3D printed prosthetic cat leg

Pet Prosthetics Get a Boost From 3D Printing

Boone Ashworth

Gear

New modeling software is helping animal health experts develop more customizable prosthetics for pets with missing limbs. Still, not all legs are created equal.

Photograph: Dive Design

Consider the three-legged dog. Maybe you own one, or have seen them in the park or in any of the billions of Dodo videos about them. Lopsided yet resilient, they evoke a kind of fawning sympathy from us humans that’s unmatched by the typical quadruped canine.

“People are drawn to specially abled pets,” says Rene Agredano, a cofounder of the pet-amputation support website Tripawds. “I think the attraction is that we just want to help them. We just want to make sure that they are given an equal chance at having a happy life. ”

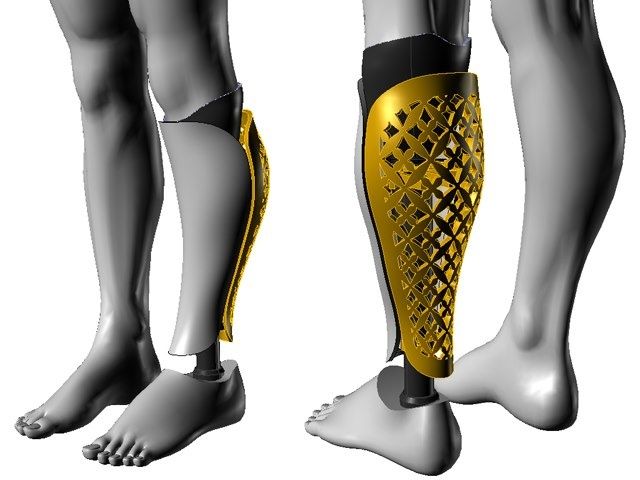

More and more, that desire to help manifests as prosthetics, especially in cases where the animal has lost more than one limb. Pets with artificial limbs have become a whole genre of feel-good videos of their own. A cat with bionic hind legs. A tortoise with wheels. The clips make the rounds on Facebook, where they add a smidge of feel-good optimism to the otherwise dour deluge that is your newsfeed. 3D printing has propelled the industry forward. Printed prosthetics can be lightweight, affordable-ish, and infinitely customizable. Doctors craft beaks for birds. High school students build artificial dog legs in their free time.

But not all pet prosthetics are created equal. And some veterinarians and people in the tripod community worry that the proliferation of easily craftable attachments could lead to unintended consequences for the critters that wear them.

Walking Distance

Dogs can lose a limb for a variety of reasons. Maybe they were born with an abnormal limb, or were hit by a car, or developed a cancerous growth that necessitated an amputation. A common quip among tripod lovers is that “dogs have three legs and a spare.” It’s true, to a point. Dogs adapt remarkably well to losing a limb, says Theresa Wendland, who specializes in animal sports medicine and rehabilitation at the Colorado Veterinary Specialist Group. But complications can arise as the animal compensates for what’s missing. In older dogs and dogs with arthritis or other mobility issues, putting extra weight on the remaining limbs can be a big problem.

A common quip among tripod lovers is that “dogs have three legs and a spare.” It’s true, to a point. Dogs adapt remarkably well to losing a limb, says Theresa Wendland, who specializes in animal sports medicine and rehabilitation at the Colorado Veterinary Specialist Group. But complications can arise as the animal compensates for what’s missing. In older dogs and dogs with arthritis or other mobility issues, putting extra weight on the remaining limbs can be a big problem.

Photograph: Dive Design

Photograph: Dive Design

“It really impacts their spinal mobility,” Wendland says. “They have to change the range of motion in their other limbs. They have to pull themselves forward in ways that are very unnatural.”

Prosthetics, if made right, can restore that range of motion. But as heart melting as it is to see a three-legged dog return to running on four legs, it’s not easy to build a proper puppy peg leg. Wendland, who works with the orthopedic and prosthetic company OrthoPets to help dogs adapt to their new limbs, says that it’s an involved process that takes time and technical know-how.

