Finger 3d print

Assessment of body-powered 3D printed partial finger prostheses: a case study | 3D Printing in Medicine

- Case study

- Open Access

- Published:

- Keaton J. Young ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5597-73161,

- James E. Pierce1 &

- Jorge M. Zuniga1,2

3D Printing in Medicine volume 5, Article number: 7 (2019) Cite this article

-

11k Accesses

-

11 Citations

-

Metrics details

Abstract

Background

Traditional prosthetic fabrication relies heavily on plaster casting and 3D models for the accurate production of prosthetics to allow patients to begin rehabilitation and participate in daily activities. Recent technological advancements allow for the use of 2D photographs to fabricate individualized prosthetics based on patient anthropometrics. Additive manufacturing (i.e. 3D printing) enhances the capability of prosthesis manufacturing by significantly increasing production speed and decreasing production cost. Existing literature has extensively described the validity of using computer-aided design and 3D printing for fabrication of upper limb prostheses. The present investigation provides a detailed description of the development of a patient specific body-powered 3D printed partial finger prosthesis and compares its qualitative and functional characteristics to a commercially available finger prosthesis.

Case presentation

A 72-year old white male with a partial finger amputation at the proximal interphalangeal joint of the left hand performed a simple gross motor task with two partial finger prostheses and completed two self-reported surveys (QUEST & OPUS). Remote fitting of the 3D printed partial finger began after receipt of 2D photographs of the patient’s affected and non-affected limbs. Prosthetic fitting when using 3D printable materials permitted the use of thermoforming around the patient’s residual limb, allowing for a comfortable but tight-fitting socket. Results of the investigation show improved performance in the Box and Block Test when using both prostheses (22 blocks per minute) as compared to when not using a prosthesis (18 blocks per minute). Both body-powered prostheses demonstrated slightly lower task-efficiency when compared to the non-affected limb (30 blocks per minute) for the gross motor task. Results of the QUEST and OPUS describe specific aspects of both prostheses that are highly relevant to quality of life and functional performance when using partial finger prostheses.

Remote fitting of the 3D printed partial finger began after receipt of 2D photographs of the patient’s affected and non-affected limbs. Prosthetic fitting when using 3D printable materials permitted the use of thermoforming around the patient’s residual limb, allowing for a comfortable but tight-fitting socket. Results of the investigation show improved performance in the Box and Block Test when using both prostheses (22 blocks per minute) as compared to when not using a prosthesis (18 blocks per minute). Both body-powered prostheses demonstrated slightly lower task-efficiency when compared to the non-affected limb (30 blocks per minute) for the gross motor task. Results of the QUEST and OPUS describe specific aspects of both prostheses that are highly relevant to quality of life and functional performance when using partial finger prostheses.

Conclusion

The use of 3D printing exhibits great potential for the fabrication of functional partial finger prostheses that improve function in amputees. In addition, 3D printing provides an alternative means for patients located in underdeveloped or low-income areas to procure a functional finger prosthesis.

In addition, 3D printing provides an alternative means for patients located in underdeveloped or low-income areas to procure a functional finger prosthesis.

Background

Limb loss due to amputation is expected to reach nearly 3.6 million by the year 2050, which will have dramatically increased from the current 1.6 million in 2005 [1]. The majority of these amputations are considered minor amputations, as these individuals are losing only small appendages such as fingers or toes [2]. Amputation of the fingers in the upper limbs is a common occurrence and has significant implications on individuals overall function, coordination and quality of life. Loss of these appendages can reduce functional ability, resulting in difficulties performing activities of daily living (ADL) [3]. The use of prostheses has been shown to improve completion of ADLs, in addition to improving psychosocial self-esteem, body image, interlimb coordination with the contralateral limb and body symmetry [4, 5]. Despite this, prior literature found that nearly 70% of upper limb prosthetic users were unsatisfied with their prosthesis when completing ADLs [6]. In addition, it has been indicated that nearly 52% of upper limb amputees abandon their prosthetic devices due to the functional, aesthetic or other limitations [7]. In contrast to the reported figures of device abandonment, realistic rejection rates and non-usage have been estimated to be even greater due to the lack of communication between clinics and prosthetic non-users [8]. To reduce the large degree of device abandonment, it is recommended that prosthetic device fitting occur immediately or as quickly as possible following a surgical amputation, which may increase the acceptance rate of these devices [9]. Traditional prosthesis fabrication is a lengthy process that requires a certified prosthetist to make multiple castings of the affected limb using plaster, which can be both labor and material intensive. As traditional fabrication methods may not meet the rate at which prostheses must be manufactured, the need for an accelerated method of production presents itself.

