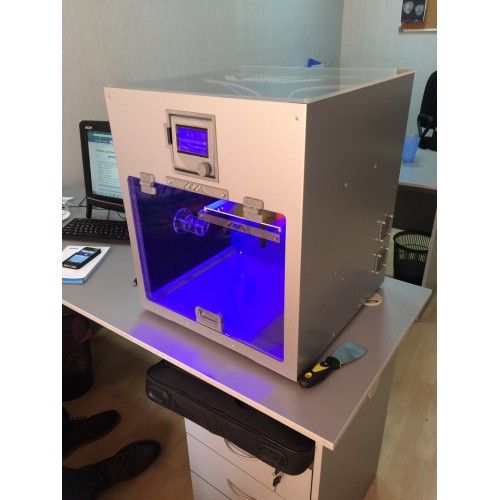

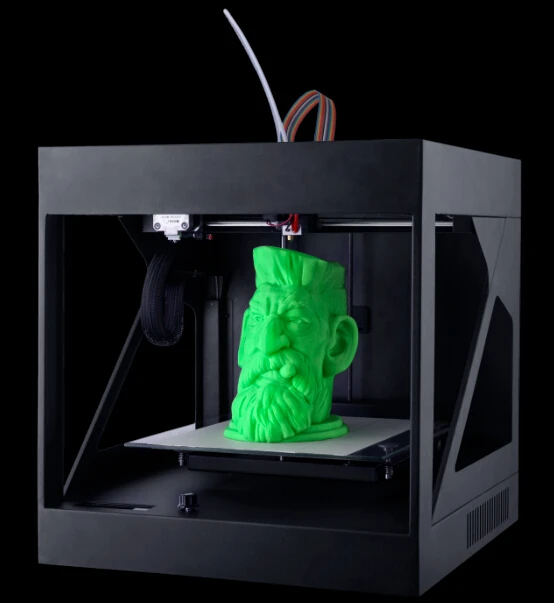

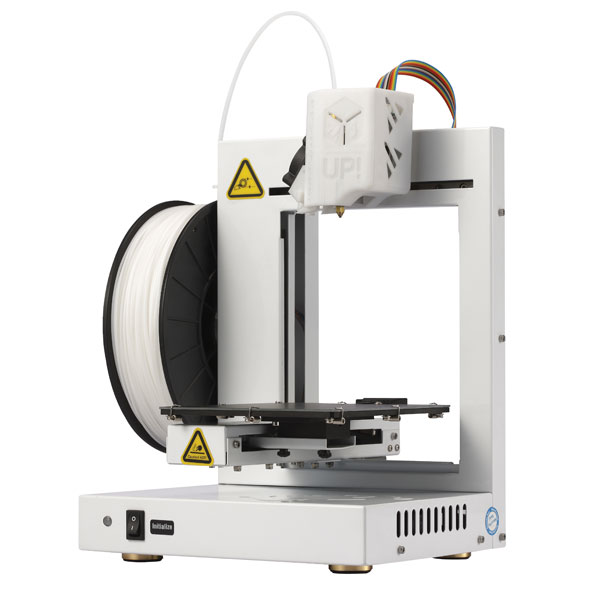

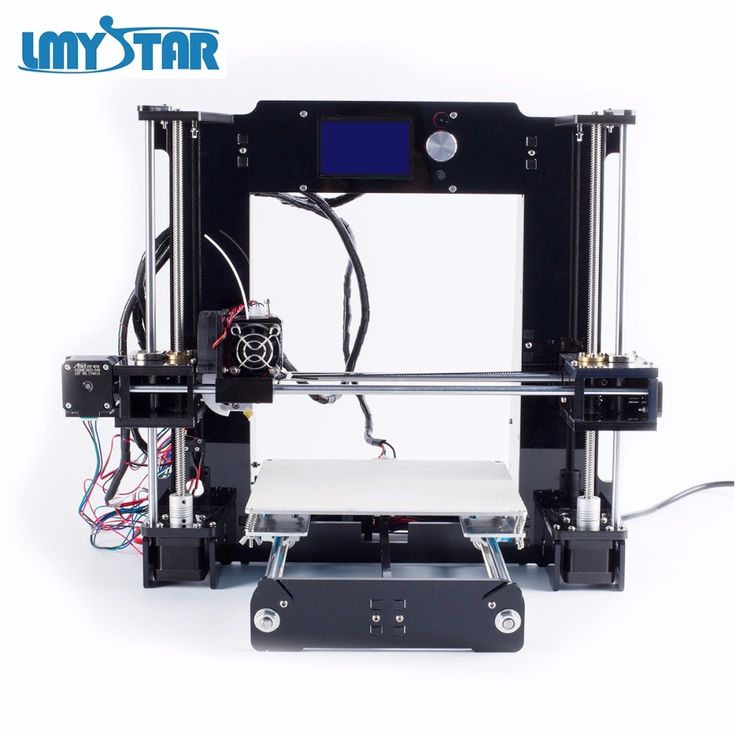

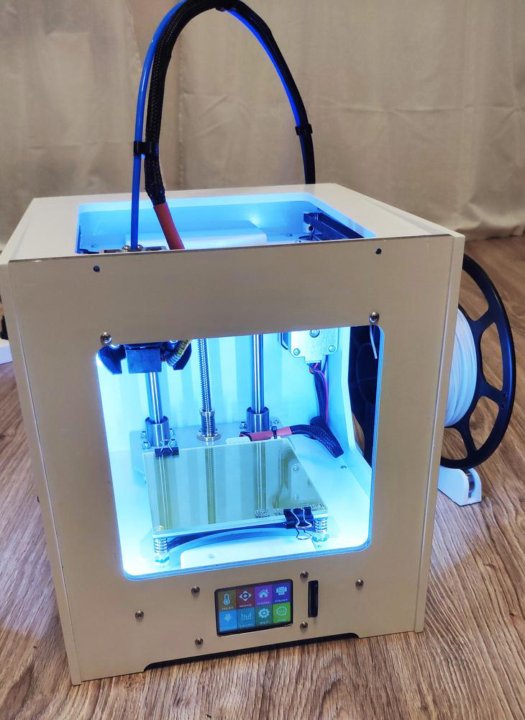

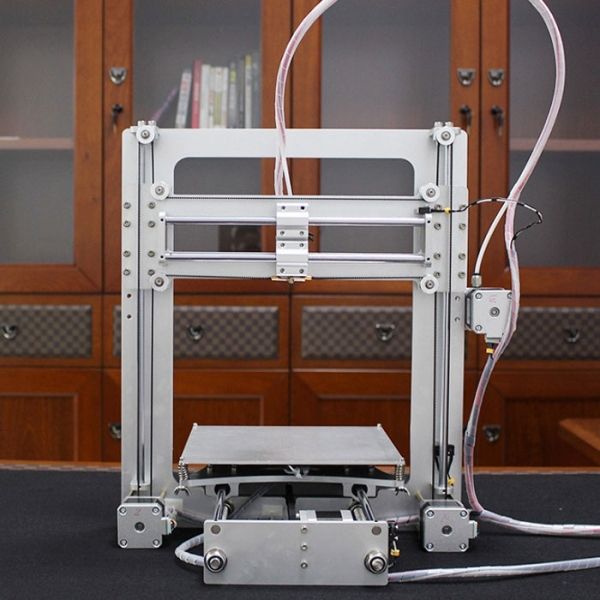

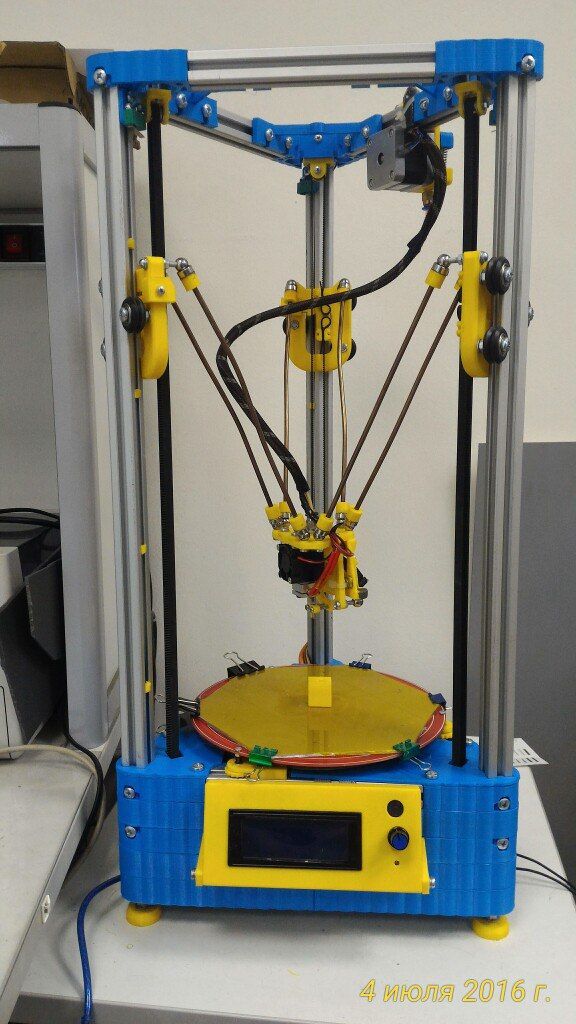

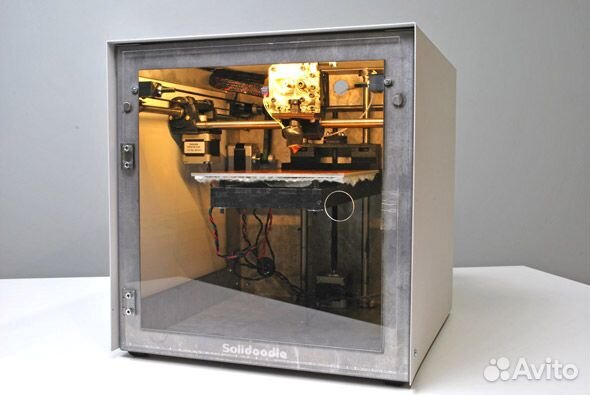

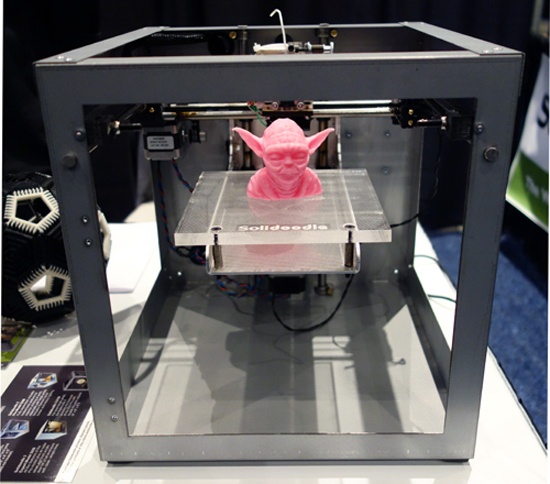

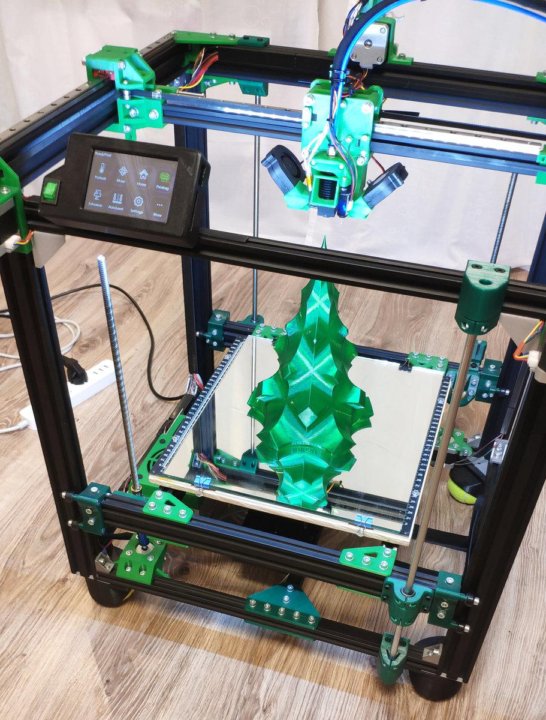

Solidoodle 3d printer 2nd generation

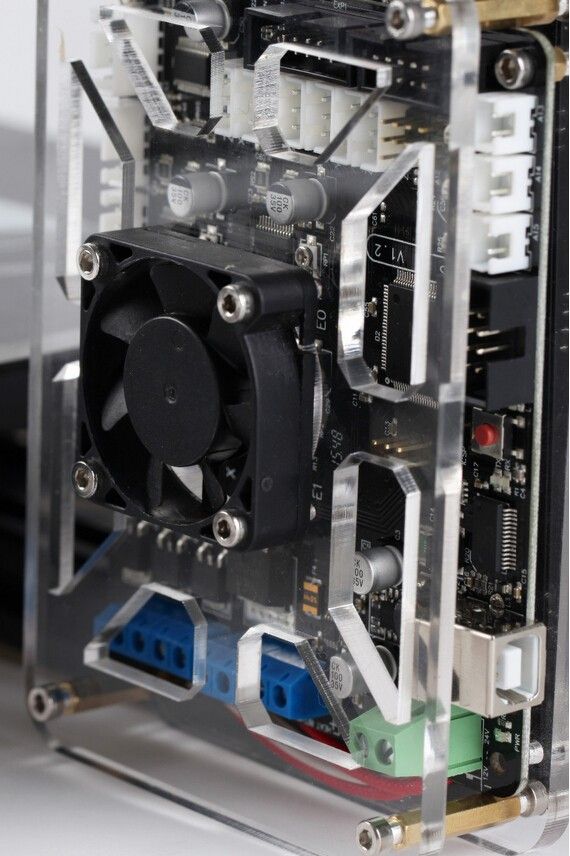

Solidoodle 2 Pro Review | PCMag

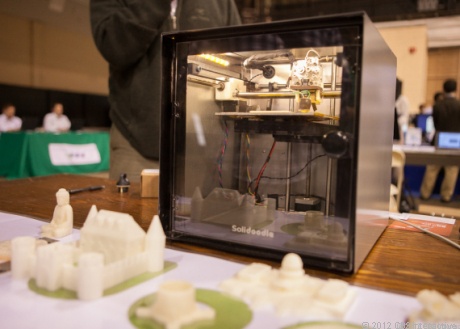

The Solidoodle 2 Pro 3D printer has a consumer-friendly price and does well in consistently printing out plastic objects from CAD files. Solidoodle targets this product toward an eclectic mix of users, from tech-savvy consumers all the way to professionals. Based on the amount of troubleshooting I had to do in getting it up and running, it's suitable for experienced users rather than typical consumers. Anyone setting the Solidoodle 2 Pro, if their experience is at all similar to mine, would need to be very patient and liberally avail themselves of Solidoodle's extensive help resources before being able to print with it. But once my test unit was up and running, the Solidoodle 2 Pro performed like a pro, consistently printing out objects of decent quality with few misprints.