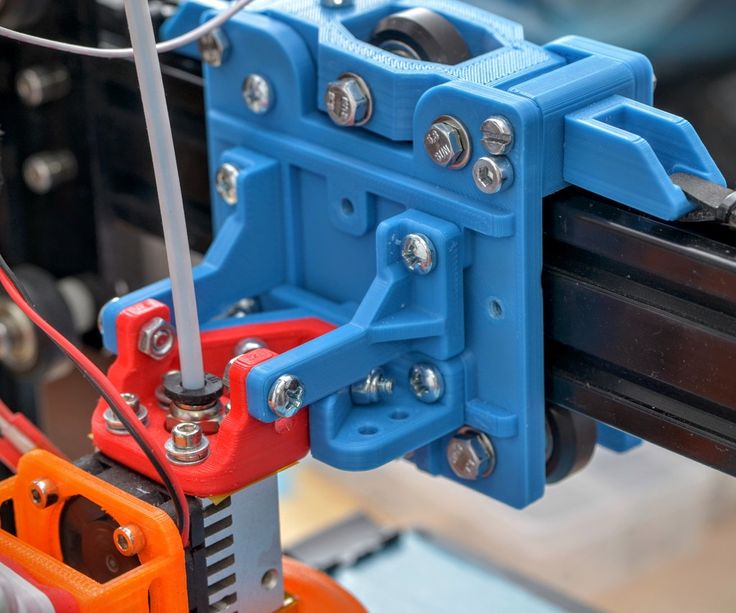

As with human prosthetics, an animal prosthetic has to be individually tailored to the build of the wearer. That means factoring in the animal's size, weight, height, stance, and gait. (A kit for a doberman won’t fit on a dachshund.) To do that, orthopedists have to study the animal’s movements and try to mold a limb that will sync up with the others. While techniques vary, a standard process is to make a plaster cast, design the prosthetic based on photos and video, then build it out with durable thermoplastics and metal. From there, they tweak the finer details by hand until it works with the animal. The process can take weeks.

Most Popular

There’s also the matter of the amount of the limb that needs replacing. The ideal spot to put a prosthetic, Wendland says, is as low on the limb as you can go. But if the whole limb is gone and there’s no obvious point to attach a prosthetic, it gets much trickier.

