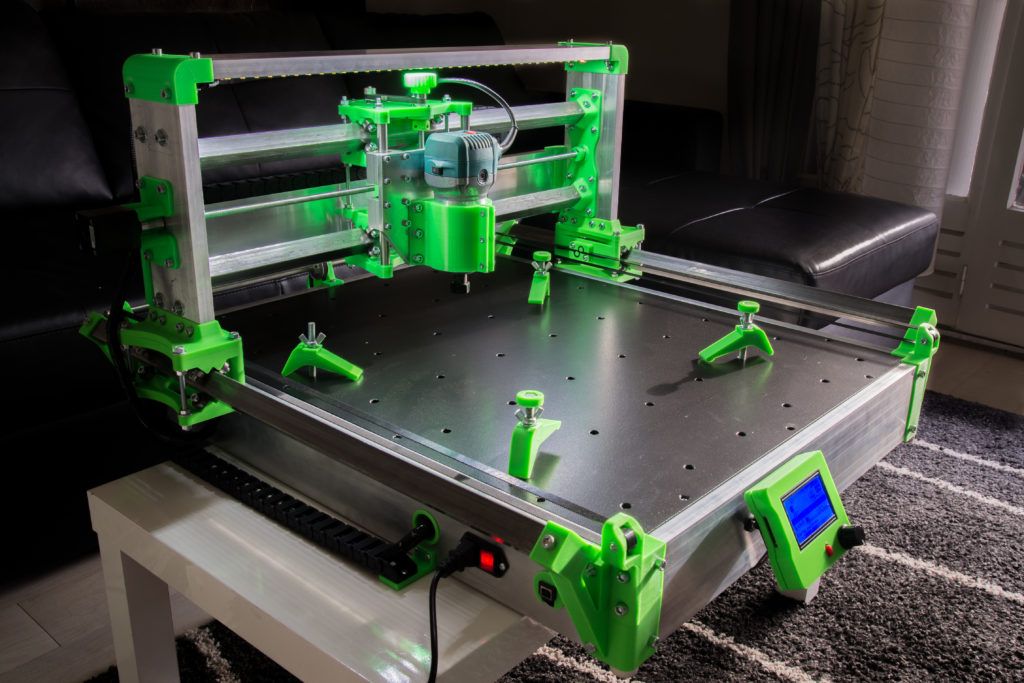

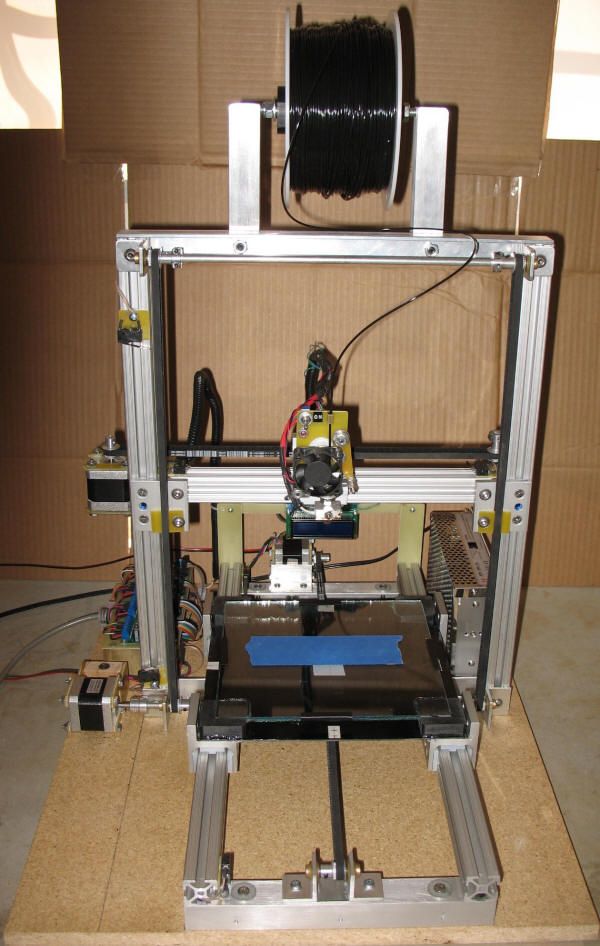

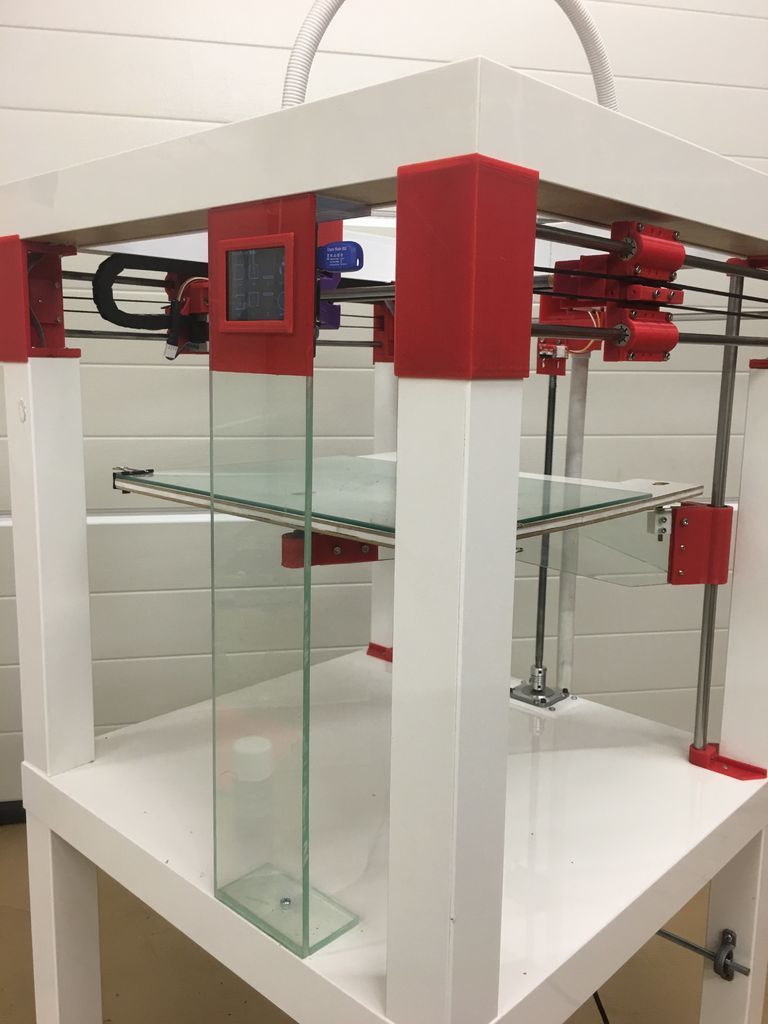

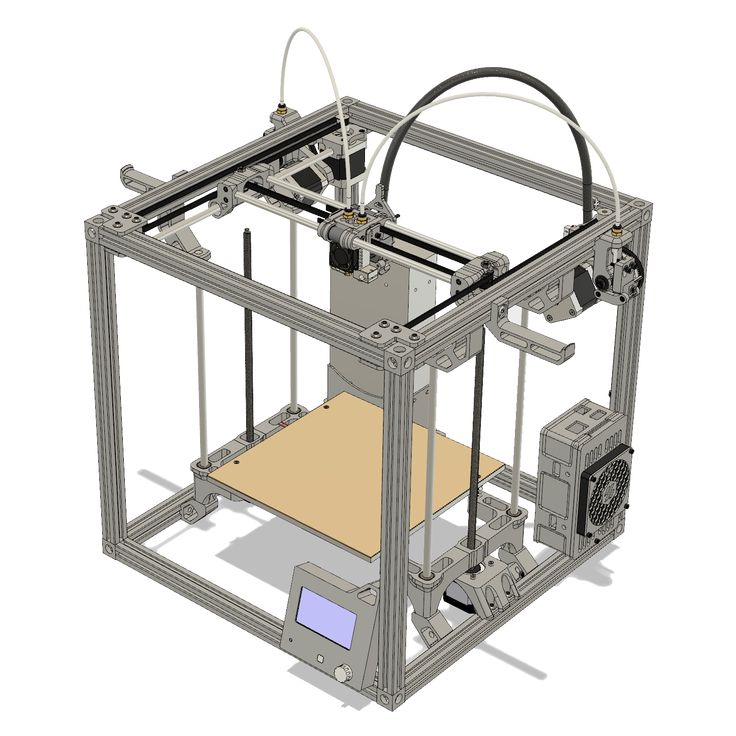

3D printing utilizing the extrusion of thermoplastic material is easily the most common — and recognizable — 3DP process. The most popular name for the process is Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM), due to its longevity, however this is a trade name, registered by Stratasys, the company that originally developed it. Stratasys’ FDM technology has been around since the early 1990’s and today is an industrial grade 3D printing process. However, the proliferation of entry-level 3D printers that have emerged since 2009 largely utilize a similar process, generally referred to as Freeform Fabrication (FFF), but in a more basic form due to patents still held by Stratasys. The earliest RepRap machines and all subsequent evolutions — open source and commercial — employ extrusion methodology. However, following Stratasys’ patent infringement filing against Afiniathere is a question mark over how the entry-level end of the market will develop now, with all of the machines potentially in Stratasys’ firing line for patent infringements.

However, the proliferation of entry-level 3D printers that have emerged since 2009 largely utilize a similar process, generally referred to as Freeform Fabrication (FFF), but in a more basic form due to patents still held by Stratasys. The earliest RepRap machines and all subsequent evolutions — open source and commercial — employ extrusion methodology. However, following Stratasys’ patent infringement filing against Afiniathere is a question mark over how the entry-level end of the market will develop now, with all of the machines potentially in Stratasys’ firing line for patent infringements.

The process works by melting plastic filament that is deposited, via a heated extruder, a layer at a time, onto a build platform according to the 3D data supplied to the printer. Each layer hardens as it is deposited and bonds to the previous layer.

Stratasys has developed a range of proprietary industrial grade materials for its FDM process that are suitable for some production applications. At the entry-level end of the market, materials are more limited, but the range is growing. The most common materials for entry-level FFF 3D printers are ABS and PLA.

At the entry-level end of the market, materials are more limited, but the range is growing. The most common materials for entry-level FFF 3D printers are ABS and PLA.

The FDM/FFF processes require support structures for any applications with overhanging geometries. For FDM, this entails a second, water-soluble material, which allows support structures to be relatively easily washed away, once the print is complete. Alternatively, breakaway support materials are also possible, which can be removed by manually snapping them off the part. Support structures, or lack thereof, have generally been a limitation of the entry level FFF 3D printers. However, as the systems have evolved and improved to incorporate dual extrusion heads, it has become less of an issue.

