3D printing post processing

3D Print Post Processing - Ultimate Guide

Get more from your 3D prints with smoother surfaces, improved mechanical properties, enhanced aesthetics, and more.

Get an overview of 16 post-processing techniques in this guide or see some real life examples in the ebook and webinar:

SMOOTH SURFACES

Reduce the appearance of print layers and refine surfaces

Strengthen Parts

Reinforce prints for added strength and durability

ADD FUNCTIONALITY

From UV and weather resistance to conductivity and more

AESTHETIC FINISHING

Transform the surface appearance for visually striking parts

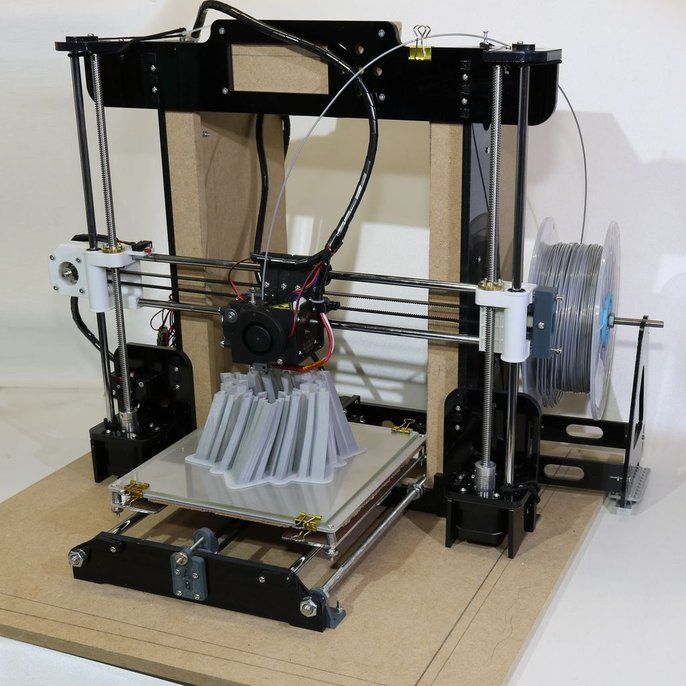

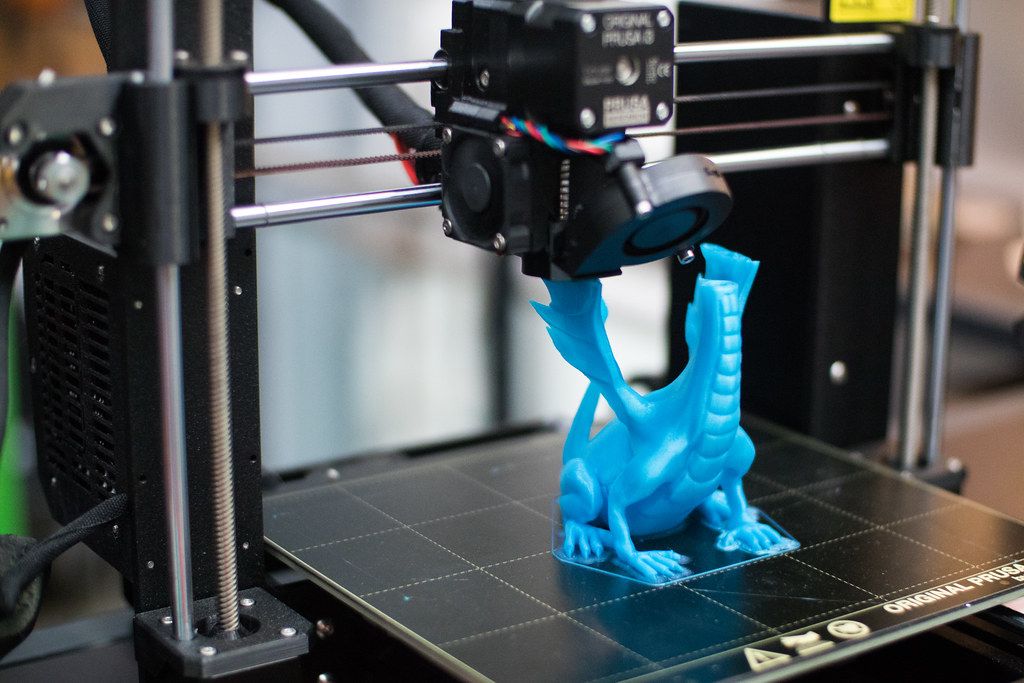

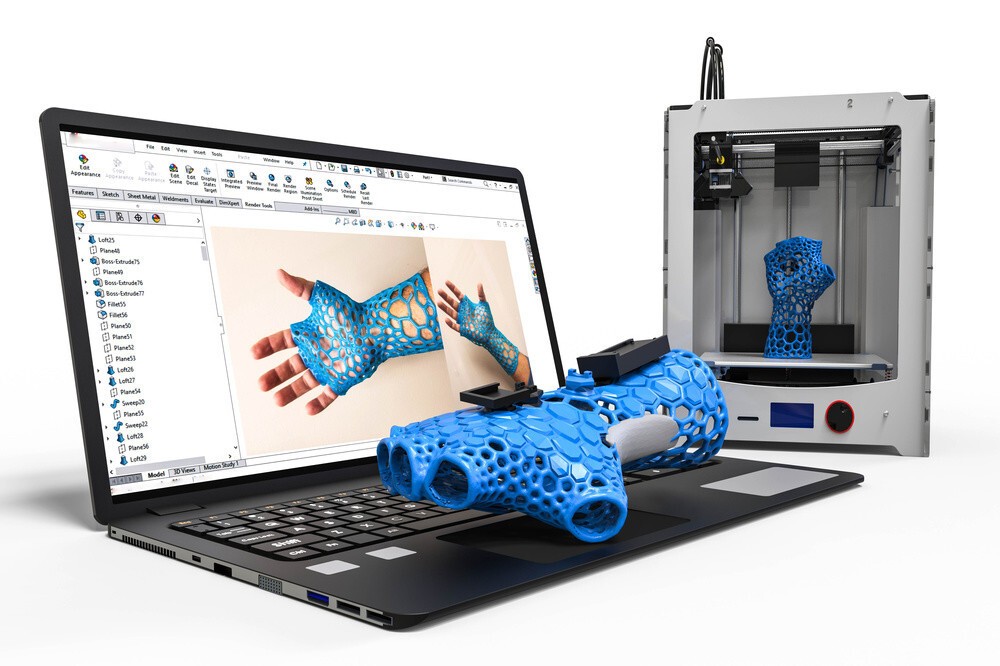

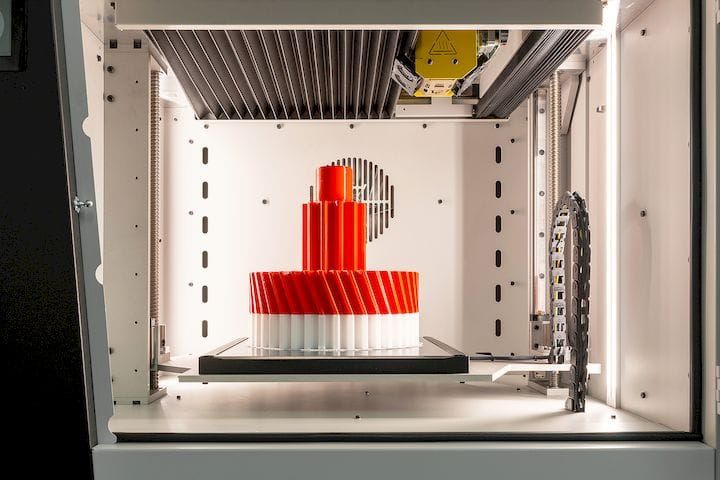

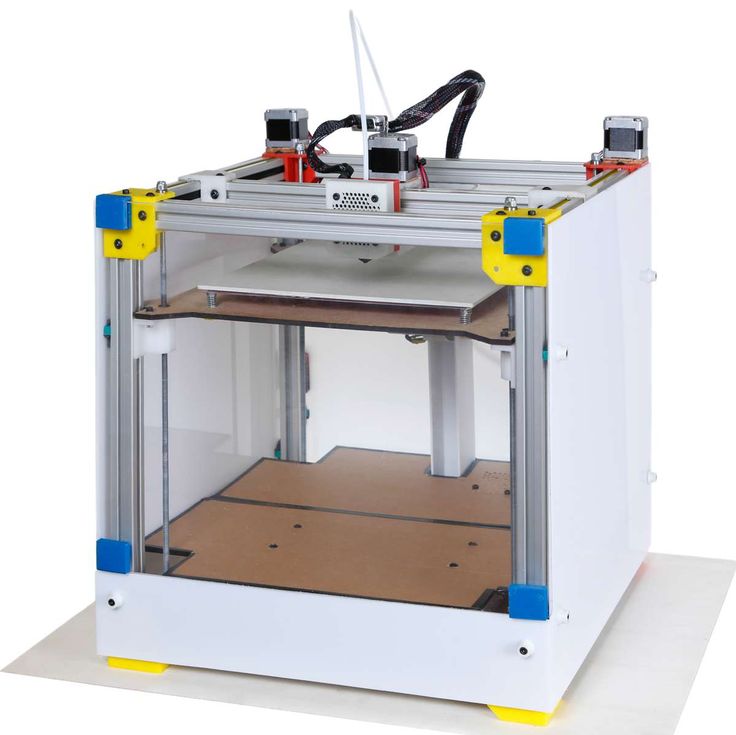

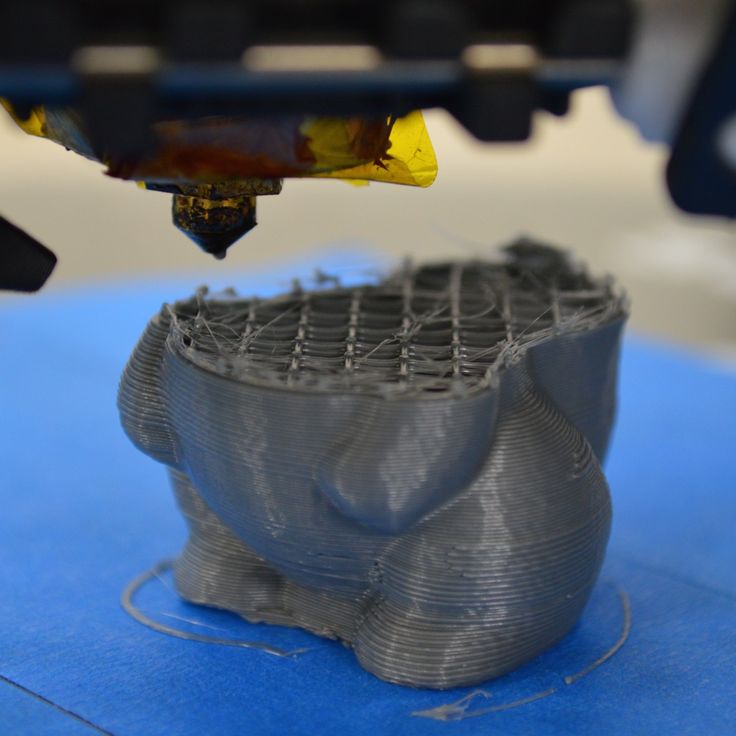

All 3D prints are produced layer by layer, which results in a notched surface texture that is more pronounced with lower print resolutions. If support structures are needed for your part, it may have additional flaws on their touch points. This guide covers the first step to part finishing, support removal, and the three categories of post-processing: Subtractive, Additive, and Material Changing.

Support Removal

Unless your print is optimized for supportless 3D printing, you’ll probably be printing with support structures. These are usually easy to snap off, but even well designed supports will leave behind imperfections where they were once attached. To smooth these areas, it is recommended to post-process the entire part by any number of methods outlined below.

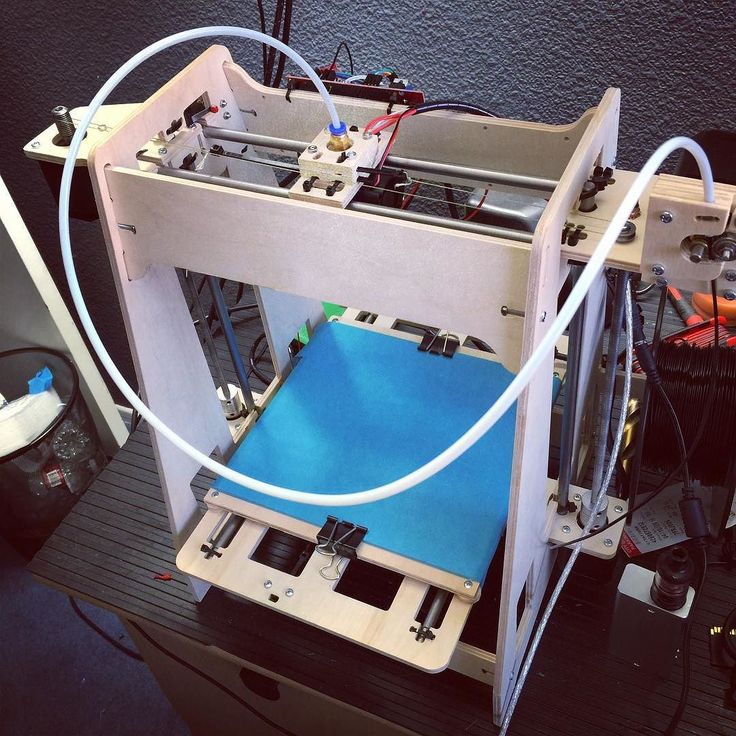

With dual extrusion you can print soluble support structures that disintegrate in water and leave no trace on your part. They’re especially useful when post-processing isn’t otherwise necessary.

SUBTRACTIVE

The most common post-processing category, subtractive post-processing is the act of removing material from the part surface to make it more uniform and smoother.

ADDITIVE

Additive post-processing puts additional material directly onto printed parts. Additive techniques are highly efficient for smoothing parts while adding strength and other mechanical properties.

PROPERTY CHANGING

Neither removing nor adding material, property changing post-processing redistributes molecules of a 3D print. Smoother and stronger parts are achieved with thermal and chemical treatments.

Subtractive Post-Processing Methods

Probably the most common post-processing category, subtractive post-processing is the act of removing some of your part’s material. Usually this is in the form of sanding or polishing a part, but there are a variety of other methods that includes tumbling, milling, abrasive blasting, and chemical abrasive dipping.

Sanding & Polishing- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Both sanding and polishing techniques remove surface layers by rubbing it with an abrasive material. Sanding requires coarser grit sandpaper and sanding tools, while polishing may use finer sandpaper, steel wool, polishing paste, or cloth.

Sanding removes larger blemishes such as support remnants or print irregularities and reduces the visibility of print layers. The sanding process will leave a gritty, although more uniform surface texture, and very course sandpaper will leave surface scratches. Polishing the part after sanding will produce an even smoother surface.

