Legal implications of 3d printing

What Are the Legal Issues in 3D Printing?

3D Insider is ad supported and earns money from clicks, commissions from sales, and other ways.

This article is not legal advice. Do not rely upon it to be accurate. It’s for informational purposes only and you should consult with your own attorney for advice.

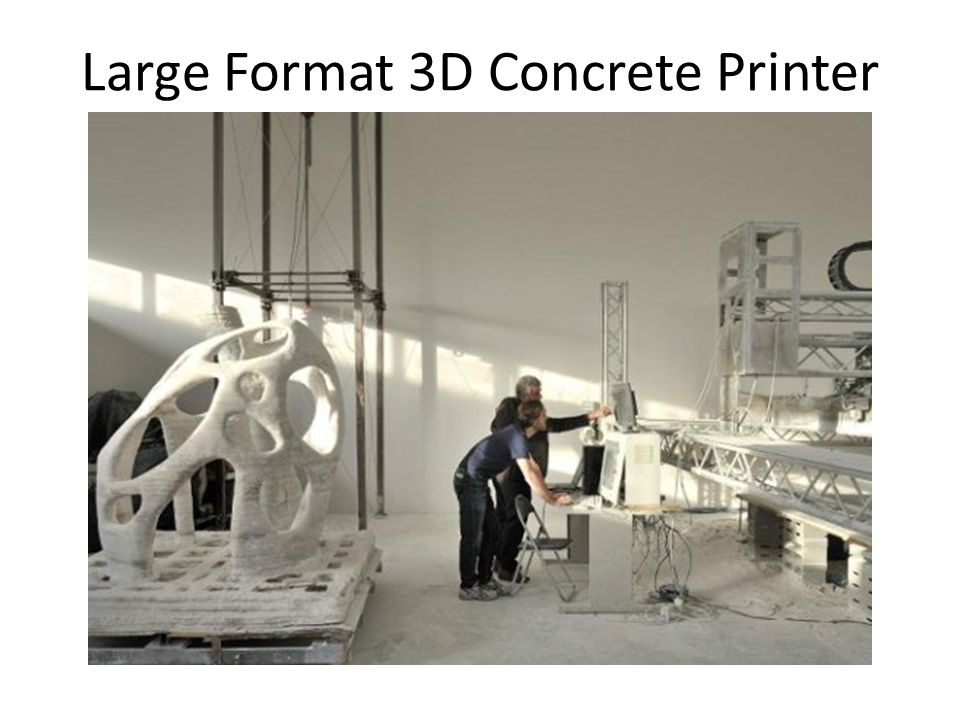

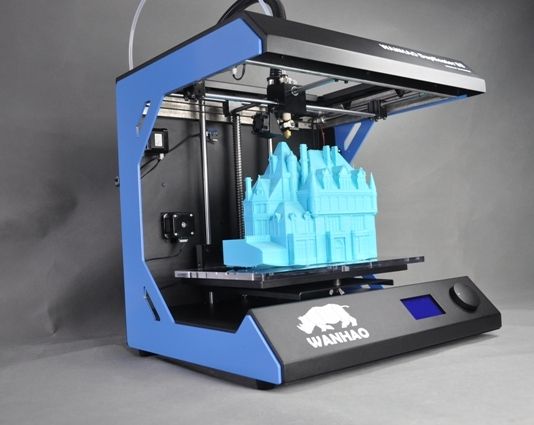

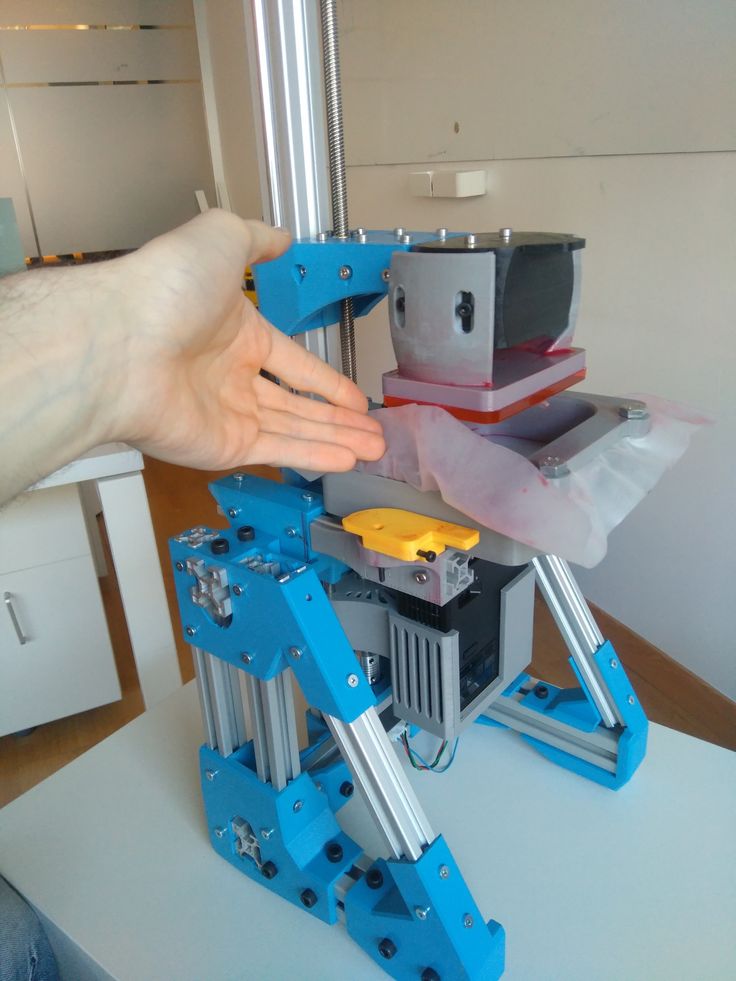

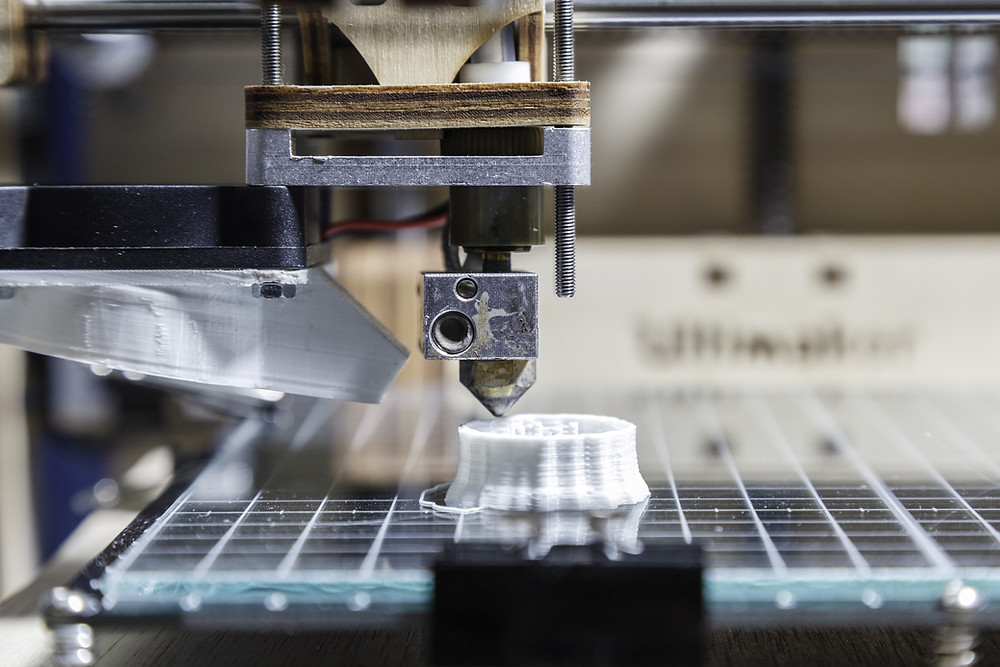

We know by now that 3D printing has become a disruptive force in the manufacturing technology. While the economics of 3D printing have not quite caught up to more traditional manufacturing processes, the design freedom that it provides and its reliance on purely digital models has made it easier to turn more creative ideas into reality.