In terms of models produced, the FDM process from Stratasys is an accurate and reliable process that is relatively office/studio-friendly, although extensive post-processing can be required. At the entry-level, as would be expected, the FFF process produces much less accurate models, but things are constantly improving.

The process can be slow for some part geometries and layer-to-layer adhesion can be a problem, resulting in parts that are not watertight. Again, post-processing using Acetone can resolve these issues.

Inkjet

There are two 3D printing process that utilize a jetting technique.

Binder jetting: where the material being jetted is a binder, and is selectively sprayed into a powder bed of the part material to fuse it a layer at a time to create/print the required part. As is the case with other powder bed systems, once a layer is completed, the powder bed drops incrementally and a roller or blade smoothes the powder over the surface of the bed, prior to the next pass of the jet heads, with the binder for the subsequent layer to be formed and fused with the previous layer.

Advantages of this process, like with SLS, include the fact that the need for supports is negated because the powder bed itself provides this functionality. Furthermore, a range of different materials can be used, including ceramics and food. A further distinctive advantage of the process is the ability to easily add a full colour palette which can be added to the binder.

A further distinctive advantage of the process is the ability to easily add a full colour palette which can be added to the binder.

The parts resulting directly from the machine, however, are not as strong as with the sintering process and require post-processing to ensure durability.

Material jetting: a 3D printing process whereby the actual build materials (in liquid or molten state) are selectively jetted through multiple jet heads (with others simultaneously jetting support materials). However, the materials tend to be liquid photopolymers, which are cured with a pass of UV light as each layer is deposited.

The nature of this product allows for the simultaneous deposition of a range of materials, which means that a single part can be produced from multiple materials with different characteristics and properties. Material jetting is a very precise 3D printing method, producing accurate parts with a very smooth finish.

Selective Deposition Lamination (SDL)

SDL is a proprietary 3D printing process developed and manufactured by Mcor Technologies. There is a temptation to compare this process with the Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM) process developed by Helisys in the 1990’s due to similarities in layering and shaping paper to form the final part. However, that is where any similarity ends.

There is a temptation to compare this process with the Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM) process developed by Helisys in the 1990’s due to similarities in layering and shaping paper to form the final part. However, that is where any similarity ends.