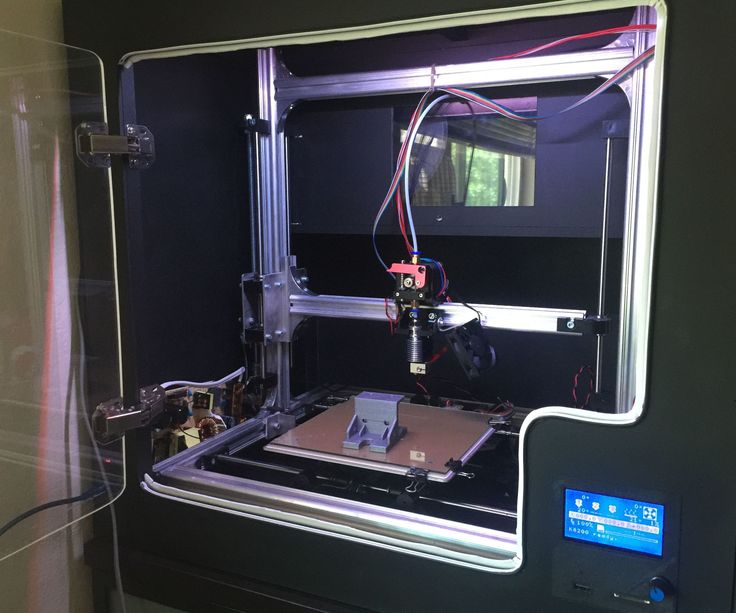

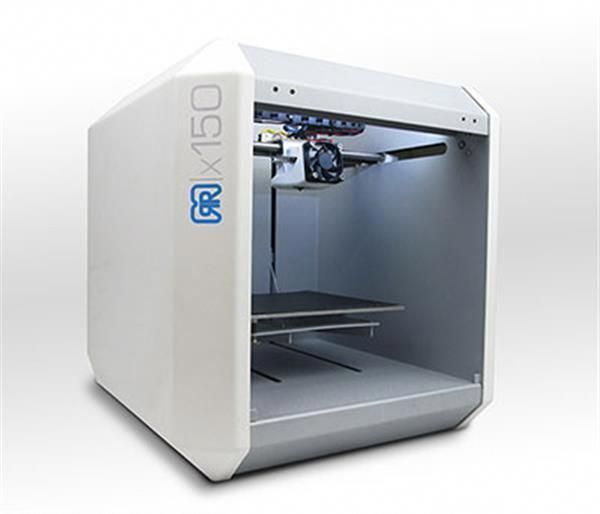

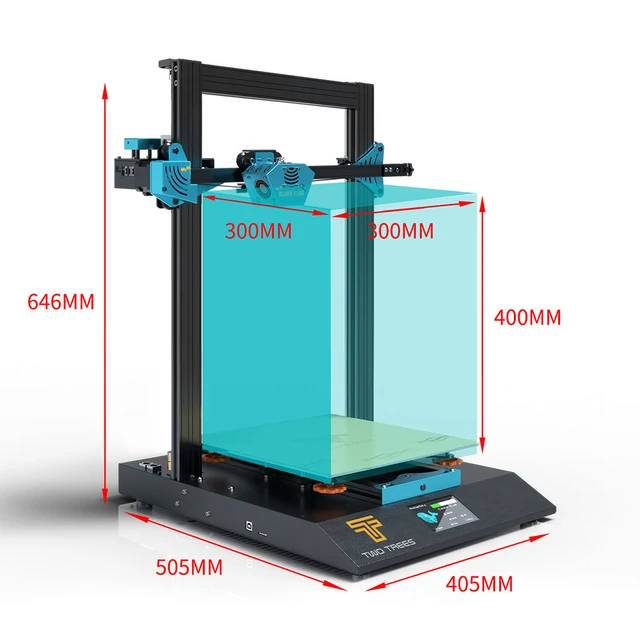

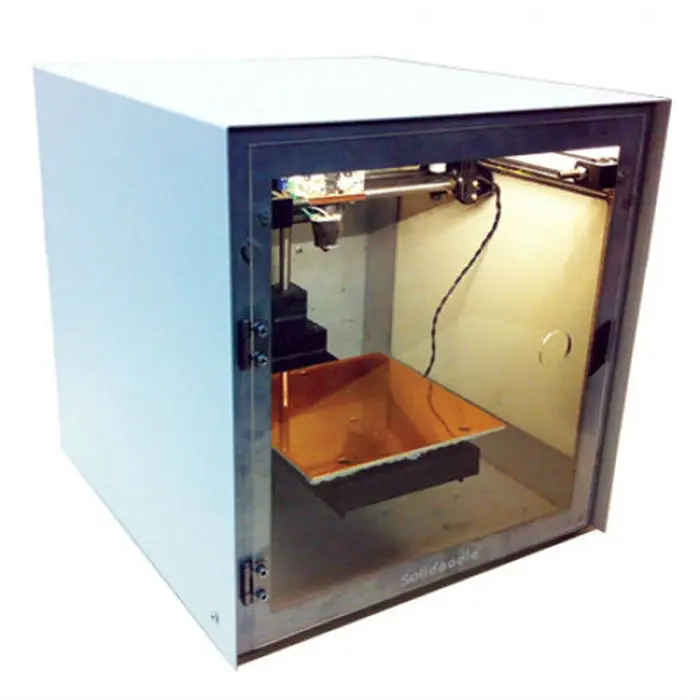

There are several models in the Solidoodle stable. The Solidoodle 2 Pro has a few advantages over the base model in its line (Solidoodle 2, $499 direct): Its build platform is heated, and it has an upgraded spool holder and power supply, plus interior lighting. The Solidoodle 2 Expert ($699) adds a cover and a front door. A third-generation model, the Solidoodle 3 ($799), has a larger (8-by-8-by-8-inch) build platform.

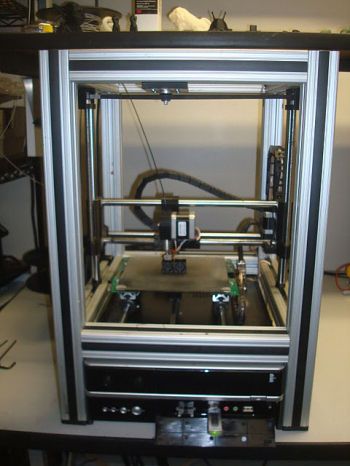

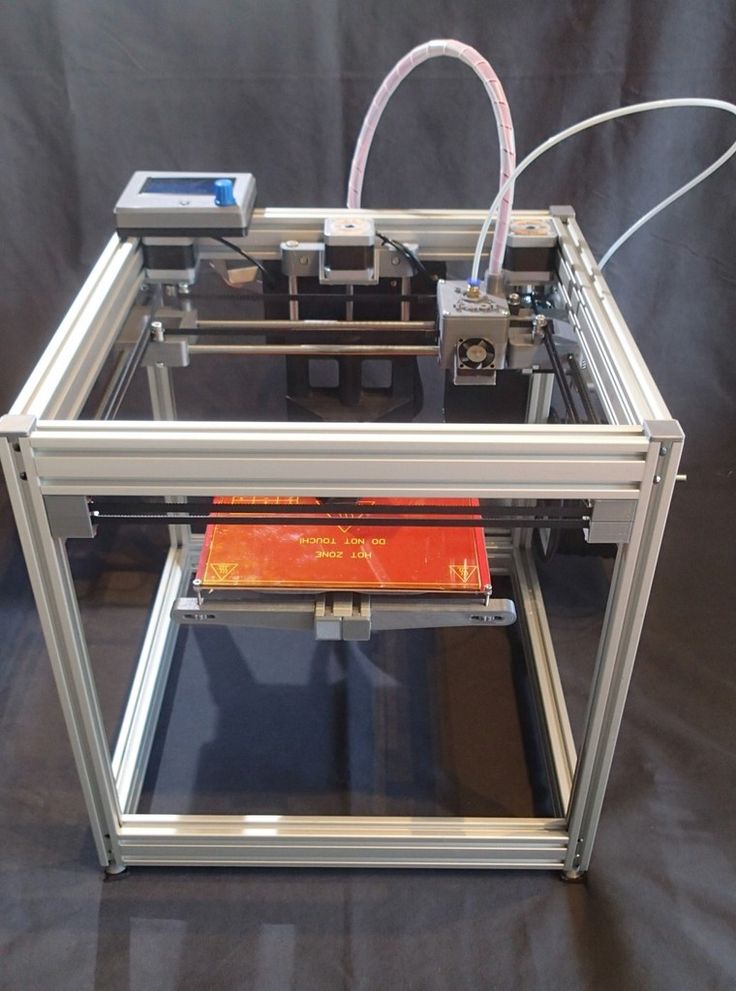

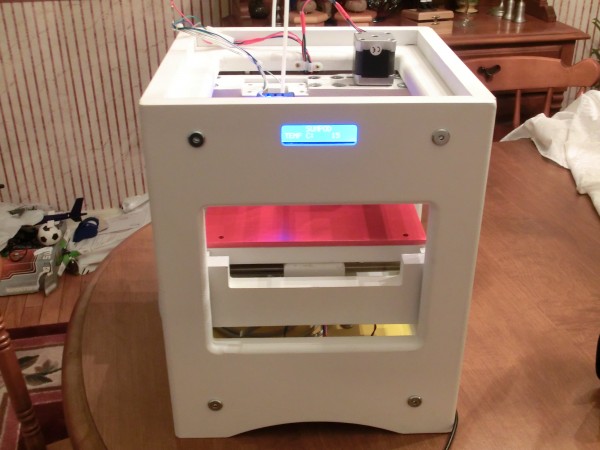

The Solidoodle 2 Pro is nothing if not sturdy. Its open, nearly cubical steel frame, 11.5 by 11.75 by 11.75 inches (HWD), is built to last. The company says the frame can support the weight of a 200-pound man even while printing (no, we did not test this). Its build area is up to 6 by 6 by 6 inches, slightly larger than the 3D Systems Cube 3D Printer ($1,299.00 at Dynamism)(Opens in a new window) , with a build area of 5.5 inches in each dimension.

Continue Reading: Basics and Setup

Basics and Setup

Basics and Setup

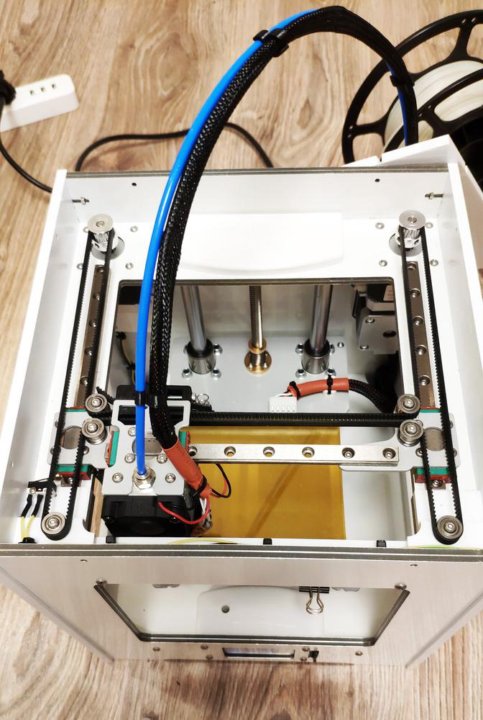

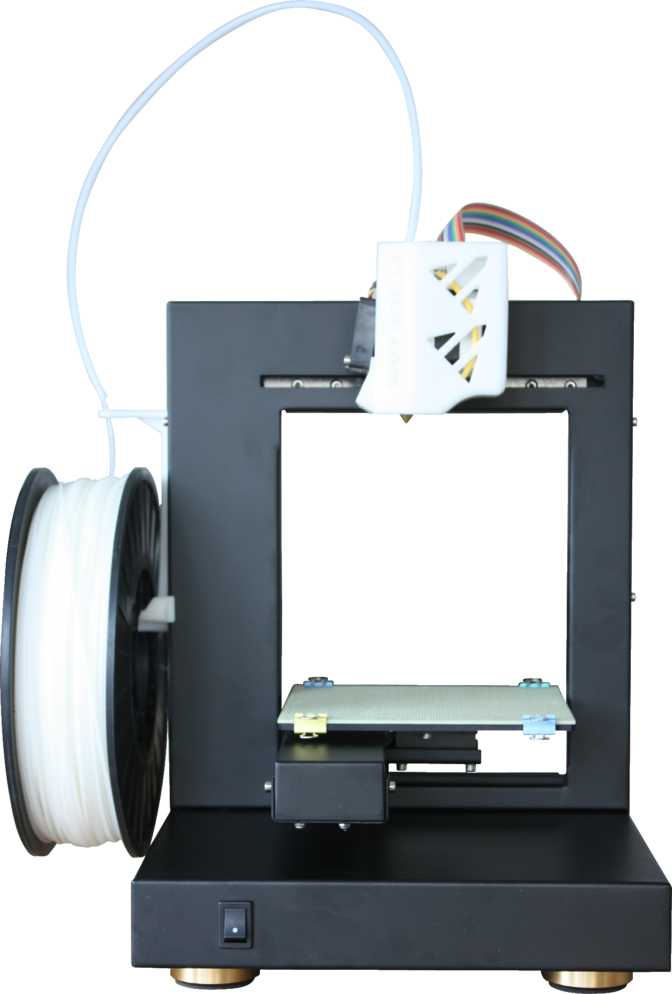

The one physical component that requires assembly is a curved plastic rod to hold the spool of plastic filament that you'll print from. The Solidoodle 2 Pro only comes with a small "starter" supply of filament, but spools of it can be ordered from the Solidoodle site ($43 for a 2-pound spool of ABS plastic). A diagram for assembling the spool holder from its four plastic parts is includedit should take no more than a few minutes to complete. The rod both holds the spool and allows it to turn freely when feeding filament into the Solidoodle 2 Pro.