However, the “democratization” of 3D printing technology has also brought forth several issues. Can anyone just use a 3D model downloaded from the Internet and print a product that they want to sell? Who is responsible for any accidents caused by a 3D printed product? To answer these questions, let’s look at the current and future legal issues that concern 3D printing.

Intellectual property rights

The number one legal problem that many in the field of intellectual property are concerned with is that 3D printing may provide a new avenue for piracy. After all, anyone with a 3D printer can just download 3D model off the internet to create the same product with the exact dimensions. With the proliferation of 3D scanners, it has even become incredibly easy to reverse-engineer a physical object into a digital model.

In such a situation, the ability to distribute and reproduce such models will depend on what the model was based on. There are three possible conditions to consider:

• The model is based on an item protected by intellectual property

If a model was created based on an object with a design patent, then the model itself will be subject to copyright laws as it is considered a digital copy of the object. However, it is still unclear whether patent protection extends to the actual 3D models of a product – not those that were created by 3D scanning.

This ambiguity stems from the fact that most patent laws apply only to the product or any of its copies. This is because the 3D model is not considered a product. This has proven to be quite problematic in an era where reproducing a product can be as simple as downloading a 3D model of it.

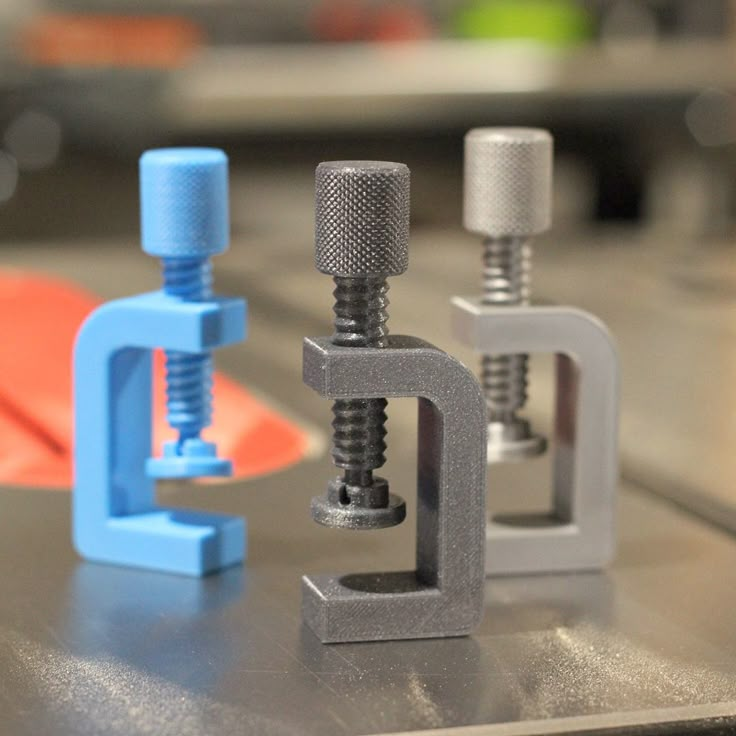

• The model was generated from a real-world object with no IP protection

With 3D scanners, anyone can scan a physical object to create an equivalent model. While some commercial products may be protected by patents, more generic ones have no protection at all. This can include generic knives, tools, or even standard household furniture.

When a person creates a 3D model from scanning, the lack of patent protection on the physical object means that the model also has no protection. This allows anyone to download the model and use it for 3D printing for any purpose they see fit.

An argument could be made that the original scanner may have made modifications to make the model compatible with 3D printers, but this isn’t likely to hold any water in a conversation about copyright.

• The model is considered a creative work

A 3D model created completely by a modeler out of nothing is considered a work of art and a product of the artist’s imagination. This makes the model eligible to have copyright protection as a piece of art or design. In such case, the artist holds copyright over the model and can determine if they will allow the model to be distributed, modified, or reused.

All this talk about intellectual property protection for 3D models fails to consider an important factor – implementation. With 3D printers becoming incredibly common and 3D models being widely distributed online, how can brands expect to keep up with possible IP violations?

For instance, it has become a common practice for people to 3D print replacement parts for their furniture or appliances. Obviously, this practice cuts on the profits of manufacturers who could have sold these replacement parts otherwise. However, companies will also need to spend money to go after individual consumers or even small corporations in an effort to protect their IP rights.

In some instances, the enforcement of IP rights will end up becoming an expensive venture company. In the end, and even with the law on their side, it can still be a losing battle. After all, it’s just about impossible to stomp out a design that has already been distributed online.

Product liability

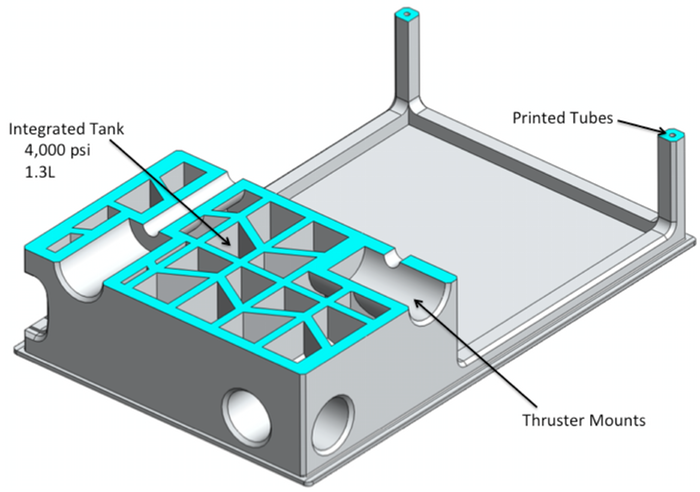

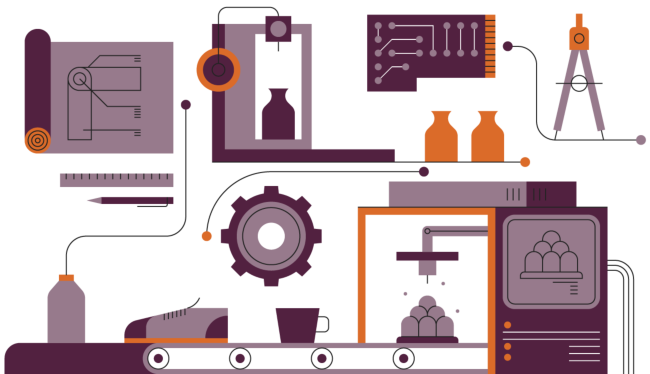

Before 3D printing, the supply chain process was pretty simple. One company designs and manufactures a product, another company might come in to take care of logistics and distribution, and the product is bought by a consumer. Should something go wrong with the product, the chain of accountability is easy to follow.