A Leg Up

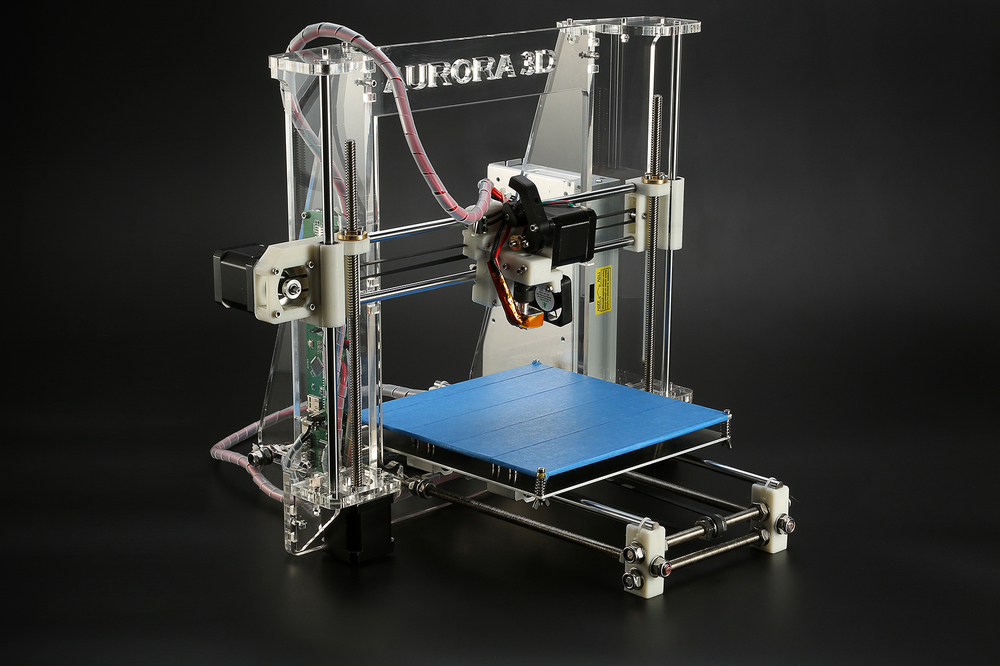

3D printing has long been hailed as a manufacturing revolution in many industries, prosthetics among them. And now, a New Jersey–based design firm called Dive Design thinks it’s the solution to full-limb replacement. It has partnered with a company called Bionic Pets that builds exactly what its name implies: accessibility tech for pets. Derrick Campana, who runs Bionic Pets, has long built pet prosthetics by hand. (He’s even got a show about it called The Wizard of Paws, which airs on Brigham Young University's television channel.) About a year ago, he invited Dive Design heads Alex Tholl and Adam Hecht to his lab in Virginia to look at how he could improve the process.

And now, a New Jersey–based design firm called Dive Design thinks it’s the solution to full-limb replacement. It has partnered with a company called Bionic Pets that builds exactly what its name implies: accessibility tech for pets. Derrick Campana, who runs Bionic Pets, has long built pet prosthetics by hand. (He’s even got a show about it called The Wizard of Paws, which airs on Brigham Young University's television channel.) About a year ago, he invited Dive Design heads Alex Tholl and Adam Hecht to his lab in Virginia to look at how he could improve the process.

“Something that kept coming up was the need for full limb prosthesis development,” Tholl says. The limbs that Campana had been building used too many resources and required too much labor to be manageable. Plus, Tholl says, “With the waste that was involved, it just didn’t make financial sense. For us, that’s when the wheels started turning.”

The first step was to find the right software to build the 3D models. Dive Design's intern, Julio Aira IV, a mechanical and biomedical engineering student at Penn State, had a student license to a modeling program developed by a company called nTopology. The others at Dive Design piggybacked off that pseudo-bootlegged software and went to work. (Their software licenses are now up to date.) The nTop Platform lets users build 3D models and simulate how they might function in the real world. That means designers can stress test and map movements of the limb before ever printing it out. The software is not limited to cute animal projects; the government defense contractor Lockheed Martin is an investor, and nTopology has designed optical components for defense tech companies like Raytheon as well. (The intricate jackets that fit the prosthetic to the dog's body were designed and customized with another 3D design company called Landau Design+Technology.)

Dive Design's intern, Julio Aira IV, a mechanical and biomedical engineering student at Penn State, had a student license to a modeling program developed by a company called nTopology. The others at Dive Design piggybacked off that pseudo-bootlegged software and went to work. (Their software licenses are now up to date.) The nTop Platform lets users build 3D models and simulate how they might function in the real world. That means designers can stress test and map movements of the limb before ever printing it out. The software is not limited to cute animal projects; the government defense contractor Lockheed Martin is an investor, and nTopology has designed optical components for defense tech companies like Raytheon as well. (The intricate jackets that fit the prosthetic to the dog's body were designed and customized with another 3D design company called Landau Design+Technology.)

Photograph: Dive Design

Most Popular

“The biggest thing is iterating,” Hecht says. “When you're doing something new, you never have the perfect idea immediately. It's always a lot of trial and error. So the faster we can go through the process of creating things and testing things in the real world, the better solution we’re going to have.”

“When you're doing something new, you never have the perfect idea immediately. It's always a lot of trial and error. So the faster we can go through the process of creating things and testing things in the real world, the better solution we’re going to have.”

Dive Design’s process is similar to building standard orthopedics: Study the dog, take measurements, model it out, and then build from there. But 3D printing lets the engineers quickly adapt and change the physical product in ways that are far less feasible with traditional prosthetics. If a particular joint or lattice that makes up a support isn’t working, they can rework it in a matter of hours.

Bionic Pets' Campana says the rapid iteration afforded by 3D printing is especially beneficial for younger animals, since the patient may need many devices as its body grows. "A new device may be needed, but we do not need to make a cast or redesign," he says in an email. "We can just resize the file and reprint."