Simplicity and affordability make sanding and polishing the most common methods of post-processing, but both require labor that is time consuming for larger parts and batches. These methods may not be suited for parts with hard to reach cavities.

Tumbling- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

A tumbling machine consists of a vibrating vat containing lubricating fluid and abrasive media, which are specialized stones that wear objects down according to their size, shape, and hardness as they tumble together. A 3D printed part is simply placed into the vat of tumbling abrasive media for specific length of time. Some expertise is required to pair parts with the correct abrasive media and processing time, but when done correctly it is very effective at producing uniform finishes.

A 3D printed part is simply placed into the vat of tumbling abrasive media for specific length of time. Some expertise is required to pair parts with the correct abrasive media and processing time, but when done correctly it is very effective at producing uniform finishes.

Tumbling is largely automated subtractive method that can post-process multiple parts simultaneously, which is useful for smoothing batches of parts. Tumbling vats come in a range of sizes so larger parts can also be processed. Since the abrasive media is constantly in contact with the part, larger pieces do not require longer processing time, but only larger machines with the adequate amount if abrasive media. However, complex shapes may loose detail and sharp edges may become slightly rounded by tumbling.

Abrasive Blasting (Sand Blasting)- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Abrasive blasting, also known as sand blasting, is subtractive post-processing method where abrasive material is blasted onto 3D printed parts at high pressure. For large parts this can be done in an open environment, but smaller parts are typically processed in a containment chamber that collects and reuses the abrasive material. Like other grit-based subtractive methods, there are a range of grits available and grit must be chosen based on part geometry and desired finish. Sand is a frequently used abrasive material, but other small coarse objects such as plastic beads can be used for different results.

For large parts this can be done in an open environment, but smaller parts are typically processed in a containment chamber that collects and reuses the abrasive material. Like other grit-based subtractive methods, there are a range of grits available and grit must be chosen based on part geometry and desired finish. Sand is a frequently used abrasive material, but other small coarse objects such as plastic beads can be used for different results.

Since the abrasive material is smaller than that of tumbling, abrasive blasting is less effective on very rough parts or high layer heights. This method only treats surfaces reachable by the stream of blasted material, so complex geometries and cavities may not be feasible. Additionally, the blasting tool can only treat limited areas at a given time, so this method may be slower and difficult to process multiple parts simultaneously.

