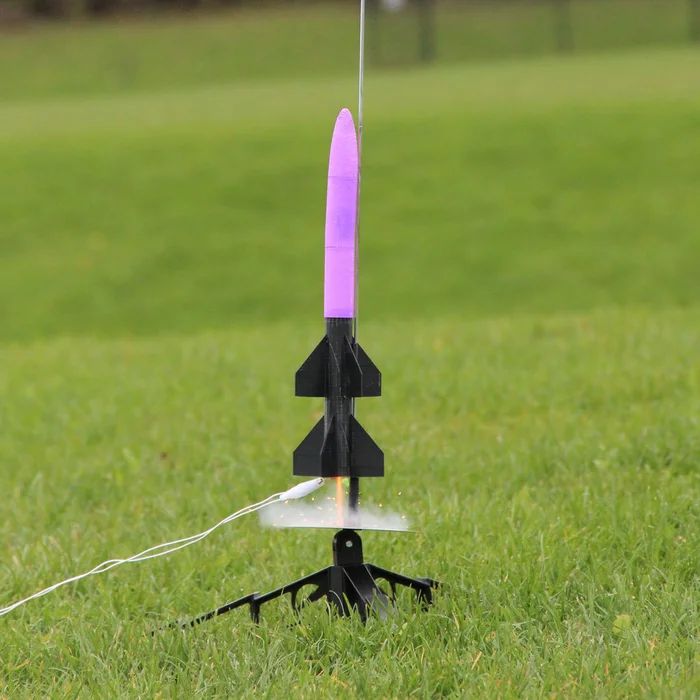

3D print rocket

3D-Printed Rockets Set To Blast Off

Relativity Space stage 1 3D-printed rocket being installed at Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Trevor Mahlmann/Relativity SpaceIf this summer's Terran1 launch from Cape Canaveral is a success, Relativity Space will be the first aerospace manufacturing company to send an entirely 3D-printed rocket into space. Soon after, a California start-up called Launcher will deploy its Orbiter satellite platform powered by 3D-printed rocket engines after getting a boost into space from a SpaceX.

It's hard to overestimate the impact 3D printing – also called additive manufacturing – has had on the space industry. No other technology has enabled so many companies to enter this industry and deliver vehicles, engines, and rockets in so short a time at such low costs. And now, the number of start-up rocket manufacturers is poised to boom as more commercially available 3D printers prove up to the task of churning out space-worthy components.

For example, UK-based aerospace company Orbex hopes its 3D-printed rockets, made with the latest metal 3D printer from German manufacturer EOS, will blast off from Scotland by the end of the year. And in the U.S., young rocket engine maker Ursa Major is taking orders now for its new Arroway propulsion engine designed to displace the now-unavailable Russian-made propulsion sources. It’s also 3D printed using available metal 3D printers.

“I don’t think our company would exist without 3D printing,” says Jake Bowles, director of advanced manufacturing and materials at Ursa Major, who spent five years at SpaceX. “Our evolution was strongly tied to the existence and the maturity of 3D printing.”