Nowadays, there are potentially so many different entities that a product design can go through before it reaches the buyer. Any person can download a 3D model, outsource the 3D printing to another company, and sell the products online. Further complicating the matter, the 3D model might even have been generated from another product.

If the final 3D printed product fails, which part of the supply chain process should be held liable? In this scenario, the number of parties involved in the process has grown a lot longer:

- The manufacturer of the original product

- The person who made the 3D model

- The owner of the 3D printer

- The manufacturer of the 3D printer

- The manufacturer of the filament

- The person who downloaded the model and outsourced the 3D printing

- Or is the buyer the one to blame?

Unfortunately, there isn’t a clear-cut answer to this question yet. It isn’t even clear if the concept of product liability applies to 3D models. After all, intellectual property has already defined the distinction between 3D models and physical products. Once a 3D model has been available online, is the original creator of the model automatically absolved of any liability?

It isn’t even clear if the concept of product liability applies to 3D models. After all, intellectual property has already defined the distinction between 3D models and physical products. Once a 3D model has been available online, is the original creator of the model automatically absolved of any liability?

If such a matter were brought to the court, the outcome may depend on a multitude of other circumstances. There haven’t been any high-profile examples of such a conflict happening, so we really have no precedence for how a court would rule. What cannot be denied is how much 3D printing technology has complicated the field of product liability.

The use of 3D printing in the medical field

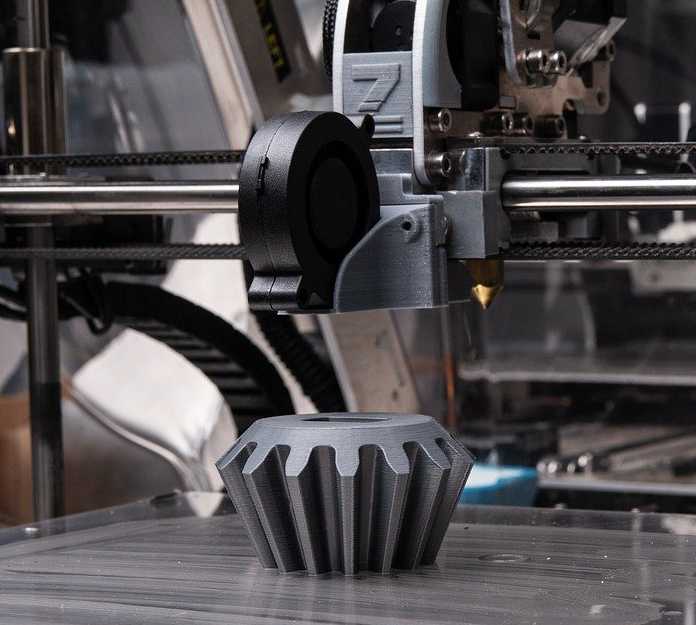

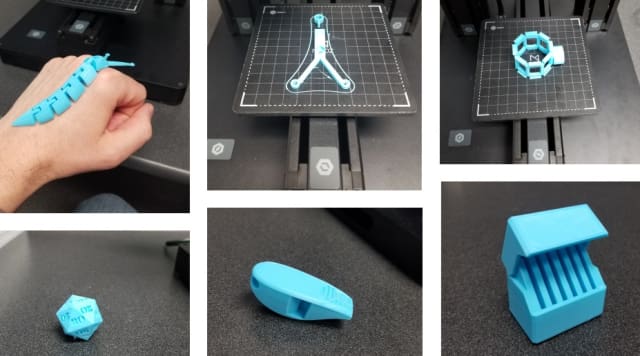

The medical field has proven to be one of the most prolific users of 3D printing, often touting how much it has revolutionized the design and manufacture of customized prosthetics and implants. By incorporating 3D scanning of actual body parts with 3D modeling, splints and prosthetics can be made to be highly anatomically accurate.

Safety, of course, is an important factor for medical 3D printing. 3D printed prosthetics need to be made using the proper material and the proper techniques, to make them biologically compatible and stable enough to withstand sustained contact with human fluids.

Thankfully, the FDA has been able to keep pace with this development and has created regulations for 3D printed medical devices. In 2016, the FDA made a landmark approval of the first 3D-printed drug, a tablet made of multiple layers of powdered medication designed for near-instant disintegration in water.

The practice of 3D printing organs and other body parts has also introduced another issue – that of data privacy and ownership. When a hospital creates a 3D model of a patient’s body part, do they retain ownership of that model? Do hospitals have the right to use and distribute these models for further research or collaboration? Does patient confidentiality also extend to 3D models?

Final thoughts

As you may have noticed, this article raises more questions than answers. That’s the nature of 3D printing as it stands right now – rapidly evolving and creating a lot of uncertainties. 3D printing is yet to achieve its full potential but has already changed the way things are done in the fields of product design, prototyping, personalized products, and, in some cases, large-scale manufacturing.

That’s the nature of 3D printing as it stands right now – rapidly evolving and creating a lot of uncertainties. 3D printing is yet to achieve its full potential but has already changed the way things are done in the fields of product design, prototyping, personalized products, and, in some cases, large-scale manufacturing.

With all the changes that 3D printing can herald, it has also brought forth legal issues that did not exist before. The copyright protection of digital 3D models is just the peak of the iceberg. Matters in data privacy and product liability are even more complex.

As 3D printing slowly becomes a mainstay in both industrial settings and home workshops, corporations and federal agencies may be forced to undergo a drastic paradigm shift. Never before has a manufacturing process been so accessible to the common people. This evolution will have to take place in all fronts – technology, business, commerce, and legislation.

Warning; 3D printers should never be left unattended. They can pose a firesafety hazard.

They can pose a firesafety hazard.