A diagram for assembling the spool holder from its four plastic parts is includedit should take no more than a few minutes to complete. The rod both holds the spool and allows it to turn freely when feeding filament into the Solidoodle 2 Pro.

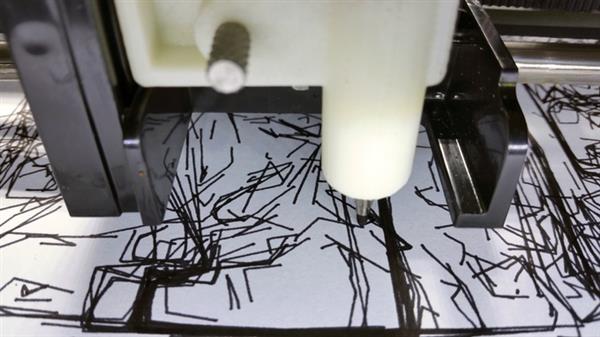

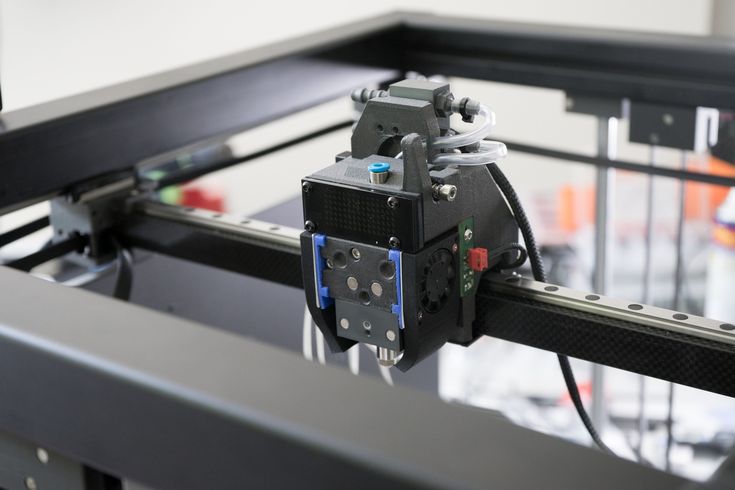

As is typical of 3D printers, filament is fed (from the spool, if you have one) through the back of the printer and down through a hole in the top of the extruder assembly. The extruderthe 3D printing analogue to a conventional printer's print headconsists of a heated chamber and a nozzle that squirts the filament onto the print bed. Once the software is installed and you heat the extruder, you can then push the filament down through the top of the extruder and tap the program's Extrude button, which should grab the filament between a motor and gears and pull it into the extruder, where it will heat up, and a string of molten filament will curl out of the bottom.

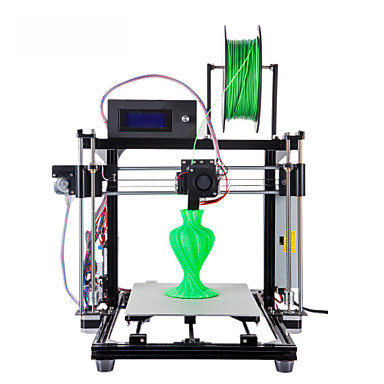

The 2 Pro can print using either with petroleum-based ABS plastic, or PLA, a starch-based, biodegradable plastic. In its store, Solidoodle sells 2-pound spools of ABS plastic at the standard 1.75mm thickness, in each of 5 colors (natural, red, green, black, and blue) for $43 per spool. Solidoodle doesn't currently have a PLA supplier, but you can use spools sold by other 3D printer manufacturers, with the exception of the proprietary cartridges sold by 3D Systems for its Cube 3D Printer, as long as they use the same 1.75mm thickness, which is a widespread standard.

In its store, Solidoodle sells 2-pound spools of ABS plastic at the standard 1.75mm thickness, in each of 5 colors (natural, red, green, black, and blue) for $43 per spool. Solidoodle doesn't currently have a PLA supplier, but you can use spools sold by other 3D printer manufacturers, with the exception of the proprietary cartridges sold by 3D Systems for its Cube 3D Printer, as long as they use the same 1.75mm thickness, which is a widespread standard.

I did all my testing using the ABS plastic that Solidoodle supplied. The company says that the results should be similar using PLA. For ABS plastic, it helps that the 2 Pro uses a heated build platform, as the bottom corners or edges of an ABS plastic job tend to pull up if the room is cool. Such curling was a serious issue with the Cube 3D printer, while with the 2 Pro such curling was absent from most jobs and barely perceptible in those that showed it at all.

Hot ABS plastic sometimes has a burning-plastic smell, particularly at higher temperatures, but with the 2 Pro, with the extruder temperature below 200C it was seldom noticeable and never a problem. ABS plastic fumes are mildly toxic in that particles in the fumes have the potential to irritate one's respiratory tract and can collect in the lungs, and people have reported getting headaches from breathing ABS fumes, so it's best to print in a well-ventilated area, and to print at lower temperatures if the smell is obvious. PLA plastic fumes are non-toxic.

ABS plastic fumes are mildly toxic in that particles in the fumes have the potential to irritate one's respiratory tract and can collect in the lungs, and people have reported getting headaches from breathing ABS fumes, so it's best to print in a well-ventilated area, and to print at lower temperatures if the smell is obvious. PLA plastic fumes are non-toxic.

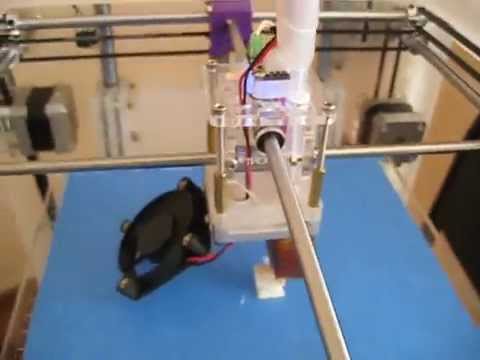

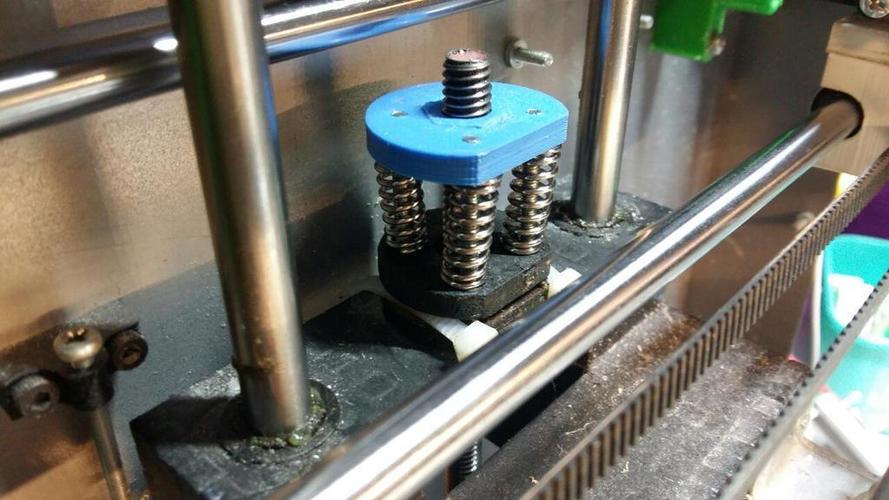

I ran into three significant issues in setting up the 2 Pro. The first was that the filament would not into the extruder. In the second, the extruder nozzle was too close to the print bed and dug into the tape when a print was initiated. In the third, instead of printing a succession of layers vertically, each new layer was offset by a millimeter or so from the previous one, causing the printing to "travel" towards the edge of the build platform.

In each case I called Solidoodle and was directed to an appropriate Help page, with resources that included video where necessary, to solve the problem. In the case of the third problem, for instance, it turned out that the carriage that moved the extruder along the Y axisa 3D printer's motion is along 2 horizontal axes (X and Y), as well as vertically (Z axis)was not moving freely when pressed by hand. The fix involved unseating a motor, loosening several belts, making sure that several rods were properly greased, and then reseating the motor. When I tried printing, the print layers still traveled, so I repeated the fix process, and after that the Solidoodle printed vertically as it should.

The fix involved unseating a motor, loosening several belts, making sure that several rods were properly greased, and then reseating the motor. When I tried printing, the print layers still traveled, so I repeated the fix process, and after that the Solidoodle printed vertically as it should.

Working through all these issues took a lot of time (the better part of 2 workdays) and tinkering. Nothing was fundamentally wrong with our test unit, but it needed a lot of tweaking and calibrating to get it running right. According to Solidoodle, their printers should be ready to go out of the box; the company does a test print before shipping. I don't know how typical the issues I encountered are, but based on my experience, I'd have to say that the Solidoodle 2 Pro is fitting for hobbyists and others prepared to do a bit of tinkering and to get their hands dirty, rather than consumers looking for a product they can have up and running with minimal setup.

Continue Reading: Software and Printing

Software and Printing

Software and Printing

The printer ships without software, but the instruction sheet points you to the Solidoodle site's How To section for software and setup instructions. Solidoodle uses open source 3D printing programs. With the Solidoodle 2 Pro, you have two choices: Repetier Host or Pronterface, both of which come in versions for Windows, Mac, and Linux systems. On my Windows 7 test system, I installed Repetier Host, an all-in-one bundle designed especially for Solidoodle use.

Solidoodle uses open source 3D printing programs. With the Solidoodle 2 Pro, you have two choices: Repetier Host or Pronterface, both of which come in versions for Windows, Mac, and Linux systems. On my Windows 7 test system, I installed Repetier Host, an all-in-one bundle designed especially for Solidoodle use.

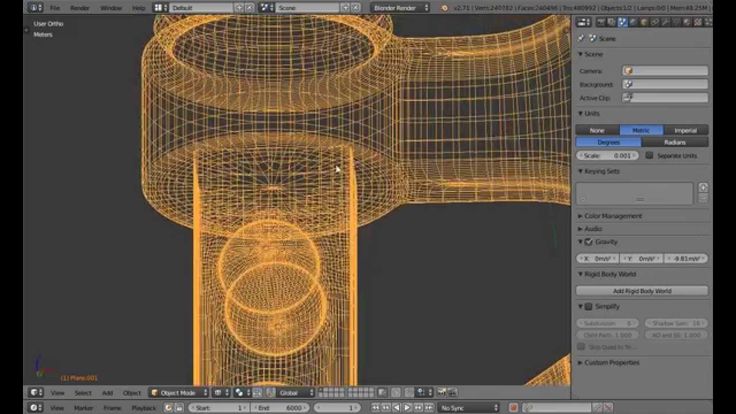

To print from the Solidoodle 2 Pro using buttons from Repetier Host's top bar, you connect to the printer, then select and load a 3D printable STL file. A window on the left side of the screen shows a 3D representation of the printer's build area and whatever object is loaded. At right, an Object Placement tab is open, letting you scale, remove, rotate, or translate the object. The second tab, Slicer, lets you access either the Slic3r or Skeinforge slicing programs. According to Solidoodle, Skeinforge is more versatile, but Slic3r is more user-friendly, so I stuck to Slic3r. Slicing the file, which may take a few minutes to complete, is done by pressing a single button. Some STL files don't slice cleanly, which will show in the 3D visualization under the G-Code tab; Repetier recommends that such files be processed by the netfabb Cloud Service(Opens in a new window).

Some STL files don't slice cleanly, which will show in the 3D visualization under the G-Code tab; Repetier recommends that such files be processed by the netfabb Cloud Service(Opens in a new window).

The third tab, G-Code Editor, lets you see and edit the object's G-Code, the file's instructions for printing the object. Beginners needn't worry about G-Code; more knowledgeable users can make improvements by tweaking the code. The fourth tab, Manual Control, lets you heat the extruder and print bed, as well as control the extruder and motors. When slicing is done and the extruder and print bed have reached the proper temperature, you press a button on the top bar to start the job, and you're off.

The printing process is fairly typical for a RepRap-inspired 3D printer, and notably different than with the Cube 3D Printer. Among other differences, with the Cube you have to apply glue to the removable build platform before each printing, and then soak the build platform in water after printing to remove the printed object and glue. In contrast, the 2 Pro uses a heated build platform and Kapton tape, which you can reuse indefinitely unless the tape gets damaged. Solidoodle sells a sheet of replacement tape for about $10. After printing, the extruder will automatically cool down, but you'll have to turn the print bed's heater off using Repetier.

In contrast, the 2 Pro uses a heated build platform and Kapton tape, which you can reuse indefinitely unless the tape gets damaged. Solidoodle sells a sheet of replacement tape for about $10. After printing, the extruder will automatically cool down, but you'll have to turn the print bed's heater off using Repetier.

Performance

I printed more than half a dozen test objects using the Solidoodle 2 Pro, some of them at both the fine (.1 mm) and coarser (.3 mm) resolution. Comparing the output of one of these (an owl) with a print I did of the same object using the 3D Systems Cube, the Solidoodle's layers were smoother, with fewer extra loops or globs of plastic, even in the lower-res version. The Cube, though, did somewhat better in retaining finer detail than either of the Solidoodle prints. However, this is not an apples-to-apples comparison, as we put the Cube file through the extra "healing" step that its software provides.

The higher-res Solidoodle output was a bit smoother and better overall than the lower-res version, but as it takes some 3 times as long to print the higher-res version (for example, it took about an hour and a half to print one test object at lower res, and nearly 5 hours at high res), the improvement may not be worth the wait, especially if you're printing from a laptop that you'd otherwise move around. Once you initiate a print job, you can see the estimated time remaining to print in Repetier's Manual Control window; the real print times tended to be slightly longer than the first estimates would indicate, but not longer than 10%.

Once you initiate a print job, you can see the estimated time remaining to print in Repetier's Manual Control window; the real print times tended to be slightly longer than the first estimates would indicate, but not longer than 10%.