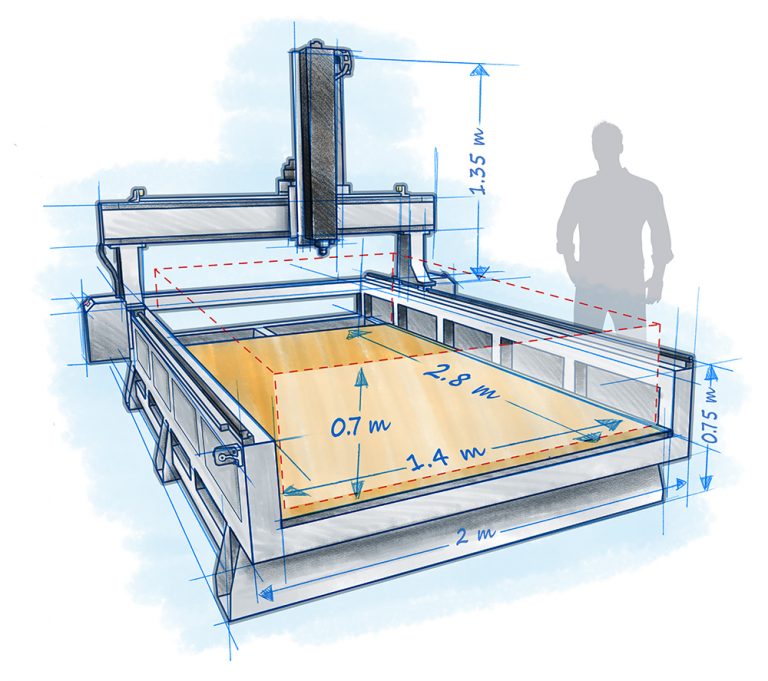

CNC Machining (Milling)- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

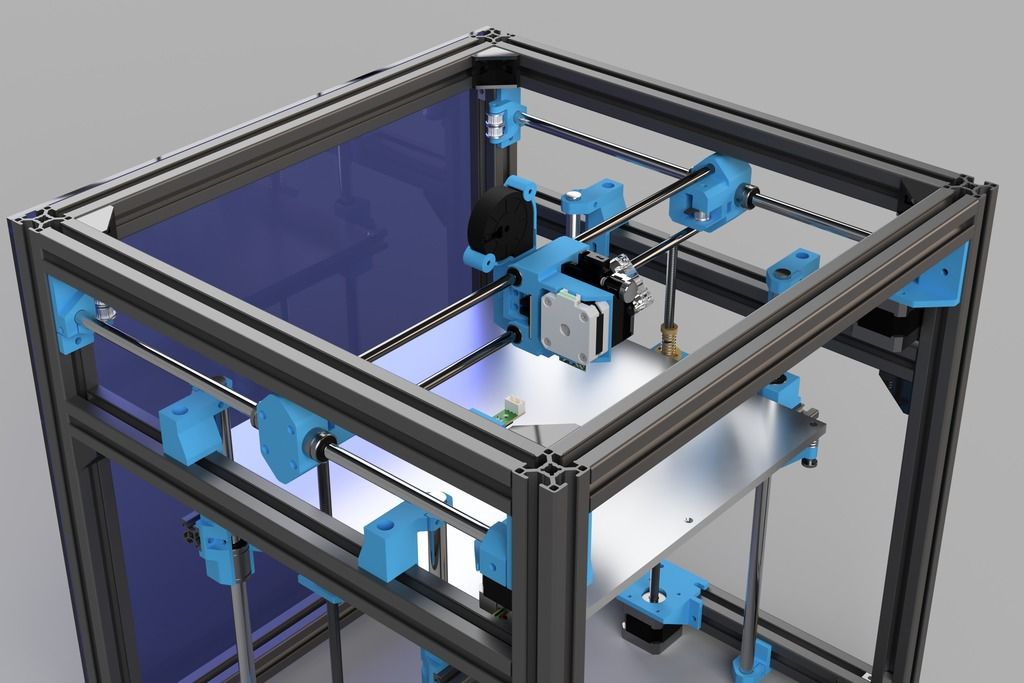

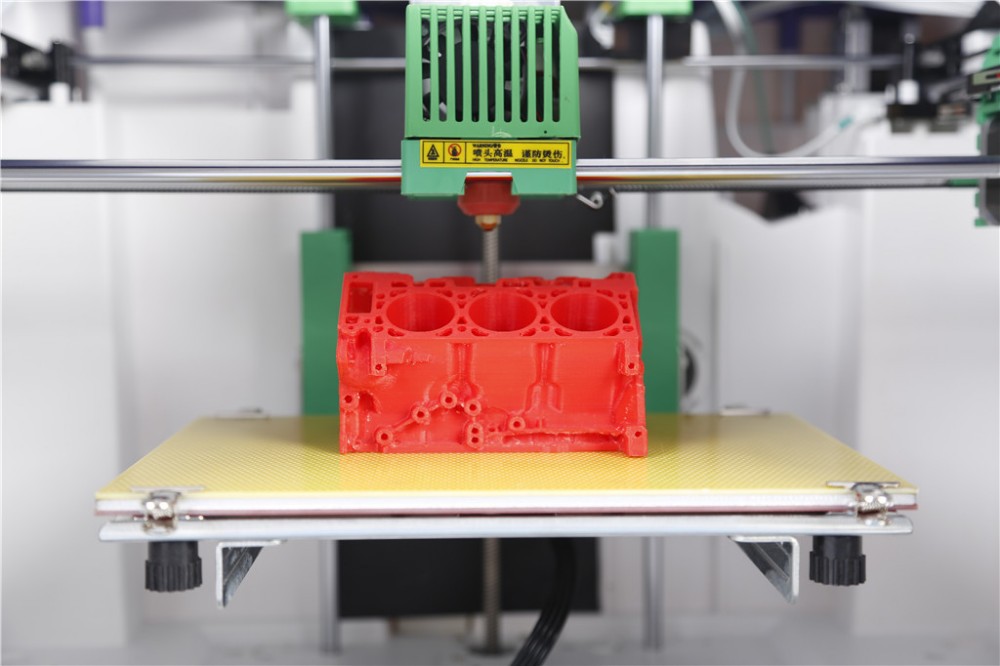

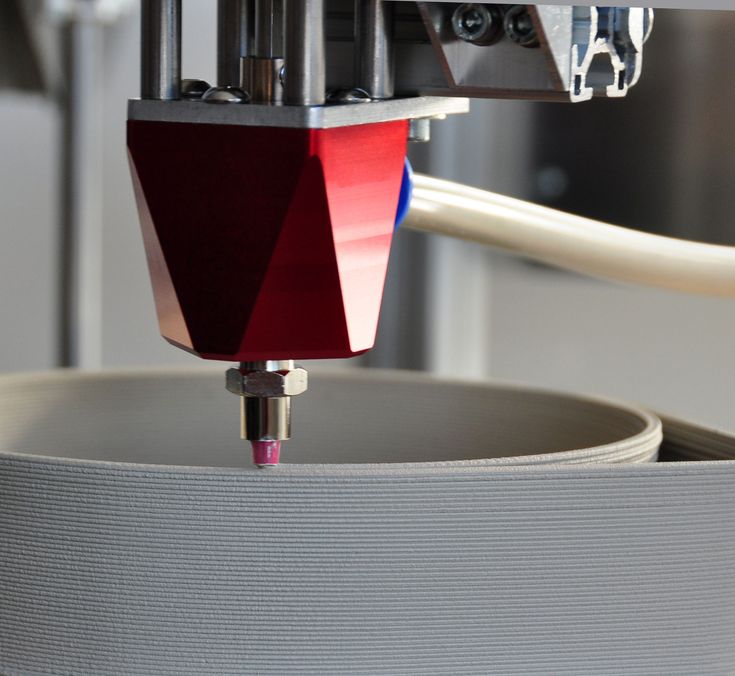

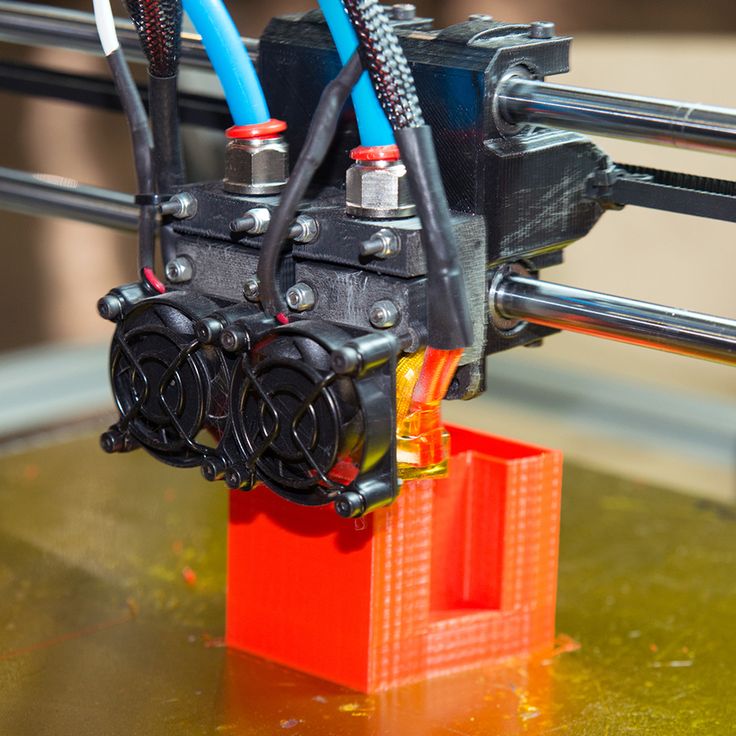

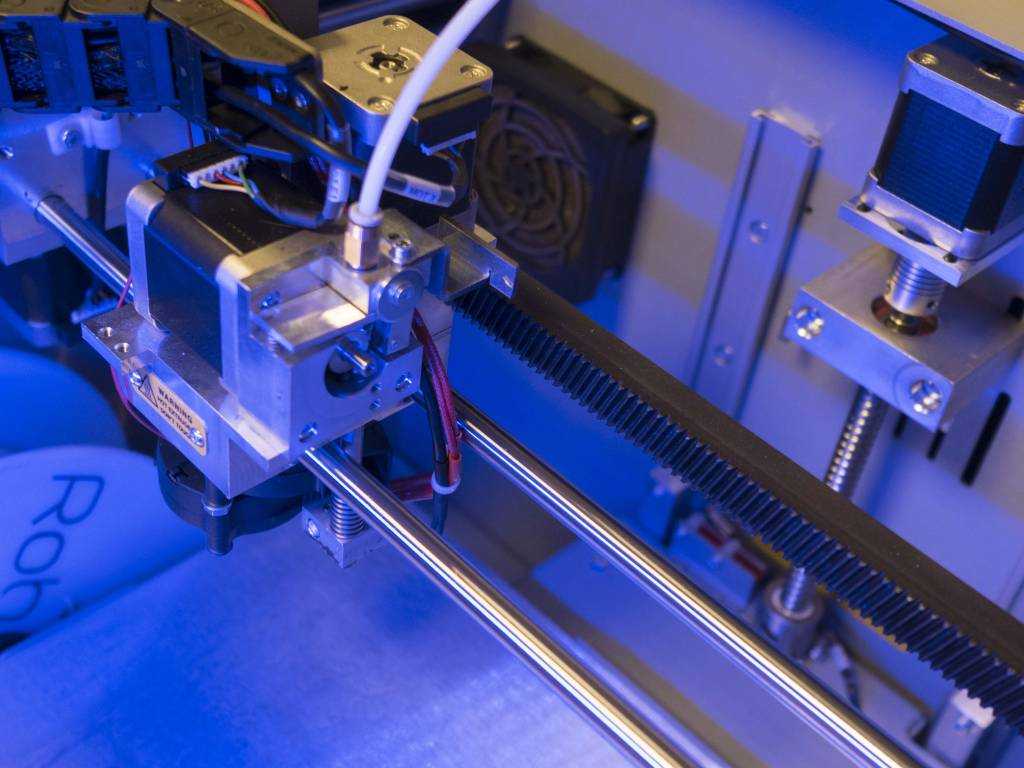

CNC milling, also called CNC machining, is the inverse of 3D printing - it uses a computer-programmable drill moving (and sometime rotating) in three axes to carve out geometries. Like 3D printers, the technology uses “G-Code” to program tool movements, in this case a milling bit rather than a filament extruder.

Like 3D printers, the technology uses “G-Code” to program tool movements, in this case a milling bit rather than a filament extruder.

While CNC machining is considered highly accurate from 0.005” to 0.00005”, it cannot produce certain geometries and wastes material, which is often expensive. Conversely, large-format 3D printing cannot achieve the same accuracy, but can achieve much more complex geometries and wastes very little material.