“I’m kind of borderline obsessed with this kind of work,” Aira, who works on modeling and developing the prosthetics, says. “We’re really just scratching the surface of how we think about 3D printing and how we think about everything around us. It’s really amazing what we’re going to be able to do and how we’re going to be able to take advantage of these technologies.”

“We’re really just scratching the surface of how we think about 3D printing and how we think about everything around us. It’s really amazing what we’re going to be able to do and how we’re going to be able to take advantage of these technologies.”

Hit a Stride

While that enthusiasm may be in high supply, labor and expertise doesn’t come cheap. Wendland says the prosthetics on which she’s consulted typically fall somewhere between $1,800 to $2,000. Bionic Pets’ prices are still expensive, but more reasonable: $850 for a partial limb and $1,750 for a full limb. These hefty price tags may be familiar to pet owners who have experienced the sticker shock of an astronomical vet bill. So the ability to make inexpensive prosthetics is no doubt appealing.

Photograph: Dive Design

Most Popular

Wendland says she’s had people reach out to her who want to 3D print DIY prosthetics for their own dog, or for a school project. But the kind of materials people are able to utilize in their home printer likely aren’t going to meet the same standards as something that is professionally made.

But the kind of materials people are able to utilize in their home printer likely aren’t going to meet the same standards as something that is professionally made.

“What makes me a little nervous about 3D printing is that people start to get this idea that anybody can make a prosthetic,” Wendland says. “I just see potential for harm with something like that. I love that people are excited about it and that they want to help, but there’s a lot that has gone into the training and the people who are actually doing this for a living and making this happen in a functional way.”

Photograph: Dive Design

An animal might look cute with its artificial limb in an Instagram video, but if that prosthetic hasn’t been carefully crafted by people with the orthopedic knowledge to properly customize it, there’s a risk of it causing more harm than if there was no prosthetic at all. Let’s say a dog moves with the assistance of a wheeled cart. If the wheels are placed too far back, it can create excess stress on the spine. Place them too far forward, and the dog’s constantly tipping over onto its face. A leg prosthetic that doesn’t fit properly can cause sores and ulcerations where the bone meets the skin, sometimes resulting in internal damage in the leg.

Place them too far forward, and the dog’s constantly tipping over onto its face. A leg prosthetic that doesn’t fit properly can cause sores and ulcerations where the bone meets the skin, sometimes resulting in internal damage in the leg.

Prosthetic builders like Dive Design, Bionic Pets, and Ortho Pets have to work in close consultation with orthopedic veterinarians to ensure that their creations aren’t actively detrimental to the animal. Pet prosthetics are a new enough phenomenon that there isn’t a lot of research to definitively show what works and what doesn’t. For now, orthopedic surgeons and builders just have to rely on clinical experience.

Regardless of the type of prosthetic, one thing the animal can't avoid is the need for rehabilitation. It can take weeks or months of physical rehab for a dog to become comfortable with a prosthetic. That means more vet visits, more investment and expenses.

Wendland hasn’t worked with Dive Design’s models specifically, but she says these types of full-limb assistive devices have their place. But it’s important for every pet owner who finds themselves considering one to know their options.

But it’s important for every pet owner who finds themselves considering one to know their options.

“Depending on the situation, I almost wonder if that money wouldn't be a little bit better spent towards good rehabilitation,” Wendland says. “Maybe acupuncture for secondary muscle soreness, things like that, to keep a dog mobile. But I would absolutely consider these for a dog where they have problems with the other leg. I think this is a great use of 3D printing.”

Correction Dec. 21, 9:00 a.m: Updated language to clarify the difference between nTopology and its software. The company is nTopology and the software is nTop Platform. Also clarified the role of Landau Design+Technology, who worked to design and customize the prosthetic jackets.

More Great WIRED Stories

📩 Want the latest on tech, science, and more? Sign up for our newsletters!

Get rich selling used fashion online—or cry trying

The 8 best books about artificial intelligence to read now

Hold everything: Stormtroopers have discovered tactics

I tested positive for Covid-19.

What does that really mean?