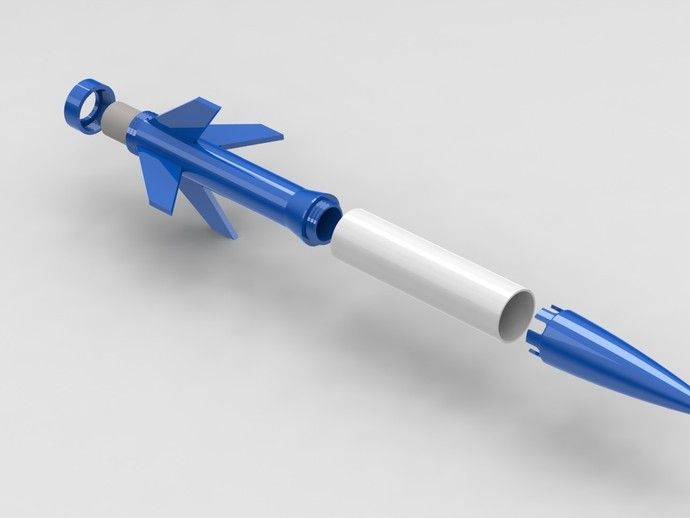

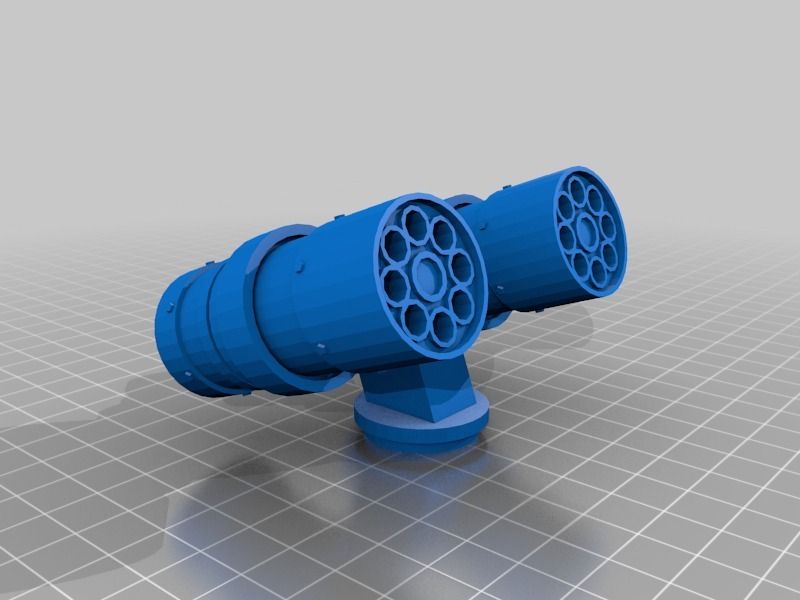

Render of Ursa Major’s 3D-printed Arroway heavy-launch engine.

Ursa MajorMORE FROMFORBES ADVISOR

Ursa Major set out to bring an engine to market at a much faster pace than it had been done before, in months not years, which was only possible by prototyping and manufacturing with 3D printers, says Bowles.

While Relativity Space and others have developed proprietary 3D printing technology for their rockets, Bowles says using new commercial 3D printers enabled Ursa Major to keep costs under control and iterate on designs rapidly, without having to stumble through the early technology development required with homegrown 3D printers.

“Our team is constantly evaluating new 3D printer companies coming out with innovations because there's a lot of competition for a share of the aerospace and space launch market,” says Bowles. The global aerospace 3D printing market size is predicted to reach $9.27 billion by 2030, according to Strategic Market Research.

Companies are racing to offer the most powerful, most flexible, and cheapest options to companies, such as AmazonAMZN , that are looking to put satellites into orbit to deliver global broadband, capture high-resolution images of activity on earth, and even establish private space station hotels for the ultra-wealthy.

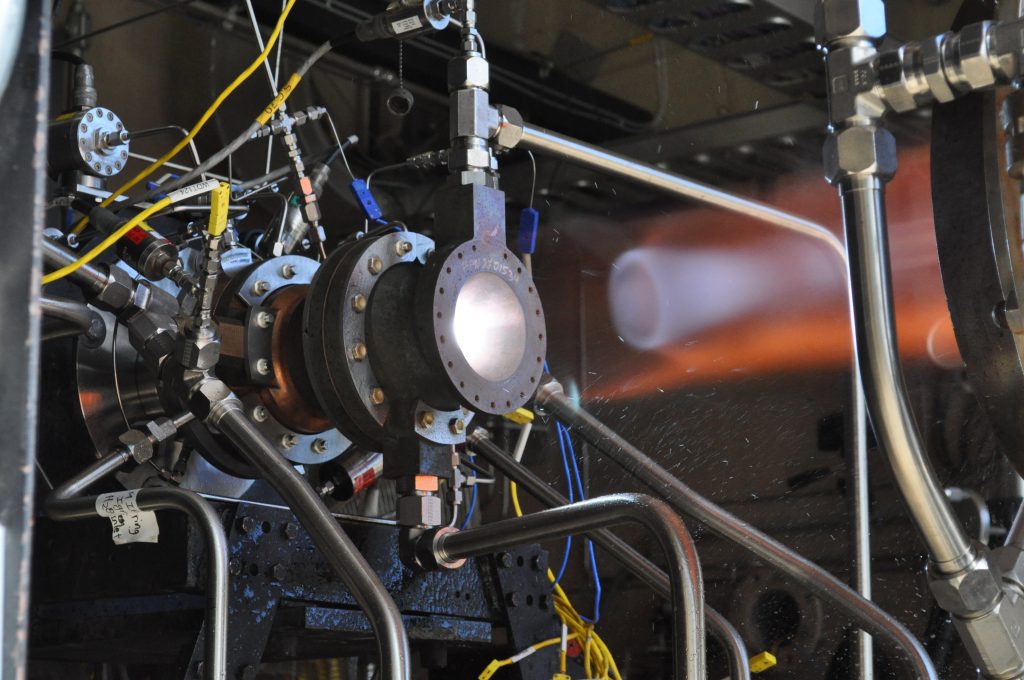

The combustion chamber of the Launcher E-2 rocket engine is fully 3D-printed in copper alloy on an ... [+] AMCM version of an EOS printer while the rocket's injector was 3D printed on a Velo3D Sapphire.

Launcher3D Printing Fueling the Race to Commercialize Space

With additive manufacturing technology cutting launch costs by as much as 95% compared to the NASA space shuttle program, the door is open for more services from orbit driving stiff competition among rocket makers. Launcher’s company slogan reads like a Walmart ad: “Anywhere in space at the lowest cost.”

Launcher’s company slogan reads like a Walmart ad: “Anywhere in space at the lowest cost.”