Continue Reading: A 3D Printer for the Hobbyist

A 3D Printer for the Hobbyist

A 3D Printer for the Hobbyist

As a reviewer, I occasionally come up against the question of whether my experience with a product is typical, or if there's something unusual about my test unit. If there's an obvious defect, the answer is clear, but there's a large gray area. Solidoodle states on its site that its 3D printers should be ready to go out of the box once you install the software and insert the filament. In my experience, it took a lot longer, and required considerable troubleshooting. To its credit, Solidoodle offers the online resources to deal with all the issues I encountered, and once it was set up, the printer has operated relatively trouble-free. I can't say how commonplace the issues I faced are, but only that I had to resolve them, and that at least some users are likely to face them.

I can't say how commonplace the issues I faced are, but only that I had to resolve them, and that at least some users are likely to face them.

To hobbyists and tinkerers, working through setup issues is all part of the process. I did feel a sense of accomplishment as I resolved each one with the help of Solidoodle's resources, and even more so now that the Solidoodle 2 Pro has performed well, with reasonably good output and few misprints, since I got it up and running.

A typical consumer, used to products with reasonably simple and straightforward setups, would likely soon be tearing their hair out if their setup process resembled mine. At least I'd already had the experience of reviewing one 3D printer and assembling a second one from a kit. Though I can't recommend the Solidoodle 2 Pro for average consumers, it's a great low-priced choice for someone who doesn't mind doing a good deal of troubleshooting (and getting their hands dirty) if need be. The end result should be a very sturdy and smoothly running 3D printer.

The 3D Systems Cube 3D Printer was much easier to set upwe ran our first successful test print with it barely half an hour after unboxing the Cubeand its software made quick work of preparing files to print. Unlike with the Solidoodle, a lot of the printer's functions, such as heating the extruder, are performed automatically when you launch a print job. But you have to apply glue to the print bed, and wash the glue off to remove the finished object from the print bed, while the Solidoodle's heated print bed eliminates the need for that. The Cube also costs more than twice as much as the Solidoodle 2 Pro.

Which is the better product? That really depends on your experience, skill level, and patience. Solidoodle was a bit vague about the intended audience for this product, noting that it is priced for consumers but citing, as examples of users, tech-savvy parents introducing their kids to this new technology, high-school science programs, and professionals such as designers and engineers. Based on my own experience, it's not for average consumers looking for a product with quick setup and results. The Cube 3D Printer, despite its operational glitches and higher price tag, is much better suited to that role.

Based on my own experience, it's not for average consumers looking for a product with quick setup and results. The Cube 3D Printer, despite its operational glitches and higher price tag, is much better suited to that role.

For hobbyists, and indeed anyone willing to endure a potentially arduous setup process, the Solidoodle 2 Pro has much to recommend it. It is a good-quality, sturdy 3D printer at a modest price. Should one encounter setup or operational problems, the company's solid support resources will help work through them. This makes it a very appealing choice for the tinkerers of the world, and is better at that role than the Cube, whose self-contained ecosystem doesn't even allow you to use filament from competing brands.

Like What You're Reading?

Sign up for Lab Report to get the latest reviews and top product advice delivered right to your inbox.

This newsletter may contain advertising, deals, or affiliate links. Subscribing to a newsletter indicates your consent to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. You may unsubscribe from the newsletters at any time.

Thanks for signing up!

Your subscription has been confirmed. Keep an eye on your inbox!

Sign up for other newsletters

Compare 3D Printers : Prices, Specs, Technologies

Anisoprint

From 15,000€

Anisoprint is a Russian manufacturer of professional 3D printers that develops FDM/FFF machines. Its 3D printer…

Compare View details

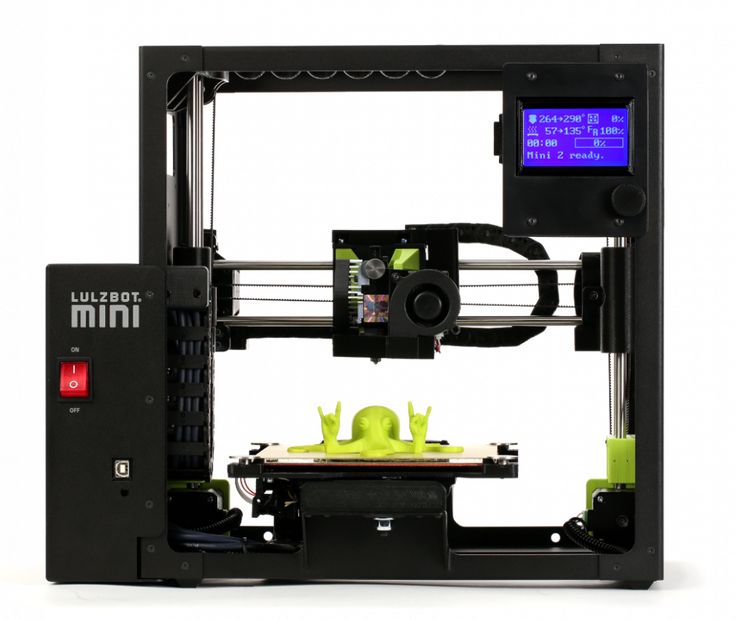

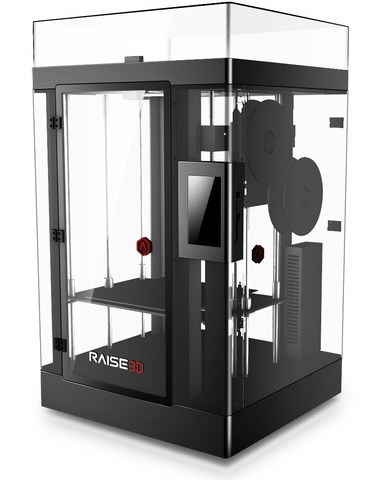

Raise3D

3.7/5 (7 votes)

From 6,249€

The Raise3D Pro3 Plus is a large format printer for professional and industrial use. With twice…

Compare View details

Raise3D

From 3,999€

The E2CF, A High-Strength 3D Printer The Raise3D E2CF is an industrial 3D printer designed by…

Compare View details

Anisoprint

From 27,000€

Anisoprint is a professional 3D printer manufacturer based in Luxembourg that develops FDM/FFF machines. Its 3D printer…

Compare View details

Raise3D

3.3/5 (22 votes)

From 4,749€

The Pro3 is a dual extruder printer with a build volume of 300x300x300 mm. It builds…

Compare View details

Prodways

4.3/5 (0 votes)

Price on demand

A subsidiary of Prodways Group, Prodways Tech is one of Europe’s leading manufacturers of 3D printers.…

Compare View details

3D Systems

2.7/5 (39 votes)

From 500€

The ZEUS is an all-in-one 3D printer, combining 3D scanning, 3D printing, 3D copying and even…

Compare View details

XYZprinting

3.4/5 (10 votes)

From 2,000€

The da Vinci Jr. 1.0 3-in-1 is, as its name suggests, a multifunction 3D printer with…

Compare View details

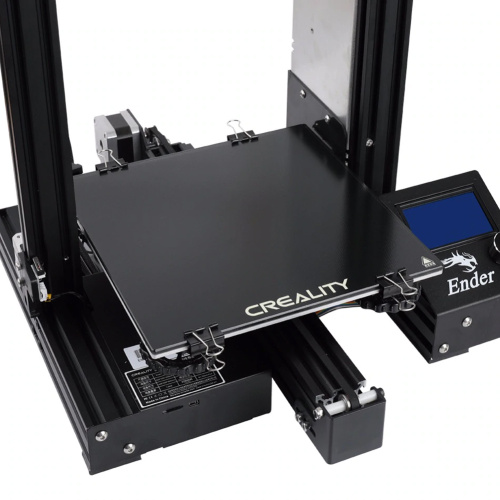

Creality 3D

3. 0/5 (13 votes)

Price on demand

Founded in 2014, Creality needs no introduction. The Chinese company, which develops thermoplastic extrusion 3D printers…

Compare View details

2.9/5 (31 votes)

From 500€

The Mbot Cube is available in two versions with either 1 or 2 print heads. This…

Compare View details

3DGence

3.7/5 (65 votes)

Price on demand

The INDUSTRY F340 from the Polish manufacturer 3DGence is the successor of its first INDUSTRY 3D…

Compare View details

Asiga

2.5/5 (19 votes)

From 5,000€

The first 3D printer to use Pico technology, it is solid and reliable at unbeatable prices.…

Compare View details

Formlabs

2.9/5 (4 votes)

From 2,000€

Considered by many to be one of the main leaders in the additive manufacturing industry, Formlabs…

Compare View details

3D Systems

3. 3/5 (19 votes)

From 100,000€

Crossover ProJet® 6000 printers offer both the ease of use and low operating costs of 3D…

Compare View details

SeeMeCNC

4.1/5 (7 votes)

From 2,000€

The Artemis 300 ARP 3D Printer is a partially assembled delta machine that features a large…

Compare View details

Panther 3D

2.4/5 (8 votes)

From 500€

The 3D Panther from Panther 3D is a Plug & Play printer that can print using…

Compare View details

iBridger

3.8/5 (6 votes)

From 2,000€

The iBridger i340 3D printer is a professional high-temperature machine that will allow you to design…

Compare View details

MakerBot

3.5/5 (96 votes)

From 2,000€

The Replicator 2X is the dual version of the Replicator 2. It has 2 print heads…

Compare View details

XYZprinting

3.7/5 (6 votes)

From 2,000€

The Da Vinci Jr 2.0 Mix is a 3D printer developed by the Asian manufacturer XYZprinting.…

Compare View details

Aconity3D

3.4/5 (11 votes)

Price on demand

Aconity3D GmbH is a German manufacturer of 3D printing machines for metals based in Aachen, Germany,…

Compare View details

Felix Printers

3.4/5 (11 votes)

From 500€

The Felix 3.0 3D Printer from Felix Printers is a RepRap printer available in kit or…

Compare View details

Photocentric

3.9/5 (6 votes)

From 2,000€

Photocentric is a manufacturer based in the United States and England that has developed a range…

Compare View details

3. 2/5 (154 votes)

From 500€

The Cube 3 is the new version of the original Cube, the first generation and the…

Compare View details

3D Systems

From 2,000€

3D Systems, the American manufacturer of 3D printing solutions, was founded in 1986 by Chuck Hull.…

Compare View details

The rise and fall of the idea of home production / Sudo Null IT News

MakerBot has made a bold bet that 3D printers will become as popular as microwave ovens. There is only one problem: everyone else did not share her enthusiasm.

In October 2009, Bre Pettis, with his distinctive sideburns and dark-rimmed rectangular glasses, took his place on the stage at Ignite NYC, threw up his hands and shouted "Hurrah!" twice. Behind him, a screen lit up with a PowerPoint slide showing a photo of a hollow wooden box with wires. Jumping up and down with his rich mop of graying hair, Petis began, "I'm going to talk about MakerBot and the future and the industrial revolution we're starting - which has already started. "

Petis, a former art teacher, became a key figure in a booming market in the late 2000s, a global community of do-it-yourselfers who lived in workshops, workshops, and hackerspaces, as well as at home, working with classic lathes. and modern laser cutters. Petis began his ascent in 2006, recording weekly videos for MAKE magazine, the homemade bible, during which he performed silly tasks like plugging a light bulb into a hamster wheel. In 2008, he co-founded the NYC Resistor hackerspace in Brooklyn. By that time he was already a star. A year later, he launched a startup with friends Adam Mayer and Zach Smith called MakerBot.

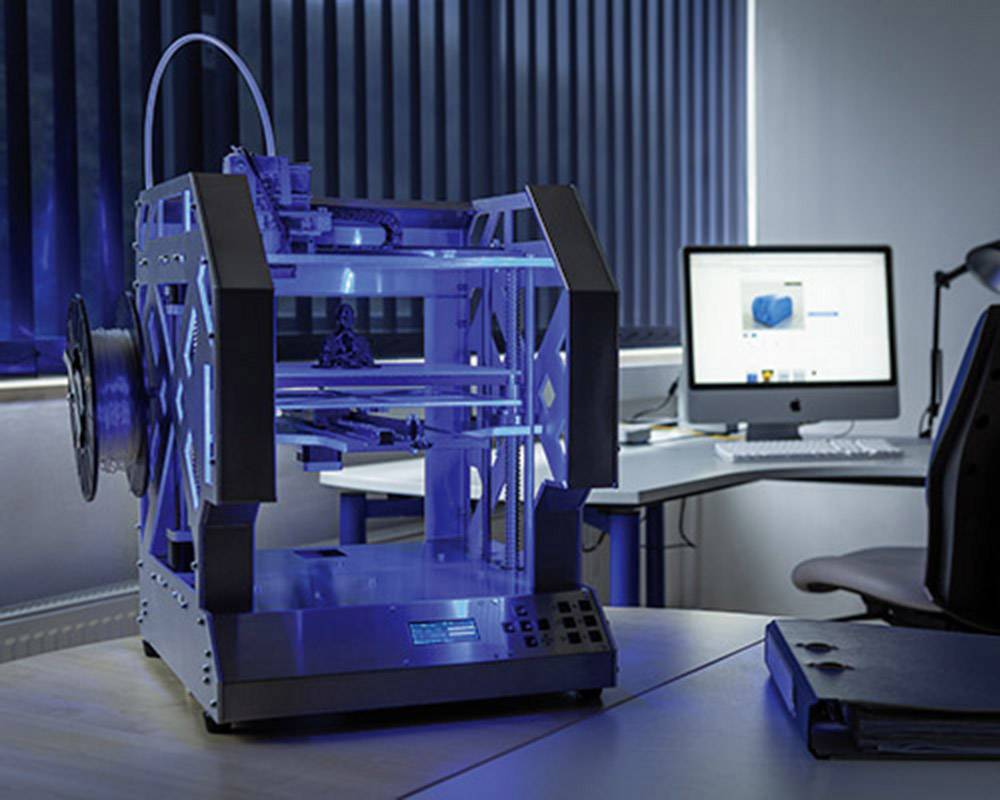

"We had a machine that produced 3D objects and it was awesome," Petis said from the stage at Ignite NYC. Shrinking technology from the size of large $100,000 machines to desktop boxes, MakerBot has started a revolution in 3D printing. With the help of a 3D printer, objects designed on a computer were physically formed, in three dimensions, by superimposing layers of molten plastic on top of each other. And now any MakerBot owner could design and print their own objects.