What does that really mean?Gift ideas for people who just need a good night’s sleep

🎮 WIRED Games: Get the latest tips, reviews, and more

🏃🏽♀️ Want the best tools to get healthy? Check out our Gear team’s picks for the best fitness trackers, running gear (including shoes and socks), and best headphones

Boone Ashworth is a staff writer on the WIRED Gear desk, where he also produces the weekly Gadget Lab podcast. He graduated from San Francisco State University and still lives in the city. Currently, he has opened too many browser tabs.

Topics3-D printingdogsrobotics

More from WIREDNebraska Engineering students craft prosthetic for cat | Nebraska Today

Olive may have nine lives, but she had just three legs.

Until the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Abby Smith, Harrison Grasso and three fellow seniors in biological systems engineering put in the legwork that gave her another to stand on, that is.

With the help of a 3D printer at Nebraska Innovation Studio, the Husker engineering students recently finished fabricating a prosthetic leg prototype for Olive, a young tabby cat missing the lower half of her left foreleg.

“Olive was delightful,” said Grasso, a Lincoln native who will earn his degree in December.

“She’s a wonderful cat,” agreed Smith, who came to Lincoln from Kansas City and graduated in May. “I think most of our group was more dog people. We’re like, ‘Oh, we’re gonna be working with a cat…’ But Olive was a trooper throughout the entire process.”

The prosthetic was the culmination of joint capstone courses — Biological Systems Engineering 470 and BSEN 480 — that have seniors put to use, and put to the test, much of what they’ve learned in their previous three years. At the start of the fall 2020 semester, the BSEN 470 students completed a survey of their career goals and engineering interests. Following that survey, Smith and Grasso found themselves teamed with Jaden Schovanec, Rachael Stanek and Alexandra Jensen.

Among their mutual interests? Prosthetics. So instructor Deepak Keshwani assigned them a project conceived by Beth Galles, who has seen her share of three-legged cats — often the result of amputation following frostbite — as an assistant professor of practice with the Professional Program in Veterinary Medicine.