The SDL 3D printing process builds parts layer by layer using standard copier paper. Each new layer is fixed to the previous layer using an adhesive, which is applied selectively according to the 3D data supplied to the machine. This means that a much higher density of adhesive is deposited in the area that will become the part, and a much lower density of adhesive is applied in the surrounding area that will serve as the support, ensuring relatively easy “weeding,” or support removal.

After a new sheet of paper is fed into the 3D printer from the paper feed mechanism and placed on top of the selectively applied adhesive on the previous layer, the build plate is moved up to a heat plate and pressure is applied. This pressure ensures a positive bond between the two sheets of paper. The build plate then returns to the build height where an adjustable Tungsten carbide blade cuts one sheet of paper at a time, tracing the object outline to create the edges of the part. When this cutting sequence is complete, the 3D printer deposits the next layer of adhesive and so on until the part is complete.

The build plate then returns to the build height where an adjustable Tungsten carbide blade cuts one sheet of paper at a time, tracing the object outline to create the edges of the part. When this cutting sequence is complete, the 3D printer deposits the next layer of adhesive and so on until the part is complete.

SDL is one of the very few 3D printing processes that can produce full colour 3D printed parts, using a CYMK colour palette. And because the parts are standard paper, which require no post-processing, they are wholly safe and eco-friendly. Where the process is not able to compete favourably with other 3D printing processes is in the production of complex geometries and the build size is limited to the size of the feedstock.

EBM

The Electron Beam Melting 3D printing technique is a proprietary process developed by Swedish company Arcam. This metal printing method is very similar to the Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) process in terms of the formation of parts from metal powder. The key difference is the heat source, which, as the name suggests is an electron beam, rather than a laser, which necessitates that the procedure is carried out under vacuum conditions.

The key difference is the heat source, which, as the name suggests is an electron beam, rather than a laser, which necessitates that the procedure is carried out under vacuum conditions.

EBM has the capability of creating fully-dense parts in a variety of metal alloys, even to medical grade, and as a result the technique has been particularly successful for a range of production applications in the medical industry, particularly for implants. However, other hi-tech sectors such as aerospace and automotive have also looked to EBM technology for manufacturing fulfillment.

05 - Materials

The materials available for 3D printing have come a long way since the early days of the technology. There is now a wide variety of different material types, that are supplied in different states (powder, filament, pellets, granules, resin etc).

Specific materials are now generally developed for specific platforms performing dedicated applications (an example would be the dental sector) with material properties that more precisely suit the application.

However, there are now way too many proprietary materials from the many different 3D printer vendors to cover them all here. Instead, this article will look at the most popular types of material in a more generic way. And also a couple of materials that stand out.

Plastics

Nylon, or Polyamide, is commonly used in powder form with the sintering process or in filament form with the FDM process. It is a strong, flexible and durable plastic material that has proved reliable for 3D printing. It is naturally white in colour but it can be coloured — pre- or post printing. This material can also be combined (in powder format) with powdered aluminium to produce another common 3D printing material for sintering — Alumide.

ABS is another common plastic used for 3D printing, and is widely used on the entry-level FDM 3D printers in filament form. It is a particularly strong plastic and comes in a wide range of colours. ABS can be bought in filament form from a number of non-propreitary sources, which is another reason why it is so popular.

PLA is a bio-degradable plastic material that has gained traction with 3D printing for this very reason. It can be utilized in resin format for DLP/SL processes as well as in filament form for the FDM process. It is offered in a variety of colours, including transparent, which has proven to be a useful option for some applications of 3D printing. However it is not as durable or as flexible as ABS.

LayWood is a specially developed 3D printing material for entry-level extrusion 3D printers. It comes in filament form and is a wood/polymer composite (also referred to as WPC).

Metals

A growing number of metals and metal composites are used for industrial grade 3D printing. Two of the most common are aluminium and cobalt derivatives.

One of the strongest and therefore most commonly used metals for 3D printing is Stainless Steel in powder form for the sintering/melting/EBM processes. It is naturally silver, but can be plated with other materials to give a gold or bronze effect.

In the last couple of years Gold and Silver have been added to the range of metal materials that can be 3D printed directly, with obvious applications across the jewellery sector. These are both very strong materials and are processed in powder form.

Titanium is one of the strongest possible metal materials and has been used for 3D printing industrial applications for some time. Supplied in powder form, it can be used for the sintering/melting/EBM processes.

Ceramics

Ceramics are a relatively new group of materials that can be used for 3D printing with various levels of success. The particular thing to note with these materials is that, post printing, the ceramic parts need to undergo the same processes as any ceramic part made using traditional methods of production — namely firing and glazing.

Paper

Standard A4 copier paper is a 3D printing material employed by the proprietary SDL process supplied by Mcor Technologies. The company operates a notably different business model to other 3D printing vendors, whereby the capital outlay for the machine is in the mid-range, but the emphasis is very much on an easily obtainable, cost-effective material supply, that can be bought locally. 3D printed models made with paper are safe, environmentally friendly, easily recyclable and require no post-processing.

The company operates a notably different business model to other 3D printing vendors, whereby the capital outlay for the machine is in the mid-range, but the emphasis is very much on an easily obtainable, cost-effective material supply, that can be bought locally. 3D printed models made with paper are safe, environmentally friendly, easily recyclable and require no post-processing.

Bio Materials

There is a huge amount of research being conducted into the potential of 3D printing bio materials for a host of medical (and other) applications. Living tissue is being investigated at a number of leading institutions with a view to developing applications that include printing human organs for transplant, as well as external tissues for replacement body parts. Other research in this area is focused on developing food stuffs — meat being the prime example.

Food

Experiments with extruders for 3D printing food substances has increased dramatically over the last couple of years. Chocolate is the most common (and desirable). There are also printers that work with sugar and some experiments with pasta and meat. Looking to the future, research is being undertaken, to utilize 3D printing technology to produce finely balanced whole meals.

Chocolate is the most common (and desirable). There are also printers that work with sugar and some experiments with pasta and meat. Looking to the future, research is being undertaken, to utilize 3D printing technology to produce finely balanced whole meals.

And finally, one company that does have a unique (proprietary) material offering is Stratasys, with its digital materials for the Objet Connex 3D printing platform. This offering means that standard Objet 3D printing materials can be combined during the printing process — in various and specified concentrations — to form new materials with the required properties. Up to 140 different Digital Materials can be realized from combining the existing primary materials in different ways.

06 - Global Effects

Global Effects on Manufacturing

3D printing is already having an effect on the way that products are manufactured – the nature of the technology permits new ways of thinking in terms of the social, economic,environmental and security implications of the manufacturing process with universally favourable results.