3D printing and IP law

February 2017

By Elsa Malaty, Lawyer, Associate in the law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP, and Guilda Rostama, Doctor in Private Law, Paris, France

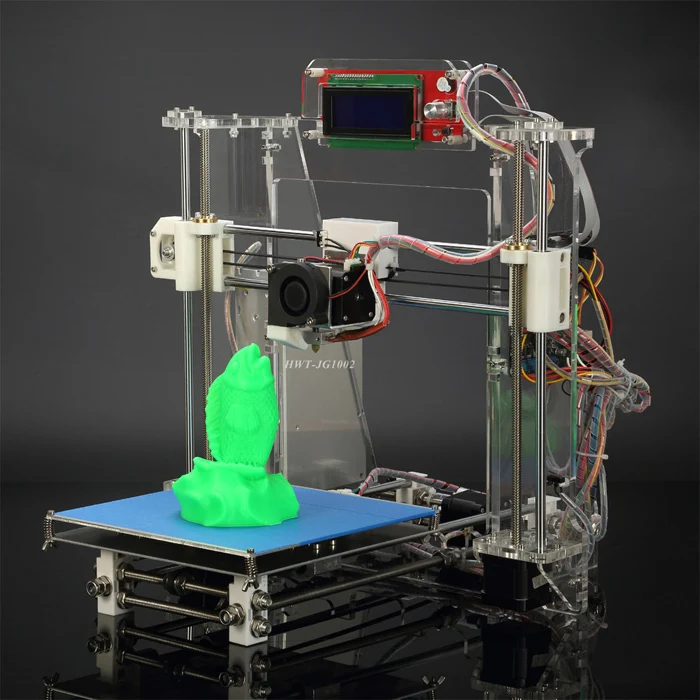

3D printing technology emerged in the 1980s largely for industrial application. However, the expiry of patent rights over m�any of these early technologies has prompted renewed interest in its potential to transform manufacturing supply chains. The availability of low-cost, high-performance 3D printers has put the technology within reach of consumers, fueling huge expectations about what it can achieve. But what are the implications of the expanding use of this rapidly evolving and potentially transformative technology for intellectual property (IP)?

Using a commercially available 3D printer, researchers at the National University of Singapore have found a way to print customizable tablets that combine multiple drugs in a single tablet so doses are perfectly adapted to each patient. (Photo: Courtesy of the National University of Singapore).3D printing in a nutshell

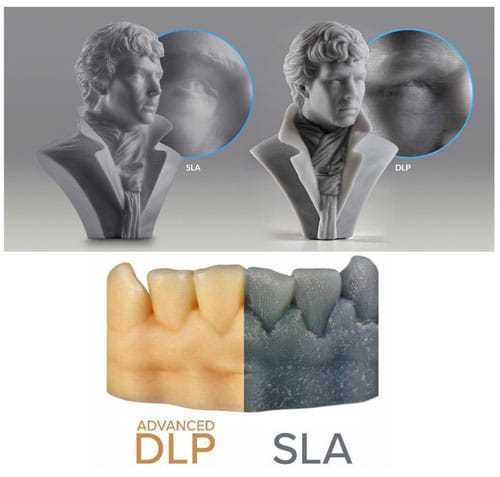

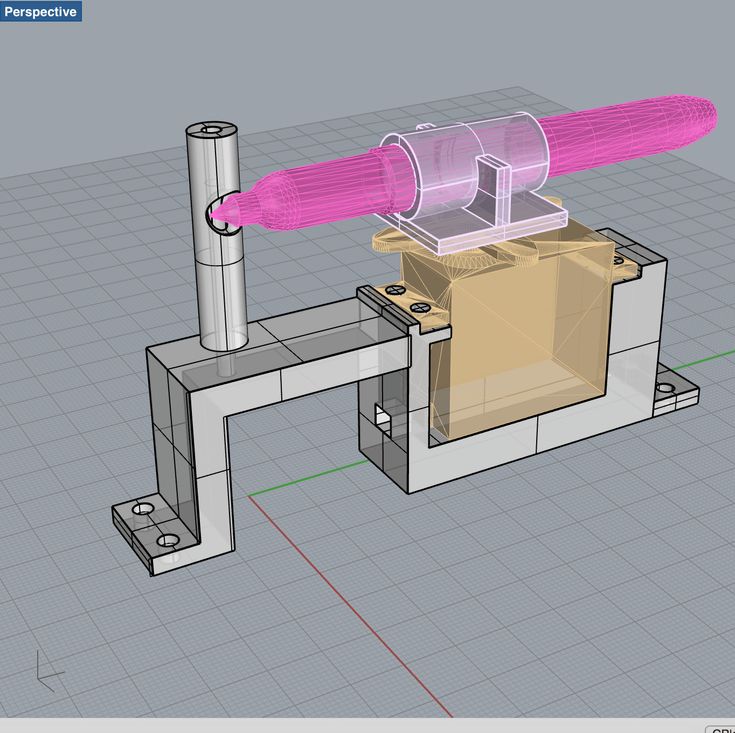

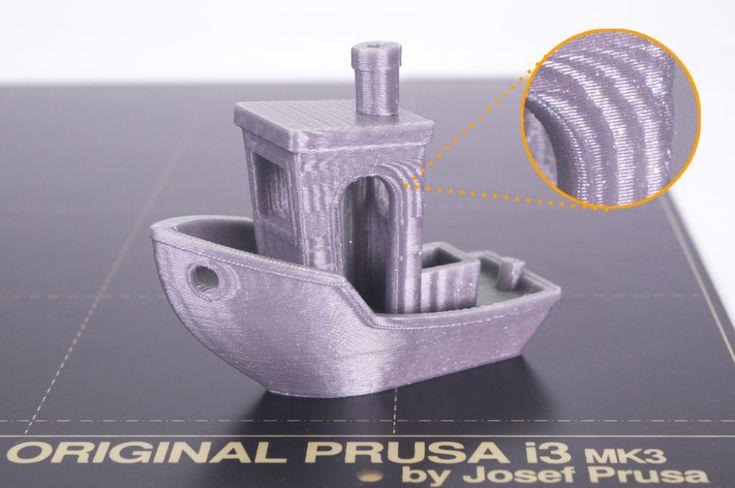

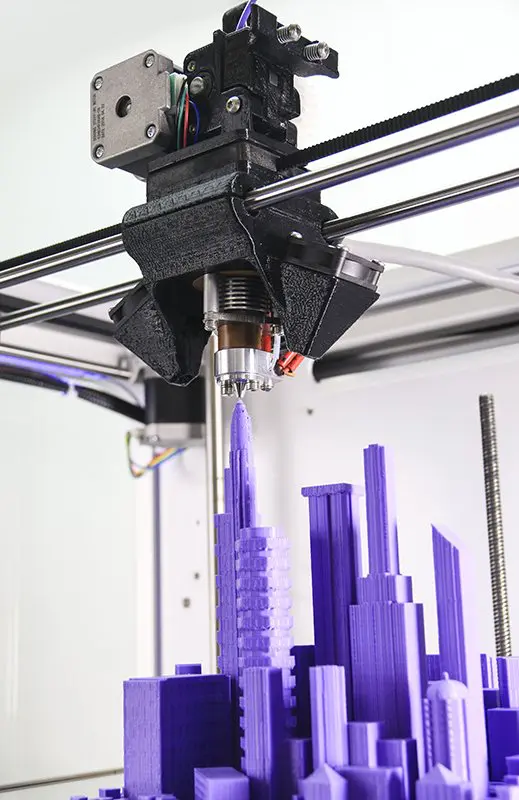

(Photo: Courtesy of the National University of Singapore).3D printing in a nutshellThe 3D printing process starts either with a digital file in which the object to be printed is digitally formatted using either 3D print software, or a 3D scanner. The file is then exported to a 3D printer using dedicated software, which transforms the digital model into a physical object through a process in which molten material is built up layer upon layer until the finished object emerges. This process is also referred to as additive manufacturing.