Chipping millions off the cost of deploying satellites recently garnered Launcher funding from the U.S. Space Force to further develop its E-2 3D-printed, high-performance liquid rocket engine for the Launcher Light launch vehicle, scheduled to fly in 2024. U.S. Space Force said: “Launcher’s E-2 liquid rocket engine has the potential to significantly reduce the price to deliver small satellites to orbit on dedicated small launch vehicles, which is a key capability and priority for the Space Force.”

To cut costs and speed production, Launcher also uses 3D printers from EOS as well as California-based Velo3D.

“Rocket engine turbopump parts typically require casting, forging, and welding,” says Max Haot, founder and CEO of Launcher. “Tooling required for these processes increases the cost of development and reduces flexibility between design iterations. The ability to 3D print our turbopump, including rotating Inconel shrouded impellers, thanks to Velo3D’s zero-degree technology, makes it possible now at a lower cost and increased innovation through iteration between each prototype. ”

”

With traditional manufacturing methods for aerospace, it’s common to hear of nine- to 12-month lead times and huge expenses in tooling to build and test, something like a pump-fed oxygen-rich staged combustion engine, says Eduardo Rondon, a senior propulsion analyst at Ursa Major, another SpaceX veteran. “Additive manufacturing allows us to put a new design on the test stand, decide to make a change, work on an alternate architecture, print it, and get it on the stand in weeks.”

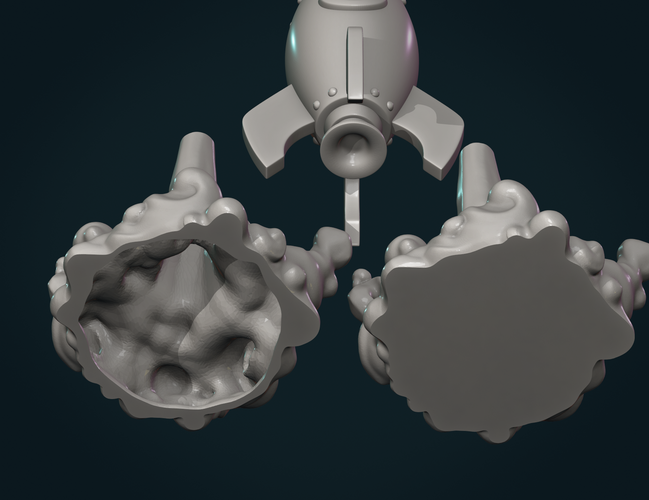

Orbex 3D prints its rockets on the same printer type as Launcher, the AMCM M4K-4 metal printing platform from EOS, which came out in 2021. The company has also used metal 3D printers from German company SLM Solutions.

In June, U.K.-based aerospace company Orbex unveiled Prime, a prototype of its 3D-printed ... [+] small-satellite launching rocket powered by seven 3D-printed engines.

Orbex3D Printing Not Just for Start-Ups

3D printing has a long history in space ever since SpaceX unveiled its 3D-printed SuperDraco rocket engine in 2013.

Aerospace giant Aerojet RocketdyneAJRD redesigned its Bantam rocket engine family in 2017 take full advantage of additive manufacturing capabilities that reduce the total design and manufacturing time from more than a year to a couple of months while lowering the cost by about 65% compared to conventional manufacturing methods.

"These engines, which would normally be composed of over 100 parts, are built from only three additive-manufactured major components: the injector assembly, the combustion chamber, and a monolithic throat and nozzle section," the company says.

Rocket Lab, another pioneer in commercial satellite launches, first launched its lightweight 3D-printed rocket engine, the Rutherford, in 2017. Its combustion chamber, injectors, pumps, and main propellant valves are all 3D-printed and have already powered 27 launches, including the one this week.

On Tuesday, Rocket Lab’s Rutherford engine powered the company’s Electron rocket from New Zealand with a NASA payload bound for the moon.

Despite the fact that NASA and seasoned launch veterans have tested, validated, and incorporated additive manufacturing into their programs for years, today’s commercial 3D printing technology and advanced metal alloy materials have matured so rapidly that companies like Launcher, Ursa Major, and Orbex can get from prototype to launch in less time for less money.

“We started from day one designing around 3D printing, and taking advantage of capabilities that it offers,” says Bowles. “This has allowed us to build internal know-how on how to optimize designs for 3D printing, which we can then apply to new engines that we need to develop and sell to meet market demand. And by already knowing how to do that we can get to market faster.”

Relativity is 3D printing rockets and raising billions. Will its technology work?

New York CNN Business —

A federal judge delivered a major blow to Jeff Bezos’ space company, Blue Origin, on Thursday by ruling in favor of NASA in a dispute over who will build the lander intended to take humans back to the moon.

Relativity Space, the rocket startup Ellis co-founded in 2015 after he left Jeff Bezos’ space company, plans to build fairly small rockets that can blast satellites into orbit cheaply and quickly. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the same business plan touted by dozens of rocket startups all over the world.

