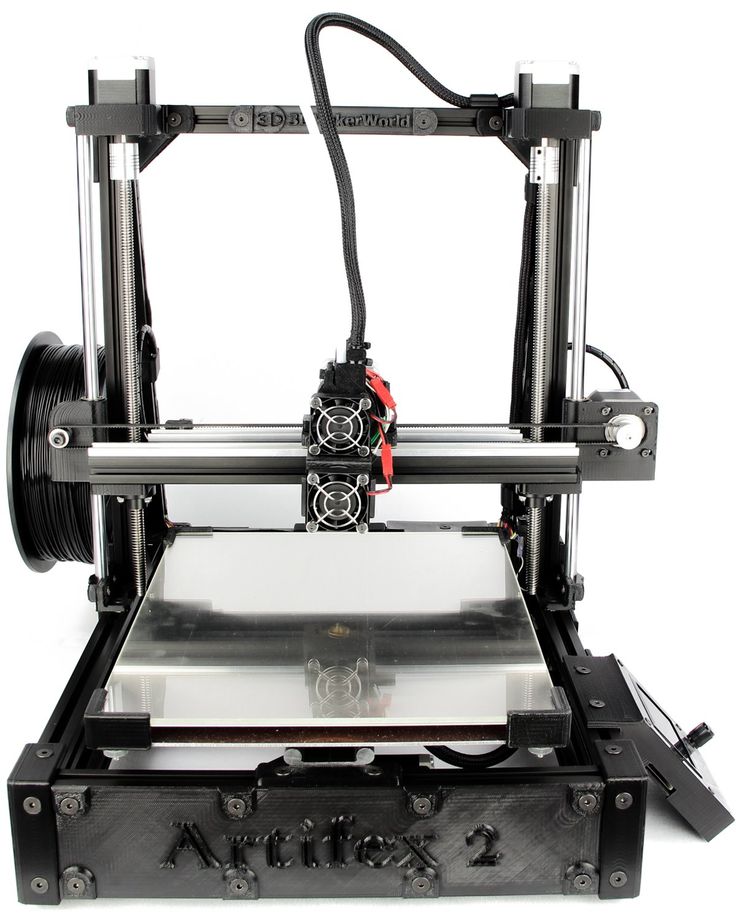

Ge 3d printing fuel nozzle

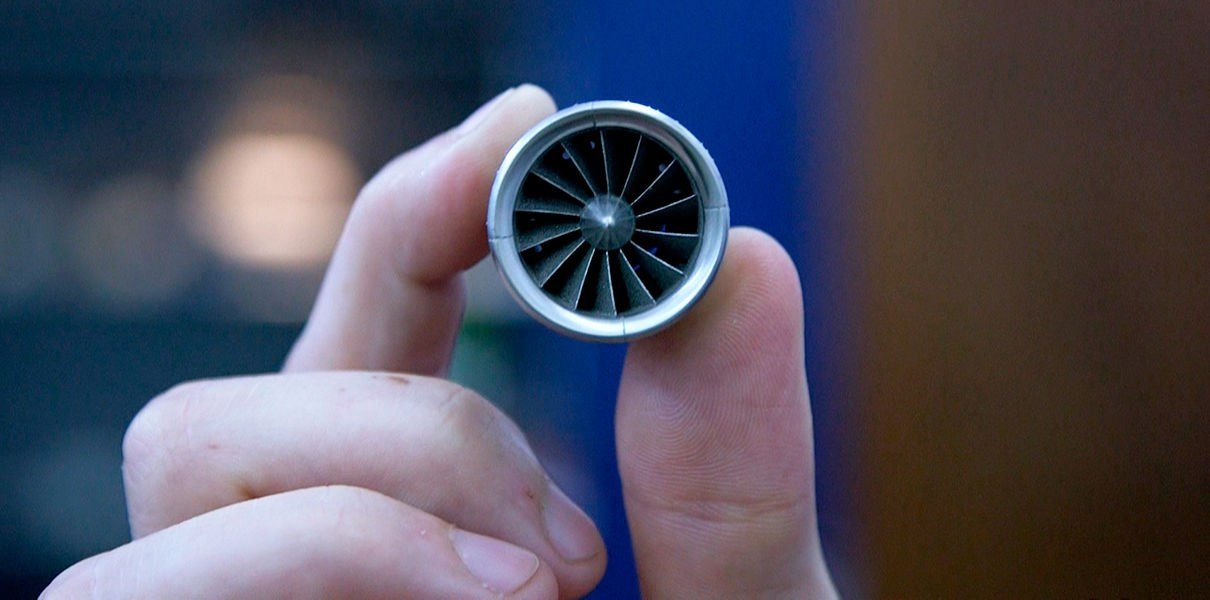

Transformation In 3D: How A Walnut-Sized Part Changed The Way GE Aviation Builds Jet Engines