And now any MakerBot owner could design and print their own objects.

From Pettis's point of view, the consequences of this were startling. People printing objects at home could go to the store less often and do whatever they want. He shared a story about “opened happiness”: a certain person needed a ring to propose, and he opened it. For five and a half minutes, Petis lauded what he said was "Industrial Revolution 2" led by MakerBot.

"You will be your own producer," he said. He concluded his presentation by asking the audience to “make your own future.”

A year before MakerBot was founded, analysts predicted that the global 3D printer market, worth about $1.2 billion, would double by 2015. By the end of 2012, it had practically grown. MakerBot seemed to be just in time: that year the company released its most famous and probably best device, the Replicator 2. MakerBot predicted that the device would appear in thousands of homes. Wires announced in October 2012 that its release was a "Mac Moment" for MakerBot, with the cover featuring a confident Petis holding his new brainchild and the words "This machine will change the world. "

"

“MakerBot is, or at least was like, the Kleenex brand for the 3D printing world. MakerBot has become synonymous with the 3D printer,” said Matt Stultz, who previously worked at the company for five months and is now a digital production editor at MAKE.

Petis has become a cult character. Even before launching the company, according to Staltz, “we were already following everything he did, watching weekly videos and watching his projects.” With the release of MakerBot, he became the king of hackers.

But the second industrial revolution, and the time when each-to-himself-producer, armed with new ideas and a faithful MakerBot, never came. By 2015, Petis, Mayer and Smith were moving on to other projects. A new director and team joined the company, and three waves of layoffs cut the original 600 employees by almost half. This year, the most popular desktop 3D printer is from a Taiwanese manufacturer.

How did MakerBot, the darling of the 3D industry, fall so low and so quickly? Petis did not respond to requests for comment, and Smith and Mayer declined to be interviewed for this article.

We collected information from various industry observers, today's MakerBot executives, and a dozen former employees of the company. Some introduced themselves, while others wished to remain anonymous.

Within a few years, MakerBot needed to make two successful moves. It was necessary to show millions of people the wonders of 3D printing, and then convince them to shell out more than $1,000 for a machine. She also needed to develop technology that was fast enough to keep customers satisfied. And these tasks turned out to be beyond the strength of the young company.

"MakerBot made a big commitment and was trying to meet a market demand that never came," says Ben Rockhold, who worked for MakerBot for four years as an engineer. In pursuit of the dream of everyone becoming a manufacturer, MakerBot tried to produce printers that were both inexpensive and attractive, but they never succeeded.

At a TEDx conference in New York in 2012, Petis said, “When you have a MakerBot, you have a superpower. You can do whatever you need."

You can do whatever you need."

Years passed before someone dared to say that it was not true.

* * *

Early on, the MakerBot-based community flourished around these affordable printers.

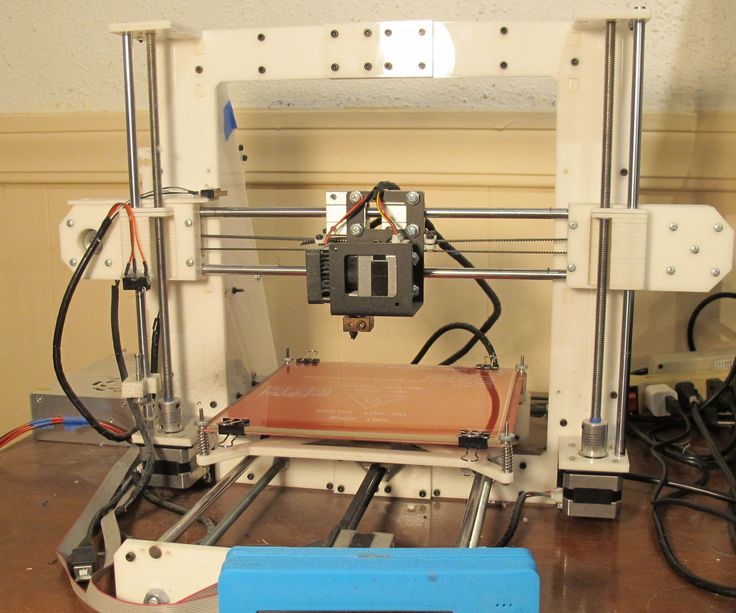

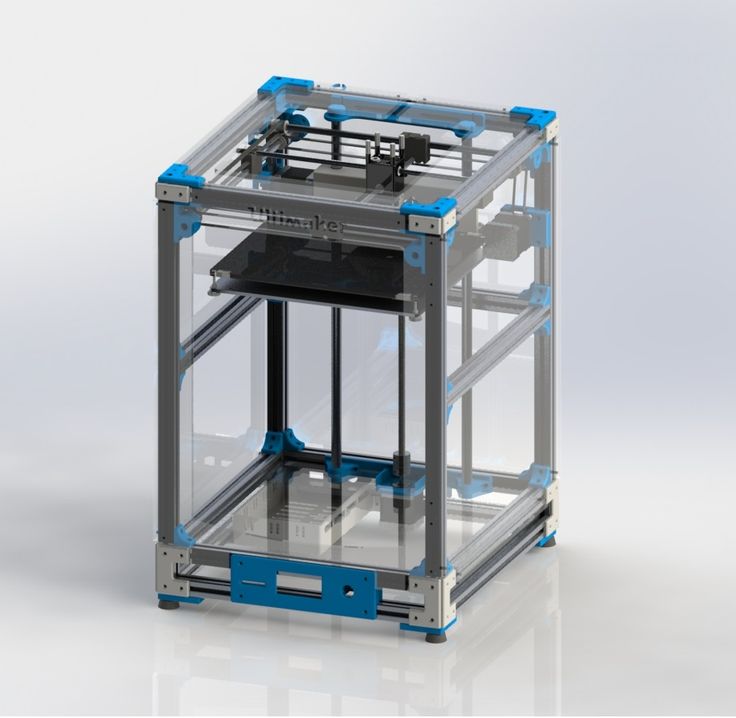

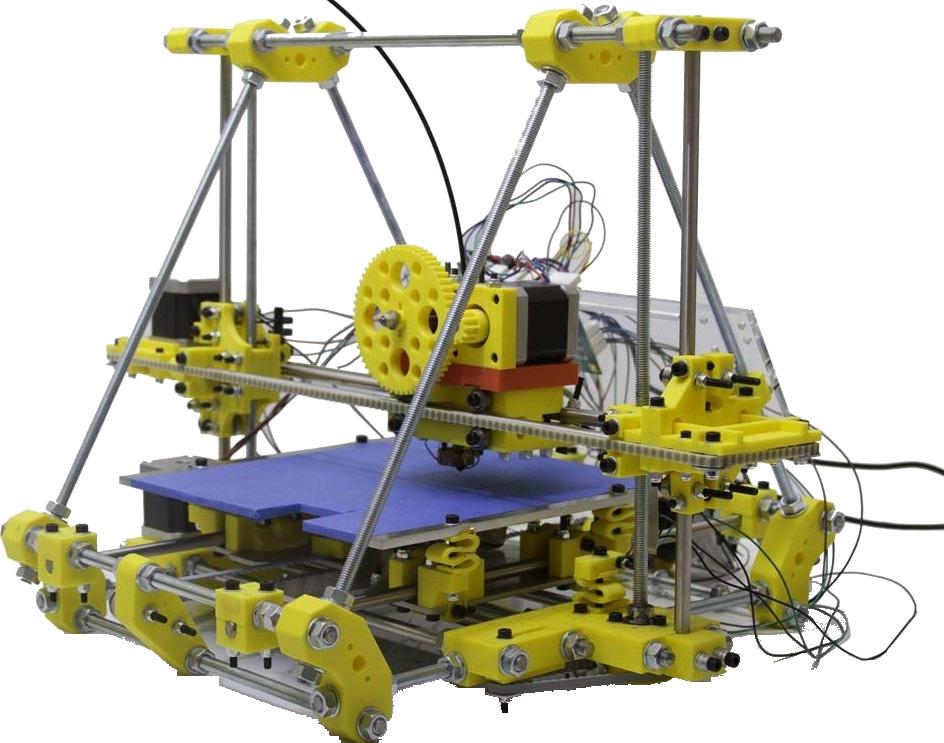

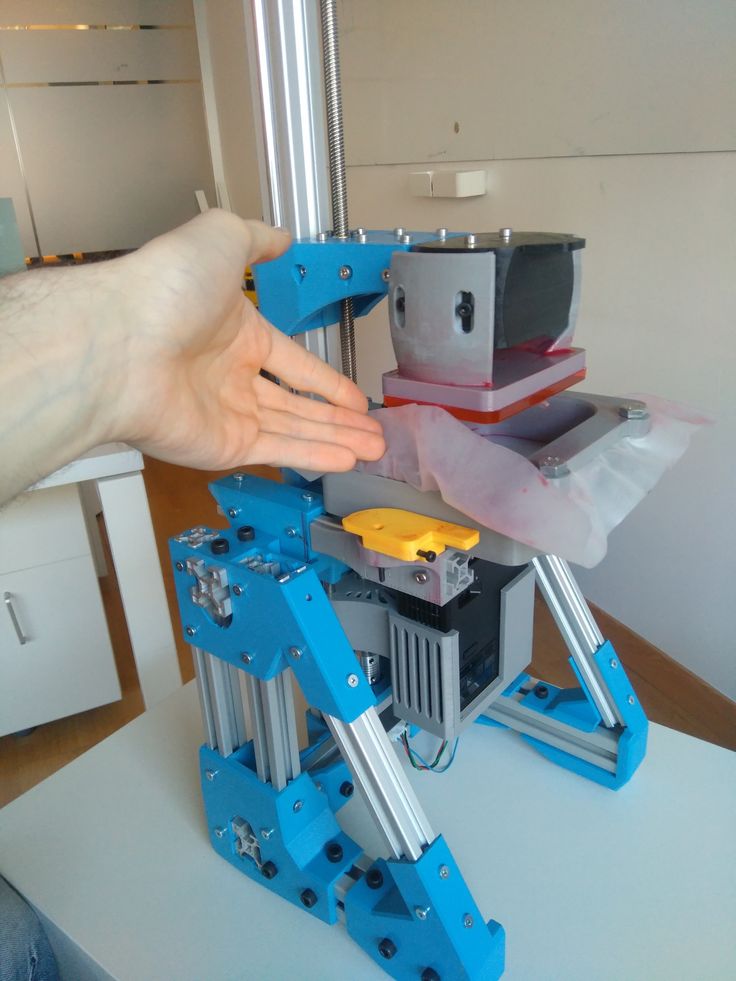

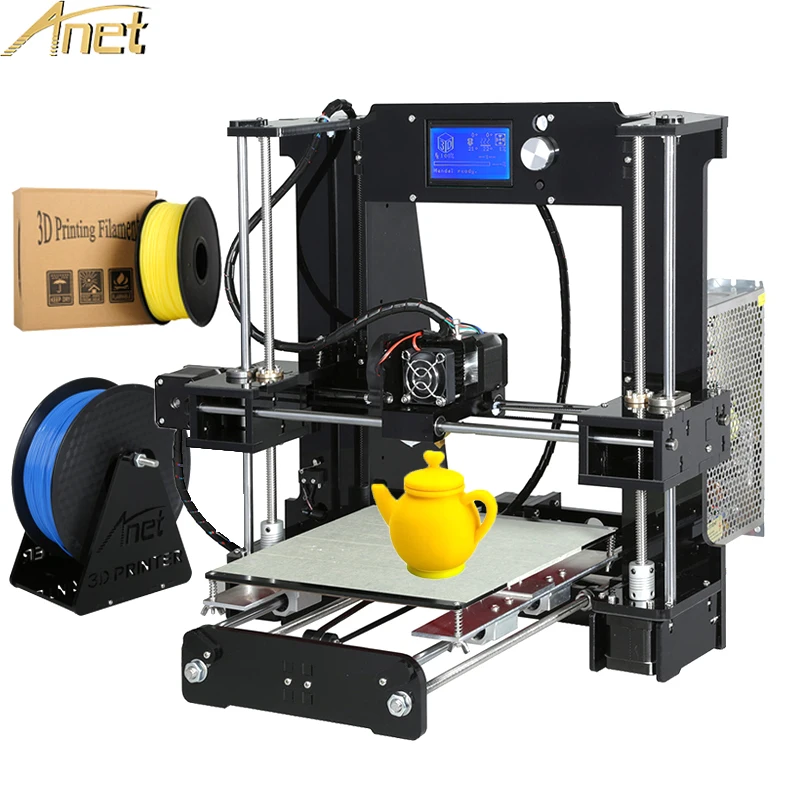

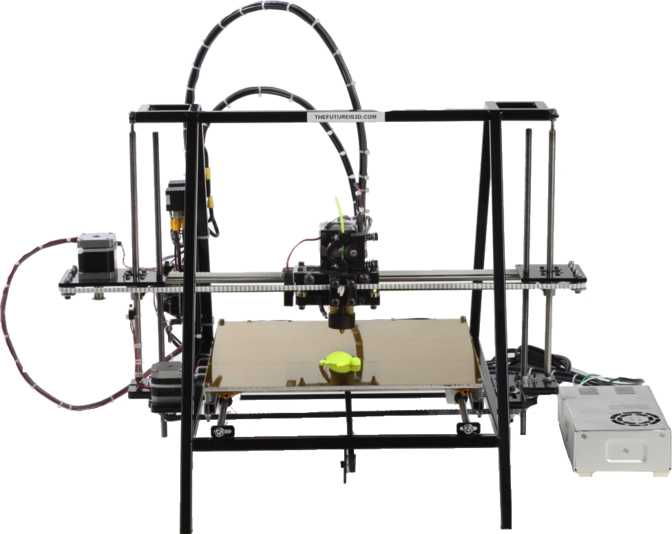

The inspiration came from British professor Adrian Bowyer, who started work on the RepRap, a desktop 3D printer in 2005, that used fused deposition modeling to print objects. Bower wanted to create a printer that could print a copy of itself. One RepRap would spawn another by printing parts, and so on. In New York, three friends, having learned about this, came up with their own idea. Can they make a machine that prints the parts needed to assemble RepRap? And the answer was positive. Working at the NYC Resistor hackerspace, Zach Smith, Adam Mayer, and Bre Petis created the CupCake CNC, a machine that could print RepRap parts on demand.