Relativity stands out in some respects. The company raised about $1.2 billion in just eight months, a level of investment frenzy enjoyed by few in the space industry outside of Elon Musk’s SpaceX. Relativity’s massive factory in Long Beach, California, teems with activity as rocket parts are hauled from one area to another, workers compete for oversubscribed desk space, and massive hangar doors conceal some of the largest 3D printers in the world at work.

That is the company’s defining trait.

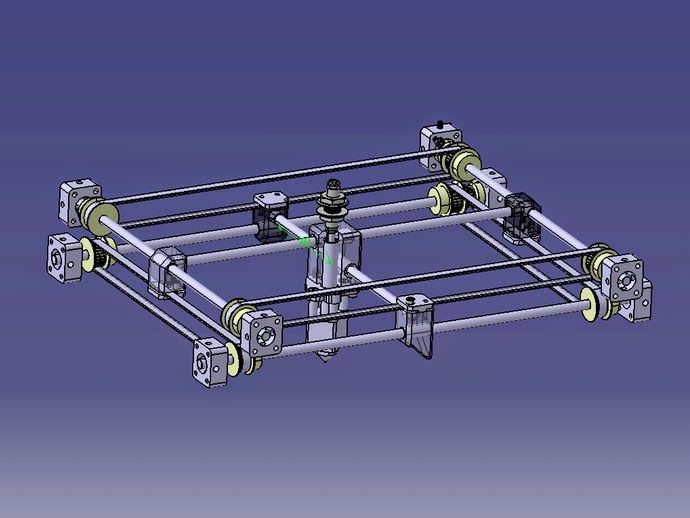

Relativity plans to 3D print almost every single component of its 200-foot-tall orbital rockets, called Terran 1. And Ellis says this is why investors are so intrigued, drawn in by the promises that Relativity’s methods will allow them to build a rocket in less than a month, while labor-driven rocket manufacturing can take months to more than a year. Using robots will also allow Relativity to quickly integrate small changes into its rockets’ design, potentially allowing the company to develop a far better product in less time, according to Ellis.

Relativity Space 3D Printer Stargate

Relativity SpaceThe catch is that Relativity has never actually launched a rocket.

And because it hasn’t launched, it’s not yet clear if 3D printing really can prove to be an effective alternative to the traditional rocket-building method, which requires tens of thousands of components. Much of a traditional rocket is also welded or assembled by hand — a process that can be both very expensive and very time-consuming.

But taking a rocket idea from the drawing board and turning it into a towering, fuel-guzzling machine that can tear away from Earth’s gravity and safely deliver a satellite into orbit is the notoriously difficult litmus test that every would-be rocket company must pass. And whether Relativity’s ideas actually translate to market efficiencies is an open question. Ellis says he understands the stakes.

And whether Relativity’s ideas actually translate to market efficiencies is an open question. Ellis says he understands the stakes.

“I think all the momentum is there,” he told CNN’s Rachel Crane. “We’ve got to show what we’ve got. But major parts of the rocket have already flown a simulated mission on the ground, and [we’re] quite confident we’ve gotten over the hump where the 3D printed rocket is now inevitable — truly inevitable.”

Relativity has backing from a who’s who of high-profile investors, such as Fidelity and BlackRock. It has soared to a $4 billion-plus valuation — one of the most valuable companies in the burgeoning commercial space sector — by attracting the type of backing most startups only dream of.

The cash windfall has given the company a gleam that belies its inexperience. The company is in the process of moving out of its current home in Long Beach into a 1.1 million-square-foot hangar where Boeing used to build C-17 cargo planes down the road. The company’s workforce has ballooned from about 100 people to roughly 600 in just a couple years. It’s hired key engineering brass away from SpaceX, Jeff Bezos’ rocket company Blue Origin and big tech firms such as Microsoft.

The fact that Relativity has drawn so much investor attention while its rockets were still essentially showroom objects is a testament to the fact that private investing markets are awash with record amounts of cash, and the moneyed are anxious to park their extra bucks where they stand to make big returns — high risk, high reward.

Ellis says investors also have good reason to be confident in his technology.

Other rocket factories use 3D printers to quickly draft up certain components, but most components are brought in from suppliers via a complex supply chain. At Relativity, the rocket parts are almost entirely constructed by one-armed robots, spewing metals into intricately designed pieces that can replace hundreds of tiny parts. About 90% of its rockets are 3D printed. Because of this, Relativity says it can use less than 1,000 parts where traditional rockets use more than 100,000.

Relativity Space Stargate

Relativity SpaceThe cornerstone of these 3D printing efforts is Stargate — a towering 3D printer that Relativity says is the largest in the world, and it prints with proprietary metal alloys. The machines can churn out an entire rocket fuselage in just a few days.

Ellis also told CNN’s Crane that he envisions his 3D printers can prove to be a game changer for manufacturing across several industries, including aircrafts, oil and gas refineries, wind turbines, and more.