One of the key factors behind this statement is that 3D printing has the potential to bring production closer to the end user and/or the consumer, thereby reducing the current supply chain restrictions. The customisation value of 3D printing and the ability to produce small production batches on demand is a sure way to engage consumers AND reduce or negate inventories and stock piling — something similar to how Amazon operates its business.

Shipping spare parts and products from one part of the world to the other could potentially become obsolete, as the spare parts might possibly be 3D printed on site. This could have a major impact on how businesses large and small, the military and consumers operate and interact on a global scale in the future. The ultimate aim for many is for consumers to operate their own 3D printer at home, or within their community, whereby digital designs of any (customizable) product are available for download via the internet, and can be sent to the printer, which is loaded with the correct material(s). Currently, there is some debate about whether this will ever come to pass, and even more rigorous debate about the time frame in which it may occur.

Currently, there is some debate about whether this will ever come to pass, and even more rigorous debate about the time frame in which it may occur.

The wider adoption of 3D printing would likely cause re-invention of a number of already invented products, and, of course, an even bigger number of completely new products. Today previously impossible shapes and geometries can be created with a 3D printer, but the journey has really only just begun. 3D printing is believed by many to have very great potential to inject growth into innovation and bring back local manufacturing.

Potential Effects to the Global Economy

The use of 3D printing technology has potential effects on the global economy, if adopted world wide. The shift of production and distribution from the current model to a localized production based on-demand, on site, customized production model could potentially reduce the imbalance between export and import countries.

3D printing would have the potential to create new industries and completely new professions, such as those related to the production of 3D printers. There is an opportunity for professional services around 3D printing, ranging from new forms of product designers, printer operators, material suppliers all the way to intellectual property legal disputes and settlements. Piracy is a current concern related to 3D printing for many IP holders.

The effect of 3D printing on the developing world is a double-edged sword. One example of the positive effect is lowered manufacturing cost through recycled and other local materials, but the loss of manufacturing jobs could hit many developing countries severely, which would take time to overcome.

The developed world, would benefit perhaps the most from 3D printing, where the growing aged society and shift of age demographics has been a concern related to production and work force. Also the health benefits of the medical use of 3D printing would cater well for an aging western society.

07 - Benefits & Value

3D printing, whether at an industrial, local or personal level, brings a host of benefits that traditional methods of manufacture (or prototyping) simply cannot.

Customisation

3D printing processes allow for mass customisation — the ability to personalize products according to individual needs and requirements. Even within the same build chamber, the nature of 3D printing means that numerous products can be manufactured at the same time according to the end-users requirements at no additional process cost.

Complexity

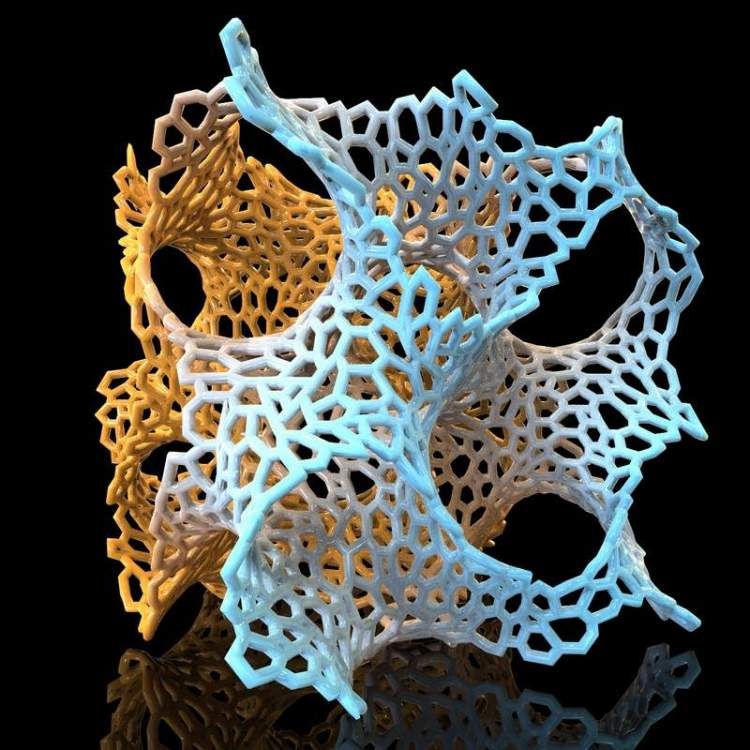

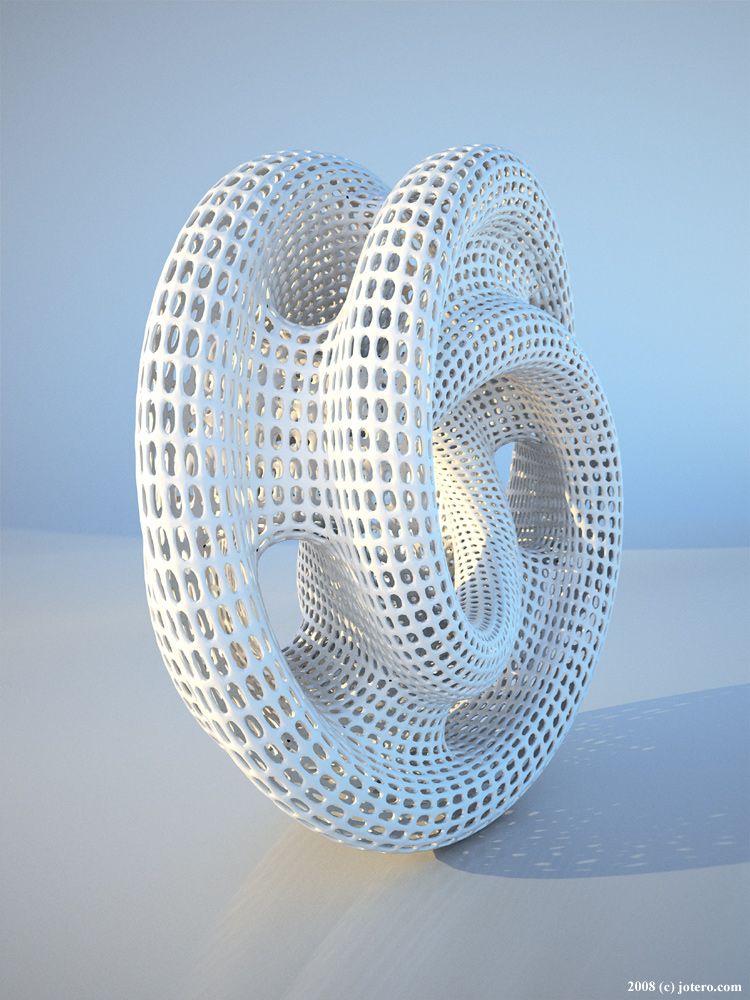

The advent of 3D printing has seen a proliferation of products (designed in digital environments), which involve levels of complexity that simply could not be produced physically in any other way. While this advantage has been taken up by designers and artists to impressive visual effect, it has also made a significant impact on industrial applications, whereby applications are being developed to materialize complex components that are proving to be both lighter and stronger than their predecessors. Notable uses are emerging in the aerospace sector where these issues are of primary importance.