It is typically not time or cost effective to mill the entire surface of a 3D print and it may be difficult to calibrate the milling tool to the print position. But while these two production methods are seemingly at odds, there are some situations where they may be used together. If a portion of a 3D printed part must be extremely smooth or accurate, that specific area can be milled. Alternately, manufacturers can save material by 3D printing a part in a rough finish before milling it to perfection.

- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Chemical dipping, also called aid dipping, is the process of submerging parts in a chemical bath that eats away the surface. The process involves caustic materials, such as lye, sodium hydroxide, or dichloromethan, and should only be done by experts in facilities with the requisite safety features. The appropriate chemical choice is entirely dependent on the material of the 3D print, as the chemical must be abrasive to the print material.

Some expertise is required to determine how long parts should remain submerged: too brief and the part will not be sufficiently smooth, too long and it could be ruined entirely. Some care should be taken to avoid air bubbles trapped inside the 3D print as they will prevent the chemical treatment of the surface. Typically the submerged part is gently moved to agitate the chemical bath and release any air bubbles.

The process is ideal for complex geometries as the chemical bath treats all surfaces of submerged parts simultaneously. However, the size of the chemical dipping container determines the limited part dimensions of treatable prints.

Additive Post-Processing Methods

Additive post processing puts additional material directly onto printed parts and is highly efficient for smoothing parts while adding strength and other mechanical properties. There is a wide spectrum of methods from filling to priming, coating, metal plating, and more.

Filling- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Filling is a surface treatment that uses a thick adhesive compound, typically a paste, to fill in notches like the tiny gaps between layers of a 3D print. It is commonly used as a first step before sanding or additional additive layers. A wide range of fillers from pastes to sprays are available in many materials from light spackle to 2K resins.

Paste fillers, like wood fillers or household spackle, are usually the most accessible option. They are simply spread over the part surface and can be easily smoothed with light sanding. Spray fillers are easy to apply but provide only a thin surface covering, resulting in a rougher coating. More robust, but more advanced options are resin fillers that must be cured by one of two methods: mixing with a hardener or UV exposure. Resins are available with various viscosity, cure speeds, and advanced features like UV and a high heat deflection temperature. For some UV-cured fillers leaving parts in the sun may be sufficient, but others will require a specialized UV chamber.

When using any kind of resin cover skin, wear gloves, and keep the working space well ventilated. Ensure you’re familiar with the requirements of your filler or coating before applying it to a part as this may drastically change the time or equipment required for post-processing.

- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Primers prepare 3D printed parts for the addition of subsequent layers by pre-treating the surface for better adhesion. They are far less viscous than fillers and may only smooth very small surface imperfections, so their main function is adhesive surface preparation. Primers are available in spray or brush form, but spray primer may produce a more even coating.

To prime a part most effectively, the imperfections and layers notches should first be reduced by other post-processing methods such as sanding or filling. Ensure that your primer is made for plastic adhesion and is suitable for additional materials you intend to apply later. Leave the primer to set for 24 hours or as otherwise directed.

Brush Coating- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Liquid coatings vary widely in material such as paint, varnish, resin, or even plastic. While there are several application methods, brush coating is the simplest way to smooth unique or small batches of 3D printed parts. Although the surface smoothness may be inconsistent due to brush strokes, choosing a material with the proper viscosity can avoid these surface irregularities.

While there are several application methods, brush coating is the simplest way to smooth unique or small batches of 3D printed parts. Although the surface smoothness may be inconsistent due to brush strokes, choosing a material with the proper viscosity can avoid these surface irregularities.

For a robust and smooth surface apply a 2K resin, which is a two-component mixture of resin with a hardener. When combined, the mixture created an exothermic chemical reaction that cures the resin over a given amount of time. There is a huge range of resin products for a variety of uses: laminating resins for thin surface applications, casting resins for larger volumes, fast and slow curing resins, and resins with additives (like aluminum, for example) for additional performance enhancement such a temperature, UV, or chemical resistance. To achieve the smoothest surface when brush coating, use a resin with an appropriate “self-leveling” viscosity that will even out brush strokes without material dripping off the part. There are resin products specifically formulated for 3D prints that can achieve very smooth surfaces after one coating.

There are resin products specifically formulated for 3D prints that can achieve very smooth surfaces after one coating.

When brushing other materials such as paint or varnish it may be more difficult to avoid brush strokes, but many coatings can be sanded after drying to achieve a smoother surface. It is also possible to apply an additional coating of another material, 2K resin for example, to achieve a smoother final result.

Spray Coating- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

A wide-ranging and scalable post-processing technique, spray coating a offers a number of viable methods ranging from DIY projects to robotic automation at an industrial scale. Spray coatings are available in a huge variety of materials such as paint, varnish, resin, plastics, and rubbers, just to name a few.

The simple approach for DIY projects is a spray can of chosen material applied in a ventilated/outdoor space. Since this method typically results in minimal surface smoothing, it is recommended to sand the part first and apply several spray coats. Applying a spray primer may help the spray coating adhere to the part. Spray paint can be used for aesthetic enhancements and spray varnish can protect the surface against chipping, wear, and UV damage.

Since this method typically results in minimal surface smoothing, it is recommended to sand the part first and apply several spray coats. Applying a spray primer may help the spray coating adhere to the part. Spray paint can be used for aesthetic enhancements and spray varnish can protect the surface against chipping, wear, and UV damage.

For large volume or industrial spray coating applications, a robotic arm fitted with a spraying tool head can apply a wide range of coatings to a 3D printed part. The application typically takes place in spray booth with an adequate air filter. This method allows a wider range of materials, including 2K spray coatings, primers, paints, and more, and results in higher application precision and uniformity. A robotic arm will speed up the processing time and make high volume post-processing feasible at an industrial level.

Spray coating is most suitable for finishing large parts, rather than other additive methods such as dipping, foiling, or powder coating. The later methods all require a machine or vat that can contain the entire part, whereas spray coating is only limited by the size of the room in which it is done.

The later methods all require a machine or vat that can contain the entire part, whereas spray coating is only limited by the size of the room in which it is done.

- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

In foiling, or vinyl wrapping, an adhesive foil made of light metals or plastic is wrapped onto an object, often preceded by priming. Commonly know for wrapping vehicles, vinyl wrapping can also be applied to 3D printed objects with a suitable material. Depending on the material, the foil may increase heat and stress resistance, but is often applied for aesthetic enhancement like smoothing and surface quality.

The difficulty of this post-processing technique varies with the size and complexity of your part. A simple geometry, like the gently curved side panel of a vehicle, is relatively easy to foil, but complex shapes are more difficult with some being impossible to foil.

Wrapping is particularly suitable to apply detailed surface designs to 3D printed parts. Adhesive foils come in a wide range of colors and patterns, as well as custom-printed designs. Foil can be applied by hand, stretching the material over objects to ensure no imperfections like air bubbles remain. Heat guns are often used in the process to make application easier and avoid imperfections. Vacuum foiling will automate the process for faster, precise results to ensure the material wraps around the part as perfectly as possible.

Foiling is usually not suitable for complex parts as the foil will be extremely difficult to apply uniformly and inside cavities.

Dip Coating- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

When dip coating, a part is submerged into a vat of material such as paint, resin, rubber, etc. and removed after a specified time, resulting in an even surface distribution. The part can be redipped multiple times for a thicker coating and smoother surface. Dipping can be used for aesthetic finishing and functional enhancement like increased strength and resistance to heat, chemicals, weather, etc.

The part can be redipped multiple times for a thicker coating and smoother surface. Dipping can be used for aesthetic finishing and functional enhancement like increased strength and resistance to heat, chemicals, weather, etc.

The typical dipping process is comprised of five stages:

- Immersion: The 3D printed part is immersed in a vat of material at a constant speed.

- Start-up: The part remains submerged for a specified time for the coating to adhere.

- Deposition: The part is removed at a constant rate as a thin layer of the material is deposited.

- Drainage: Excess material will drip off of the part surface back into the vat.

- Evaporation: As the coating sets the solvent evaporates from the material, leaving a solid film.

Hydro dipping, also known as water transfer printing is a unique method for applying detailed designs onto a 3D print. The part is submerged in a vat of clean water that has a layer of material floating on its surface, typically a water soluble printed film or an oil based paint. As the part passes through the floating layer, the film or paint adheres to the part’s surface. The surface tension of the water ensures that the film curves around any shape. Best results are achieved when parts with gently curving geometries.

As the part passes through the floating layer, the film or paint adheres to the part’s surface. The surface tension of the water ensures that the film curves around any shape. Best results are achieved when parts with gently curving geometries.

Dip coating is suitable for complex geometries and requires some expertise about the coating material used. The size of the vat determines the dimension of treatable parts. Large prints may not be feasible, although batch processing is possible for smaller parts.

Metal Plating- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

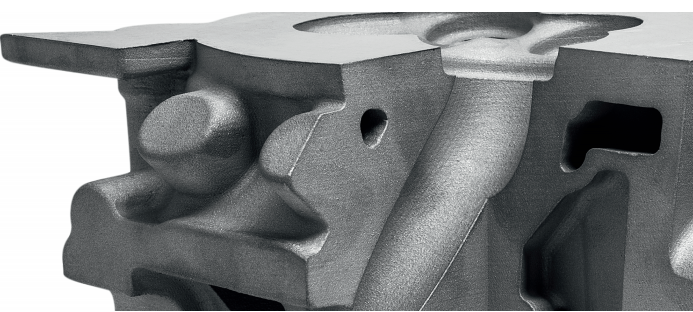

Metal plating is a chemical process where a layer of metal is bonded to a 3D printed part. It is a highly effective method to create 3D printed objects with high resistances to heat, impact, weather, and chemicals, or to create conductive parts.

The first step in metal coating plastic parts is "electroless plating" that metalizes the surface of the print, priming it for proper metal plating. This process ranges from special metal paints that are simply brushed or sprayed onto the part, to industrial processes involving numerous steps of cleaning, etching, neutralizing, activating, etc. Typically, this first layer is copper or nickel, although silver and gold are also possible.