He added in an interview with CNN’s Crane that he envisions that “3D printing with AI and robotics [are] how things are going to be built on another planet. ”

”

“I’m really long-term bullish,” he told Crane.

Relativity laid out a plan to get its rockets off the ground by the end of 2021. But, as is common in the space industry (see: Virgin Galactic, SpaceX, etc.), schedules don’t often hold. The debut launch of Terran 1 was pushed to 2022. Ellis said this week that it’ll be ready for launch in a “few months.”

There will be plenty of stakeholders waiting to find out whether it works. Relativity says it’s rockets are already booked to haul satellites to space years into the future (Ellis would not specify how many or the financial terms). And the company has a $1 billion deal with the US military’s Space Force, inked in August, as part of a broader slew of investments the military has made in the rocket industry. Relativity has also won several other military launch contracts.

Relativity says it’s rockets are already booked to haul satellites to space years into the future (Ellis would not specify how many or the financial terms). And the company has a $1 billion deal with the US military’s Space Force, inked in August, as part of a broader slew of investments the military has made in the rocket industry. Relativity has also won several other military launch contracts.

Relativity Space Launch Pad Cape Canaveral

Relativity SpaceRelativity has the funds to keep trying if it fails out of the gate, but time is of the essence. Several competitors in the small-launch vehicle arena — namely, Rocket Lab, Virgin Orbit and Astra — have already successfully gotten their vehicles off the ground.

Ellis said 95% of the Relativity team is currently focused on ensuring that its first Terran 1 mission is a success. But it’s not the company’s sole focus. It’s already planning to build a far larger rocket, called Terran R, that it hopes to launch by 2024. And recent files released by NASA show the company bid for the chance to develop a space station in low-Earth orbit. (Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, and Nanoracks were eventually awarded contracts.)

But it’s not the company’s sole focus. It’s already planning to build a far larger rocket, called Terran R, that it hopes to launch by 2024. And recent files released by NASA show the company bid for the chance to develop a space station in low-Earth orbit. (Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, and Nanoracks were eventually awarded contracts.)

Ellis, for the record, said the company is already selling rides for satellites aboard Terran R, though the rocket itself is currently little more than a digitally rendered idea.

Space is proverbially “hot right now” and standing out from the crowd, as in proving what sets a company apart from the rest is an actual game changer, will be essential.

Relativity’s approach to 3D printing has certainly given it cache. The company has proven itself in the private fundraising markets, giving it the leeway to forgo a rushed stock market debut that so many of its competitors have embraced.

But as with most things in the aerospace industry, it can be difficult to discern the hype and bluster from the truly transformative. And in that case, Relativity’s true proving ground will be on the launch pad.

“We have a lot to deliver and a lot of value we’ve signed up to create,” Ellis told CNN Business. “I’m super humbled by it. Like, these people are lining up for Relativity, and other rocket companies can’t say that.”

“I’m super humbled by it. Like, these people are lining up for Relativity, and other rocket companies can’t say that.”

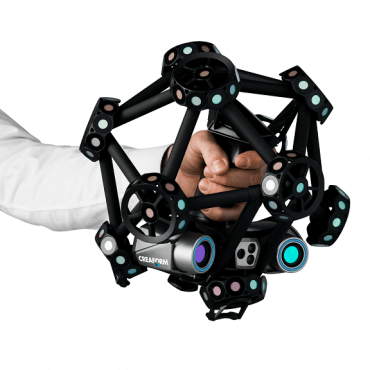

How Relativity Space prints rockets on a 3D printer

Relativity Space co-founder, CEO Tim Ellis / Relativity Space / AFP

Relativity Space is printing a metal space rocket on a 3D printer that it invented specifically for this purpose. Almost all: 95% is printed, and the remaining 5% falls on electronics, seals and some other elements. 3D printing has many advantages. She's cheaper. She's faster. It is made on the spot, no need to wait until the parts are brought from another factory. It is stronger: fewer places for fastening parts. “The Shuttle had 2.5 million parts,” says Relativity Space co-founder Tim Ellis. “According to our estimates, SpaceX and Blue Origin have reduced this number to 100,000 per rocket. We have a thousand - less than in your car.

Many space companies use 3D printing, but only for individual components. Skeptics insist that no one knows how the printed rocket will behave during takeoff and in space. So far, the startup's first rocket, Terran 1, has successfully passed all ground tests. The first copy for a real flight is collected slowly and carefully checked. Now it is ready for 85%. A test flight is scheduled for the end of this year. But investors believe in the idea. Last November, Relativity Space completed a series funding round and raised $500 million. After that, according to research company Pitchbook, with a business valuation of $2.3 billion, Relativity Space became the second most valuable venture capital-funded space company in the world. In 1st place, of course, SpaceX (however, Pitchbook does not include Blue Origin in the rating, which is fully funded by Jeff Bezos).