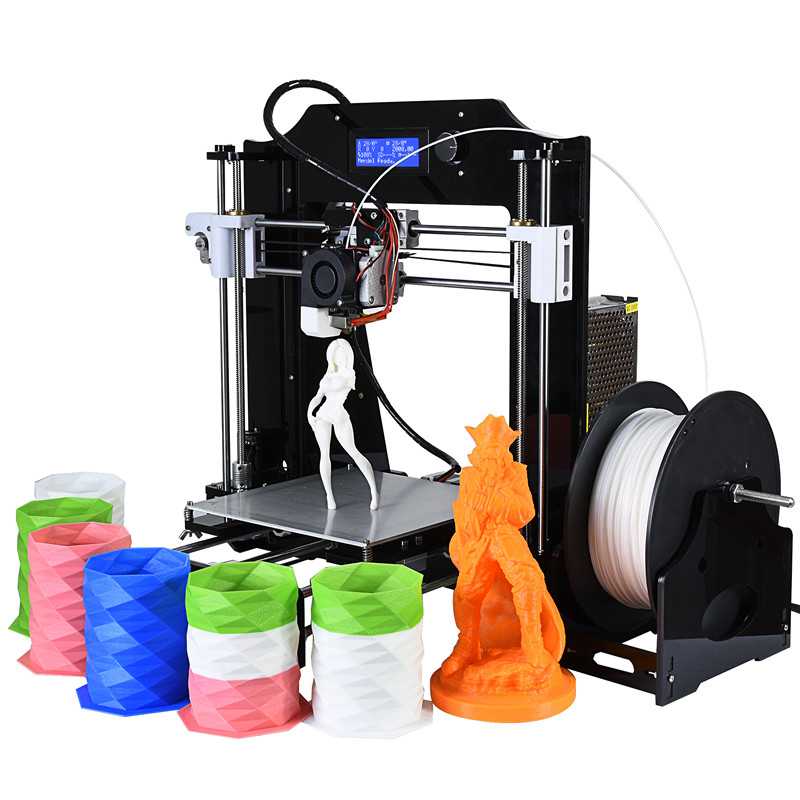

Despite this, prior literature found that nearly 70% of upper limb prosthetic users were unsatisfied with their prosthesis when completing ADLs [6]. In addition, it has been indicated that nearly 52% of upper limb amputees abandon their prosthetic devices due to the functional, aesthetic or other limitations [7]. In contrast to the reported figures of device abandonment, realistic rejection rates and non-usage have been estimated to be even greater due to the lack of communication between clinics and prosthetic non-users [8]. To reduce the large degree of device abandonment, it is recommended that prosthetic device fitting occur immediately or as quickly as possible following a surgical amputation, which may increase the acceptance rate of these devices [9]. Traditional prosthesis fabrication is a lengthy process that requires a certified prosthetist to make multiple castings of the affected limb using plaster, which can be both labor and material intensive. As traditional fabrication methods may not meet the rate at which prostheses must be manufactured, the need for an accelerated method of production presents itself. Modern advances in additive manufacturing (i.e., 3D Printing) have made it possible for the batch-production of low cost, customized upper-limb 3D prostheses using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), where the production capacity is limited to the size, type, and the total number of 3D printers available [10].

Modern advances in additive manufacturing (i.e., 3D Printing) have made it possible for the batch-production of low cost, customized upper-limb 3D prostheses using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), where the production capacity is limited to the size, type, and the total number of 3D printers available [10].