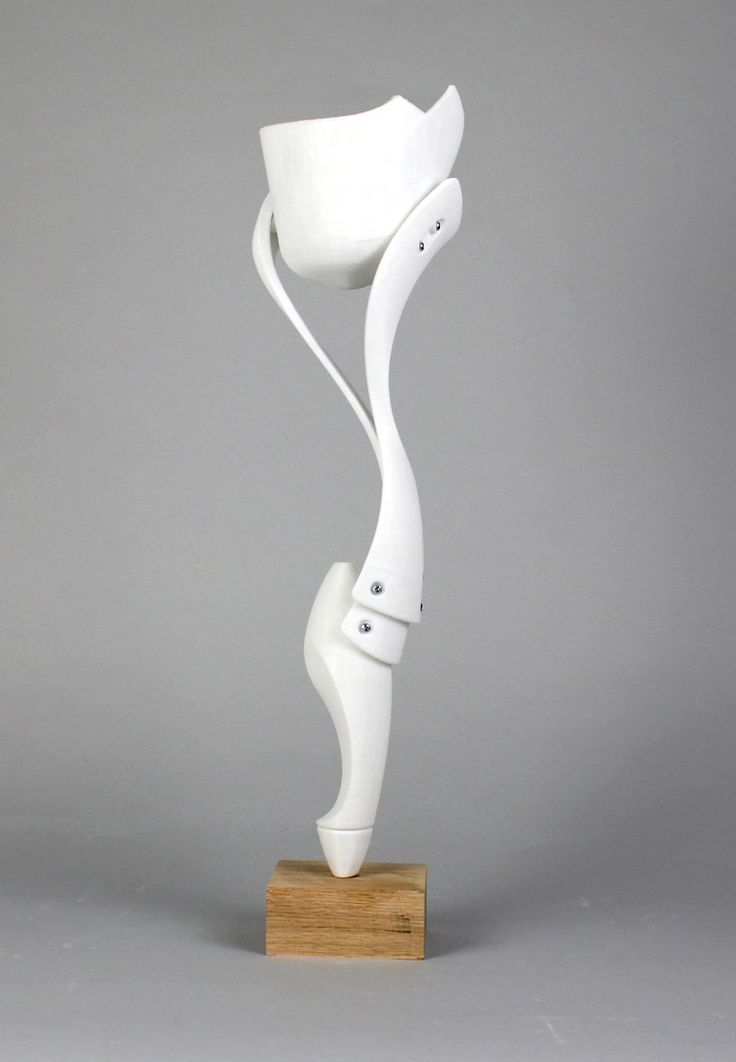

The team’s charge: Design and create a prosthetic that was adjustable, removable, non-toxic and cost less than $100 to produce. Over the next few months, the engineers would cycle through multiple iterations of their initial design, refining and simplifying it. They settled on a two-piece prototype made primarily of polylactic acid — a generic, cheaply printable material — and a sturdy proprietary plastic.

The bottom component of the prototype ends in a short, curved base that acts as a foot and is lined with synthetic rubber, lending it traction. The top portion is a three-walled, open-faced sheath, ending in a cup that houses the nub of the amputated leg. Securing that piece to the leg proved more than a little difficult, even after incorporating Velcro straps and a silicone sleeve for exactly that purpose.

“That was one of the biggest problems we encountered, was keeping this thing on,” Smith said of the prototype, which the team found it could build for about $10. “(Olive) had very slick fur and a lot of loose skin at the end of the amputation site. The silicone sleeve that we put directly on her was key in helping the prosthetic stay on.”

Actually placing the prosthetic on Olive was hardly easy, either, though Smith credited the patience and problem-solving of Galles and her veterinary colleagues with easing the process as much as possible. In the end, the team gave Schovanec the honors.

“Someone in his family has a cat, so we all volunteered him as the person to do that,” Grasso said with a grin. “He seemed the most qualified.”

As good-natured as Olive is, Smith said, she is still a cat. Her initial, natural response to being fitted with the prosthetic was to shake a leg in an effort to rid herself of the technology that the team had spent so many hours crafting.

“Out of all the senior design projects, I guess (Olive) was the one client who was actively working to make sure our design didn’t work,” said Grasso. “Once we got past finding a way to actually secure it to the leg, she was obviously hesitant to use it, just because she functioned pretty well without it.”

Yet she was, ultimately if gingerly, willing to put prosthetic foot to ground. Later, Olive trusted the prototype enough to put some weight on it while taking steps. By the third round of testing, she was even comfortable enough to engage in a signature housecat activity that her three-legged self was usually too hesitant to try: jumping off and onto ledges.

As their senior design project, @UNLincoln students Abby Smith and Harrison Grasso used Nebraska Innovation Studio's (@NIS_Makers) 3D printers to prototype a prosthetic leg for a cat. #Huskers #cats #3Dprinting #Makerspace #LNK #Nebraska pic.twitter.com/54JpLSUp8T

— NIC (@NIC_Innovates) May 14, 2021

Those steps might have seemed incremental to some, but as Smith herself had already learned, they marked real progress when working with such a nimble, independent animal.

“Someone who works with animal prosthetics, that we talked to very early on, had said animals are real creatures with emotions, and they get used to living their way of life,” she said. “So when you’re testing (a prosthetic) the first time, if she even puts it on the floor once or twice, that’s success. I think (it’s about having) not low expectations, but just realistic expectations for how to work with not only animals, but people.

“It is a slow process. Although bodies are adaptable, it all takes time. You have to be patient with the process.”

Observing Olive’s reaction to the prosthetic also helped make real the theoretical. That was especially informative and gratifying, Grasso said, after months of running plans through computer-aided design software, all the while wondering how well the digital might translate to the animal.

Courtesy

Renderings of the prosthetic prototype, which was printed at Nebraska Innovation Studio and weighs less than an ounce.

“As we were doing it, there was an underlying level of uncertainty, just because we have never done anything like this,” he said. “Our design, as far as we knew, was pretty good, but we didn’t know if it actually would work. So by the time we got to the end, and it was relatively functional, I think we were all pretty impressed and pleased.”

Galles felt the same way about both the prototype and the cat. To ensure the team had regular access to Olive while designing and testing its prototypes, Galles moved her from a local animal shelter into her home, fostering Olive throughout the spring semester. And when the project was over, the Galles family, smitten, decided to officially adopt her.