A jet engine fuel nozzle doesn’t look like much. Shaped like a water faucet perched atop two stubby legs, it resembles a forgotten piece of plumbing equipment small enough to hold in the palm of a hand. Few would ever guess that this unimposing object is among the most disruptive pieces of technology in GE history — one that gave rise to the world’s best-selling commercial jet engines, ignited a new GE business unit and showed the world just what 3D printing can do.In just a few years, 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, has evolved from an alienlike technology confined mainly to labs to a bona fide manufacturing method ready for prime time. GE has already started using it to mass-produce parts for jet engines. In October, GE Aviation’s 3D-printing facility in Auburn, Alabama, produced its 30,000th fuel nozzle tip.

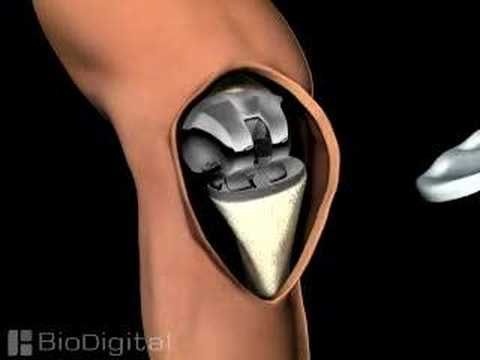

It all started a decade ago, when CFM International, a 50-50 joint venture between GE Aviation and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines, was developing the LEAP engine, a new commercial jet engine that promised to burn less fuel than existing engines and release fewer emissions. As ambitious plans for the engine unfolded, Mohammad Ehteshami, the head of engineering at GE Aviation at the time, quickly recognized its success rested in many respects on the labyrinthine passages inside the tip of the fuel nozzle, which is designed to mix jet fuel with air in the most efficient manner.

To get the job done right, Ehteshami assembled a top-notch team of engineers, including an amateur pilot named Josh Mook, then just 28 years old, whose work with turbine blades had caught Ehteshami’s attention. Before long, Mook and his colleagues came up with their dream variant, a walnut-sized object that housed 14 elaborate fluid passages.

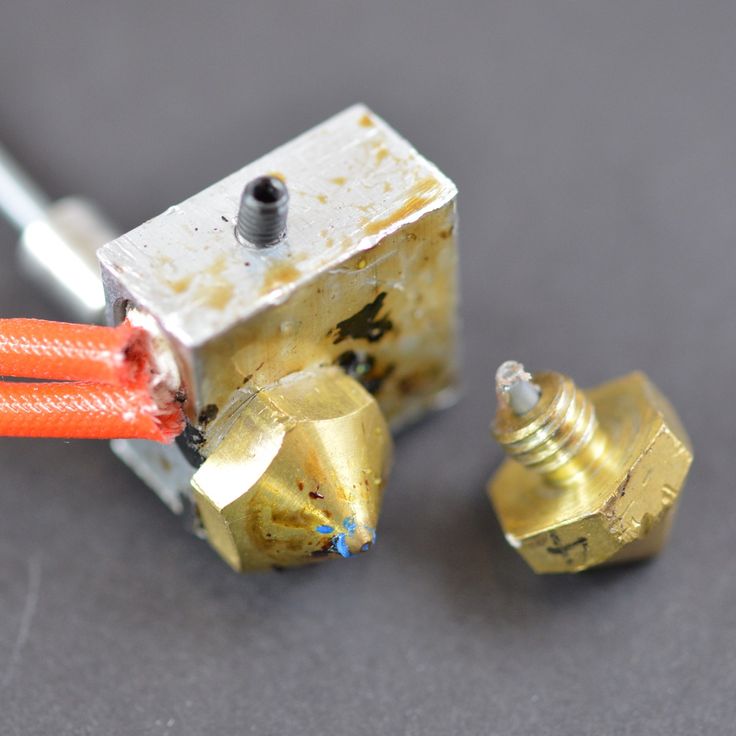

But as elegant as it was, the part arrived with a flaw: The tip’s interior geometry was too intricate. It was almost impossible to make. “We tried to cast it eight times, and we failed every time,” Ehteshami recalls.