So far, the startup's first rocket, Terran 1, has successfully passed all ground tests. The first copy for a real flight is collected slowly and carefully checked. Now it is ready for 85%. A test flight is scheduled for the end of this year. But investors believe in the idea. Last November, Relativity Space completed a series funding round and raised $500 million. After that, according to research company Pitchbook, with a business valuation of $2.3 billion, Relativity Space became the second most valuable venture capital-funded space company in the world. In 1st place, of course, SpaceX (however, Pitchbook does not include Blue Origin in the rating, which is fully funded by Jeff Bezos).

Relativity Space has since raised another round, raising $650 million, based on a company-wide valuation of $4.2 billion. reusable. After all, competitors do not sleep. Relativity Space is just one of more than a dozen rocket companies created in the last 10 years.

Launch from Mojave

Ellis was born in 1990 in Texas. He is the eldest of three children of an architect father and a dentist mother. As a child, Ellis was fond of Lego and persuaded his parents to buy about 200 sets. He immediately threw away the instructions from them and collected the spaceships he invented himself. Until now, the thumb of his right hand, when at rest, arched back more than his left - Ellis assured the Los Angeles Times that this was the result of long hours when he assembled and disassembled the parts of the designer.

He is the eldest of three children of an architect father and a dentist mother. As a child, Ellis was fond of Lego and persuaded his parents to buy about 200 sets. He immediately threw away the instructions from them and collected the spaceships he invented himself. Until now, the thumb of his right hand, when at rest, arched back more than his left - Ellis assured the Los Angeles Times that this was the result of long hours when he assembled and disassembled the parts of the designer.

As Ellis got older, he began making amateur films with his friends, mostly action movies, where the characters were often confronted by zombies. He entered the University of Southern California to become a screenwriter. But already in his first year, he became interested in the profession of an aerospace engineer and joined the Rocket Propulsion Lab at the university, which was engaged in the development of rockets.

The University of Southern California is known for its space program. Its alumni include Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong, astronaut and former head of NASA Charles Bolden, and Dana Rohrabaker, chairman of the House Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee. There are several laboratories where students create real rockets and satellites. “I was amazed,” Ellis recalled in an interview with the university website about the first time he went to test the rocket engine he designed and built with his comrades in the Mojave Desert. – I always advise students: take part in practical classes. So you will understand why you need to study this or that differential equation, scheme or line of code.

There are several laboratories where students create real rockets and satellites. “I was amazed,” Ellis recalled in an interview with the university website about the first time he went to test the rocket engine he designed and built with his comrades in the Mojave Desert. – I always advise students: take part in practical classes. So you will understand why you need to study this or that differential equation, scheme or line of code.

They wanted to be the first student group to launch a rocket into space. But, having carried out dozens of successful launches, they did not even achieve a suborbital flight - this was done by their successors in 2019, having developed more powerful engines.

Why leave Bezos and Musk

At Rocket Propulsion Lab, Ellis met and became friends with classmate Jordan Noone. Then their paths diverged for a while. Noon went to SpaceX, where he worked, among other things, on the Dragon 2 spacecraft. His emergency rescue system uses a 3D printed SuperDraco engine.

Ellis interned for three summers at Bezos' Blue Origin, and after graduation he was accepted full-time. He convinced Bezos to create a metal 3D printing division (by then many competitors, including Boeing, were doing it). He also created it from scratch. The traditional way of producing parts is turning on a lathe, stamping or casting with a mold. In 3D printing, robotic arms deposit layer upon layer of molten metal. A printed rocket has fewer parts, and therefore, places to connect them using welding, rivets, etc., and therefore fewer vulnerabilities. Skeptics object that if defects are found, the entire part has to be discarded and its manufacture must be started anew. But Ellis says that Relativity Space has developed a way to restart the printing process from the right place. “3D printed rockets are the future of rocketry and space exploration,” he told Inc. magazine.

Ellis and Noon often called each other and talked about rockets, although they worked for different space companies. They put together a rough cost structure to understand why rockets are so expensive. “80 to 90% goes to wages,” Noon told Bloomberg. 3D printing can dramatically reduce these costs.

They put together a rough cost structure to understand why rockets are so expensive. “80 to 90% goes to wages,” Noon told Bloomberg. 3D printing can dramatically reduce these costs.

Ellis once mentioned that he was going to start a startup to 3D print entire rockets. He later admitted to Inc. that he tried to get Bezos to print more parts for the rocket, but his suggestions were never fully implemented. Then he decided to take up rocket science himself. Noon liked the idea. Both left in December 2015 to create startup Relativity Space.

“I never saw him give up, give up, or fail to solve a problem, even a really difficult one,” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times of Noon. “I knew our startup was going to have a lot of problems, and he was the right person to make it all work.” And Noon noted: “I am strong in technical and practical aspects, and Ellis is strong in creative thinking and non-standard solutions.”