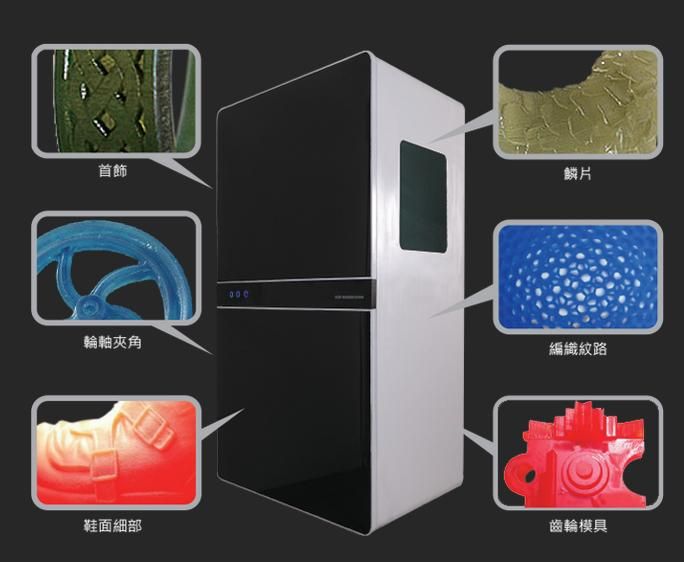

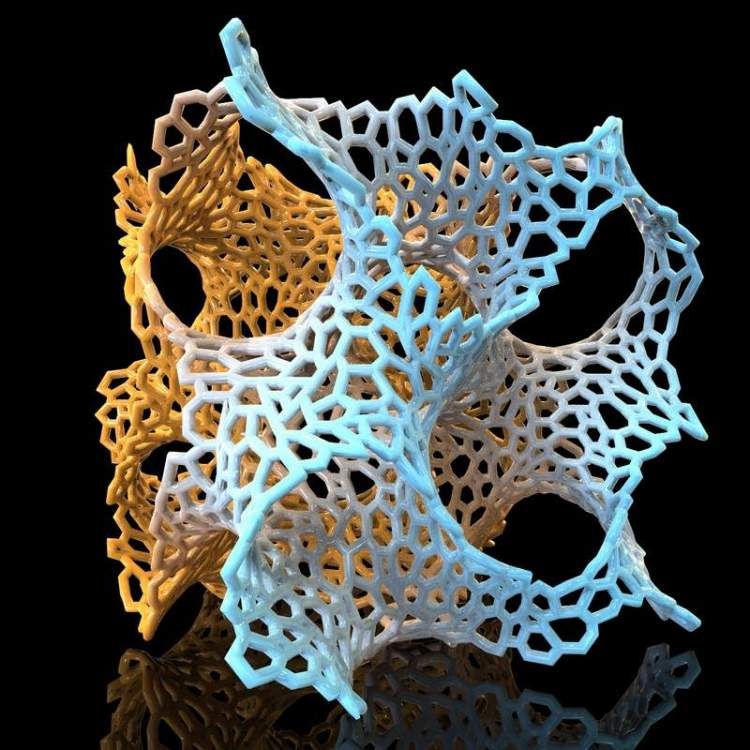

The 3D printers available today use a variety of materials ranging from plastics to ceramics, and from metals to hybrid materials. The technology is evolving at a breathtaking pace. For example, MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory recently developed a 3D printing technique to print both solid and liquid materials at the same time using a modified off-the-shelf printer, opening up a huge range of possible future applications.

3D printing technology is evolving at a breathtaking pace, with applications in areas ranging from food and fashion to regenerative medicine and prosthetics.

The expanding range of materials used for 3D printing means that the technology’s application is having an impact on a whole range of industries, fostering new opportunities for innovation and business development.

Even food is being 3D printed! It makes it possible to automate certain time-consuming aspects of food preparation and assembly, makes it easier to create freshly made snacks, has huge scope for food customization and can convert alternative ingredients like proteins from algae, beet leaves and insects into tasty meals! (Photo: Courtesy of www.naturalmachines.com).Within the medical field, for example, researchers at the National University of Singapore have found a way to print customizable tablets that combine multiple drugs in a single tablet, so that doses of medicines are perfectly adapted to the needs of individual patients. 3D printing is also making its mark in the fashion industry, as evidenced by the unveiling at New York Fashion Week in September 2016 of “Oscillation”, a multi-colored 3D-printed dress by threeASFOUR and New York-based designer Travis Finch. Even the agro-food industry is exploring the potential of 3D printing for customized food products.

3D printing is also making its mark in the fashion industry, as evidenced by the unveiling at New York Fashion Week in September 2016 of “Oscillation”, a multi-colored 3D-printed dress by threeASFOUR and New York-based designer Travis Finch. Even the agro-food industry is exploring the potential of 3D printing for customized food products.

Materialise’s consumer 3D printing service, i.materialise, featured in

the fashion show of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp,

Belgium, in 2016. The sunglasses are fully 3D printed “as a total

concept with no need for hinges or assembly” (Photo: Courtesy

of i.materialise.com).

The potential advantages of 3D printing are numerous for innovation-intensive companies. In particular, 3D printing allows them to reduce their overheads when developing, designing and testing new products or improving existing ones. They no longer have to pay for costly prototypes but can rapidly and cheaply undertake multiple iterations of complex elements in-house using 3D printers.

They no longer have to pay for costly prototypes but can rapidly and cheaply undertake multiple iterations of complex elements in-house using 3D printers.

Recognizing the transformative potential of 3D printing, many countries have already adopted, albeit unevenly, different strategies to create an economic and technological ecosystem that favors its development. The European Commission, for example, has identified 3D printing as a priority area for action with significant economic potential, especially for innovative small businesses.

Lawyers in many countries are considering the capacity of existing legal provisions to orient this new technology, particularly with respect to intellectual property (IP). 3D printing technology affects virtually all areas of IP law: copyright, patent law, design law, and even geographical indications. The question is, can IP laws in their current form embrace such an all-encompassing technology or do they need to be reformed? Does existing IP law ensure adequate protection for those involved in 3D printing processes and the products they make? Or would it make sense to consider creating a sui generis right for 3D printing to address emerging challenges, along the lines of arrangements in place in some jurisdictions for the protection of databases?

How current IP law handles 3D printingOne of the main concerns about 3D printing is that its use makes it technically possible to copy almost any object, with or without the authorization of those who hold rights in that object. How does current IP law address this?

How does current IP law address this?

Protecting an object from being printed in 3D without authorization does not raise any specific IP issues as such. Copyright will protect the originality of a work and the creator’s right to reproduce it. This means that if copies of an original object are 3D printed without authorization, the creator can obtain relief under copyright law. Similarly, industrial design rights protect an object’s ornamental and aesthetic appearance – its shape and form – while a patent protects its technical function, and a three-dimensional trademark allows creators to distinguish their products from those of their competitors (and allows consumers to identify its source).

Conventional eyeware design usually begins with the frameinto which corrective lenses are fitted. This can have a negative

impact on lens alignment and performance. With custom

software developed by Materialise, the Yuniku platform uses

3D scanning, parametric design automation and 3D printing to

design the customer’s chosen frame around the optical lenses

they require for a perfect look and fit.