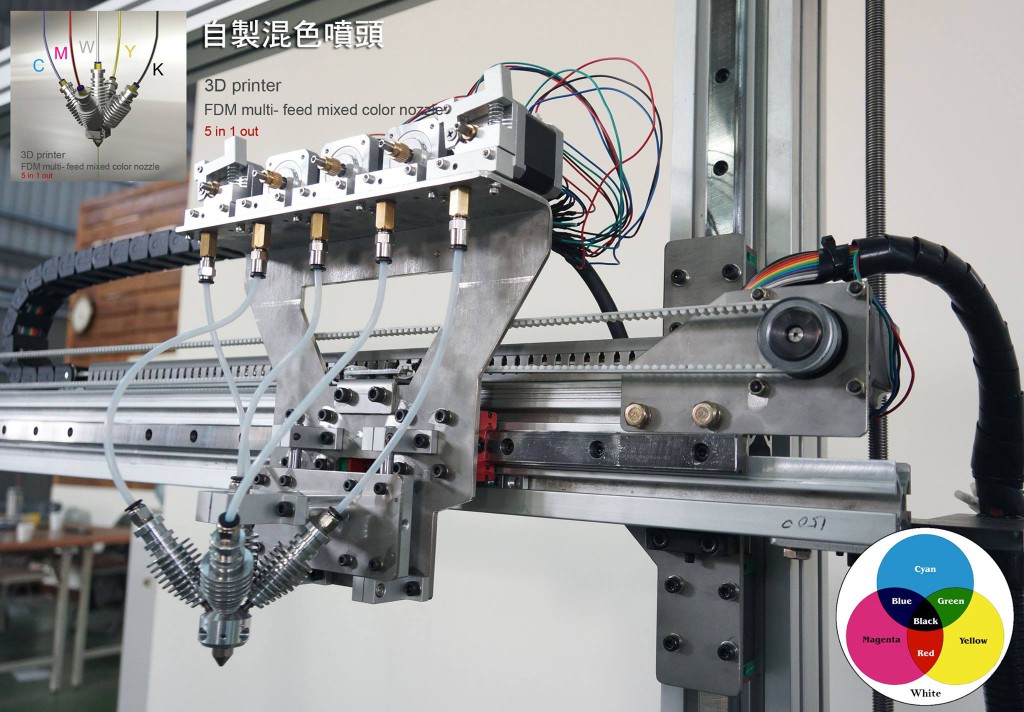

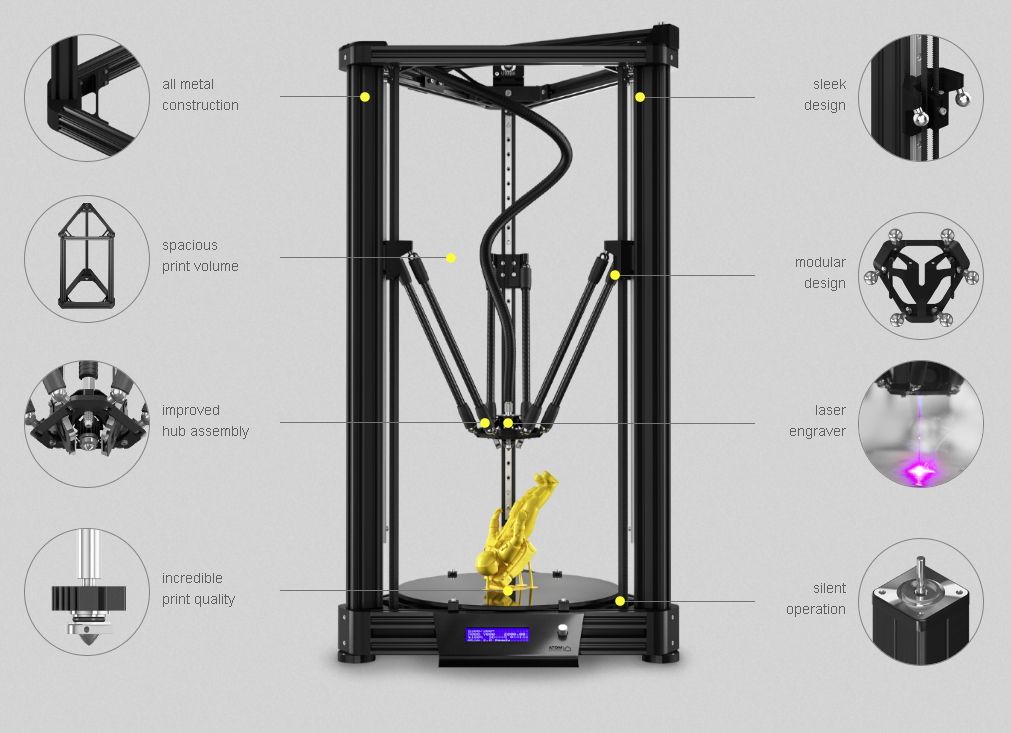

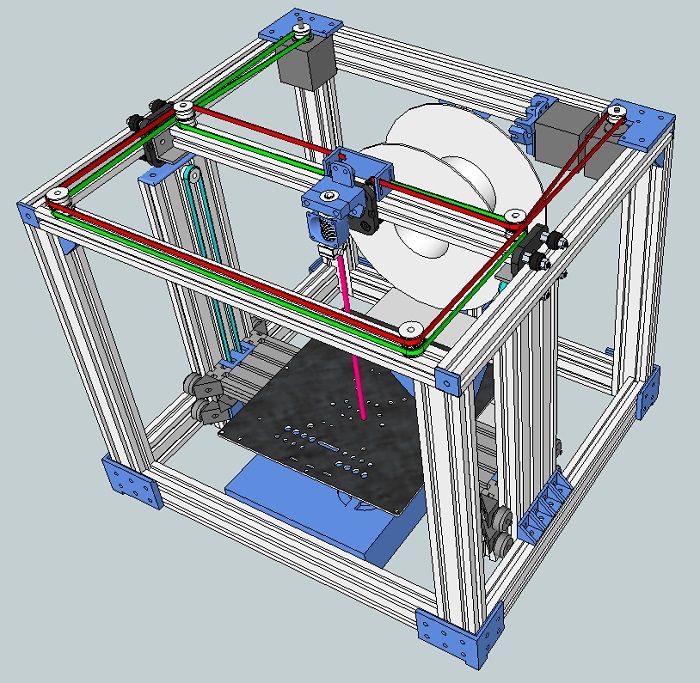

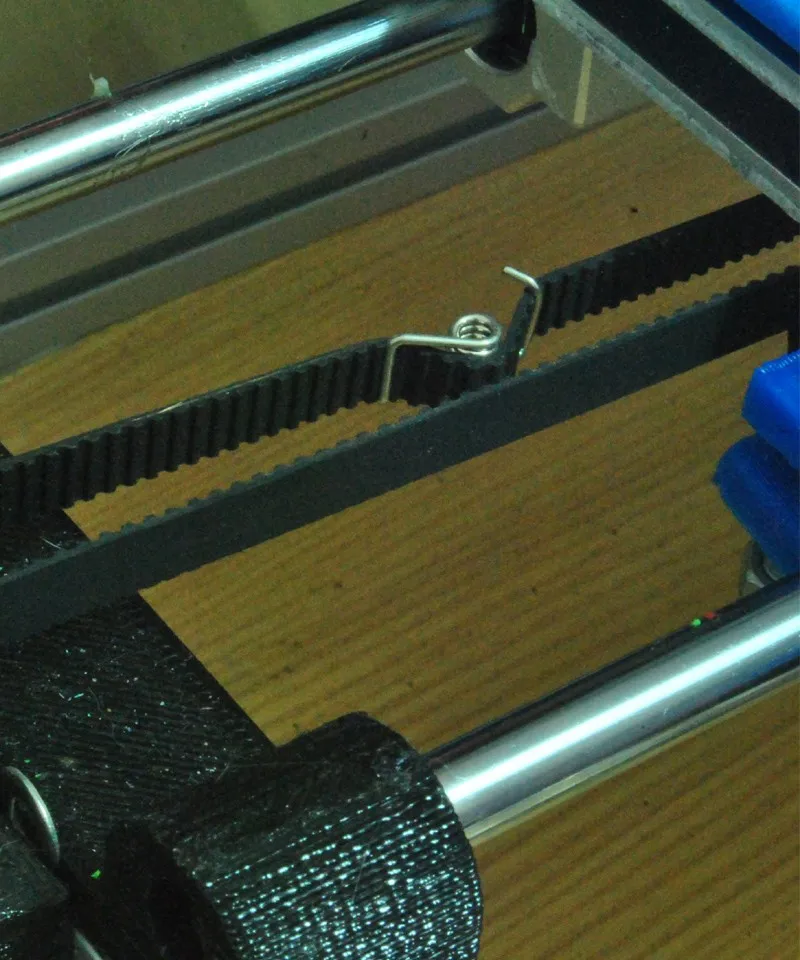

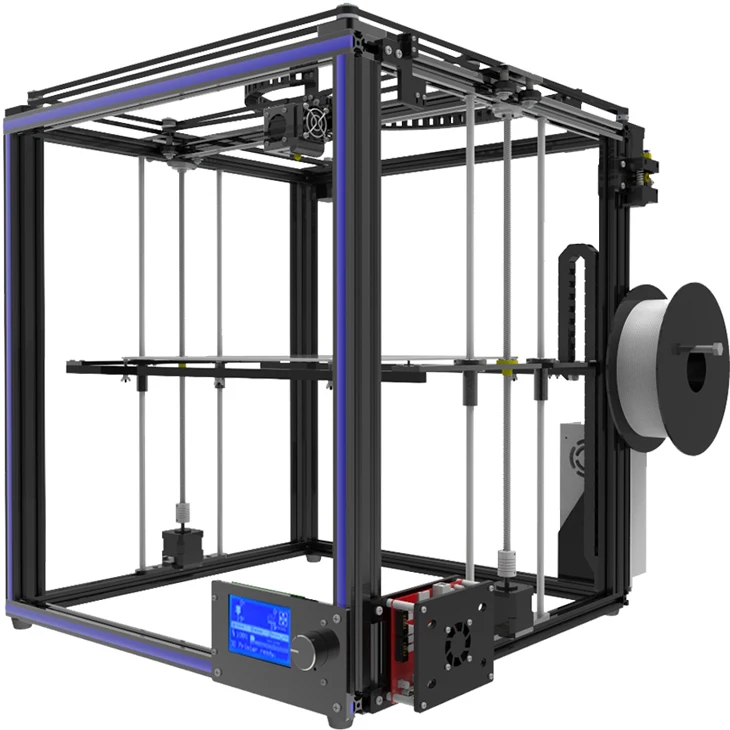

Traditional methods wouldn’t cut it, but 3D printing just might. A 3D printer functions like a laser pen, following a computer drawing and fusing layer upon layer of fine metal powder into the final shape. 3D printers can build complex, dense parts like the fuel nozzle while generating a fraction of the waste produced by conventional manufacturing. The catch: At the time, GE Aviation used additive manufacturing only for prototypes. It had never printed anything for commercial use, much less for an entire fleet of passenger airplanes.

For Mook, who obsessively tinkered with machines as a boy, this was the dream job. Working closely with 3D-printing pioneer Greg Morris — whose company GE eventually acquired — Mook helped re-engineer off-the-shelf 3D printers to meet the fuel nozzle’s specifications. Rather than 20 pieces welded together, the new tip was a single elegant piece that weighed 25 percent less than its predecessor, and was five times more durable and 30 percent more cost-efficient.

Rather than 20 pieces welded together, the new tip was a single elegant piece that weighed 25 percent less than its predecessor, and was five times more durable and 30 percent more cost-efficient.