This process ranges from special metal paints that are simply brushed or sprayed onto the part, to industrial processes involving numerous steps of cleaning, etching, neutralizing, activating, etc. Typically, this first layer is copper or nickel, although silver and gold are also possible.

In the second step in metal plating, the metalized 3D print is submerged in a bath for a specific length of time to deposit a wide range of metals like tin, platinum, palladium, rhodium and even chrome. In electroplating, the part is placed in a galvanic bath that deposits a thin metal layer from 1 - 50 microns thick. Anode and cathode ions pas through the liquid and adhere to part in microscopically fine layers. Additional metal plating processes can build up the metallic surface thickness or deposit a different metal material.

When using a metal-acid solution, parts are submerged in the liquid solution for a specific duration, depending on the desired plating thickness. A chemical reaction attracts and adheres the metal ions to the surface of the part. Once removed from the bath, the part can receive a protective coating to prevent oxidation, corrosion, or tarnishing. A heat treatment may be used to strengthen the metal layer adhesion and prevent brittleness.

A chemical reaction attracts and adheres the metal ions to the surface of the part. Once removed from the bath, the part can receive a protective coating to prevent oxidation, corrosion, or tarnishing. A heat treatment may be used to strengthen the metal layer adhesion and prevent brittleness.

Metal plating typically works well for complex parts and can produce a range of surface qualities, smoothness, and mechanical enhancements. However the process requires many stages and expertise.

Powder Coating- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

When powder coating, also known as rotational sintering, a part is heated and rotated within a cloud of the powdered plastic. As the powder compound meets the heated part, it is melted to the surface to produce a fine coating. Due to surface tension while spinning, the adhered powder produces a homogeneous, non-porous layer about 400-microns thick. The surface is typically not glossy smooth, but rather has a fine matte texture caused by the plastic cloud particle size, typically 2-50 microns.

The surface is typically not glossy smooth, but rather has a fine matte texture caused by the plastic cloud particle size, typically 2-50 microns.

Powder coating is a common method for protecting large metal components, but it is difficult to achieve with 3D prints. In traditional powder coating, the metal parts experience temperatures up to 200 °C, but the lower temperature resistance of most 3D printed plastics greatly limits use of this post processing method. When possible, powder coating is highly efficient for batch production with uniform surfaces, although cavities may be difficult to post process.

Property Changing Post-Processing Methods

Neither removing nor adding material, property changing post-processing redistributes molecules of a 3D print. Smoother and stronger parts are achieved with thermal and chemical treatments.

Local Melting- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Local melting is an easy way to reduce the appearance of surface scratches from damage, support removal, or abrasive post-processing like sanding. Rough surfaces are particularly visible on dark colored 3D prints, which appear to be a white-ish color. Using a heat gun set to high heat, quickly pass hot air over the area requiring treatment keeping the heat gun 10-20 cm away from the part. Within seconds, the surface will melt to resemble the original print surface quality. A heat gun can also remove strings from travel moves during printing. Using the same method as described above will melt and shrink the strings. If the strings are large, small remnants may cling to the part, but are often easily removed by brushing or clipping them off.

Rough surfaces are particularly visible on dark colored 3D prints, which appear to be a white-ish color. Using a heat gun set to high heat, quickly pass hot air over the area requiring treatment keeping the heat gun 10-20 cm away from the part. Within seconds, the surface will melt to resemble the original print surface quality. A heat gun can also remove strings from travel moves during printing. Using the same method as described above will melt and shrink the strings. If the strings are large, small remnants may cling to the part, but are often easily removed by brushing or clipping them off.

This method is not suitable for deep scratches as it is only effective for light surface roughness. It also can easily deform the part, so take care to limit the time an area is heated. Best results are achieved by sweeping hot air across the surface for several seconds. Local melting is not recommended for overall surface smoothing, but for easy and effective for smoothing small defects and scratches.

- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

Annealing is the process of heating a print to reorganize its molecular structure, resulting in stronger parts that are less prone to warping. Untreated 3D prints have an amorphous molecular structure, meaning that the molecules are unorganized and weaker. Being a poor heat conductor, the extruded plastic cools quickly and unevenly during the printing process causing internal stresses, particularly between print layers. These stress points are most prone to breakage.

To strengthen the part at its molecular level, it is heated to its glass transition temperature, but below its melting point. Achieving the glass transition temperature allows the molecules to redistribute into a semi-crystalline structure without melting the part to the point of deforming. Glass transition and melting temperatures vary between materials and some expertise is required to heat parts to the correct temperature for the proper length of time. 3D prints will shrink during the annealing process, which can be corrected by increasing the original printing dimensions accordingly.

3D prints will shrink during the annealing process, which can be corrected by increasing the original printing dimensions accordingly.

- DIFFICULTY

- SMOOTHNESS

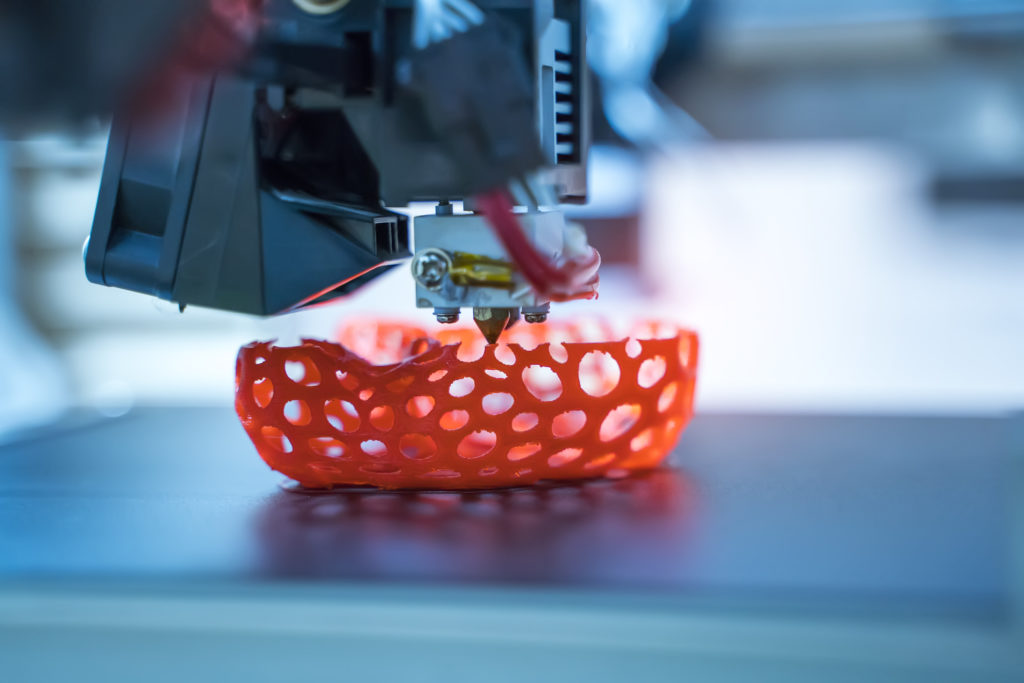

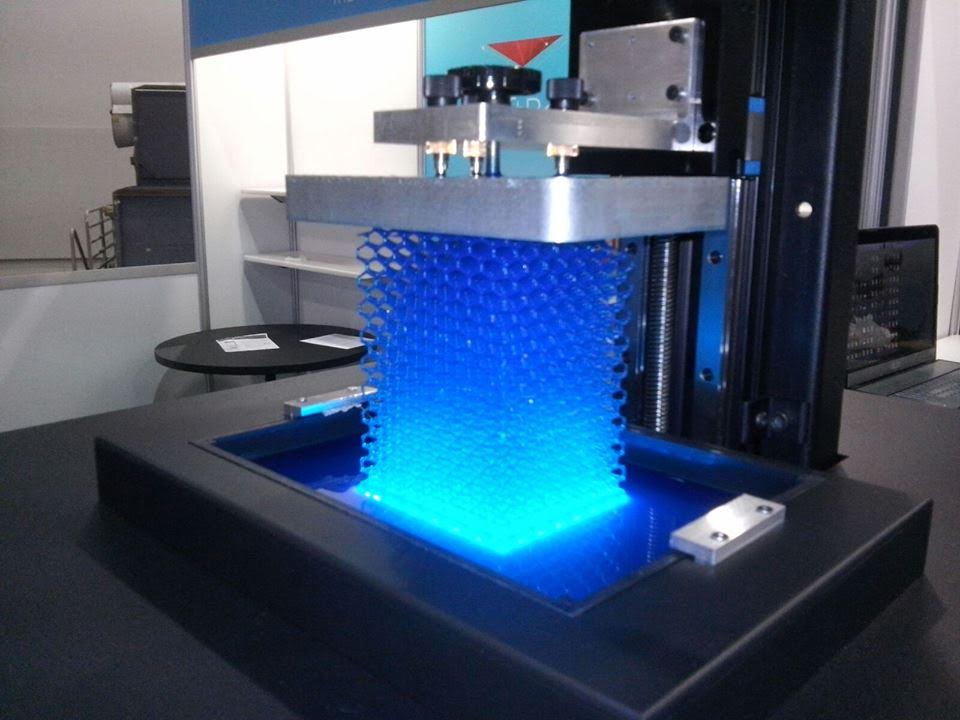

Vapor smoothing is chemical process of smoothing 3D prints in which parts are exposed to vaporized solvents in an enclosed chamber. Similarly to chemical dipping, the correct solvent must be used in correspondence with the 3D print material. The cloud of solvent dissolves the surface of the print, while its surface tension redistributes the dissolved material resulting in a smoother finish. Unlike chemical dipping, no material is actually removed from the part.

Solvents can either be heated to a gaseous state or vaporized by ultrasonic misting. The 3D print is exposed to the vaporized solvents for a specific length of time: too short and the part is not adequately smoothed, too long and the part can deform and become brittle. Most suitable solvents are caustic and combustible, and therefore require extreme levels of caution, adequate chemical containment and disposal, and should only be handled by qualified persons.