(Photo: Courtesy of i.materialise.com)

Many commentators believe that a 3D digital file may also be protected under copyright law in the same way that software is. The justification for such protection is that “the author of a 3D file must make a personalized intellectual effort so that the object conceived by the author of the original prototype can result in a printed object,” notes French lawyer Naima Alahyane Rogeon. With this approach, the author of a digital file that is reproduced without authorization could claim a moral right in the work if their authorship is called into question. Article 6bis of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, which establishes minimum international standards of protection in the field of copyright, states that the author has “the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation. ”

”

If the printed object is protected by a patent, certain national laws, for example the Intellectual Property Code of France (Article L 613-4), prohibit supplying or offering to supply the means to use an invention without authorization. Following this approach, patent owners should be able to seek redress from third parties for supplying or offering to supply 3D print files on the grounds that these are an “essential element of the invention covered by the patent”.

What is the situation for hobbyists?But what is the situation with respect to hobbyists who print objects in the privacy of their own home? Are they at risk of being sued for infringement?

The standard exceptions and limitations that exist in IP law also naturally apply to 3D printing. For example, Article 6 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS), which has been transposed into EU law (EU Directive 2008/95/CE, Article 5), limits trademark protection to use “in the course of trade”. Similarly, with respect to patent law Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement states that member countries “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent”. Some national laws consider that the rights of the patent holder do not include acts performed in private for non-commercial purposes. In other words, when an object that is protected by a trademark or a patent is printed for purely private use, it is not considered an infringement of IP rights.

Similarly, with respect to patent law Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement states that member countries “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent”. Some national laws consider that the rights of the patent holder do not include acts performed in private for non-commercial purposes. In other words, when an object that is protected by a trademark or a patent is printed for purely private use, it is not considered an infringement of IP rights.

Travis Fitch, 3D printed by Stratasys, a leading 3D print solutions

company based in the United States, was unveiled at New York Fashion

Week in September 2016. “3D printing is transformative for designers

aiming to take complex designs and realize them as a wearable garment,”

explains threeASFOUR’s Adi Gil (Photo: Elisabet Davids, Jan Klier).

In the area of copyright, the rights granted to authors can be limited according to the so-called three-step test. Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement states that “members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.” Accordingly, some countries have established a “right to private copying” authorizing a person to reproduce a work for private use. Countries often then levy a fee on storage devices to compensate any losses incurred by the rights holder; some countries are exploring the idea of levying a fee to offset private 3D copying. However, some lawmakers consider it premature to extend such a fee to 3D printing, as this would constitute “an inadequate response or even a negative message for companies” and would put a brake on the development and uptake of 3D printing.

IP law in its current form, therefore, appears sufficient to effectively protect both 3D files and those using 3D printing technologies for non-commercial purposes. That said, the specificities of the 3D printing process mean that there are a number of questions that the courts will inevitably need to address. For example, who owns an object when it is first conceived by one individual, digitally modeled by another, and printed by a third? Can the person who designed the work and the person who digitally modeled it be considered co-authors of a collaborative work under copyright law? And if the object qualifies for patent protection, would these same individuals be considered co-inventors?

Other important questions include the type of protection that should be available to owners of 3D printers. Since their financial investment enables the creation of an object, might they qualify for the same type of related rights protection as that enjoyed by music producers whose investment enables the creation of sound recordings? And is the digitization of a pre-existing object considered an act of infringement simply because it is printed or its base file is loaded onto an online sharing platform for downloading? These issues still need to be ironed out.

In the meantime, to curb unauthorized use, if the object is protected by copyright, rights holders can make use of technological protection measures, the circumvention of which is expressly forbidden under the WIPO Copyright Treaty (Article 11). These measures make it possible, for example, to mark an object and its associated 3D print file with a unique identifier to monitor use.

Close collaboration between rights holders and 3D printer manufacturers in applying these measures to models intended for 3D printers could be beneficial. Similarly, partnerships with sharing platforms that make 3D files publicly available could help curb unauthorized use.

With such measures in place, it would be possible to set up a legal offering of downloadable 3D print files or 3D-printed objects. While online 3D printing services such as i.materialise are now readily available, one can imagine that their future evolution will follow that of online music delivery with the emergence of subscription models that allow users to download 3D print files in return for a monthly fee. Indeed, these are already available for 3D printing software, for example through Fusion 360, Autodesk’s cloud-based product innovation platform.

Indeed, these are already available for 3D printing software, for example through Fusion 360, Autodesk’s cloud-based product innovation platform.

Benjamin Hubert from the Layer design agency. The GO

wheelchair prototype was developed in collaboration with

Materialise, a leading 3D print software, engineering

and services provider based in Belgium

(Photo: Courtesy of i.materialise.com).

The experience of online music streaming platforms suggests that such arrangements could have a positive impact on infringement levels. The 2016 Australian Consumer survey on Online Copyright Infringement, for example, showed a 26 percent decrease in the number of Australian internet users accessing unlawful content online and a marked increase in the uptake of streaming services.

3D printing technologies have many life-enhancing, even revolutionary, applications, from regenerative medicine to prosthetics and from complex airplane components to food and fashion. As the use and application of this exciting technology gathers pace and digital transformation continues to gain momentum, 3D printing is likely to become deeply embedded in our daily lives. Beyond the IP-related questions outlined above, the use of 3D printing raises other important legal questions, for example in relation to quality assurance, legal liability and public order. All of these issues still need to be resolved and they can be.

As the use and application of this exciting technology gathers pace and digital transformation continues to gain momentum, 3D printing is likely to become deeply embedded in our daily lives. Beyond the IP-related questions outlined above, the use of 3D printing raises other important legal questions, for example in relation to quality assurance, legal liability and public order. All of these issues still need to be resolved and they can be.

But as the potential of this fascinating technology continues to unfold, the real challenge will be to fully understand the implications of its uptake and use on manufacturing processes across the economy and its impact on our daily lives.

Related Links

- 3D Printing Is Here to Stay!

3D printing - who is responsible for a defective item printed on a 3D printer?

For 3D printing, a CAD file (computer-aided design file) must be installed in the printer - a technical drawing that is read by the printer and contains a design of the object to be printed.

3D printing could be a revolutionary technology because it is decentralized and cheap, and in the near future everyone will be able to order 3D printing by sending a CAD file over the Internet to a 3D printing service provider. At the same time, this technology can also cause a number of problems in connection with the verification of the finished product, the possibility of counterfeiting, and risks associated with cybersecurity. From a legal point of view, the main problems are related to the protection of intellectual property rights, as well as the assessment of liability.

Since the whole process is decentralized, this means that one person can design a CAD file, another person can print it, and a third person can use the product. All of this makes it very difficult and confusing to meet security and compliance requirements from a legal standpoint.

Intellectual property rights protection

To properly address the legal issues associated with 3D printing, we must distinguish between (a) the protection of the CAD file (the result of the creative process) and (b) the protection of the finished printed product (the distribution process) . A CAD file consists of data compiled using CAD software (such as AutoCAD). They are usually in .DWG format, which can be imported into a PDF file.

A CAD file consists of data compiled using CAD software (such as AutoCAD). They are usually in .DWG format, which can be imported into a PDF file.