For 1 kg of satellite

Relativity Space received its first money from venture investor Mark Cuban. Ellis and Noon made about 20 attempts to guess Cuban's email address, as Cuban preferred texting to other forms of communication. Some of the letters were returned with a note that such an address does not exist, some got to other people. But one of the addresses turned out to be correct, and Cuban read the letter with the headline "Space Is Sexy: 3D Printing of an Entire Rocket." Ellis and Noon asked for $100,000. Cuban, after five minutes of texting them, agreed to invest $500,000 (although they had to wait two months to check if they were fraudsters). “They are smart, resourceful, driven and always learning,” Cuban wrote in an email to The Times. “These are exactly the traits I look for in innovators.”

Ellis and Noon made about 20 attempts to guess Cuban's email address, as Cuban preferred texting to other forms of communication. Some of the letters were returned with a note that such an address does not exist, some got to other people. But one of the addresses turned out to be correct, and Cuban read the letter with the headline "Space Is Sexy: 3D Printing of an Entire Rocket." Ellis and Noon asked for $100,000. Cuban, after five minutes of texting them, agreed to invest $500,000 (although they had to wait two months to check if they were fraudsters). “They are smart, resourceful, driven and always learning,” Cuban wrote in an email to The Times. “These are exactly the traits I look for in innovators.”

First, the startup needed to create a huge 3D printer - there were no models on the market suitable for their purposes. A lot of effort was put into this. But now the latest generation printer is able to print a part up to 32 feet (almost 10 m) high, while the height of the Terran 1 rocket is 115 feet (35 m). Ellis and Noon say that even if the rocket venture fails, they can always cash in on the sale of industrial 3D printers.

Ellis and Noon say that even if the rocket venture fails, they can always cash in on the sale of industrial 3D printers.

Terran 1 /Relativity Space

Created with Cuban's money, the first printer could print parts half the size of the last generation. But the working rocket engine printed on it made an impression on investors. First, they invested almost $10 million in the startup, then another $35 million, and in October 2019d. - another $ 140 million. Ellis and Noon planned to stop there. They did not want to dilute their share, and the funds raised should have been enough for the time before the first commercial launch, if they worked without haste. But in November 2020, another $500 million round of funding was raised. As Ellis explained to CNBC, “the development and scaling of the project needs to be accelerated.” That summer, the startup moved to a new 11,000-square-meter headquarters in Long Beach, California. m, where there will be a site for the production of rockets (the most important thing is that their new printer climbed there in height). Over the past year and a half, the company has more than doubled the number of employees. She now has 400+ people and plans to hire 200 more this year.

Over the past year and a half, the company has more than doubled the number of employees. She now has 400+ people and plans to hire 200 more this year.

Ellis told Inc. that they already have $1 billion in launch contracts from government and commercial entities. Terran 1 can carry up to 1250 kg of payload. This is smaller than SpaceX's Falcon 9, but larger than Rocket Lab's Electron. Relativity Space is targeting a mid-sized satellite niche, much like a car, Ellis said. Its competitors are the Russian Soyuz-2-1V and the European Vega. Or the same Electron, if Terran 1 displays several small satellites at once.

The launch cost of Terran 1 is $12 million, i.e. slightly less than $10,000 per 1 kg. Last year, Roscosmos CEO Dmitry Rogozin announced a more than 30% reduction in the price of launch services for a number of satellites to the level of SpaceX: to $15,000–17,000 per 1 kg instead of $20,000–30,000.

Target Mars

The competitive advantage of Relativity Space is not only in cost, but also in the fact that it can print a rocket to customer requirements, changing both the diameter of the rocket and the shape of the fairing for the satellite - of course, within the limits allowed by aerodynamics, Forbes explained. And she can do it quickly. Once the technology has been proven in practice, Relativity Space is going to print the rocket in 30 days and take another 30 days for pre-launch tests, Ellis told Scientific American. According to him, even SpaceX takes 12 to 18 months to build a conventional rocket. But Musk claims that his reusable rocket is ready for a new flight 51 days after the previous launch.

And she can do it quickly. Once the technology has been proven in practice, Relativity Space is going to print the rocket in 30 days and take another 30 days for pre-launch tests, Ellis told Scientific American. According to him, even SpaceX takes 12 to 18 months to build a conventional rocket. But Musk claims that his reusable rocket is ready for a new flight 51 days after the previous launch.

So in June, Relativity Space raised another $650 million from investors to accelerate the development of its own reusable Terran R rocket (of course, also almost completely printed on a printer). Its first launch is scheduled for 2024. It will be larger than the first one - 216 feet (66 m) high and designed for 20 tons of payload.

For Ellis and Noon, the main thing is that this project is another step towards interplanetary flights. Musk is looking for a way to get colonists to Mars, and Ellis and Noon are hoping to help them settle on the Red Planet. "If you believe - and I believe - that Elon [Musk] and NASA will send people to Mars, then <. ..> they will need a whole bunch of things," Ellis told CNBC. “Our printers are reducing the amount of infrastructure that would need to be transported from Earth to Mars in order to establish a colony there,” explained Noon Inc. – Traditionally, you need to send tons of equipment for a factory that will be able to produce factories that, in turn, will produce cars, houses, warehouses ... In our vision of the future, you simply send a 3D printer to Mars that prints everything using Martian raw materials this is". In a speech to the students of his alma mater, Ellis added: “We are going to 3D print the first rocket made in Mars <...> I don’t see a future in 50 years in which rockets will not be 3D printed. It just doesn't make sense otherwise, because printing is much easier and cheaper."