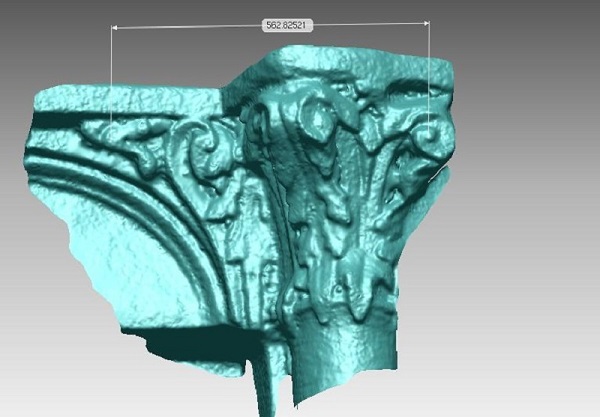

To reduce the time and inaccuracy of socket fabrication, 3D scanning has been previously utilized to scan the affected limb to allow for rapid prototyping of medical prostheses by producing accurate stereolithographic (STL) models, which are imported into computer-aided design (CAD) systems [11]. Socket fabrication using CAD methods have been shown to be reliable when coupled with digital files (i.e. STL’s) and additive manufacturing (i.e. FDM) reducing the amount of time needed to fabricate prosthetic sockets [12]. Furthermore, CAD systems have been shown to be a viable alternative for fabrication of functional 3D printable transitional prostheses with highly customized sockets relative to patient-specific anthropometrics [13]. Transitional prostheses are referred to as “temporary prosthesis” or “immediate postoperative prosthesis”, and have been previously investigated for retention and restoration of muscular strength and range of motion [14]. Therefore, the purpose of the present study is twofold: (i) to describe the development of a transitional 3D printed prosthesis for partial finger amputees and (ii) to discuss the qualitative and functional characteristics when compared to a commercially available partial finger prosthesis. This information is essential in creating a compelling argument for the efficacy of using 3D printed prostheses as transitional prosthetics for amputees with partial finger loss. We hypothesize that the locally fabricated 3D printed prosthesis will produce similar qualitative and functional results when compared to the commercially available partial finger prosthesis. Our hypothesis is based on previous investigations that have shown the use of 3D printing for the development of functional prostheses [13].

Transitional prostheses are referred to as “temporary prosthesis” or “immediate postoperative prosthesis”, and have been previously investigated for retention and restoration of muscular strength and range of motion [14]. Therefore, the purpose of the present study is twofold: (i) to describe the development of a transitional 3D printed prosthesis for partial finger amputees and (ii) to discuss the qualitative and functional characteristics when compared to a commercially available partial finger prosthesis. This information is essential in creating a compelling argument for the efficacy of using 3D printed prostheses as transitional prosthetics for amputees with partial finger loss. We hypothesize that the locally fabricated 3D printed prosthesis will produce similar qualitative and functional results when compared to the commercially available partial finger prosthesis. Our hypothesis is based on previous investigations that have shown the use of 3D printing for the development of functional prostheses [13].

Case presentation

Research subject

The subject evaluated in this study was a 72-year-old male (height 177.8 cm; weight 81.6 kg) with an acquired traumatic amputation of the index finger at the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) on the left hand (non-dominant) distal to the metacarpal joint (MCP) (Fig. 1). The residual limb of the affected hand was 4.5 cm in length (MCP to PIP) and 7 cm in circumference. The non-affected finger on the right hand (dominant) was 9.5 cm in length and 7 cm in circumference. Prior to the laboratory visit, this participant provided pictures of both the affected and non-affected hands for the remote fitting of the 3D printed finger prosthesis [10]. The subject had acquired the MCP-Driver™ finger prosthesis (NAKED Prosthetics Inc., Olympia, WA USA) and reported that they regularly used the device prior to participating in this study. The local Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Fig. 1Research subject with amputation at the proximal interphalangeal joint of the left hand