MakerBot Assembly Parts

“The idea was to make a small number of these printers so that people can make their own RepRap, and the first batch sold very quickly,” says Staltz, who has worked for MakerBot since December 2011 to April 2012.

In January 2009, the trio founded MakerBot with a $75,000 investment, of which $25,000 came from Bower and his wife, Christina. The company was supposed to sell CupCake as a DIY kit. By spring, the company was selling CupCake sets for $750 each. “We went out because of MAKE magazine, we got the attention of the media, who really liked the idea, and they talked about it all the time,” says Rockhold.

CupCake was also an open source project. MakerBot released the hardware and software for the machine for free, and those who bought CupCakes made their own corrections and additions, which the company included in future versions of printers. The open project brought together people from inside and outside the company, and they were all looking for improvements. It also served as a good advertisement, and became the basis and attractive side of MakerBot.

“Openness is the future of manufacturing and we are at the beginning of an era of sharing,” Petis told MAKE magazine in 2011. “In the future, people will look back at businesses that didn’t want to share with their customers and wonder how they could work the other way around.”

“In the future, people will look back at businesses that didn’t want to share with their customers and wonder how they could work the other way around.”

MakerBot represented the revolution in the production of things. A single CupCake could create near-exact replicas of itself (with the exception of bolts and other metal parts), as well as replicas of countless other objects. This movement was to evolve from a geeky subculture into a transformative force that would change society.

The demand for CupCakes was so great that the owners of these machines even helped MakerBot print parts for distribution of new sets. Active forums flourished on Google Groups and Reddit, with fans sharing object designs on Thingiverse, a site started by the company that stored files under a Creative Commons license.

Some amateurs have made corrections to CupCakes themselves. Christopher Jansen, user ScribbleJ on Thingiverse, has figured out how to reduce machine noise and improve print quality. Another user, Whosawhatsis?, has developed a more efficient extruder, a component that extrudes melted plastic.

Another user, Whosawhatsis?, has developed a more efficient extruder, a component that extrudes melted plastic.

"Because our project is open source, users know they have the right to hack the code and design," Petis said in an interview in early 2010. “They also know that if they improve the car, they can share that improvement with others and everyone will benefit from it.”

The corporate culture at MakerBot was also open and flexible. The first office in Brooklyn was more like an experimental laboratory. Employees arrived late and left late. One day you could be packing CupCakes, the next you could be checking extruders. Petis answered support questions, popped into the MakerBot Operators Google Group for comments, and occasionally helped employees navigate the complexities of the hardware by encouraging them to do things that would have gotten them fired in a more strict company. On one of his first days on the job, Ethan Hartman wondered if PLA, the plastic used to create 3D objects, would catch fire if it stuck to an extruder. He remembers that Petis grabbed the burner, a piece of plastic, and they took turns trying to light it on the floor.

He remembers that Petis grabbed the burner, a piece of plastic, and they took turns trying to light it on the floor.

“Nobody worked there to put in hours and make a lot of money selling,” says Hartman, who worked as a customer service and then company manager from April 2010 to August 2012. “People worked there because they I liked the idea that open iron could be part of a commercial enterprise.”

A lot of things were allowed in the company. Interested passers-by were not forbidden to enter unannounced and see what was happening. “In the earliest days, there was no clear operational structure. We didn't think we'd be able to support the project as it started to grow, and there was no expectation that the company would ever grow very much,” says Matt Griffin, public relations manager at MakerBot since December 2009to August 2012.

Employees thought it was a dream job and a chance to turn an alternative future into reality - a world where everyone can become a manufacturer. Hartman says that MakerBot being an open source company was the single biggest reason people loved working on it. They agreed to even lower salaries. One person recalls that his salary at MakerBot was $22,000 less than at his previous job. But working for the company was exciting. They had to turn the market on their own terms.

Hartman says that MakerBot being an open source company was the single biggest reason people loved working on it. They agreed to even lower salaries. One person recalls that his salary at MakerBot was $22,000 less than at his previous job. But working for the company was exciting. They had to turn the market on their own terms.

In September 2010, MakerBot began selling the Thing-O-Matic, their second 3D printer, as a kit for $1,225 (or $2,500 for the assembled version). By that time, many people were already using CupCakes to create various things, such as an owl-shaped headphone winder or 3D puzzles. Thing-O-Matic upped the ante. A Texas school used it to make chess pieces that looked like the landmarks of San Antonio and then sell them for $150. Petis appeared on The Colbert Report and printed a bust of Stephen Colbert on Thing-O-Matic, which is still available for download from Thingiverse. MAKE magazine compared the appearance of Petis with "a five-minute infomercial and commercial" and rejoiced noisily - they say, "who in the audience would not want to buy one for themselves?".

In the following years, trinkets were replaced by more serious undertakings, such as a 3D-printed prosthetic arm. It seemed that the vision of Petis, described by him in 2009, was being realized. People printed the objects they needed. “At first the general theme was that 'We want to change the world'. The democratization of production is a phrase we used both inside and outside the company,” says a former member of the company's web team, who has worked there since September 2010.

The company has kept this spirit alive. MakerBot was the place where everyone went to meetings, and employees had the ending “bot” at the end of their formal position. Andrew Pelkey was hired in the second week of March 2012 to write blog posts, copywrite and oversee social media posts. But he says that he was not a writer, but a “bot” writer (WriterBot).

The Wire's then-CEO Chris Anderson and Bre Petis, 2010, New York

The classic startup mindset is: fail fast, find solutions, iterate, build fast, release. Petis called it "the cult of the job done" and listed the principles on his blog. One of them: “A mistake is considered a done deal. Make a mistake."

Petis called it "the cult of the job done" and listed the principles on his blog. One of them: “A mistake is considered a done deal. Make a mistake."

Petis was proficient in building a community of followers online. Fans adored him, he was an affable, admirable person who loved to create something and explore what 3D printer lovers created. In his talk at Ignite NYC, he showed a photo of a working whistle, designed by a user in Germany and printed out by a New Yorker. “We invented teleportation. Show me how to get a whistle from Germany to New York without a rocket,” he joked gleefully. The audience picked up his laughter.

And over time, it was Petis, not Mayer or Smith, who became the public face of the company. In the 2014 documentary Print the Legend, Petis recalls a conversation with the co-founders when they compared him to another tech prodigy. “You have to be Steve Jobs,” Petis recalls on camera, and then says that he himself wanted to be the equivalent of Steve Wozniak.

But Petis was doing a great job at MakerBot as Jobs, and customers were picking up the Thing-O-Matic and CupCake that MakerBot was selling on Father's Day 2011 for a special price of $455. “The typical MakerBot user was someone who recently found out that 3D printers are cool. And when they found out that they could be bought for $1,000 or less, it completely turned their heads,” says Hartman.

It wasn't just tech journalists who wrote about MakerBot anymore. Rolling Stone wrote about Thing-O-Matic. CBS Evening News wondered if the ubiquity of MakerBots would give us the ability to create anything. The New York Times printed Thing-O-Matic diagrams.

By August 2011, MakerBot had sold 5,200 printers. It received $10 million in investments that month — from the Foundry Group, Bezos Expeditions and others — and began to grow by adding another office in Brooklyn. By autumn, MakerBot employed 70 people.

The excitement grew, but early employees felt that change was inevitable. “Collecting investments is what got people excited. The attitude has changed to 'Now we have to grow dramatically and start growing the company at a tremendous rate',” says Hartman.

In a post about the investment, Petis wrote that the investment and active hiring was necessary to "democratize manufacturing and make 3D printing easier for everyone!".

* * *

The company knew it needed a simpler, plug-and-play printer to attract people other than hackers. “The kits were difficult to assemble. People needed pre-assembled things that just work,” says Hartman.

So MakerBot decided to develop and present at the 2012 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) their new "MMM" product, the Mass Market MakerBot. It was planned that the cost of the MMM would be comparable to the cost of a game set-top box - and no self-assembly. Such a device should have appealed to typical Walmart and office equipment shoppers.

The company secretly orchestrated the development of MMM by opening a subsidiary in China, a "crazy top-secret project" as one former employee called it. Zack Smith, an engineering specialist, became the head of development. He took key engineers from Brooklyn and China.

But in September 2011, Petis decided to change the course of the company. He called the members of the R&D team and announced that in three months they should design, build and test another 3D printer, The Replicator. “The Replicator was born because Bre showed up to a meeting, grabbed all the developers in Brooklyn, and said, we need a printer for CES, but didn't say why,” says Rockhold. Boxes of MMM versions arrived in Brooklyn intermittently, but "the rate of printer improvement was very slow," says Rockhold.

CES was approaching, and Pettis wanted to see the printed objects for verification: one the size of a loaf of bread and the other a DeLorean from Back to the Future. Replicator passed the test and became the main number of the company at CES. Its retail price was $1749.

It never became an inexpensive printer, but it still won the "Best Emerging Tech" award at CES. It had a certain charm - the frame of the printer was made of balsa. And it was sold fully assembled. The hardware and software were still open source, so the community could continue to support the project. And besides, the fans themselves could fix possible problems, which made the Replicator a workhorse in their eyes.

It had a certain charm - the frame of the printer was made of balsa. And it was sold fully assembled. The hardware and software were still open source, so the community could continue to support the project. And besides, the fans themselves could fix possible problems, which made the Replicator a workhorse in their eyes.

A few months later, in April 2012, MakerBot ended all operations in China. Zach Smith retired. “There was no way to mention MakerBot China,” says one former employee.

According to Rockhold, people bought the Replicator in "packs". But he says that the printer had serious problems: the heated platforms burned out because the cables did not maintain the desired voltage, and the machine itself was very sensitive to static. If a user who had built up a static charge inserted an SD card with a file to print, the machine could make a loud sound - the sound of the printer being destroyed, or, at best, the sound of an expensive repair.

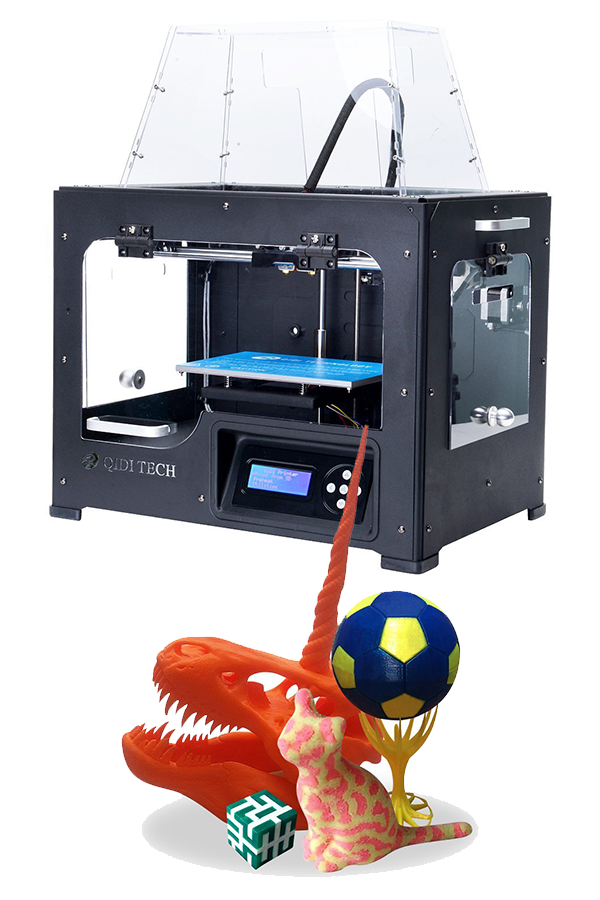

By that time, MakerBot was not the only printer - and was in danger due to the fact that the company could not release printers cheaper. A month before CES 2012, web developer Brook Drumm raised $831,000 on Kickstarter for Printrbot, which was sold as a build kit and cost just $549. The Cube, a glossy plastic desktop printer from 3D Systems, a serious company specializing in industrial 3D printing, also debuted at CES 2012 for $1,299. A few months later, Solidoodle, founded by former MakerBot COO Sam Cervantes, released a new no-build printer priced at just $49.9.

A month before CES 2012, web developer Brook Drumm raised $831,000 on Kickstarter for Printrbot, which was sold as a build kit and cost just $549. The Cube, a glossy plastic desktop printer from 3D Systems, a serious company specializing in industrial 3D printing, also debuted at CES 2012 for $1,299. A few months later, Solidoodle, founded by former MakerBot COO Sam Cervantes, released a new no-build printer priced at just $49.9.

That same year, analytics firm Gartner made an important discovery. On the "Gartner Hype Cycle" chart, which tracks emerging new technologies through stages from over-enthusiasm and disillusionment to sobering realism, 3D printing was placed at the very top of the peak labeled "peak inflated expectations." In an attached report, Gartner clarified that 3D printing refers to home use of printers. The idea of a consumer technology market for "do-it-yourself manufacturers" has reached the height of the hype.

* * *

In May 2012, MakerBot announced its move to the 21st floor of the MetroTech Center in Brooklyn. It already employed 125 people and was preparing to introduce a new printer, the Replicator 2, to the world. “There are no signs of a slowdown in demand anytime soon,” Petis said at the time. "It won't be long until the MakerBot is as common as the microwave!"

It already employed 125 people and was preparing to introduce a new printer, the Replicator 2, to the world. “There are no signs of a slowdown in demand anytime soon,” Petis said at the time. "It won't be long until the MakerBot is as common as the microwave!"

And then TangiBot came out in August.

On Kickstarter, engineer Matt Strong raised $500,000 to mass-produce a replica of the Replicator. "I want to bring a low-cost device to the market that users can trust," Strong said. "Replicator is the best printer and open project."

In other words, Strong simply made his Replicator under a different name. And then he offered to sell TangiBot printers for much less money, thanks to the production in China. So Strong says he could sell the printers for $1,199, $550 less than the Replicator. And technically he could do it - an open source project is not protected by copyright law. Therefore, Strong raised funds on Kickstarter to find a contractor and start production.