Most suitable solvents are caustic and combustible, and therefore require extreme levels of caution, adequate chemical containment and disposal, and should only be handled by qualified persons.

Many vapor smoothing machines are available for use with a variety of solvents suitable for different print materials. These machines make the process automated and much safer, but most can only treat smaller parts due to the chamber's limited dimensions.

Post-Processing eBookFor real life industrial examples, download our free eBook Post-Processing for FFF Prints and see this webinar about post-processing techniques.

The eBook explores the three types of FFF post-processing techniques: 1) Material Removal, 2) Material Addition and 3) Material Property Change. Also, learn more about how various techniques like high resolution tumbling, resin coating and aluminum plating are transforming 3D printed parts.

3d Printing Post Processing FAQs

What is 3D printing post-processing?

Once the printer has finished printing, there may still be some work to do on the printed piece. For example, many shapes require supports to print properly. Removing those is a post-processing task. Some people might want to sand or put a finish layer onto a piece. Resin, as opposed to filament, based prints need to have any uncured resin washed off and final curing under UV light.

3D printing post processing is used to enhance the surface properties of prints in many aspects to deliver improved mechanical performance and aesthetic appearance. By improving these key surface characteristics, post processing widely extents the range of use cases and applications across all industries. 3 types of post-processing techniques can be applied to fused filament fabrication (FFF) prints:

- Material Removal

- Material Addition

- Material Property Change

How do you post process PLA 3D prints?

Almost every 3D print requires some sort of post-processing after it’s printed.

Usually this involves 3 steps:

- Removing support structures

- Sanding or polishing

- Painting or coating

What is the most critical step in the post processing process of 3D printing FDM parts?

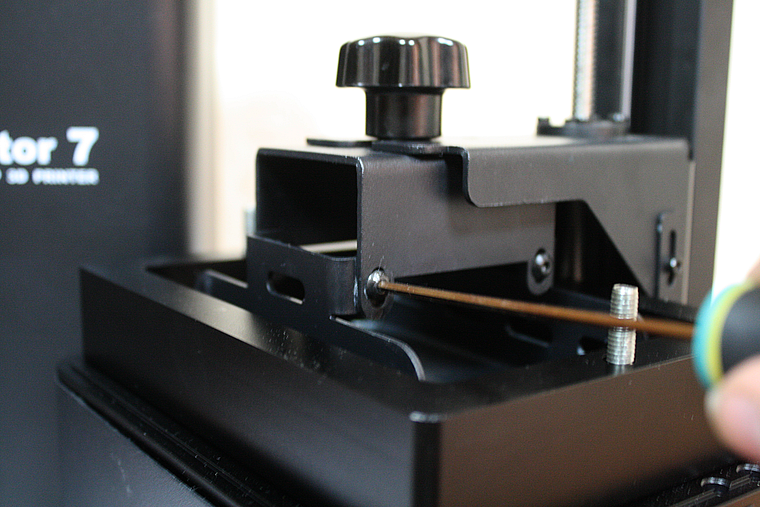

When post processing your 3d printed part, there are 2 steps that are most critical:

- Removing the part from the print bed

- Removing the support structures from the part

In both steps you need to be careful, not to break your 3d printed part. To lower these risks, you can try using flexible print beds and water-soluble support material.

How do I complete FDM parts?

When producing your FDM part, often the finished look matters just as much as the functionality. There are 4 ways to complete FDM parts.

- Remove any support structures

- Smoothing your print

- Filling the gaps

- Painting your part.

Can acetone smooth PLA?

When PLA and acetone smoothing works, it's due to other materials added to the PLA. Most PLAs and similar non-acetone-dissolving 3D printer filaments cannot be smoothed the same way. That's because PLA in its pure form is not reactive to acetone.

Most PLAs and similar non-acetone-dissolving 3D printer filaments cannot be smoothed the same way. That's because PLA in its pure form is not reactive to acetone.

Do I need to cure 3D prints?

It is necessary to cur SLA prints; you don’t have to cure FDM prints. Even though cleaning off any uncured resin is a great start, the step that really brings out the quality of your 3D print is the curing . A high wavelength UV light has the intensity to cure the entire part, it just takes longer for thicker, more solid parts.

Post-processing in 3D printing – Beamler

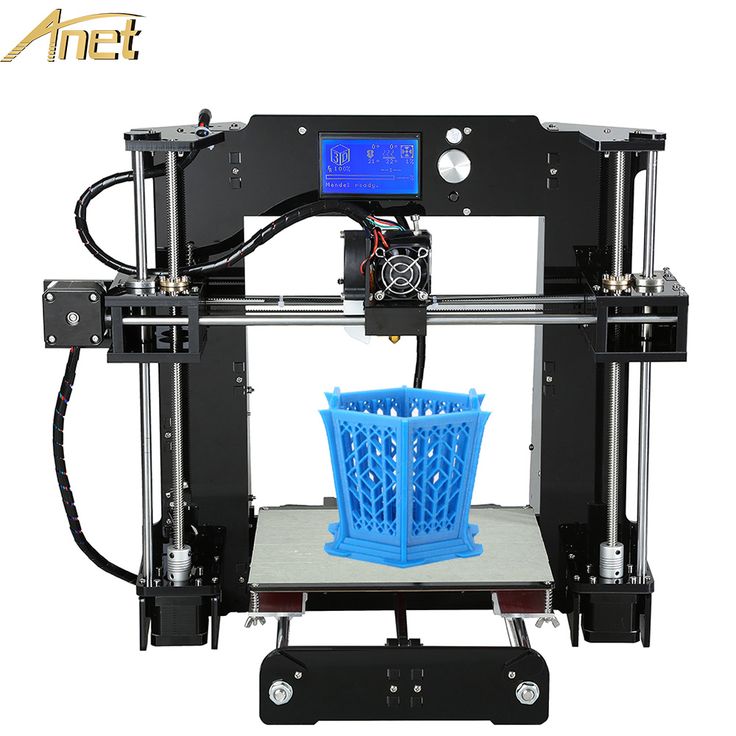

Post-processing is an often overlooked part of the 3D printing process. As the additive manufacturing market moves from prototyping to end part production geared to consumer markets, the look and feel of 3D printed products is becoming increasingly more important. That is where post-processing 3D printed parts comes in.

What is post-processing in 3D printing?

Parts manufactured with 3D printing technologies usually require some degree of post-production treatment. This important step of the 3D printing process is known as post-processing. In short, post-processing in 3D printing refers to any process or task that needs to be performed on a printed part, or any technique used to further enhance the object. Think of it as a finishing touch to treat and refine parts that come out of a 3D printer. The options for post-processing 3D printed parts include removing support or excess material, washing and curing, sanding or polishing a model to painting or colouring.

This important step of the 3D printing process is known as post-processing. In short, post-processing in 3D printing refers to any process or task that needs to be performed on a printed part, or any technique used to further enhance the object. Think of it as a finishing touch to treat and refine parts that come out of a 3D printer. The options for post-processing 3D printed parts include removing support or excess material, washing and curing, sanding or polishing a model to painting or colouring.

Costs of post-processing 3D printed parts

Post-processing can be costly, especially when it is done by hand. Manual post-processing is labour intensive and is not scalable. It will also become unsustainable in large series production.

The cost of post-processing can amount to almost one third of the production cost of a 3D printed model. According to the 2018 Wohler’s report, 27% of the total costs of producing a model can be attributed to post-processing related costs, which include the costs of part breakage.

Luckily, the recent development of various post-processing systems means that the task of finishing 3D printed parts can be automated and, as a consequence, it will bring down the costs.

Different companies are developing post-processing equipment to automate the process. Some of these companies, such as DyeMansion, are focused on post-processing machines only. Others, like Carbon and FormLabs, are 3D printer manufacturers that are adding post-processing systems to work seamlessly with their printing set up.

So, what are the different post-processing techniques available?

We can identify 5 steps in post-processing, although not all steps are required for all projects:

- Cleaning

- Fixing

- Curing or hardening

- Surface finishing

- Colouring

Also, beware that the post-processing technique can vary depending on the printing process used to create the model.

1. Cleaning

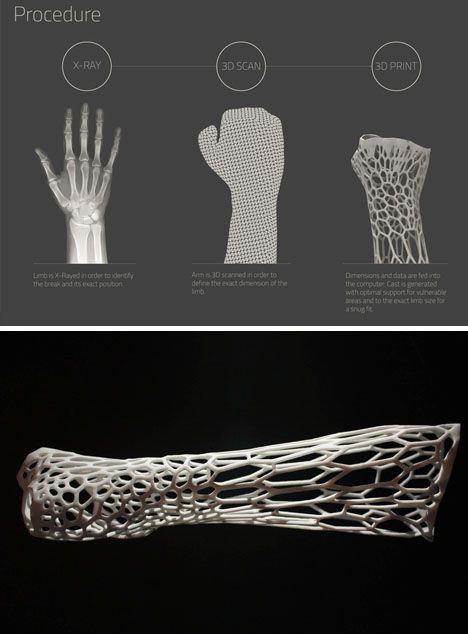

a) Removing support material (FDM and Material Jetting)

When printing models with overhang on FDM or other material jetting technologies, support structures that hold up the overhanging features are needed.

These support structures can be printed using the same material as the one with which the model itself is printed. But when the machine allows for printing with multiple materials, special support material can be used. Nonetheless, every time a support structure is required, there will be some post-processing involved.

There are two types of support material: soluble and insoluble (usually the latter is the same material the model is printed with).

Insoluble material is relatively strong and can only be removed using tools as knives or pliers. This has to be done carefully and there exists the risk of damaging the model, or inadvertently removing small features.

When using soluble support material, there is a lower risk of damaging the model. The support structures can be dissolved in water or with a chemical called Limonene. Examples of soluble materials are HIPS (used as a support with ABS material) and PVA (used as a support with PLA material).