Full size image

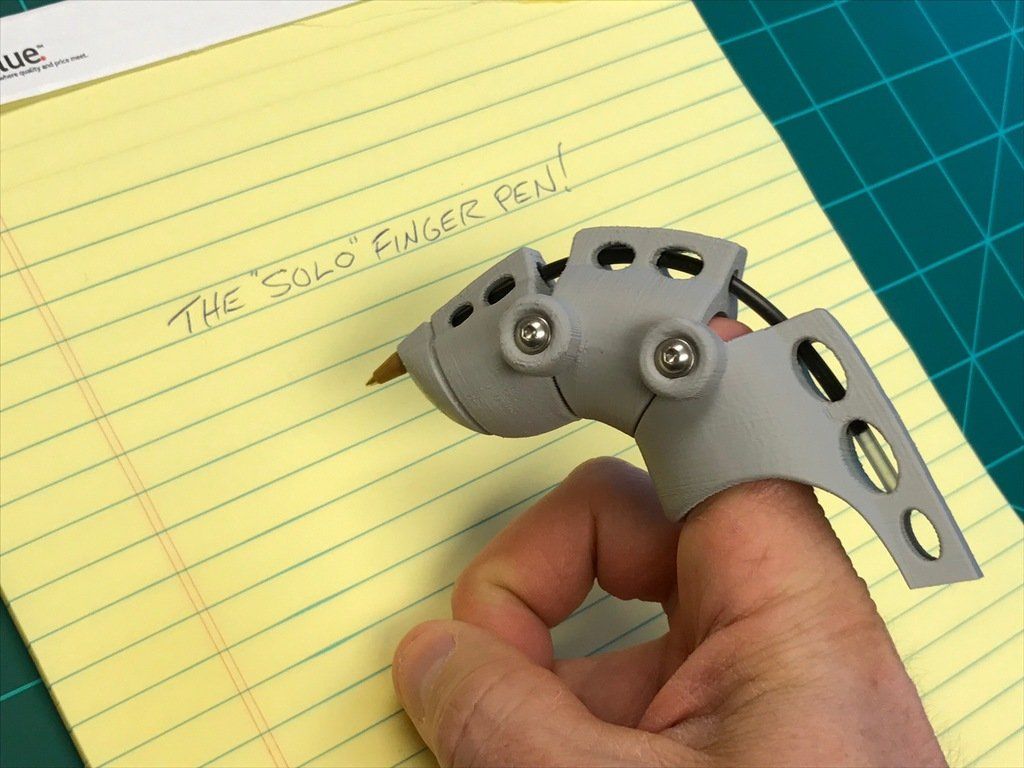

Local 3D printed finger prosthesis

The locally 3D printed finger prosthesis (LPF) was created by the authors for the purpose of testing a prototype of a body-powered partial finger prosthesis. The featured design utilizes a tension-driven voluntary-closing (VC) mechanism, which requires activation of the residual limb’s musculature at the MCP to produce flexion for coordinated manipulation of objects. The prosthesis was designed utilizing the participant’s non-affected finger length, width and circumference to create an approximately sized prosthetic limb to match the non-affected limb. The LPF allows for pinch grasping actions actuated by flexion of the MCP. An MCP flexion angle of 40° produced 1 in. of cable travel for full operation. Drafting and design of this device utilized multiple different methods ranging from parametric design to model sculpting when using a computer-aided design program (CAD) (Autodesk Fusion 360, Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA USA). Overall design of the LFP incorporates three segmented sections with simple pivot joints in-between each segment to provide smooth and coupled movement. These sections include the proximal, middle and distal segments. Joints between the middle and proximal segment allow for movement, however, the joint between the distal and middle segments is frozen with the distal segment of the finger flexed at a 30° angle downward to allow for smoother actuation of the finger when tension is applied by the user.