The community rallied around MakerBot and declared the TangiBot campaign a robbery. While the campaign failed, the experience made Pettis reconsider his love of open source projects. “The Replicator 2 was ready to go, and Bre saw the TangiBot and said, 'No, we're done with this business strategy,'” says Rockhold.

When the Replicator 2 came out, parts of the machine were covered. The black metal frame was patented, as was the graphical interface that ran the printing software on the computer. These changes looked insignificant, but the public gave the company a scolding. One former employee said that people were furious. All the fixes and improvements they made for the project for years, for free, became closed.

The community was dismayed by this move, and an outpouring of emotion hit the company's operators in the Google Group. Some users showed cautious sympathy: “I want to hear that he, like everyone else, took this decision hard, and I hope he finds a way out. Because if he did that 180 degree turn without any emotion, I would lose respect for Bre and MakerBot. But I doubt that this is the case. I hope it's not, we'll see." Others were more specific: "There is no reason to hope that a closed project will protect the design from theft or reverse engineering and resale. A closed project only harms the community."

Because if he did that 180 degree turn without any emotion, I would lose respect for Bre and MakerBot. But I doubt that this is the case. I hope it's not, we'll see." Others were more specific: "There is no reason to hope that a closed project will protect the design from theft or reverse engineering and resale. A closed project only harms the community."

“I think they were really hurt by us and felt left out,” Pelkey says. "Basically, MakerBot was a club and people felt like they were part of that club."

Employees were confused as well, as shutting down the project alienated the project from the fans, from the community that readily purchased MakerBot printers. “They believed that they had already made a name for themselves, and they no longer needed the community. But 3D printing today is not yet able to live without the community,” says Staltz. "If you piss off the early hobbyists, the 3D printer owners, they won't tell everyone 'Buy a MakerBot'."

The company has turned its back on the original idealism that founded it. The "era of exchange" that Petis referred to a year ago is over.

The "era of exchange" that Petis referred to a year ago is over.

Looking back two years later, Petis seemed to imply that he had always known that MakerBot could not exist in the open. “We could stay open, but that would destroy the business,” he told Politico in August 2014. “So the question is, what is our mission? Do something absurd, utopian, unrealistic? Or are 3D printers for everyone? I chose 3D printers for everyone."

The company has raised the stakes by releasing a proprietary product. So far, it has progressed in tandem with a dedicated community that is not very demanding on technical issues. Now, when their printer could not be repaired on its own, and when it had to fit any user, perfect work was required from it.

* * *

In June 2013, MakerBot was bought by Stratasys, one of the world's largest 3D printing companies, for $403 million, plus $201 in performance-based bonuses. MakerBot launched a massive hiring campaign and showed off three new desktop printers for CES 2014. They had new features like WiFi support, LCD displays and a new Smart Extruder.

They had new features like WiFi support, LCD displays and a new Smart Extruder.

But the cost was still too high. The Mini was priced at $1,375. XYZprinting debuted the machine at the show for $499, which is exactly what the Mini was supposed to cost according to MakerBot's 2012 plans that Backchannel got its hands on.

“Bré really wanted to reach this value, but no one was able to do it,” says Jeff Osborne, vice president of sales and business development from March 2012 to early 2013. “He knew that the market needed a cheaper device” .

According to one former employee, some of the machines shown at CES 2014 didn't even work. But still they all received awards. “It was the peak moment of the hype, as even at CES they were ready to give out awards for cars that couldn't even show their work,” he says.

MakerBot did well in 2014. Stratasys' annual report shows that MakerBot sold 39,356 printers in 2014, down just 1,194 printers since 2009.to 2013. Each printer came with a note autographed by Petis stating that this machine would “give you the superpower to do what you can imagine.” By the fall, Staples and Home Depot stores were already selling new printers from MakerBot.

Each printer came with a note autographed by Petis stating that this machine would “give you the superpower to do what you can imagine.” By the fall, Staples and Home Depot stores were already selling new printers from MakerBot.

They again had technical problems - but now the buyers could not help with their solution. More savvy users posted questions in the MakerBot Operators Google Group. One of the most hostile users stated that "after a war that lasted a year, I lost my patience." A petition has surfaced on Change.org demanding that MakerBot recall its printers.

One of the sources of user frustration was the Smart Extruder, which was supposed to inform the user that the plastic had run out. Ultimately, both MakerBot and Stratasys were sued, alleging that the company deliberately released a non-working extruder. In July 2016, the case was closed due to lack of evidence.

On Brokelyn.com, a former employee of the company, Isaac Anderson, blamed the failures of all three machines on the company's decision to move away from the open source project. It couldn't rely on its customer base of "skilled and enthusiastic people who provided a wealth of technology feedback and suggestions for improvement." The new class of buyers, he wrote, "consisted of unskillful people, did not give useful feedback, but gave only unrealistic expectations."

It couldn't rely on its customer base of "skilled and enthusiastic people who provided a wealth of technology feedback and suggestions for improvement." The new class of buyers, he wrote, "consisted of unskillful people, did not give useful feedback, but gave only unrealistic expectations."

Bill Buell was MakerBot's Director of Engineering, which released the three machines shown at CES 2014. He says developing three machines at the same time with a tight deadline was very stressful for the engineering teams. But he also claims that each printer has been extensively tested and met the company's specifications for a ready-to-sell product.

“I can see why Bre wanted to make all three cars. He wanted an explosive response to CES, which is already a habit,” says Buell. "From an engineer's point of view, it was a big risk."

The weaknesses of the printers began to affect the company. In the first quarter of 2015, Stratasys directors spoke of a slowdown in the 3D printer market, and mentioned that MakerBot sales were less than expected. In April 2015, Jonathan Yaglom, director of Stratasys, became the CEO of MakerBot, but the fate of some employees was already sealed. That month, the company said goodbye to a fifth of its employees.

In April 2015, Jonathan Yaglom, director of Stratasys, became the CEO of MakerBot, but the fate of some employees was already sealed. That month, the company said goodbye to a fifth of its employees.

In October of that year, MakerBot laid off another fifth of its employees. “We are not achieving results, which means financial problems,” Jaglom told me at the time. The company reportedly sold just 18,673 printers in 2015, less than half of what it sold in 2014.

Last April, Yagolm announced that MakerBot would close its 16,000 m2 manufacturing facility at 2 in Brooklyn, lay off more employees, and transfer all production to China as the company celebrated the sale of its 100,000th printer. An analysis of the company's reports showed that in the first three months of 2016, MakerBot sold only 1,421 printers.

“In 2014, the company was confident that the consumer market was ripe. In 2015, we realized that the market was not what we imagined it to be,” Jaglom told me the day MakerBot announced it was closing the factory.

Turns out 3D printers aren't all that revolutionary, at least not yet. Big companies like General Electric and Ford are experimenting with 3D printing and using it to make parts. GE bought the two respective companies this year for $1.4 billion. But the technology is not yet reliable enough, fast enough, and cheap enough to replace traditional technology.

This is also a rather complicated process. To print the desired object, you need to know how to create a 3D design, which, of course, has become much easier to do thanks to online programs such as TinkerCAD. But the extruder head may become clogged during printing. The backing may warp. The result may be crooked, which will require you to rotate the part next time. “It takes a lot of work. It's not like you can push a button and get what you imagined,” says Rockhold.

In the dizzying days of 3D printing, there were no questions to ignore or tasks to put off until later. What is happening now Yaglom calls the "calming down of the hype" in the industry, when the perception of her society finally begins to coincide with reality. Stratasys' stock price stumbled from a record $136 in January 2014 to $25 in October 2015 when MakerBot announced a second wave of layoffs.

Stratasys' stock price stumbled from a record $136 in January 2014 to $25 in October 2015 when MakerBot announced a second wave of layoffs.

“People want things to happen faster, we live in a world of speed, but it takes time to get a new thing to market,” says Jenny Lawton, who joined MakerBot in 2011 and has worked as an acting director. CEO from late 2014 to early 2015. “3D printing is still in progress. She looks like an awkward teenager."

Other 3D printing companies also suffered. Solidoodle suspended work last spring. Electroloom, which created fabric printing, closed in August, in part due to a "poorly defined market opportunity." Stratasys' main competitor, 3D Systems, announced in the fall of 2015 that it was closing a factory in Massachusetts that employed 80 to 120 people. At the end of that year, the company decided to stop selling Cube printers. Like MakerBot, it struggled to compete with smaller startups that had lower overheads and cheaper printers. Today, Taiwanese XYZprinting knocked MakerBot out of first place to become the world market leader in desktop 3D printers.

This year's Wohlers Report, an annual report on the 3D printer market, seems to be saying the opposite: 270,000 desktop printers were sold last year. But mostly these cars are bought by commercial organizations and schools, not individuals.

"The plan followed by MakerBot, 3D systems and others is an illusion - one in which the average home user has one or more of these machines - there is simply no market for them," says Terry Wohlers, president of the consulting firm that publishes the report. . "Maybe that's where MakerBot got it wrong in the first place, believing there was such a market."

* * *

On a sunny September morning, Jonathan Yaglom welcomed journalists, business leaders in Brooklyn, and MakerBot employees to the MetroTech Center. The company had good news. It released the sixth generation of desktop printers, the Replicator+ and Mini Replicator+.

During the hour-long presentation, employees talked about larger frames for printing larger objects, software and hardware improvements. The new app from MakerBot allows even a novice to walk through the printing process from start to finish. The new printers are much quieter than the previous ones. They can finally work on the desk without distracting people. "We've completely redesigned them entirely," Mark Palmer, Head of User Experience Development at MakerBot, told the crowd.

The new app from MakerBot allows even a novice to walk through the printing process from start to finish. The new printers are much quieter than the previous ones. They can finally work on the desk without distracting people. "We've completely redesigned them entirely," Mark Palmer, Head of User Experience Development at MakerBot, told the crowd.

Jaglom described the change in company policy. In the past, MakerBot "created products and hoped to find consumers." Now the company has changed: it asked users what they needed and developed products for their needs. This was done with an eye to the two markets Yaglom believes MakerBot would be best suited for: professional engineers with designers, and teachers. Today, more than 5,000 schools in the US have MakerBot printers.

Petis stepped down as head of MakerBot in September 2014, and was going to lead an "innovation workshop" at Stratasys called Bold Machines. The goal of the project is to prove that 3D printing can be applied to serious projects, and not just to the production of knick-knacks. In June 2015, Bold Machines spun off into a separate company. Today, Petis runs Bre & Co., a startup that makes “family jewel-level gifts,” the first of which was a $5,800 watch. Petis avoids publicity. But many former employees express admiration for his assertiveness, determination and visionary. “Without Bre, the company would not have been a milestone in the history of 3D printing,” one of them said.

In June 2015, Bold Machines spun off into a separate company. Today, Petis runs Bre & Co., a startup that makes “family jewel-level gifts,” the first of which was a $5,800 watch. Petis avoids publicity. But many former employees express admiration for his assertiveness, determination and visionary. “Without Bre, the company would not have been a milestone in the history of 3D printing,” one of them said.

In retrospect, it's easy to criticize MakerBot for misjudging a potential market. Even icons of innovation are not always capable of inventing the future. "MakerBot, it was the first time people knew there was 3D printing," says Hartman, one of the earliest employees. “It seems to me that this is the essence of success, and at the same time what led to the defeat. She promised a future that is yet to come."

In October, Popis appeared at Syracuse University (USA). At Hendrix Chapel, the university's public gathering space, Petys, still sporting sideburns and dark-rimmed rectangular glasses, told the audience that successful people are those who "show what they can do and do cool stuff. " He was quoting from his polished book of rules of life. These people are members of their own club, he said, and the only requirement to join is to "try to do something amazing."

" He was quoting from his polished book of rules of life. These people are members of their own club, he said, and the only requirement to join is to "try to do something amazing."

"If you do something absolutely stupid, absurd, weird, you will almost always find some kind of innovation that matches it in the normal world," he said from the stage.

The first slide that appeared behind him was a frame with the caption "First Steps with the Future."

Home production: myths and reality

MakerBot has made a bold bet that 3D printers will become as popular as microwave ovens. There is only one problem: everyone else did not share her enthusiasm. October 2009Bre Pettis, with his inimitable sideburns and dark-rimmed rectangular glasses, took his place on the stage at Ignite NYC, threw up his hands and shouted “Hurrah!” twice. Behind him, a screen lit up with a PowerPoint slide showing a photo of a hollow wooden box with wires.

Take advantage of our services

Bouncing around with his rich mop of graying hair bouncing up and down, Petis began, "I'll be talking about MakerBot, and the future, and the industrial revolution we're starting - which has already started. "

"

Petis, a former art teacher, became a key player in a booming market in the late 2000s, a worldwide community of do-it-yourselfers who lived in workshops, workshops, and hackerspaces, as well as at home, and who worked with classic lathes and modern laser cutters. Petis began his ascent in 2006, recording weekly videos for MAKE magazine, the homemade bible, during which he performed silly tasks like plugging a light bulb into a hamster wheel. In 2008, he co-founded the NYC Resistor hackerspace in Brooklyn. By that time he was already a star. A year later, he launched a startup with friends Adam Mayer and Zach Smith called MakerBot.

"We had a machine that produced 3D objects and it was awesome," Petis said from the stage at Ignite NYC. Shrinking technology from the size of large $100,000 machines to desktop boxes, MakerBot has started a revolution in 3D printing. With the help of a 3D printer, objects designed on a computer were physically formed, in three dimensions, by superimposing layers of molten plastic on top of each other. And now any MakerBot owner could design and print their own objects.

And now any MakerBot owner could design and print their own objects.

From Pettis's point of view, the consequences of this were startling. People printing objects at home could go to the store less often and do whatever they want. He shared a story about “opened happiness”: a certain person needed a ring to propose, and he opened it. For five and a half minutes, Petis lauded what he said was "Industrial Revolution 2" led by MakerBot.

"You will be your own producer," he said. He concluded his presentation by asking the audience to “make your own future.”