Notable uses are emerging in the aerospace sector where these issues are of primary importance.

Tool-less

For industrial manufacturing, one of the most cost-, time- and labour-intensive stages of the product development process is the production of the tools. For low to medium volume applications, industrial 3D printing — or additive manufacturing — can eliminate the need for tool production and, therefore, the costs, lead times and labour associated with it. This is an extremely attractive proposition, that an increasing number or manufacturers are taking advantage of. Furthermore, because of the complexity advantages stated above, products and components can be designed specifically to avoid assembly requirements with intricate geometry and complex features further eliminating the labour and costs associated with assembly processes.

Sustainable / Environmentally Friendly

3D printing is also emerging as an energy-efficient technology that can provide environmental efficiencies in terms of both the manufacturing process itself, utilising up to 90% of standard materials, and, therefore, creating less waste, but also throughout an additively manufactured product’s operating life, by way of lighter and stronger design that imposes a reduced carbon footprint compared with traditionally manufactured products.

Furthermore, 3D printing is showing great promise in terms of fulfilling a local manufacturing model, whereby products are produced on demand in the place where they are needed — eliminating huge inventories and unsustainable logistics for shipping high volumes of products around the world.

08 - Applications

The origins of 3D printing in ‘Rapid Prototyping’ were founded on the principles of industrial prototyping as a means of speeding up the earliest stages of product development with a quick and straightforward way of producing prototypes that allows for multiple iterations of a product to arrive more quickly and efficiently at an optimum solution. This saves time and money at the outset of the entire product development process and ensures confidence ahead of production tooling.

Prototyping is still probably the largest, even though sometimes overlooked, application of 3D printing today.

The developments and improvements of the process and the materials, since the emergence of 3D printing for prototyping, saw the processes being taken up for applications further down the product development process chain. Tooling and casting applications were developed utilizing the advantages of the different processes. Again, these applications are increasingly being used and adopted across industrial sectors.

Tooling and casting applications were developed utilizing the advantages of the different processes. Again, these applications are increasingly being used and adopted across industrial sectors.

Similarly for final manufacturing operations, the improvements are continuing to facilitate uptake.

In terms of the industrial vertical markets that are benefitting greatly from industrial 3D printing across all of these broad spectrum applications, the following is a basic breakdown:

Medical and Dental

The medical sector is viewed as being one that was an early adopter of 3D printing, but also a sector with huge potential for growth, due to the customization and personalization capabilities of the technologies and the ability to improve people’s lives as the processes improve and materials are developed that meet medical grade standards.

3D printing technologies are being used for a host of different applications. In addition to making prototypes to support new product development for the medical and dental industries, the technologies are also utilized to make patterns for the downstream metal casting of dental crowns and in the manufacture of tools over which plastic is being vacuum formed to make dental aligners. The technology is also taken advantage of directly to manufacture both stock items, such as hip and knee implants, and bespoke patient-specific products, such as hearing aids, orthotic insoles for shoes, personalised prosthetics and one-off implants for patients suffering from diseases such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and cancer, along with accident and trauma victims. 3D printed surgical guides for specific operations are also an emerging application that is aiding surgeons in their work and patients in their recovery. Technology is also being developed for the 3D printing of skin, bone, tissue, pharmaceuticals and even human organs. However, these technologies remain largely decades away from commercialisation.

The technology is also taken advantage of directly to manufacture both stock items, such as hip and knee implants, and bespoke patient-specific products, such as hearing aids, orthotic insoles for shoes, personalised prosthetics and one-off implants for patients suffering from diseases such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and cancer, along with accident and trauma victims. 3D printed surgical guides for specific operations are also an emerging application that is aiding surgeons in their work and patients in their recovery. Technology is also being developed for the 3D printing of skin, bone, tissue, pharmaceuticals and even human organs. However, these technologies remain largely decades away from commercialisation.

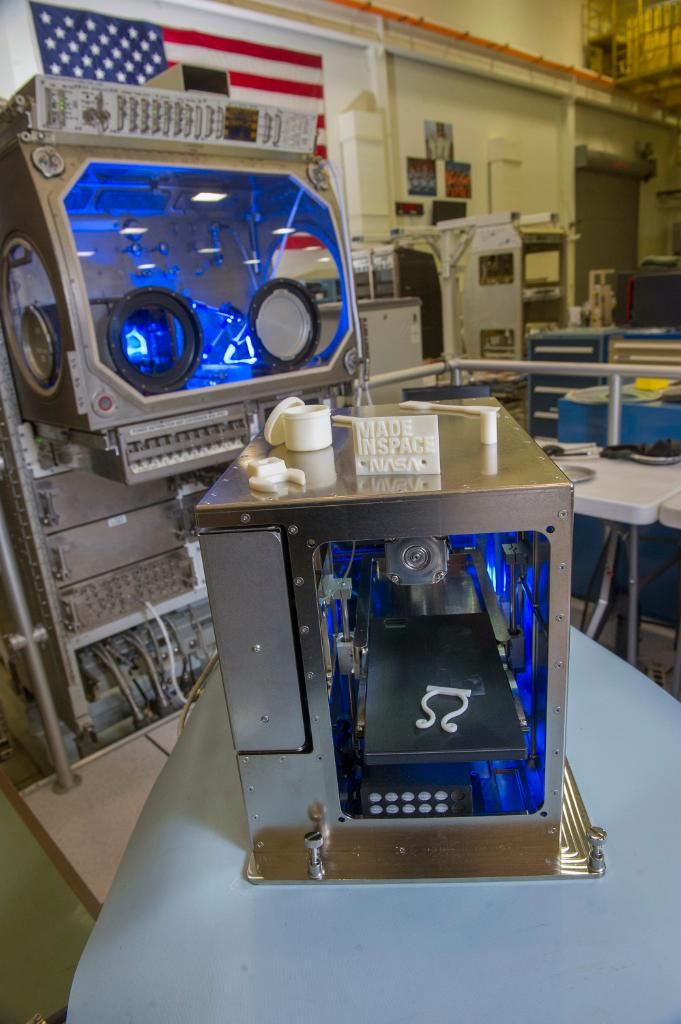

Aerospace

Like the medical sector, the aerospace sector was an early adopter of 3D printing technologies in their earliest forms for product development and prototyping. These companies, typically working in partnership with academic and research institutes, have been at the sharp end in terms or pushing the boundaries of the technologies for manufacturing applications.