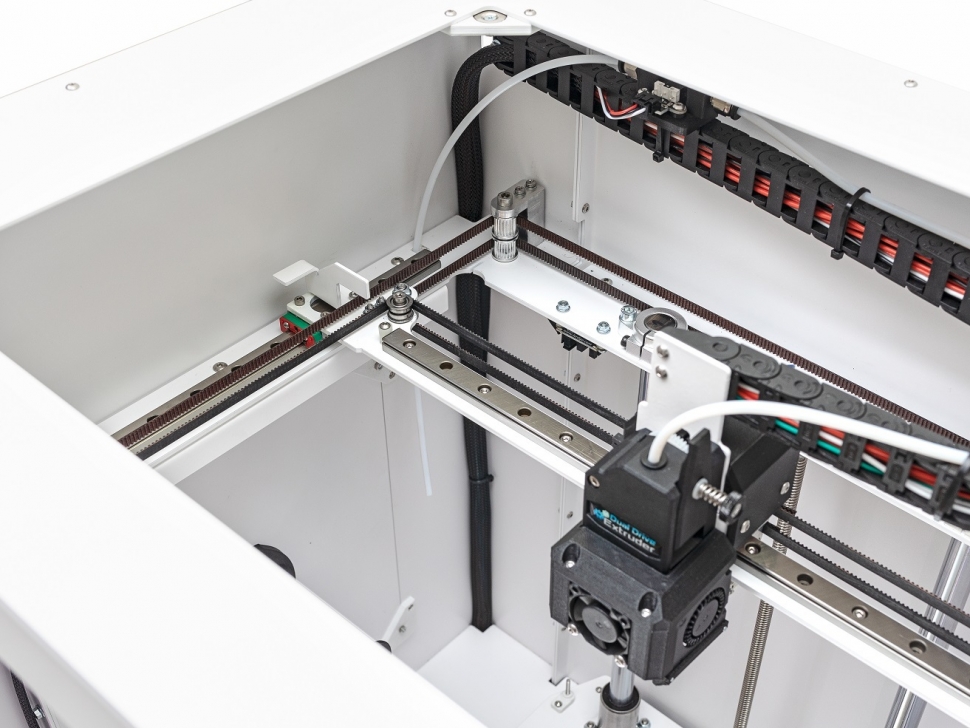

But the team was far from finished. They had to work fast to meet the LEAP program schedule and make sure that the Federal Aviation Administration certified the part. And with orders for the LEAP engine pouring in, GE Aviation needed to figure out how to get its 3D-printing operations ready for mass production. “People think 3D printing is as simple as operating an ink printer, but it’s not,” says Chris Schuppe, who runs GE Additive’s AddWorks team, a group of almost 200 engineering consultants dedicated to accelerating additive adoption for GE’s customers. “The fuel nozzle requires orchestrating over 3,000 layers of powdered metal that are about the thickness of a human hair.”

GE Aviation assembled a new team of roughly 100 employees, ranging from aviation experts to metallurgists, to hammer out these complex processes. That included making sure each machine was properly calibrated to handle the given product’s material properties — an arduous procedure that must be repeated every time a manufacturer adds a new machine to the production line.

And in 2015, it built the fuel nozzle a 3D-printing facility of its own, in Auburn. With more than 40 3D printers at the ready and a deep pool of talent from Auburn University, the plant delivered a total of 8,000 fuel nozzles in 2017. And, as of now, the total tally stands at over 33,000 3D-printed fuel nozzle tips.

There’s much to celebrate with this milestone. The factory supplies fuel nozzles for engines that power both the Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 MAX jets, with total orders for the LEAP engine exceeding 16,000, valued at more than $236 billion.

Beyond the LEAP engine, GE Aviation uses additive manufacturing to make sensors, blades, heat exchangers and other parts for engines like the GE9X, the world’s largest jet engine, developed for Boeing’s new 777X wide-body plane. The technology even broke into the small-aircraft industry with Catalyst, GE’s new turboprop engine. Engineers used 3D printing to replace 855 components with just a dozen.

But aviation is only the beginning. Today the automotive, energy, healthcare and other industries are embracing 3D printing. GE estimates that by 2020, its GE Additive unit will continue to increase its revenue from equipment, materials and services. Amazing what can grow out of one little walnut.