The featured design utilizes a tension-driven voluntary-closing (VC) mechanism, which requires activation of the residual limb’s musculature at the MCP to produce flexion for coordinated manipulation of objects. The prosthesis was designed utilizing the participant’s non-affected finger length, width and circumference to create an approximately sized prosthetic limb to match the non-affected limb. The LPF allows for pinch grasping actions actuated by flexion of the MCP. An MCP flexion angle of 40° produced 1 in. of cable travel for full operation. Drafting and design of this device utilized multiple different methods ranging from parametric design to model sculpting when using a computer-aided design program (CAD) (Autodesk Fusion 360, Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA USA). Overall design of the LFP incorporates three segmented sections with simple pivot joints in-between each segment to provide smooth and coupled movement. These sections include the proximal, middle and distal segments. Joints between the middle and proximal segment allow for movement, however, the joint between the distal and middle segments is frozen with the distal segment of the finger flexed at a 30° angle downward to allow for smoother actuation of the finger when tension is applied by the user. A rear flat portion is sized to the circumference of the subject’s finger and then thermoformed around the finger during fitting and acts as a retention ring to provide additional stability to the finger. The device was secured using a customized soft neoprene cast fitted to the palm of the hand, which was used to create an anchoring point for actuation of the device to occur and to reduce the amount of friction that the user may experience from the nylon string utilized to produced rotational force around the LFP’s interphalangeal pivot joints. A silicone grip is added onto the fingertip to increase grasp compliance and to prevent slippage of gripped objects. Initial sizing of the prosthesis was performed remotely and began by instructing the patient to photograph both the affected and unaffected limbs including a known measurable scale, such as metric grid paper. This photogrammetric method allowed the extraction of several anthropometric measurements from the photographs, including limb length, width and circumference derived from the limb area.

A rear flat portion is sized to the circumference of the subject’s finger and then thermoformed around the finger during fitting and acts as a retention ring to provide additional stability to the finger. The device was secured using a customized soft neoprene cast fitted to the palm of the hand, which was used to create an anchoring point for actuation of the device to occur and to reduce the amount of friction that the user may experience from the nylon string utilized to produced rotational force around the LFP’s interphalangeal pivot joints. A silicone grip is added onto the fingertip to increase grasp compliance and to prevent slippage of gripped objects. Initial sizing of the prosthesis was performed remotely and began by instructing the patient to photograph both the affected and unaffected limbs including a known measurable scale, such as metric grid paper. This photogrammetric method allowed the extraction of several anthropometric measurements from the photographs, including limb length, width and circumference derived from the limb area. This photograph was then uploaded to a CAD software, which was calibrated by the known unit of measure of the graph paper (i.e. 1 cm boxes) included in the photograph (Fig. 2). Patient anthropometric measures including limb length, width and circumference were utilized to create a socket that was then incorporated into the full design. Once all measure had been validated by a certified prosthetist, STL model files were uploaded to a 3D slicer software (Simplify3D v4.1, Simplify3D, Blue Ashe, OH) to add any material support that would be needed during the printing process. Sliced 3D files were then transferred to a desktop 3D Printer (Ultimaker 2 extended, Ultimaker B.V., Geldermalsen, The Netherlands). The material used in printing the finger prostheses was polylactic acid (PLA). The prosthesis was printed at 35% infill using a rectangular infill pattern, 60 mm/s print speed, 150 mm/s travel speed, 210 °C nozzle temperature, 50 °C heated build plate, 0.15 mm layer height, and 0.8 mm shell thickness.

This photograph was then uploaded to a CAD software, which was calibrated by the known unit of measure of the graph paper (i.e. 1 cm boxes) included in the photograph (Fig. 2). Patient anthropometric measures including limb length, width and circumference were utilized to create a socket that was then incorporated into the full design. Once all measure had been validated by a certified prosthetist, STL model files were uploaded to a 3D slicer software (Simplify3D v4.1, Simplify3D, Blue Ashe, OH) to add any material support that would be needed during the printing process. Sliced 3D files were then transferred to a desktop 3D Printer (Ultimaker 2 extended, Ultimaker B.V., Geldermalsen, The Netherlands). The material used in printing the finger prostheses was polylactic acid (PLA). The prosthesis was printed at 35% infill using a rectangular infill pattern, 60 mm/s print speed, 150 mm/s travel speed, 210 °C nozzle temperature, 50 °C heated build plate, 0.15 mm layer height, and 0.8 mm shell thickness. The design of the LFP allows for all motion components to be printed in place and pre-assembled. Additional components of the finger prosthesis include Nylon string (1 mm diameter) and elastic cord (1.5 mm diameter), which produce the flexion and extension capabilities observed in the functionality of the device. Additional components include medical-grade padded foam as a soft socket and anchoring point and a protective skin sock for the residual limb to reduce friction of the prosthesis on the skin.