Because of the critical nature of aircraft development, the R&D is demanding and strenuous, standards are critical and industrial grade 3D printing systems are put through their paces. Process and materials development have seen a number of key applications developed for the aerospace sector — and some non-critical parts are all-ready flying on aircraft.

High profile users include GE / Morris Technologies, Airbus / EADS, Rolls-Royce, BAE Systems and Boeing. While most of these companies do take a realistic approach in terms of what they are doing now with the technologies, and most of it is R&D, some do get quite bullish about the future.

Automotive

Another general early adopter of Rapid Prototying technologies — the earliest incarnation of 3D printing — was the automotive sector. Many automotive companies — particularly at the cutting edge of motor sport and F1 — have followed a similar trajectory to the aerospace companies. First (and still) using the technologies for prototyping applications, but developing and adapting their manufacturing processes to incorporate the benefits of improved materials and end results for automotive parts.

First (and still) using the technologies for prototyping applications, but developing and adapting their manufacturing processes to incorporate the benefits of improved materials and end results for automotive parts.

Many automotive companies are now also looking at the potential of 3D printing to fulfill after sales functions in terms of production of spare/replacement parts, on demand, rather than holding huge inventories.

Jewellery

Traditionally, the design and manufacturing process for jewellery has always required high levels of expertise and knowledge involving specific disciplines that include fabrication, mould-making, casting, electroplating, forging, silver/gold smithing, stone-cutting, engraving and polishing. Each of these disciplines has evolved over many years and each requires technical knowledge when applied to jewellery manufacture. Just one example is investment casting — the origins of which can be traced back more than 4000 years.

For the jewellery sector, 3D printing has proved to be particularly disruptive. There is a great deal of interest — and uptake — based on how 3D printing can, and will, contribute to the further development of this industry. From new design freedoms enabled by 3D CAD and 3D printing, through improving traditional processes for jewellery production all the way to direct 3D printed production eliminating many of the traditional steps, 3D printing has had — and continues to have — a tremendous impact in this sector.

There is a great deal of interest — and uptake — based on how 3D printing can, and will, contribute to the further development of this industry. From new design freedoms enabled by 3D CAD and 3D printing, through improving traditional processes for jewellery production all the way to direct 3D printed production eliminating many of the traditional steps, 3D printing has had — and continues to have — a tremendous impact in this sector.

Art / Design / Sculpture

Artists and Sculptors are engaging with 3D printing in myriad of different ways to explore form and function in ways previously impossible. Whether purely to find new original expression or to learn from old masters this is a highly charged sector that is increasingly finding new ways of working with 3D printing and introducing the results to the world. There are numerous artists that have now made a name for themselves by working specifically with 3D modelling, 3D scanning and 3D printing technologies.

- Joshua Harker

- Dizingof

- Jessica Rosenkrantz at Nervous System

- Pia Hinze

- Nick Ervinck

- Lionel Dean

- And many others.

The discipline of 3D scanning in conjunction with 3D printing also brings a new dimension to the art world, however, in that artists and students now have a proven methodology of reproducing the work of past masters and creating exact replicas of ancient (and more recent) sculptures for close study – works of art that they would otherwise never have been able to interact with in person. The work of Cosmo Wenman is particularly enlightening in this field.

Architecture

Architectural models have long been a staple application of 3D printing processes, for producing accurate demonstration models of an architect’s vision. 3D printing offers a relatively fast, easy and economically viable method of producing detailed models directly from 3D CAD, BIM or other digital data that architects use. Many successful architectural firms, now commonly use 3D printing (in house or as a service) as a critical part of their workflow for increased innovation and improved communication.

More recently some visionary architects are looking to 3D printing as a direct construction method. Research is being conducted at a number of organizations on this front, most notably Loughborough University, Contour Crafting and Universe Architecture.

Fashion

As 3D printing processes have improved in terms of resolution and more flexible materials, one industry, renowned for experimentation and outrageous statements, has come to the fore. We are of course talking about fashion!

3D printed accessories including shoes, head-pieces, hats and bags have all made their way on to global catwalks. And some even more visionary fashion designers have demonstrated the capabilities of the tech for haute couture — dresses, capes, full-length gowns and even some under wear have debuted at different fashion venues around the world.

Iris van Herpen should get a special mention as the leading pioneer in this vein. She has produced a number of collections — modelled on the catwalks of Paris and Milan — that incorporate 3D printing to blow up the ‘normal rules’ that no longer apply to fashion design. Many have followed, and continue to follow, in her footsteps, often with wholly original results.

Many have followed, and continue to follow, in her footsteps, often with wholly original results.

Although a late-comer to the 3D printing party, food is one emerging application (and/or 3D printing material) that is getting people very excited and has the potential to truly take the technology into the mainstream. After all, we will all, always, need to eat! 3D printing is emerging as a new way of preparing and presenting food.

Initial forays into 3D printing food were with chocolate and sugar, and these developments have continued apace with specific 3D printers hitting the market. Some other early experiments with food including the 3D printing of “meat” at the cellular protein level. More recently pasta is another food group that is being researched for 3D printing food.

Looking to the future 3D printing is also being considered as a complete food preparation method and a way of balancing nutrients in a comprehensive and healthy way.