Craig Chandler | University Communication

Beth Galles, assistant professor of practice with the Professional Program in Veterinary Medicine, fostered Olive before deciding to adopt her.

Olive may have gotten a custom prosthetic, a home and a family out of the project, but Smith and Grasso said they gained plenty from the experience, too. For Smith, it became a smooth on-ramp to her new job with ARYSE, a Lincoln-based startup that can scan, say, an ankle before 3D-printing a form-fitting brace designed to guard an athlete against injury.

For Smith, it became a smooth on-ramp to her new job with ARYSE, a Lincoln-based startup that can scan, say, an ankle before 3D-printing a form-fitting brace designed to guard an athlete against injury.

Grasso is currently applying to medical school, hoping to eventually apply his engineering background toward the design of innovative medical devices not unlike the one he just helped fabricate. In the meantime, the project stands out on a résumé and might give him a leg up in the application process.

“This was a really cool combination of all the things that you learn in engineering school,” he said. “And I think our project, especially, approximated a professional setting rather well. It incorporated a lot of the things that maybe you see in an internship, or you could expect to see if you’re working as an engineer in the future.”

Working on behalf of such an adorable client — one that captured the interest of friends and family — was a nice bonus, the engineers said.

“I think the nature of the project itself, and the fact that we worked very closely with a specific cat who was very cute, it just pulls on people’s heartstrings,” Smith said. “People were very invested all along and happy to hear that it did exceed our expectations.

“And Olive ended up being such a sweet cat. We were very lucky to work with her.”

a cat with 3D-printed prostheses lives in Perm

You are here

Home

They put it on their paws. About two years ago, a Permian cat named Odin found a new life - he was given the opportunity to walk again. The crippled animal was then operated on, installing unique prostheses.

One of the nine lives of the cat Odin almost ended two years ago. The red fluffy was found crawling without hind legs in one of the villages near Kungur. How the cat lost its limbs is unknown.

Marina Startseva, owner of the cat Odin:

We suspect the following has happened. Someone mocked the cat, cut off his paws. At one time he rested somewhere, but then he crawled to the village for help, where the inhabitants found the opportunity and desire to turn to Perm for animal protection.

Also, the cat was missing part of the left eye, the wounds festered and rotted. In the regional capital, the cat was given emergency medical care, after which a series of operations were performed: the damaged part of the hind legs was amputated, stumps were formed, and the rest of the eye was removed. The new mistress took the already treated redhead from the shelter. The cat moved around the house with difficulty and at first lived near the bowl and tray.

Marina Startseva, owner of the cat Odin:

- I began to get very worried because he did not move at all, I went to the clinic to our specialists, and the orthopedic surgeon said that there is a miracle clinic in Novosibirsk, with a miracle doctor who developed this technique himself and successfully prosthetics animals.

Without hesitation, the woman took her pet to Novosibirsk, to the veterinary clinic, where the most complex operations are performed on animals. Here, the cat was fitted with artificial limbs, on which he went down in history as the first Permian cyborg cat. Artificial paws are intraosseous titanium implants made by 3D printing.

Sergey Gorshkov, veterinarian:

- First, tomography is done, then I usually draw the prosthesis, and after that we print it on a 3D printer. What is the purpose of these prostheses? The fact that when we can immerse it in bone, the bone grows into titanium. This is what dental implants are based on. If a person has lost a tooth, they will do just such a technology. In animals, it's just very difficult. Because with the teeth is not such a load as on the paws.

Now Odin stands confidently on all four legs. And leads a normal "cat" lifestyle.

Marina Startseva, owner of the cat Odin:

- The cat had a completely passive life lying in the corner, and now he behaves like an ordinary cat.

He jumps on the bed, he jumps off the bed. He walks on the windowsills, he licks his paws, scratches his ear. For him, this is a normal extension of his healthy paw.

By the way, the inquisitive cat Odin received such a name not by chance. He was named after a god from Norse mythology. According to legend, the god Odin always sought to know the truth of the universe and in order to expand his knowledge, he made a deal - he gave his right eye.