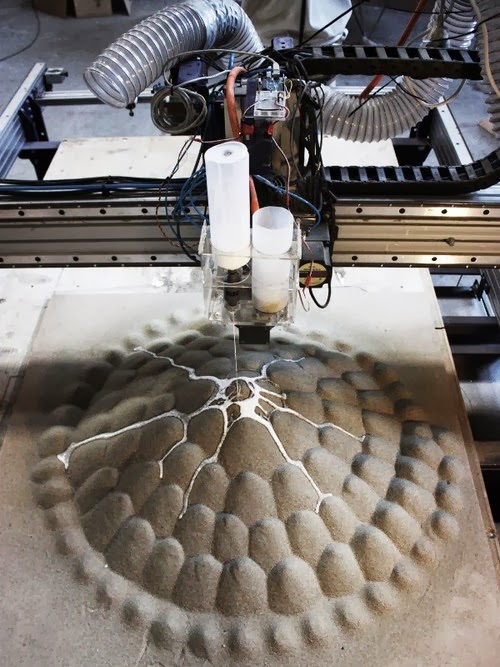

b) Powder removal (SLS and Powder Bed Fusion)

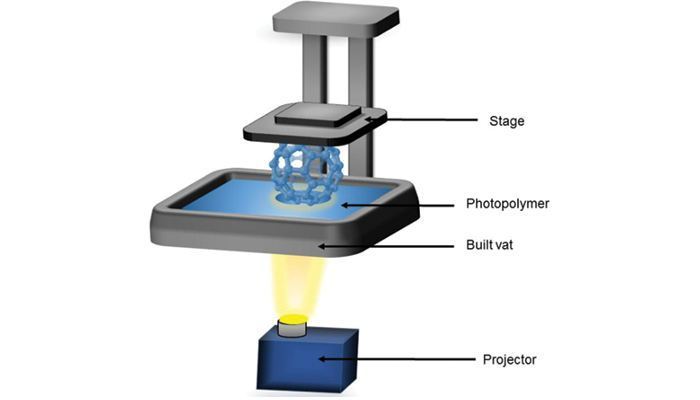

c) Washing (SLA and Photopolymerisation)

Parts that are printed with SLA or other photopolymerisation can be easily cleaned after printing. Two companies added post-processing washing machines that are seamlessly integrated in their print process line up.

Two companies added post-processing washing machines that are seamlessly integrated in their print process line up.

FormLabs added The Form Wash which uses isopropyl alcohol (IPA) to clean the parts. Carbon developed the Smart Part Washer machine to do the cleaning.

2. Fixing

Sometimes small repairs are needed to fill small holes or cracks or even to attach together parts that have been printed separately.

a) Filling

When fillers and hardeners are used to repair unwanted holes or cracks in the printed object.

b) Glueing and welding

Used when separately printed parts need to be attached together. ABS prints can be welded or glued together using acetone.

3. Curing

Just like french fries, baking the models after they have been printed enhances the mechanical properties (crunchiness in case of the fries) of the material.

Formlabs and Carbon have added curing using UV light to their printing process (SLA and CLIP respectively, both Photopolymerisation processes). After the model has been printed special curing machines heat the model to bring the part to its optimal mechanical properties. Curing therefore differs from the other post processing options, that it enhances not just the aesthetic characteristics, but the physical quality of the model.

After the model has been printed special curing machines heat the model to bring the part to its optimal mechanical properties. Curing therefore differs from the other post processing options, that it enhances not just the aesthetic characteristics, but the physical quality of the model.

4. Surface Finishing

After the washing, cleaning, removing support or excess material and curing, different processes are available to make the model look nicer aesthetically. This is especially relevant when the models are geared towards consumer markets.

a) Sanding

Layer lines or touch-points where support structure was attached to the model can be removed by carefully sanding the surface of the model, using sanding paper with varying grit: from low to high for finishing.

Aside from being labour intensive, manual sanding can create inconsistent results. With automated polishing, this can be avoided.

Layer lines are particularly visible on 3D models produced using layering techniques (like FDM).

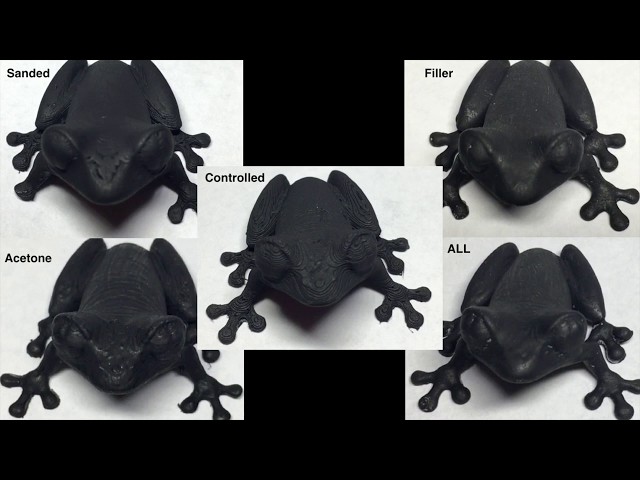

b) Vapour or Chemical Smoothing.

Sometimes chemicals are used to smoothen the model surface. The vapours react with the outer layer of the object. The layer lines are melt away, leaving a smooth outer layer while giving the model a glossy look.

For models printed with PLA and ABS the acetone is often used, or the chemical agent Tetrahydrofuran (THF).

The problem with this technique is that is cannot be controlled: small features can be melted off that should remain. Also, the vapours can be harmful when inhaled. This can be avoided using closed chemical cleaning machines.

5. Colouring

In some cases, 3D models can be printed using coloured material and with multi-material printing (multi-) coloured prints can be made. But one can also opt for colouring during the post-processing phase.

Coating and painting

Parts that need colouring would ideally be printed using white material. Before the model is painted a layer of primer is usually applied. Painting can be done manually using a brush or spray. There are machines that automate spraying of parts.

Painting can be done manually using a brush or spray. There are machines that automate spraying of parts.

Where can I go for post-processing?

So, post-processing is becoming increasingly an integral part of the 3D printing process. With special post-processing machines being developed the process is becoming automated which makes it more scalable than previously possible.

You have the option to use special post processing services, but conveniently increasingly print services are providing post-processing services to their customers, offering them a one stop shop solution.

3D printed plastic post-processing, mechanical and chemical

The most popular finishing methods for 3D printed objects are sanding, sandblasting and solvent vapor treatment.

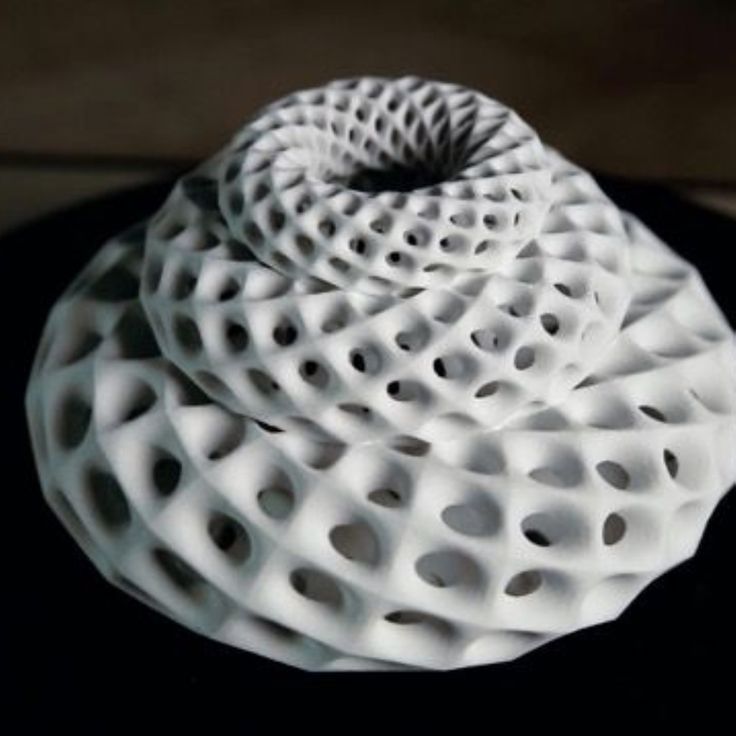

It is a misconception that 3D printing cannot produce objects that are as smooth and polished as traditional industrial technologies. Such claims can be countered with simple sandpaper, and this finishing technique is very common.

Which finishing technique is used depends largely on the geometry and material of the part. These factors determine both the level of aesthetics that can be achieved and its functionality, because different methods allow you to achieve different textures and appearances. Some methods are better suited for prototypes and exhibition models, while others are better for machine parts.

Sanding

Although fusing systems are designed to produce high-quality parts directly from the printer, layer connection lines remain visible and the end user does not need this at all, especially when it comes to a solution in which the aesthetic appearance is priority. Sanding eliminates these shortcomings and can be used for models, sales samples or concepts, fully functional prototypes and end-level assemblies and mechanisms.

Many high-quality 3D-printed objects can be smoothed with sandpaper to get rid of lines where layers overlap.

Everyone knows the process of sanding. Plastic parts are processed by hand or on a grinding machine, as is done with wooden or metal elements. Sanding is inexpensive and effective, and it is a proven method by which a quality finish can be achieved. In fact, this is the most common way to refine 3D printed objects.

Plastic parts are processed by hand or on a grinding machine, as is done with wooden or metal elements. Sanding is inexpensive and effective, and it is a proven method by which a quality finish can be achieved. In fact, this is the most common way to refine 3D printed objects.

All but the smallest details can be sanded with sandpaper. And they can be large as much as you like, although it can be difficult to manually get to small defects and irregularities. In typical situations, the process is relatively fast. In layer-by-layer welding, we are usually talking about the fight against stepped surfaces. Steps on a part the size of a remote control take about 15 minutes to clean, while painting the same part takes 2 hours due to additional steps such as preparation and drying.

When a part must be precise and durable in the first place, it is very important to consider how much material will be removed by sanding. If a lot of it is removed, it is necessary to make changes to the design before printing, to make the walls thicker. The requirements for the part also determine which sanding technique will be used, manual or mechanical, and which tool will be used.

The requirements for the part also determine which sanding technique will be used, manual or mechanical, and which tool will be used.