The data cannot be protected by the Copyright Act, only by trade secret protection. In Europe, software protection is provided by copyright. Copyright owner, i.e. the creator can always protect his rights in a way that suits him. The issue of extending copyright protection in relation to a CAD file is questionable if it is not related to artistic creation. Still, the CAD file can be protected by the database sui generis if it can be shown that the collection of the applied data set required significant effort.

During the distribution process, if the physical object is already printed and ready for distribution, the legal approach is different from the analysis applied to the CAD. In this case, copyright protection is no longer valid, and industrial property rights such as patents and design protection provide the most effective protection. Why is this happening? The actual creator of the printed object cannot be the person who orders the machine to print. The creator is the person who created the design/project contained in the CAD file. In the event that a designer/creator wants to extend protection to all creativity and dissemination, this can only be done through a patent or design protection.

Why is this happening? The actual creator of the printed object cannot be the person who orders the machine to print. The creator is the person who created the design/project contained in the CAD file. In the event that a designer/creator wants to extend protection to all creativity and dissemination, this can only be done through a patent or design protection.

Once all the requirements for patent protection have been met (technical development, innovativeness, level of invention and industrial applicability), the entire process can be patented in the name of its creator, i.e. in this case, the inventor. It is important to note that it is not possible to patent software as such in Europe. The possibility of patenting the functional characteristics of the software is determined by the presence of a technical innovation - the technical level must be different from the current technical level.

The second option for protecting printed objects is design protection, which prevents others from copying a product with the same shape and configuration. For more effective protection, it is important to register the rights to the design.

For more effective protection, it is important to register the rights to the design.

This means that the legal rules associated with 3D printing existed long before the possibility of 3D printing, and they apply to and protect the entire manufacturing process. All legal aspects related to intellectual and industrial property in Europe are suitable for the regulation of such technology. However, the most serious problem is that in each case the solutions are different. For this reason, it is always necessary to analyze each case individually in order to be sure of the rights of the creator/owner/inventor/designer.

Considering all the variables associated with 3D printing rights, it is recommended to take all possible preventive measures so that any individual case can be predicted. In this regard, it is important when licensing rights to have clear, binding terms and a license agreement that will help regulate the resolution of disputes arising in connection with 3D printing. In this way, for example, liability can be waived from the creator of the CAD file.

In this way, for example, liability can be waived from the creator of the CAD file.

Consumer protection

In the case of privately owned 3D printers, there may be a defect liability and/or product warranty issue as between the creator of the CAD file and the end user, there is no manufacturer that could act as an intermediary. This can have serious implications for consumer protection.

Who is responsible for a defective finished product? In a situation where the object was printed at home, the fault may lie with: a) the creator of the CAD file; b) a 3D printer seller; or c) a print material seller. If one of them is a legal entity, the consumer protection authority can help the consumer and hold accountable those responsible for the marriage of the product. If the seller of the defective product is an individual, it will be much more difficult for the consumer to prove that the defect arose at a particular stage.

The second problem that concerns consumers of 3D printing technology is that when they use the goods and services offered by companies, the conditions for their use are always set in advance and cannot be changed.

Intellectual Protection Facts

| Intellectual property | Protection | Owner | |

| Database | |||

October

Author: Matthew Rimmer *, Professor of the Law in the field of intelligent property and intelligent property Innovation Department of Law, Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, Australia

3D printing is a branch of technology based on the principle of additive manufacturing (as opposed to the principle of subtractive manufacturing that underlies the traditional manufacturing industry). 3D printing is also associated with the Craftsmen Movement, a social movement whose main idea is to develop designs for various products and share them.

3D printing is currently in transition. The consumer "3D printing revolution", which aimed to have a 3D printer in every home, has failed. MakerBot, a pioneer in 3D printing, is having trouble with its changing approach to intellectual property (IP) issues, disrupting its ties to the open source software community, and the user audience turned away from it. As former MakerBot CEO Bre Pettis said in an interview, "The open source community has kicked us out of their paradise." As a result, MakerBot was acquired by Stratasys, a leader in the 3D printing industry, which restructured and repurposed it.

Some other key players also went bankrupt. In particular, TechShop, a membership-funded and open-to-all network of studio-workshops for home craftsmen, went bankrupt. Maker Media, which publishes Make magazine and hosts craft festivals in the United States, has gone under external control. Make magazine founder Dale Doherty is trying to revitalize his project with a new structure he created called Make Community LLC.

Maker Media, which publishes Make magazine and hosts craft festivals in the United States, has gone under external control. Make magazine founder Dale Doherty is trying to revitalize his project with a new structure he created called Make Community LLC.

Industrial 3D printing continues to grow

While personal 3D printing has not developed as expected, there has been growth in a number of other forms and categories of 3D printing. Along with robotics and big data, 3D printing has become one of the promising technologies in the manufacturing industry. Companies specializing in information technology and design are working to improve the way 3D printing is used. Significant investments, especially from transport companies, have been attracted by the technology of 3D printing of metal products. In addition, there have been large-scale experiments related to the application of 3D printing in the healthcare sector, including 3D printing in dentistry, 3D printing in medicine, and bioprinting.

As technology improves and develops, there have been several cases of lawsuits being filed in the courts, as well as certain political developments regarding the regulation of the 3D printing industry. Our recently published book 3D Printing and Beyond explores some of the major developments in IC and 3D printing. In particular, it analyzes the issues of 3D printing in relation to areas such as copyright law, trademark law, patent law, and trade secrets (as well as some of the broader issues related to the regulation of 3D printing). In addition, the book highlights the use of open licensing mechanisms in the field of 3D printing.

3D printing and copyright law

A few years ago, there was a panic that the widespread use of 3D printing would lead to a wave of large-scale infringements of authors' rights, similar to the situation that arose with the advent of the Napster file-sharing network . Although such fears have not yet materialized, there have been various conflicts related to copyright and 3D printing. For example, Augustana College (United States) objected to 3D scanning of Michelangelo's statues, even though they were not subject to copyright protection and were clearly in the public domain. The American cable television network HBO has blocked the sale of an iPhone stand in the form of an "iron throne" from the TV series "Game of Thrones", made according to the drawings of designer Fernando Sosa using 3D printing. United States singer-songwriter Katy Perry has demanded a ban on the sale of a 3D-printed "shark on the left" figure by the same designer (nevertheless, this product subsequently reappeared in the Shapeways 3D Printing Systems catalog). The heirs of the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp opposed the production of a 3D-printed set of chess pieces based on the works of this artist.

For example, Augustana College (United States) objected to 3D scanning of Michelangelo's statues, even though they were not subject to copyright protection and were clearly in the public domain. The American cable television network HBO has blocked the sale of an iPhone stand in the form of an "iron throne" from the TV series "Game of Thrones", made according to the drawings of designer Fernando Sosa using 3D printing. United States singer-songwriter Katy Perry has demanded a ban on the sale of a 3D-printed "shark on the left" figure by the same designer (nevertheless, this product subsequently reappeared in the Shapeways 3D Printing Systems catalog). The heirs of the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp opposed the production of a 3D-printed set of chess pieces based on the works of this artist.

3D printing was also subject to the on-demand removal of content under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (USA). Shapeways and a number of other 3D printing firms have raised concerns about the implications of this regime for online platforms and 3D printing intermediaries.

Shapeways and a number of other 3D printing firms have raised concerns about the implications of this regime for online platforms and 3D printing intermediaries.