GE Aviation Produced Its 100,000th 3D Printed Fuel Nozzle Tip

Above: GE Aviation’s Auburn Facility/Image Source: GE AviationGE Aviation, an operating unit of GE and a world-leading provider of jet engines, revealed that its Auburn, Alabama, facility recently shipped its 100,000th 3D printed fuel nozzle tip for its CFM LEAP engine .

In Auburn, GE Aviation employees helped establish new processes to mass produce parts with 3D printing, then scaled the technology over time, while improving and maintaining production quality.

Above: GE Aviation’s Auburn Facility/Image Source: GE Aviation“We opened the industry’s first site for mass production using the additive manufacturing process, and to achieve this milestone affirms our plans and investments were on target. There is a bright and exciting future for this technology.”

– Eric Gatlin, additive general manager for GE Aviation

The Auburn site began producing 3D printed fuel nozzles in 2015 and was the industry’s first mass manufacturing site for producing aircraft engine parts using additive manufacturing.

The fuel nozzle was made for the CFM LEAP engine*, which entered revenue service in 2016 and surpassed 10 million flight hours earlier this year. The fleet is providing operators with 15% better fuel efficiency than previous generation engines. Each engine has 18 shrouds and 18 or 19 fuel nozzles, depending on the specific model.

Each engine has 18 shrouds and 18 or 19 fuel nozzles, depending on the specific model.

According to Andrea McAllister, plant leader for GE Aviation Auburn, “As GE grows the number of jet engine parts made with additive manufacturing methods, we expect to continue to advance our manufacturing capabilities right here in Auburn. We encourage those interested in helping build the future of flight with innovative technologies to join the GE Aviation team.”

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey applauded the achievement at the Alabama plant saying, “The remarkable milestone reached at GE Aviation’s Auburn facility isn’t just about producing 100,000 3D printed fuel nozzle tips – it also shows that Alabama workers are at the forefront of additive technologies revolutionising manufacturing through next-level innovation. This is an exciting development, and I look forward to seeing what GE Aviation and its Alabama workforce will be able to achieve in the future.”

“I’m excited to congratulate GE Aviation on the success they’ve seen here in Auburn and would like to thank them for their investment in our community.

– Mayor Ron AndersFor years, GE Aviation has been a steady source of high-quality jobs and high-tech production in Auburn. With the resources at Auburn University and their efforts in additive manufacturing research and training, we are excited about what this partnership will continue to bring in the future.”

The 3D printed fuel nozzle reduced the number of parts in a single fuel nozzle tip from 20 to only one. The weight was also cut by about 25%.

*LEAP engines are a product of CFM International, a 50/50 joint company between GE and Safran Aircraft Engines.

About Manufactur3D Magazine: Manufactur3D is an online magazine on 3D Printing. Visit our Global News page for more updates on Global 3D Printing News. To stay up-to-date about the latest happenings in the 3D printing world, like us on Facebook or follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter.

GE Aviation additive factory breaks thirty thousand 3D printed fuel injectors

News

Dedicated to the skeptics of mass-produced 3D printing! Employees at General Electric Corporation's Aviation Additive Manufacturing Center in Auburn celebrated a new milestone: the company recently brought its LEAP 3D-printed jet fuel injectors to 30,000.

nine0003

nine0003 “The essence of this achievement is not just the production of the 30,000th part. The team should be proud that they helped prove the viability of additive technologies in mass production to everyone who uses the developments of General Electric. We are paving the way for mass 3D printing for the benefit of industry and are constantly looking for new applications,” said Ricardo Acevedo, director of the GE Aviation additive factory in Auburn.

Auburn, Alabama is one of the fastest growing cities in the United States, and General Electric Corporation plays a role in this. The population of the city is relatively small, only about sixty thousand people. Approximately one-quarter of the working population works in one way or another in connection with Auburn University, and graduates of the university can find work at the nearby factories of South Korean automakers KIA and Hyundai, as well as at the facilities of General Electric. nine0003

nine0003

In 2015, the European concern Airbus opened an aircraft manufacturing plant in the Alabama city of Mobile. Aircraft engines are supplied by General Electric's aviation division, GE Aviation, which has opened several facilities in the same state, including a silicon carbide ceramics factory in Huntsville and an additive manufacturing center in Auburn. In 2014, the company invested about $50 million to equip the Auburn site with a dozen industrial 3D printers, after which it began pilot production of fuel injectors for the new generation of LEAP turbojet engines. nine0003