..> they will need a whole bunch of things," Ellis told CNBC. “Our printers are reducing the amount of infrastructure that would need to be transported from Earth to Mars in order to establish a colony there,” explained Noon Inc. – Traditionally, you need to send tons of equipment for a factory that will be able to produce factories that, in turn, will produce cars, houses, warehouses ... In our vision of the future, you simply send a 3D printer to Mars that prints everything using Martian raw materials this is". In a speech to the students of his alma mater, Ellis added: “We are going to 3D print the first rocket made in Mars <...> I don’t see a future in 50 years in which rockets will not be 3D printed. It just doesn't make sense otherwise, because printing is much easier and cheaper."

Media news2

Do you want to hide ads? Subscribe and read without distractionRelativity Space tests 3D printed launch vehicle

News

-printed components in the current iteration is already 85% and according to the developers' plans it will reach 95%.

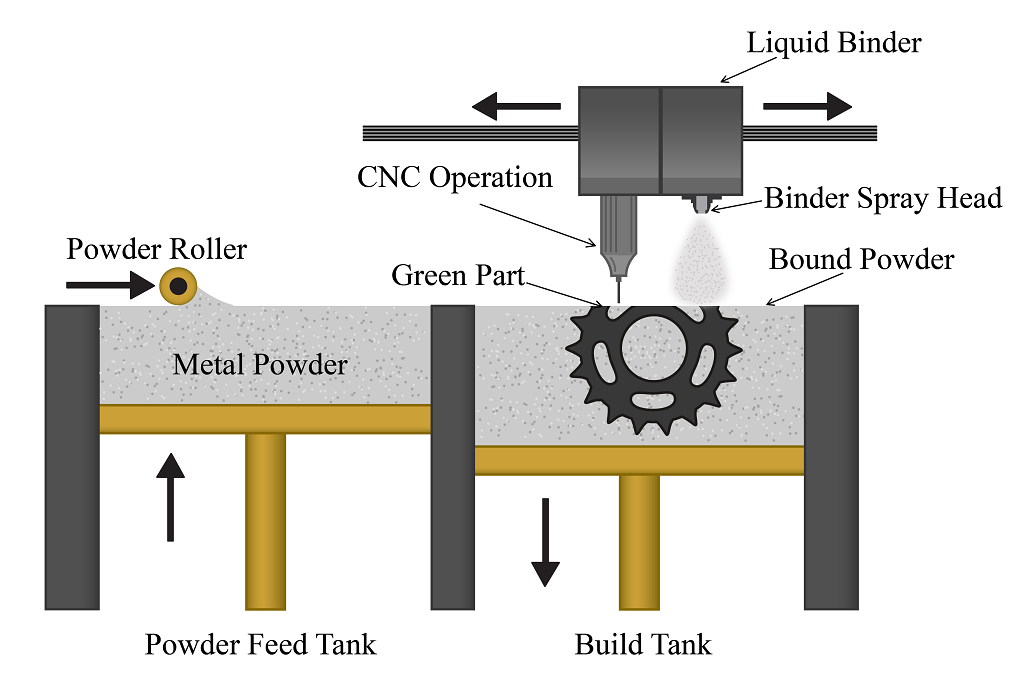

During testing, nine first stage engines ran for twenty seconds ( see video ). The Aeon 1 power plants are 3D printed and run on methane and oxygen. The company uses various 3D printing technologies, including selective laser sintering of metal powders on 3D printers manufactured by the German company EOS and laser-plasma deposition of aluminum alloys in the form of welding wire on an additive system of its own design called Stargate.

Terran launch vehicles will be able to launch up to 1250 kg of payload into low Earth orbit or up to 900 kg into sun-synchronous orbit. The first flight will take place this year, although the exact date is still unknown: the company planned to launch in June, but the schedule has shifted to the right.

The first non-commercial launch will take place from Cape Canaveral, from Launch Complex 16, leased from the US Air Force and previously used to test Titan ICBMs and Pershing short-range ballistic missiles.

In the long term, Relativity Space expects to reduce production time to two months through automation and the widespread use of additive technologies. The cost of a single launch of Terran 1 is estimated at twelve million dollars. By 2024, it is planned to complete work on a heavier Terran R launch vehicle with a payload capacity of up to twenty tons. Read more about production at the facilities of Relativity Space in the material at this link.

Space Relativity Space Terran 1

Follow author

Follow

Don't want

4

Article comments

More interesting articles

four

Subscribe to the author

Subscribe

Don't want

Establishment of the center will help improve the quality and reduce the cost of engineering products.