Sandblasting

The second most common finishing method is sandblasting. In this case, the operator controls the nozzle, from which a finely dispersed material is sprayed under pressure onto the part in order to hide traces of layers on it. The process is fast, takes 5-10 minutes, the result looks whole.

During sandblasting, a stream of small plastic particles is sent to the part placed in a closed chamber, as a result of which the surface becomes smooth after 5-10 minutes.

This technology is easily modified and can be used with most materials. It is also used during the development and manufacture of a part, at any stage - from prototyping to production. This kind of flexibility is due to the fact that processing is usually done with fine particles of finely processed thermoplastic. It is this "sand", the abrasive characteristics of which, when sprayed, are in the range from medium to high. Baking soda works very well as it is not too harsh. However, it is somewhat more difficult to work with than with plastic.

Baking soda works very well as it is not too harsh. However, it is somewhat more difficult to work with than with plastic.

One of the limitations of sandblasting is the size of the object. Since the process is carried out in a closed chamber of limited volume, it is usually up to about 60 x 80 x 80 cm.

Steaming

The third most popular finishing method is called steaming or steaming. In this case, the part is in an atmosphere of evaporation of a substance brought to the boiling point. The particles of the evaporating substance are fused into the treated surface to a depth of approximately 2 microns, making it smooth and shiny in just a few seconds. Those who prefer a matte finish can sandblast the part after steam blasting, when the part has already been smoothed and mechanical contact stress has been removed.

Acetone vapor treatment of ABS plastic makes the surface smooth and glossy, the only drawback of this technology is that corners and small parts are folded

Since the surface is very smooth, vapor treatment is widely used for consumer goods, prototypes and medical applications. The method does not significantly affect the accuracy of the part. After sandblasting, the object is ready for applying a film, protective or decorative layer. Such coatings are usually applied to more durable materials, which are subject to high requirements.

The method does not significantly affect the accuracy of the part. After sandblasting, the object is ready for applying a film, protective or decorative layer. Such coatings are usually applied to more durable materials, which are subject to high requirements.

Unfortunately, like sandblasting, steam blasting has limitations on part sizes. Unlike sanding and sandblasting, steam blasting also has material limitations. Acetone is used to process ABS plastic. When processing PLA plastic, tetrahydrofuran or dichloromethane is used. Processed materials are quite practical and durable, created products retain their original strength and flexibility.

Processing 3D printed models

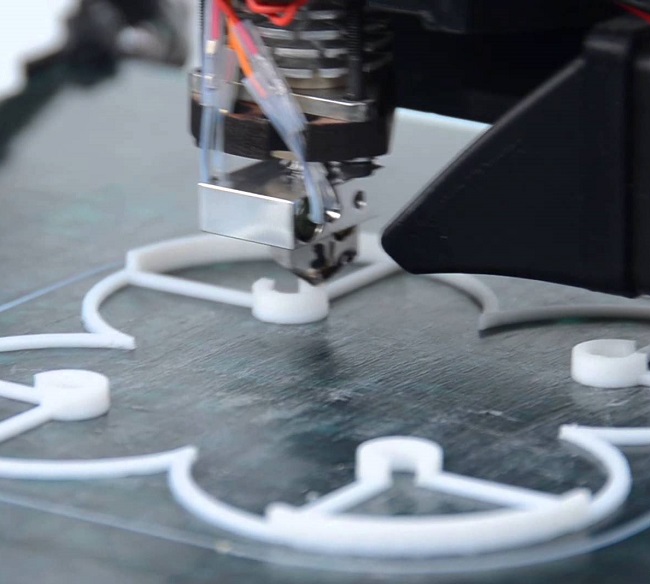

One of the problems that all fans of FDM 3D printing, without exception, encounter is the ribbing of external surfaces. Since the technology itself is based on the sequential application of layers of plastic, this effect cannot be avoided.:quality(80)/images.vogel.de/vogelonline/bdb/1488400/1488412/original.jpg) You can, of course, make it less noticeable by increasing the vertical resolution of the printer (i.e. applying thinner layers), but you won’t be able to completely get rid of the ribbing.

You can, of course, make it less noticeable by increasing the vertical resolution of the printer (i.e. applying thinner layers), but you won’t be able to completely get rid of the ribbing.

PLA 3D model before and after torch treatment. Visible internal structure under the sagging outer layer

Almost from the very first days of the RepRap project, the search began for methods of processing finished models in order to smooth surfaces. Emphasis was placed on two features of thermoplastics: the ability to melt when exposed to high temperatures and soften on contact with the appropriate chemicals.

As a rule, heat treatment does not give good results - it is quite difficult to control the heating of the surface, and this leads to plastic boiling, sagging or simply emitting toxic fumes. However, this method can be tried on solid PLA models.

Chemical treatment is more promising, but it also comes with its own set of challenges. In addition to technological problems, the problem of reagents is relevant - different plastics react with different solvents. If acetone perfectly dissolves ABS plastic, then it has almost no effect on PLA plastic. With limonene, everything is exactly the opposite.

If acetone perfectly dissolves ABS plastic, then it has almost no effect on PLA plastic. With limonene, everything is exactly the opposite.

The main chemical smoothing techniques still revolve around ABS plastic due to its high popularity and low cost of suitable solvents.

A typical ABS solvent is acetone. Its good dissolving power allows it to be used as an adhesive for component parts of ABS models, although a homemade mixture is usually used for this, produced by dissolving ABS chips in acetone. The same glue (only a thicker consistency) is often used to repair delaminations or cracks.

Along with increased aesthetics, an important factor in the development of smoothing methods is increased strength. The monolithic outer shell reinforces the models, preventing delamination and ensuring their tightness.

Hand shaping

Makeraser is a combination tool designed to also work on the outer surface of models

It is not surprising that the first thing 3D makers armed with ordinary brushes with natural bristles (synthetics can dissolve) in an attempt to smooth out their models. However, processing with a brush is a laborious task, and even requiring a certain skill. After all, already softened plastic is easy to deform with the brush itself, that is, the hairs will leave a mark on the plastic, which may not even out before the acetone evaporates. It is possible to equalize pronounced irregularities with this method, but it is quite difficult to achieve a smooth surface.

However, processing with a brush is a laborious task, and even requiring a certain skill. After all, already softened plastic is easy to deform with the brush itself, that is, the hairs will leave a mark on the plastic, which may not even out before the acetone evaporates. It is possible to equalize pronounced irregularities with this method, but it is quite difficult to achieve a smooth surface.

The advantage of this treatment is the selective application of acetone, which avoids smoothing sharp corners. After all, a pyramid was built for Cheops, not a cone, right?

An attempt to create a special tool for manual processing was a device called Makeraser. Basically, it's a simple felt-tip pen with a reservoir filled with acetone or acetone glue and a built-in scraper to remove models from the platform. From a practical point of view, this tool is best suited for gluing parts of a model or applying ABS/Acetone glue to the build bed just before printing to combat underlayer curl.

Acetone dip

Failed dip leveling attempts

A more promising and simpler method is acetone dip. Exposure of the ABS model in undiluted acetone for about 10 seconds is sufficient to dissolve the outer layer of the model. The specific exposure time may vary depending on the quality of the original model and the concentration of acetone. Since the sale of pure acetone is regulated, a technical solvent can be used.

After exposure, the model must be exposed to air until the acetone has evaporated. The process may take about half an hour.

Although this method is quite fast, it is difficult to control the process. With excessive exposure, the model will simply begin to dissolve, quickly losing small features. In addition, contamination of acetone with plastic of the same color can lead to streaks on subsequent models dipped in the same solution. A more controlled process is acetone vapor treatment.

Probably the most efficient way to get glossy ABS models. This method requires placing the model in a container with a small amount of acetone at the bottom. The model itself should not come into contact with acetone, so the model should be placed on a platform or hung above the surface of the solvent. When installing on a platform, the material properties of the stand should be taken into account. Wood is not suitable for this task due to its porosity: the bottom surface of the model will stick to the wood, and it will be quite difficult to separate it. The best option is to use a metal stand.

It is advisable not to use wood as a platform

After placing the model, the container must be heated to increase the temperature of the acetone. Acetone also evaporates at room temperature, but too slowly. Please note that boiling acetone is not recommended, as this will cause condensation to accumulate on the model, which in turn can cause streaks. Thus, for best results, do not exceed the temperature threshold of 56°C.

A safe, homemade steamer that uses boiling water in an external pot to heat the acetone in an internal one.

Holding time varies greatly with the temperature of the acetone. So, when boiling, only a few seconds can suffice, while experiments at room temperature required up to 40 minutes of exposure. Fortunately, using a transparent container, you can determine the readiness of the model "by eye".

As with dipping, the completed model must be aired out before the outer surface hardens, avoiding unnecessary physical contact.

Both when immersing models in acetone and when working with steam, the wall thickness of the models must be taken into account. The shell must be thick enough to withstand the inevitable loss of the outer layer. In addition, especially subtle features may simply dissolve, and sharp corners will be smoothed out.

Safety Instructions

Results of Successful Treatment of an ABS Model with Acetone Vapors

Acetone is not considered to be highly toxic, but care must be taken nonetheless. Inhalation of vapors can lead to pulmonary edema and pneumonia. A sign of poisoning is a feeling of intoxication, accompanied by dizziness. In addition, acetone causes irritation of the mucous membranes. When working with acetone, do not neglect personal protective equipment - goggles and gloves.

Particular attention should be paid to the flammability of acetone. Air mixtures with an acetone concentration of up to 13% by volume are explosive - when processing with acetone vapors, it is strongly recommended to work in a well-ventilated room and, if possible, use an exhaust hood. Do not use an open fire to heat acetone: since solvent vapors are heavier than air, they will displace air from the vessel, and once outside, they will cool and come into direct contact with the fire with all the ensuing consequences. It is also not recommended to tightly close the vessel, especially with strong heating, in order to avoid destruction under pressure.

Commercial versions

Stratasys Finishing Touch Smoothing Station

In addition to the Makeraser described above, there are also commercially produced units for steaming both acetone and other solvents - dichloromethane, butanone, etc.