A year before MakerBot was founded, analysts predicted that the global 3D printer market, worth about $1.2 billion, would double by 2015. By the end of 2012, it had practically grown. MakerBot seemed to be just in time: that year the company released its most famous and probably best device, the Replicator 2. MakerBot predicted that the device would appear in thousands of homes. Wires announced in October 2012 that its release was a "Mac Moment" for MakerBot, with the cover featuring a confident Petis holding his new brainchild and the words "This machine will change the world. "

"

“MakerBot is, or at least was like, the Kleenex brand for the 3D printing world. MakerBot has become synonymous with the 3D printer,” said Matt Stultz, who previously worked at the company for five months and is now a digital production editor at MAKE.

Petis has become a cult character. Even before launching the company, according to Staltz, “we were already following everything he did, watching weekly videos and watching his projects.” With the release of MakerBot, he became the king of hackers.

But the second industrial revolution, and the time when each-to-himself-producer, armed with new ideas and a faithful MakerBot, never came. By 2015, Petis, Mayer and Smith were moving on to other projects. A new director and team joined the company, and three waves of layoffs cut the original 600 employees by almost half. This year, the most popular desktop 3D printer is from a Taiwanese manufacturer.

How did MakerBot, the darling of the 3D industry, fall so low and so quickly? Petis did not respond to requests for comment, and Smith and Mayer declined to be interviewed for this article.

We collected information from various industry observers, today's MakerBot executives, and a dozen former employees of the company. Some introduced themselves, while others wished to remain anonymous.

Within a few years, MakerBot needed to make two successful moves. It was necessary to show millions of people the wonders of 3D printing, and then convince them to shell out more than $1,000 for a machine. She also needed to develop technology that was fast enough to keep customers satisfied. And these tasks turned out to be beyond the strength of the young company.

"MakerBot made a big commitment and was trying to meet a market demand that never came," says Ben Rockhold, who worked for MakerBot for four years as an engineer. In pursuit of the dream of everyone becoming a manufacturer, MakerBot tried to produce printers that were both inexpensive and attractive, but they never succeeded.

At a TEDx conference in New York in 2012, Petis said, “When you have a MakerBot, you have a superpower. You can do whatever you need."

You can do whatever you need."

Years passed before someone dared to say that it was not true.

* * *

Early on, the MakerBot-based community flourished around these affordable printers.

The inspiration came from British professor Adrian Bowyer, who started work on the RepRap, a desktop 3D printer in 2005, that used fused deposition modeling to print objects. Bower wanted to create a printer that could print a copy of itself. One RepRap would spawn another by printing parts, and so on. In New York, three friends, having learned about this, came up with their own idea. Can they make a machine that prints the parts needed to assemble RepRap? And the answer was positive. Working at the NYC Resistor hackerspace, Zach Smith, Adam Mayer, and Bre Petis created the CupCake CNC, a machine that could print RepRap parts on demand.

MakerBot Assembly Parts

“The idea was to make a small number of these printers so that people can make their own RepRap, and the first batch sold very quickly,” says Staltz, who has worked for MakerBot since December 2011 to April 2012.

In January 2009, the trio founded MakerBot with a $75,000 investment, of which $25,000 came from Bower and his wife, Christina. The company was supposed to sell CupCake as a DIY kit. By spring, the company was selling CupCake sets for $750 each. “We went out because of MAKE magazine, we got the attention of the media, who really liked the idea, and they talked about it all the time,” says Rockhold.

CupCake was also an open source project. MakerBot released the hardware and software for the machine for free, and those who bought CupCakes made their own corrections and additions, which the company included in future versions of printers. The open project brought together people from inside and outside the company, and they were all looking for improvements. It also served as a good advertisement, and became the basis and attractive side of MakerBot.

“Openness is the future of manufacturing and we are at the beginning of an era of sharing,” Petis told MAKE magazine in 2011. “In the future, people will look back at businesses that didn’t want to share with their customers and wonder how they could work the other way around.”

“In the future, people will look back at businesses that didn’t want to share with their customers and wonder how they could work the other way around.”

MakerBot represented the revolution in the production of things. A single CupCake could create near-exact replicas of itself (with the exception of bolts and other metal parts), as well as replicas of countless other objects. This movement was to evolve from a geeky subculture into a transformative force that would change society.

The demand for CupCakes was so great that the owners of these machines even helped MakerBot print parts for distribution of new sets. Active forums flourished on Google Groups and Reddit, with fans sharing object designs on Thingiverse, a site started by the company that stored files under a Creative Commons license.

Some amateurs have made corrections to CupCakes themselves. Christopher Jansen, user ScribbleJ on Thingiverse, has figured out how to reduce machine noise and improve print quality. Another user, Whosawhatsis?, has developed a more efficient extruder, a component that extrudes melted plastic.

Another user, Whosawhatsis?, has developed a more efficient extruder, a component that extrudes melted plastic.

"Because our project is open source, users know they have the right to hack the code and design," Petis said in an interview in early 2010. “They also know that if they improve the car, they can share that improvement with others and everyone will benefit from it.”

The corporate culture at MakerBot was also open and flexible. The first office in Brooklyn was more like an experimental laboratory. Employees arrived late and left late. One day you could be packing CupCakes, the next you could be checking extruders. Petis answered support questions, popped into the MakerBot Operators Google Group for comments, and occasionally helped employees navigate the complexities of the hardware by encouraging them to do things that would have gotten them fired in a more strict company. On one of his first days on the job, Ethan Hartman wondered if PLA, the plastic used to create 3D objects, would catch fire if it stuck to an extruder. He remembers that Petis grabbed the burner, a piece of plastic, and they took turns trying to light it on the floor.

He remembers that Petis grabbed the burner, a piece of plastic, and they took turns trying to light it on the floor.

“Nobody worked there to put in hours and make a lot of money selling,” says Hartman, who worked as a customer service and then company manager from April 2010 to August 2012. “People worked there because they I liked the idea that open iron could be part of a commercial enterprise.”

A lot of things were allowed in the company. Interested passers-by were not forbidden to enter unannounced and see what was happening. “In the earliest days, there was no clear operational structure. We didn't think we'd be able to support the project as it started to grow, and there was no expectation that the company would ever grow very much,” says Matt Griffin, public relations manager at MakerBot since December 2009to August 2012.

Employees thought it was a dream job and a chance to turn an alternative future into reality - a world where everyone can become a manufacturer. Hartman says that MakerBot being an open source company was the single biggest reason people loved working on it. They agreed to even lower salaries. One person recalls that his salary at MakerBot was $22,000 less than at his previous job. But working for the company was exciting. They had to turn the market on their own terms.

Hartman says that MakerBot being an open source company was the single biggest reason people loved working on it. They agreed to even lower salaries. One person recalls that his salary at MakerBot was $22,000 less than at his previous job. But working for the company was exciting. They had to turn the market on their own terms.

In September 2010, MakerBot began selling the Thing-O-Matic, their second 3D printer, as a kit for $1,225 (or $2,500 for the assembled version). By that time, many people were already using CupCakes to create various things, such as an owl-shaped headphone winder or 3D puzzles. Thing-O-Matic upped the ante. A Texas school used it to make chess pieces that looked like the landmarks of San Antonio and then sell them for $150. Petis appeared on The Colbert Report and printed a bust of Stephen Colbert on Thing-O-Matic, which is still available for download from Thingiverse. MAKE magazine compared the appearance of Petis with "a five-minute infomercial and commercial" and rejoiced noisily - they say, "who in the audience would not want to buy one for themselves?".

In the following years, trinkets were replaced by more serious undertakings, such as a 3D-printed prosthetic arm. It seemed that the vision of Petis, described by him in 2009, was being realized. People printed the objects they needed. “At first, the common theme was that ‘We want to change the world.’ The democratization of production is a phrase we used both inside and outside the company,” says a former member of the company's web team, who has worked there since September 2010.

The company has kept this spirit alive. MakerBot was the place where everyone went to meetings, and employees had the ending “bot” at the end of their formal position. Andrew Pelkey was hired in the second week of March 2012 to write blog posts, copywrite and oversee social media posts. But he says that he was not a writer, but a “bot” writer (WriterBot).

The Wire's then-CEO Chris Anderson and Bre Petis, 2010, New York

The classic startup mindset is: fail fast, find solutions, iterate, build fast, release. Petis called it "the cult of the job done" and listed the principles on his blog. One of them: “A mistake is considered a done deal. Make a mistake."

Petis called it "the cult of the job done" and listed the principles on his blog. One of them: “A mistake is considered a done deal. Make a mistake."

Petis was proficient in building a community of followers online. Fans adored him, he was an affable, admirable person who loved to create something and explore what 3D printer lovers created. In his talk at Ignite NYC, he showed a photo of a working whistle, designed by a user in Germany and printed out by a New Yorker. “We invented teleportation. Show me how to get a whistle from Germany to New York without a rocket,” he joked gleefully. The audience picked up his laughter.

And over time, it was Petis, not Mayer or Smith, who became the public face of the company. In the 2014 documentary Print the Legend, Petis recalls a conversation with the co-founders when they compared him to another tech prodigy. “You have to be Steve Jobs,” Petis recalls on camera, and then says that he himself wanted to be the equivalent of Steve Wozniak.

But Petis was doing a great job at MakerBot as Jobs, and customers were picking up the Thing-O-Matic and CupCake that MakerBot was selling on Father's Day 2011 for a special price of $455. “The typical MakerBot user was someone who recently found out that 3D printers are cool. And when they found out that they could be bought for $1,000 or less, it completely turned their heads,” says Hartman.

It wasn't just tech journalists who wrote about MakerBot anymore. Rolling Stone wrote about Thing-O-Matic. CBS Evening News wondered if the ubiquity of MakerBots would give us the ability to create anything. The New York Times printed Thing-O-Matic diagrams.

By August 2011, MakerBot had sold 5,200 printers. It received $10 million in investments that month — from the Foundry Group, Bezos Expeditions and others — and began to grow by adding another office in Brooklyn. By autumn, MakerBot employed 70 people.

The excitement grew, but early employees felt that change was inevitable. “Collecting investments is what got people excited. The attitude has changed to 'Now we have to show dramatic growth and start growing the company at a tremendous rate',” says Hartman.

“Collecting investments is what got people excited. The attitude has changed to 'Now we have to show dramatic growth and start growing the company at a tremendous rate',” says Hartman.

In a post about the investment, Petis wrote that the investment and active hiring was necessary to "democratize manufacturing and make 3D printing easier for everyone!".

* * *

The company knew it needed a simpler, plug-and-play printer to attract people other than hackers. “The kits were difficult to assemble. People needed pre-assembled things that just work,” says Hartman.

So MakerBot decided to develop and present at the 2012 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) their new "MMM" product, the Mass Market MakerBot. It was planned that the cost of the MMM would be comparable to the cost of a game set-top box - and no self-assembly. Such a device should have appealed to typical Walmart and office equipment shoppers.

The company secretly orchestrated the development of MMM by opening a subsidiary in China, a "crazy top-secret project" as one former employee called it. Zack Smith, an engineering specialist, became the head of development. He took key engineers from Brooklyn and China.

Zack Smith, an engineering specialist, became the head of development. He took key engineers from Brooklyn and China.

But in September 2011, Petis decided to change the course of the company. He called the members of the R&D team and announced that in three months they should design, build and test another 3D printer, The Replicator. “The Replicator was born because Bre showed up to a meeting, grabbed all the developers in Brooklyn, and said, we need a printer for CES, but didn't say why,” says Rockhold. Boxes of MMM versions arrived in Brooklyn intermittently, but "the rate of printer improvement was very slow," says Rockhold.

CES was approaching, and Pettis wanted to see the printed objects for verification: one the size of a loaf of bread and the other a DeLorean from Back to the Future. Replicator passed the test and became the main number of the company at CES. Its retail price was $1749.

It never became an inexpensive printer, but it still won the "Best Emerging Tech" award at CES. It had a certain charm - the frame of the printer was made of balsa. And it was sold fully assembled. The hardware and software were still open source, so the community could continue to support the project. And besides, the fans themselves could fix possible problems, which made the Replicator a workhorse in their eyes.

It had a certain charm - the frame of the printer was made of balsa. And it was sold fully assembled. The hardware and software were still open source, so the community could continue to support the project. And besides, the fans themselves could fix possible problems, which made the Replicator a workhorse in their eyes.

A few months later, in April 2012, MakerBot ended all operations in China. Zach Smith retired. “There was no way to mention MakerBot China,” says one former employee.

According to Rockhold, people bought the Replicator in "packs". But he says that the printer had serious problems: the heated platforms burned out because the cables did not maintain the desired voltage, and the machine itself was very sensitive to static. If a user who had built up a static charge inserted an SD card with a file to print, the machine could make a loud sound - the sound of the printer being destroyed, or, at best, the sound of an expensive repair.

By that time, MakerBot was not the only printer - and was in danger due to the fact that the company could not release printers cheaper. A month before CES 2012, web developer Brook Drumm raised $831,000 on Kickstarter for Printrbot, which was sold as a build kit and cost just $549. The Cube, a glossy plastic desktop printer from 3D Systems, a serious company specializing in industrial 3D printing, also debuted at CES 2012 for $1,299. A few months later, Solidoodle, founded by former MakerBot COO Sam Cervantes, released a new no-build printer priced at just $49.9.

A month before CES 2012, web developer Brook Drumm raised $831,000 on Kickstarter for Printrbot, which was sold as a build kit and cost just $549. The Cube, a glossy plastic desktop printer from 3D Systems, a serious company specializing in industrial 3D printing, also debuted at CES 2012 for $1,299. A few months later, Solidoodle, founded by former MakerBot COO Sam Cervantes, released a new no-build printer priced at just $49.9.

That same year, analytics firm Gartner made an important discovery. On the "Gartner Hype Cycle" chart, which tracks emerging new technologies through stages from over-enthusiasm and disillusionment to sobering realism, 3D printing was placed at the very top of the peak labeled "peak inflated expectations." In an attached report, Gartner clarified that 3D printing refers to home use of printers. The idea of a consumer technology market for "do-it-yourself manufacturers" has reached the height of the hype.

* * *

In May 2012, MakerBot announced its move to the 21st floor of the MetroTech Center in Brooklyn. It already employed 125 people and was preparing to introduce a new printer, the Replicator 2, to the world. “There are no signs of a slowdown in demand anytime soon,” Petis said at the time. "It won't be long until the MakerBot is as common as the microwave!"