Consumers

The holy grail for 3D printing vendors is consumer 3D printing. There is a widespread debate as to whether this is a feasible future. Currently, consumer uptake is low due to the accessibility issues that exist with entry level (consumer machines). There is headway being made in this direction by the larger 3D printing companies such as 3D Systems and Makerbot, as a subsidiary of Stratasys as they try to make the 3D printing process and the ancillary components (software, digital content etc) more accessible and user-friendly. There are currently three main ways that the person on the street can interact with 3D printing tech for consumer products:

There is a widespread debate as to whether this is a feasible future. Currently, consumer uptake is low due to the accessibility issues that exist with entry level (consumer machines). There is headway being made in this direction by the larger 3D printing companies such as 3D Systems and Makerbot, as a subsidiary of Stratasys as they try to make the 3D printing process and the ancillary components (software, digital content etc) more accessible and user-friendly. There are currently three main ways that the person on the street can interact with 3D printing tech for consumer products:

- design + print

- choose + print

- choose + 3D printing service fulfillment

09 - Glossary

3DP 3D Printing

ABS Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene

AM Additive Manufacturing

CAD / CAM Computer-aided design / Computer-aided manufacturing

CAE Computer-aided engineering

DLP Digital Light Processing

DMD Direct Metal Deposition

DMLS Direct Metal Laser Sintering

EBM Electron Beam Melting

EVA Ethylene Vinyl Acetate

FDM Fused Deposition Modelling (Trademark of Stratasys)

FFF Freeform Fabrication

LENS Laser Engineering Net-Shaping (Trademark of SNL, licensed to Optomec)

LS Laser Sintering

PLA Polylactic Acid

RE Reverse Engineering

RM Rapid Manufacturing

RP Rapid Prototyping

RT Rapid Tooling

SL Stereolithography

SLA Stereolithography Apparatus (Registered Trademark of 3D Systems)

SLM Selective Laser Melting

SLS Selective Laser Sintering (Registered Trademark of 3D Systems)

STL / . stl Stereo Lithograpic

stl Stereo Lithograpic

How Do You Make & Create STL Files for 3D Printing – Simple Guide – 3D Printerly

When you are in the field of 3D printing, there are steps you have to follow to be able to actually 3D print your objects. Many steps are done for you but making 3D printer files is one of the most important ones.

This article will show you exactly how 3D printer files are made so read on if you’d like to know.

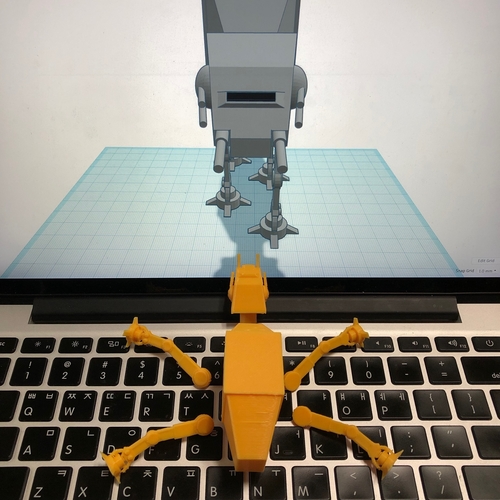

3D printer files are made by using Computer Aided Model (CAD) software which allows you to create what your model will look like. After your model is complete, you need to ‘slice’ your CAD file in a slicer program, the most popular being Cura. After your model is sliced, it will be ready for 3D printing.

Once you understand the steps of this process and do it for yourself, it all becomes very easy and clear. I will do my best to detail the step-by-step process on how beginners create 3D printer files.

Creating models for 3D printing and learning how to make your own 3D model is a great skill to learn, so let’s get right into it.

- Choose & open a CAD program

- Create a design or model using the tools in your chosen program

- Save & export your completed design to your computer (STL file)

- Choose a slicer program – Cura for beginners

- Open & ‘Slice’ your file with your desired settings into a G-Code File

Choose & Open a CAD Program

There are many CAD programs out there that can be used to create your model, but some are definitely more tiered towards beginners which is what I’ll focus on in this article.

Also, many higher level programs actually need to be purchased, so you’ll be happy to know everything I recommend will be completely free.

The best CAD programs for beginners are:

- TinkerCAD – click and create your own account

- Blender

- Fusion 360

- Sketch Up

- FreeCAD

- Onshape

Check out my article Best Free 3D Printing Software – CAD, Slicers & More.

The one that I will focus on and do recommend is TinkerCAD for beginners because it was definitely designed for you guys in mind. Beginners don’t want a complicated CAD program that takes a while getting used to, they want to be able to put something together in the first 5 minutes and see its capabilities.

One of the great features of TinkerCAD is the fact that it’s browser-based so you don’t have to install some huge program file to get started. Just go to TinkerCAD, create an account, go through the short tutorial on the platform and get to modeling.

Once you get the hang of one CAD program and the way designing a model works, you can move onto other programs, but at first just stick to one simple program.

TinkerCAD has enough capabilities to keep you modeling there for at least a few months, before you think about moving to a software with more features. For now, it will work wonders!

Create A Design Using the Tools in Your Chosen Program

TinkerCAD specializes in ease of use, as you put together blocks and shapes to gradually build a more complex structure that you can be proud of. The video below will show you a quick tutorial on exactly how it looks and how it’s done.

The video below will show you a quick tutorial on exactly how it looks and how it’s done.

It’s always best to follow a video tutorial when learning how to create designs, while doing the same thing in the program yourself.

Reading a guide of some sort is great when you understand the program and are looking for ways to do cool, new things but when just starting out, get the experience behind you.

Once you’ve created some of your own models by following a tutorial, a good point to go to next is to play around in the program and get creative. One thing I chose to do is find a few household objects and try to model it as best as I could.

This ranged from cups, bottles, small boxes, vitamin containers, anything really. If you want to get really accurate, you can get a sweet pair of Calipers from Amazon.

If you want to get really accurate, you can get a sweet pair of Calipers from Amazon.

If you want a quick, cheap but reliable set I’d recommend the Sangabery Digital Caliper.

It has four measuring modes, two unit conversion & zero setting function. You can get very accurate readings with this device, so I do recommend you getting one if you don’t already. Also comes with two spare batteries!

If you want a higher quality Caliper, go for the Rexbeti Stainless Steel Digital Caliper. It is more premium with a polished finish and a case to hold the device. It comes with IP54 water & dust protection, has 0.02mm accuracy and is great for the long-run.

Once you get some good practice creating different items, you’ll be a lot more prepared to start making useful and complex 3D printer files.

At first, it seems like all these simple shapes and holes won’t be able to make much. This is what I thought at first before seeing what people could really create in this software.

The following was made on TinkerCAD by Delta666 found on MyMiniFactory. It would be hard to describe this as a simple design, which just goes to show you the potential you could have with designing your own 3D printer files.

Save & Export Your Completed Design to Your Computer (STL File)

The great thing about TinkerCAD is how it’s made for things to be easy to use. This also includes saving and exporting your STL files straight to your computer.

Unlike some downloaded CAD software, this one auto-saves your work each change you make so you don’t have to worry about losing your work.

As long as you have named your work in the top left, it should continue to save. You’ll see a small message saying ‘All Changes Saved’ so you know if it’s working.