Marina Startseva, owner of the cat Odin:

- Each person comes to this earth for something, maybe we came for this. Who will help them? They can only count on the help of people.

Source

Other materials:

- The results of the annual competition "Engineering Reserve of Russia" were summed up in Tyumen

- Researchers created inflatable actuators for robots based on an origami pattern

- 3D printed moon base prototype presented in Switzerland

- Finland was the first in Europe to start printing meat on a 3D printer

- Chopped fiberglass: strength test frames of a rigging ring made on a 3D printer

9016 Attention!

We accept news, articles or press releases

with links and images.

[email protected]

[email protected]

A street cat with frostbitten paws will receive 3D-printed prostheses. How new technologies help animals

In Yekaterinburg, a street cat named Biscotti, who has frostbitten paws, will receive 3D-printed prostheses, reports e1.ru. The animal has already been tried on the first new “paw”.

https://twitter.com/tjournal/status/1409461611367211012

In winter, the cat was found in a snowdrift with severe frostbite, due to which his paws lost sensation. The veterinarians decided to amputate them. The operation on the right has already passed, in the near future the left paws will be taken away from the cat.

- So far only one of the four prostheses is ready. It uses several types of materials: the "toe" and the supporting part are made of an elastic rubber polymer, the outer part is made of plastic. Perhaps, in other prostheses, the "sock" will be made of silicone.

- Other artificial limbs will be made after amputation.

- Prostheses are made by 3DLab, a company that used to deal exclusively with dentistry. This is her first experience in creating artificial limbs for animals.

- The cat lives in the Animal Rehabilitation Center of the Ural State Agrarian University. According to his staff, Biscotti is doing well and "does not come across as a deeply unhappy cat who suffers greatly from lack of limbs." He likes to lie on the windowsill and watch what is happening on the street.

How new technologies make life easier for animals

3D printing technology makes it easy and fast to make prostheses for both humans and animals. At the same time, the latter not only make life easier, but often save from death.

- In 2016, Brazilian engineers made a titanium mandible for Gigi's parrot. The upper part of its beak was damaged, due to which the bird could not feed on its own. The titanium prosthesis allowed him, as before, to crack nuts.

- In 2018, researchers at the University of Ontario 3D printed a titanium prosthetic skull. It was implanted in the dachshund Patches. The dog lost part of its skull during an operation to remove a brain tumor.

- In the same year, Russian engineers 3D printed a prosthetic leg for a falcon named Grom, who was hit by a car. It was designed so that the bird could walk and sit on a branch. Thanks to the prosthesis, Grom's life-threatening body distortion disappeared - for birds, this is fraught with death due to the displacement of internal organs.

- In 2019, specialists from the TechnoSpark center printed the first dog paw prosthesis in Russia that fuses with a bone on a 3D printer. The implant was developed for a mongrel named Chance and transferred to a Novosibirsk clinic, where the operation took place. After 2 months, the dog began to walk confidently, using the artificial paw as his own.

- At the beginning of 2020, it became known that titanium bionic prostheses for the front and hind legs were made for a cat in the same Novosibirsk clinic.

They were also 3D printed. The prostheses were implanted directly into the limbs of a cat named Dymka, who lost her paws and tail in the cold. After the operation, she was able to walk and without difficulty overcame the thresholds encountered on her way. Previously, bionic paws were implanted in the same clinic to another cat named Red.

They were also 3D printed. The prostheses were implanted directly into the limbs of a cat named Dymka, who lost her paws and tail in the cold. After the operation, she was able to walk and without difficulty overcame the thresholds encountered on her way. Previously, bionic paws were implanted in the same clinic to another cat named Red.

Where else is 3D printing technology used?

- Evgeny Lobanov, a medical student from Vladimir, made a prosthesis on a 3D printer for a child who was born without an ear. Especially for this, a unique algorithm was developed that allows printing an implant with an accuracy of 50–100 microns.

- An Orthodox chapel was printed using a similar technology in the Yaroslavl region.

- The American company Relativity Space creates a metal space rocket on a 3D printer. It is cheaper and faster than assembling such devices by hand, the creators of the startup say. The first Terran 1 rocket successfully passed all ground tests.