LEAP is now considered one of the best sellers of CFM International, a conglomerate of GE Aviation and the French holding Safran. The portfolio of orders today exceeds 16,300 power plants. The engines are available in three versions, designed to power the Airbus A320neo, Boeing 737 MAX and China's COMAC C919, which is still being tested. Compared to its predecessors, the CFM56 series engines, the new units provide an additional 15% fuel savings. Each engine is equipped with nineteen fuel injectors, and all of them are made in Auburn. nine0003

Each engine is equipped with nineteen fuel injectors, and all of them are made in Auburn. nine0003

One of the advantages of additive manufacturing nozzles is that 3D printing allows you to grow the entire product, combining 20 parts into a single unit without the need for assembly and welding, thereby increasing reliability and reducing labor costs. At the same time, the mass of nozzles is reduced by 25%.

Pilot additive manufacturing has already grown into serial production, and the fleet of industrial 3D printers has grown from ten to forty. Basically, these are additive installations manufactured by the German company Electro Optical Systems (EOS), operating on the technology of selective laser sintering of metal powder compositions (DMLS). nine0003

The company's staff includes 230 specially trained specialists. About seventy more will join the ranks next year. There is no need to look for professionals all over the country. They are being prepared here at Auburn University, allowing students to practice on a specially purchased EOS M290 3D printer, exactly the same as the equipment in the factory. Once employed, a novice technician can count on a monthly salary of two and a half thousand dollars.

They are being prepared here at Auburn University, allowing students to practice on a specially purchased EOS M290 3D printer, exactly the same as the equipment in the factory. Once employed, a novice technician can count on a monthly salary of two and a half thousand dollars.

Do you have interesting news? Share your developments with us, and we will tell the whole world about them! We are waiting for your ideas at [email protected].

Subscribe to the author

Subscribe

General Electric Corporation has delivered the 100,000th 3D printed fuel injector for the LEAP family of turbofan engines used on Airbus and Boeing aircraft. nine0003

General Electric's Additive Factory in Auburn, Alabama, operates as part of the GE Additive Division and manufactures components for GE Aviation, among other things. In particular, since 2015 the company has been producing 3D printed fuel injectors for CFM LEAP turbofan engines.

Developed by General Electric Corporation and France's Safran Aircraft Engines under the CFM International joint venture brand, these powerplants power Boeing 737 MAX and Airbus A321neo airliners, and another is designed to take China's COMAC C919.

LEAP engines have been in operation since 2016 and have accumulated more than ten million hours of service by the start of this year. Depending on the modification, each engine is equipped with eighteen or nineteen injectors. The nozzles are manufactured on industrial 3D printers using the technology of selective laser fusion of metal powder compositions (SLM).

GE Additive Alabama facility in 2016

The basis of the industrial park of the Alabama factory was originally made up of additive systems manufactured by the German company Electro-Optical Systems (EOS GmbH), but over the past few years, laser 3D printers from the German company Concept Laser GmbH, as well as cathode-beam 3D printers from the Swedish company Arcam AB . The latter are used, among other things, in the production of titanium aluminide turbine blades for GE9X turbofan engines. At the end of 2016, General Electric bought out a majority stake in Concept Laser and Arcam. nine0003

The latter are used, among other things, in the production of titanium aluminide turbine blades for GE9X turbofan engines. At the end of 2016, General Electric bought out a majority stake in Concept Laser and Arcam. nine0003

One hundred thousand - is it a lot or a little? Let's put it this way: on average, this is about twenty-three thousand products a year. The factory broke the mark of thirty thousand 3D printed nozzles three years ago.

“We opened the industry's first mass additive manufacturing factory, and this milestone proves that our calculations and investments were right. This technology has a bright and exciting future,” said GE Aviation CEO Eric Gatlin. nine0003

Do you have interesting news? Share your developments with us, and we will tell the whole world about them! We are waiting for your ideas at [email protected].

Article comments

More interesting articles

10

Subscribe to the author

Subscribe

Don't want

0003

Read more

five

Subscribe to the author

Subscribe

Don't want

Anodizing is a process aimed at creating protective oxide layers on the surfaces of products.