As you can see in the picture, exporting your CAD files into a downloadable STL file is a piece of cake. Simply click the ‘Export’ button in the top right of your TinkerCAD page and a box will pop up with a few options.

When it comes to 3D printing files, the most common ones we see are the .STL files. There are a few things that people say it’s abbreviated from such as Stereolithography, Standard Triangle Language and Standard Tessellation Language. Either way, we just know it works pretty good!

The complex part behind STL files is that they are made up of several tiny triangles, with more detailed parts having more triangles. The reason behind this is 3D printers can better understand this information with this simple geometric shape.

Below is a clear illustration of these triangles making up a model.

Choose a Slicer Program – Cura for Beginners

If you’re in the 3D printing field, you either would have come across Cura by Ultimaker or are already well-versed in the program. Cura is the most popular, cross-platform slicing software that 3D printer hobbyists use to prepare their files for 3D printing.

There isn’t much point trying to go with another slicer because this one works so well and does exactly what you need it to do. It’s very beginner-friendly and doesn’t take long at all to get the hang of it.

It’s very beginner-friendly and doesn’t take long at all to get the hang of it.

There are other slicer programs out there, some even dedicated to specific 3D printers like PrusaSlicer or ChiTuBox. They all essentially do the same thing but Cura is the choice I recommend.

Check out my article Best Slicer for the Ender 3 (Pro/V2/S1), which also goes for other 3D printers as well.

Open & ‘Slice’ Your File With Your Desired Settings Into a G-Code File

The term ‘slice’ your file is one that is widely used in the 3D printing field which means to prepare your CAD model and turn it into a G-code file which 3D printers can make use of.

G-code is basically a series of commands that tell your 3D printer what to do, from movement, to temperatures, to fan speed.

When you slice your file, there is a certain function where you can preview your model in its 3D printing form. This is where you view each layer of your 3D print from the ground, up and you can even see the direction your print head will go while in the printing process.

It really isn’t as complicated as it looks. All it really takes is looking over the settings and hitting the blue ‘Slice’ button on the bottom right of the program. The box to the top right shows a simplified way to change settings without getting into all the specific settings.

It’s a spice rack in case you’re wondering!There are many settings in your slicer you can take control of such as:

- Print speed

- Nozzle temperature

- Bed temperature

- Retraction settings

- Print order prioritization

- Cooling fan settings

- Infill percentage

- Infill pattern

Now just because it isn’t complicated to get started doesn’t it mean it can’t get as complicated as you’d like it. I’m sure there are settings that Cura experts have never thought about touching.

This really is a short list when you have seen just how many settings there are, but luckily, you don’t have to worry about most of the settings. Cura has default ‘profiles’ which give you a list of already done for you settings that you can input.

This profile usually works great by itself, but it can take a little tweaking on the nozzle & bed temperature before you get some great prints.

There is a cool menu which allows users to choose custom setting views for beginners to masters, down to custom so the functionality and ease of use is great.

After you follow all these steps, you’ll have created your 3D printer file which your printer can understand. Once I’ve sliced a model, I simply get my USB drive and micro SD card which came with my Ender 3, plug it into my laptop and select the ‘Save to Removable Device’ button and Voilà!

I hope these steps were easy to follow and help you get started making your own 3D printer files.

It’s an amazing skill being able to design your own objects from start to finish, so try your best to stick with it and become an expert in the future.

If you found this helpful, I have other similar posts like the 25 Best 3D Printer Upgrades/Improvements You Can Get Done & 8 Ways How to Speed Up Your 3D Printer Without Losing Quality so feel free to check them out and happy printing!

All about 3D printing.

additive manufacturing. Basic concepts.

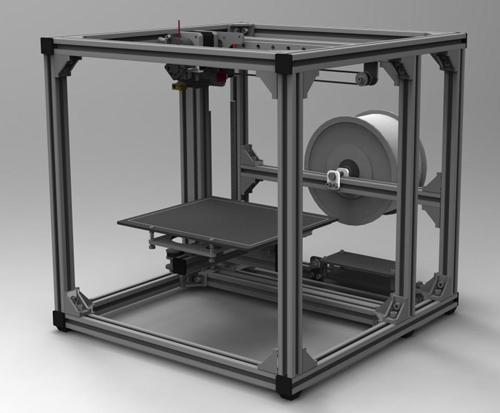

additive manufacturing. Basic concepts. - 1 Technology

- 2 Terminology

- 3 Fundamentals

- 4 Printing Technologies

- 5 3D printers

- 6 Application

- 7 Domestic and hobby use

- 8 Clothing

- 9 3D bioprinting

- 10 3D printing of implants and medical devices

- 11 3D printing services

- 12 Research into new applications

- 13 Intellectual Property

- 14 Influence of 3D printing

- 15 Space research

- 16 Social change

- 17 Firearms

Technology

Charles Hull - the father of modern 3D printing

3D printing is based on the concept of building an object in successive layers that display the contours of the model. In fact, 3D printing is the complete opposite of traditional mechanical production and processing methods such as milling or cutting, where the appearance of the product is formed by removing excess material (so-called "subtractive manufacturing").

In fact, 3D printing is the complete opposite of traditional mechanical production and processing methods such as milling or cutting, where the appearance of the product is formed by removing excess material (so-called "subtractive manufacturing").

3D printers are computer-controlled machines that build parts in an additive way. Although 3D printing technology appeared in the 80s of the last century, 3D printers were widely used commercially only in the early 2010s. The first viable 3D printer was created by Charles Hull, one of the founders of 3D Systems Corporation. At the beginning of the 21st century, there was a significant increase in sales, which led to a sharp drop in the cost of devices. According to the consulting firm Wohlers Associates, the global market for 3D printers and related services reached $2.2 billion in 2012, growing by 29%.% compared to 2011.

3D printing technologies are used for prototyping and distributed manufacturing in architecture, construction, industrial design, automotive, aerospace, military, engineering and medical industries, bioengineering (to create artificial fabrics), fashion and footwear, jewelry, in education, geographic information systems, food industry and many other areas. According to research, open source home 3D printers will allow you to win back the capital cost of your own purchase through the economy of household production of items.

According to research, open source home 3D printers will allow you to win back the capital cost of your own purchase through the economy of household production of items.

Terminology

Additive manufacturing involves the construction of objects by adding the necessary material, and not by removing excess, as is the case with subtractive methods

The term "additive manufacturing" refers to the technology of creating objects by applying successive layers material. Models made using the additive method can be used at any stage of production - both for the production of prototypes (so-called rapid prototyping) and as finished products themselves (so-called rapid production).