In addition, discussions took place on issues related to the use of technical protection measures in the context of copyright law and 3D printing. For example, the US Copyright Office has confirmed a limited technical protection exception for 3D printing stocks.

3D printing and design law

Developments in 3D printing have also raised the issue of product repair rights.

Efforts have been made across the European Union to recognize the right to repair in order to support consumer rights and develop a circular economy. In this regard, one of the important factors in achieving changes in the behavior of companies and consumers has become the European Greening Directive (Directive 2009/125/EC).

In July 2019, the United States Federal Trade Commission held a Hearing on "Can't be Repaired: A Workshop on Product Repair Restrictions. " Significant differences remain between IP owners and right-to-repair advocates in the United States. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has called for legislation to secure the right to repair for the benefit of farmers in the agricultural regions of the United States.

" Significant differences remain between IP owners and right-to-repair advocates in the United States. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has called for legislation to secure the right to repair for the benefit of farmers in the agricultural regions of the United States.

Significant and first-of-its-kind litigation in Australia regarding right to repair under Design Law ( GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S 6 . . - S - Auto Parts Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 97). The Australian Treasury is considering policy options regarding the practice of sharing vehicle repair information.

Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Consumer Affairs Minister Shane Rettenbury called for recognition of the right to repair from the rostrum of the Consumer Affairs Forum, which includes ministers from both Australia and New Zealand. Federal Minister Michael Succar asked the Australian Productivity Commission to look into the matter.

Calls for right-to-repair laws, both at the provincial and federal levels, are also being heard in Canada. As Laura Tribe, Executive Director of Open Media, noted in this regard, “We are committed to ensuring that people have the opportunity to be the real owners of the products they own.”

3D printing and trademark law

3D printing also brings uncertainty to trademark law and related legal regimes, including product substitution, identity rights, commercial use of characters, and trade dress. The legal conflict surrounding Katy Perry's trademark application for the "shark on the left" image provides some insight into some of the issues that arise in this regard.

Regarding bioprinting, Advanced Solutions Life Sciences sued Biobots Inc. In connection with the alleged violation of its trademark rights ( Advanced Solutions Life Sciences LLC V Biobiots . Advanced Solutions Life Sciences owns and uses the registered trademark Bioassemblybot for 3D bioprinting and tissue growth.

3D printing and patent law

According to the 2015 WIPO Global Intellectual Property Report "Breakthrough Innovation and Economic Growth", the number of 3D printing patent applications is steadily increasing. Some industrial 3D printing companies, including 3D Systems and Stratasys, have managed to build large 3D printing patent portfolios. Large industrial companies, including GE and Siemens, have also accumulated significant patent assets in 3D printing and additive manufacturing. Information technology companies, including Hewlett Packard and Autodesk, also play an important role in the 3D printing industry.

With the growing commercial importance of 3D printing in the manufacturing industry, there have been a significant number of litigations related to 3D printing of metal products. In July 2018, as part of the “Desktop Metal Inc.” v. Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018 Case No. 1:18-CV-10524), a federal jury found that Markforged Inc. did not infringe two patents owned by rival Desktop Metal Inc. (See Desktop Metal Inc. v. Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018) 2018 WL 4007724 (Massachusetts District Court, jury verdict). In this regard, the CEO of Markforged Inc. .” Greg Mark stated, “We are pleased with the jury's verdict that we have not infringed patents and that Metal X technology, which is the latest addition to the Markforged 3D printing platform, is based on our own Markforged's proprietary designs." For its part, a spokesman for Desktop Metal noted that it was "satisfied that the jury recognized the validity of all claims in both Desktop Metal patents, which were discussed in a lawsuit against the company "Markforged"

(See Desktop Metal Inc. v. Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018) 2018 WL 4007724 (Massachusetts District Court, jury verdict). In this regard, the CEO of Markforged Inc. .” Greg Mark stated, “We are pleased with the jury's verdict that we have not infringed patents and that Metal X technology, which is the latest addition to the Markforged 3D printing platform, is based on our own Markforged's proprietary designs." For its part, a spokesman for Desktop Metal noted that it was "satisfied that the jury recognized the validity of all claims in both Desktop Metal patents, which were discussed in a lawsuit against the company "Markforged"

In 2018 (after the above verdict) Desktop Metal Inc. and Markforged Inc. entered into a confidential financial agreement that settled all other litigation between them. However, in 2019 Markforged Inc. filed another lawsuit against Desktop Metal Inc. due to the fact that, according to her, the latter violated that part of the agreement, which concerned non-disclosure of negative information.

3D printing and trade secrets

In addition, the first litigation regarding 3D printing and trade secret legislation took place. In 2016, Florida-based 3D printing startup Magic Leap filed a lawsuit in federal court for the Northern District of California against two of its former employees for misappropriation of trade secret information within the meaning of Trade Secret Protection Act (“ Magic Leap Inc ." v Bradski et al (2017) case no. 5:16-cvb-02852). In early 2017, a judge granted the defendants' request to stay the case, stating that Magic Leap had failed to provide "a reasonable degree of specificity" to the disclosure of alleged trade secrets. Subsequently, the judge allowed Magic Leap to amend the text of its submission. In August 2017, the parties entered into a “confidential agreement” in connection with this issue. In 2019Mafic Leap sued the founder of Nreal for breach of contract, fraud, and unfair competition (Magic Leap Inc. v. Xu, 19-cv-03445, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (San Francisco)).

v. Xu, 19-cv-03445, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (San Francisco)).

3D printing and open licensing

In addition to proprietary IP protections, 3D printing has a widespread practice of open licensing. Companies with a free distribution philosophy include Prusa Research (Czech Republic), Shapeways (Netherlands-US) and Ultimaker (Netherlands). Members of the Craft Movement used open licensing mechanisms to share and distribute 3D printing files. As noted in The State of the Commons 2017, the Thingiverse platform was one of the most popular platforms using Creative Commons licenses.

Other issues arising from the development of 3D printing

In addition to IP issues, the development of 3D printing also raises a number of other legal, ethical and regulatory issues. In healthcare, regulators have faced challenges with personalized medicine. The United States Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Health Products Administration held consultations on the development of a balanced set of regulations for medical 3D printing and bioprinting. The European Parliament has adopted a resolution calling for a comprehensive approach to the regulation of 3D printing.

In healthcare, regulators have faced challenges with personalized medicine. The United States Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Health Products Administration held consultations on the development of a balanced set of regulations for medical 3D printing and bioprinting. The European Parliament has adopted a resolution calling for a comprehensive approach to the regulation of 3D printing.

Litigation regarding 3D printing of firearms is also ongoing in the United States. Several state attorneys general have sued the current administration to obstruct an agreement between the federal government and Defense Distributed. Several criminal cases have been filed in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and Japan in connection with attempts to 3D print firearms. Legislators are debating the feasibility of criminalizing crimes related to possession of digital blueprints for 3D printed firearms.

Footnotes

* Dr. Matthew Rimmer is Head of the KTU Research Program on Intellectual Property Law and Innovation and is involved in the KTU Research Center for Electronic Media, the KTU Australian Health Law Research Center and the KTU Research Program in International Law and global governance.