The design of the LFP allows for all motion components to be printed in place and pre-assembled. Additional components of the finger prosthesis include Nylon string (1 mm diameter) and elastic cord (1.5 mm diameter), which produce the flexion and extension capabilities observed in the functionality of the device. Additional components include medical-grade padded foam as a soft socket and anchoring point and a protective skin sock for the residual limb to reduce friction of the prosthesis on the skin.

a Rendered CAD model of LFP. b Hand symmetry between the non-affected hand and affected hand with 3D printed finger prosthesis. c Participant performing the Box and Block Test. d Participant typing on an electronic keyboard

Full size image

The LFP was manufactured using PLACTIVE™ (PLACTIVE™ 1% Antibacterial Nanoparticles additive, Copper3D, Santiago, Chile), which is formulated with an internationally patented additive containing copper nanoparticles. Copper nanoparticles have been shown to be effective in eliminating fungi, viruses, and bacteria, but are harmless to humans [15]. PLACTIVE™ was chosen as it uses a sound and proven antibacterial mechanism, is a low-cost material that is biodegradable, and possesses thermoforming characteristics that facilitate post-processing and final adjustments of the LFP. PLACTIVE™ has similar physical (relative viscosity = 4.0 g/dL, clarity = transparent, peak melt temperature = 145–160 °C, glass transition temperature = 55–60 °C) and mechanical (tensile yield strength = 8700 psi, tensile strength at break = 7700 psi, tensile modulus = 524,000 psi, tensile elongation = 6%, flexural strength = 12,000 psi, and heat distortion temperature at 66 psi = 55 °C) properties to standard PLA. The average printing time for the LFP was 60 ± 5.6 min. Post-processing consisted of support removal and filing of rough areas in the joints and prosthetic socket area in contact with the skin. The build orientation on the build platform and generation of the support are illustrated in Fig.

Copper nanoparticles have been shown to be effective in eliminating fungi, viruses, and bacteria, but are harmless to humans [15]. PLACTIVE™ was chosen as it uses a sound and proven antibacterial mechanism, is a low-cost material that is biodegradable, and possesses thermoforming characteristics that facilitate post-processing and final adjustments of the LFP. PLACTIVE™ has similar physical (relative viscosity = 4.0 g/dL, clarity = transparent, peak melt temperature = 145–160 °C, glass transition temperature = 55–60 °C) and mechanical (tensile yield strength = 8700 psi, tensile strength at break = 7700 psi, tensile modulus = 524,000 psi, tensile elongation = 6%, flexural strength = 12,000 psi, and heat distortion temperature at 66 psi = 55 °C) properties to standard PLA. The average printing time for the LFP was 60 ± 5.6 min. Post-processing consisted of support removal and filing of rough areas in the joints and prosthetic socket area in contact with the skin. The build orientation on the build platform and generation of the support are illustrated in Fig. 3. Support was generated for all overhang angles of 45° or higher required support material. The post-processing of the LFP took 10 min, and assembly took 30 min. The total material cost of the LFP was estimated to be $20, due to the multiple prototypes made throughout the development process.

3. Support was generated for all overhang angles of 45° or higher required support material. The post-processing of the LFP took 10 min, and assembly took 30 min. The total material cost of the LFP was estimated to be $20, due to the multiple prototypes made throughout the development process.

Build orientation and support generation of the 3D printed finger prosthesis

Full size image

Commercial finger prosthesis

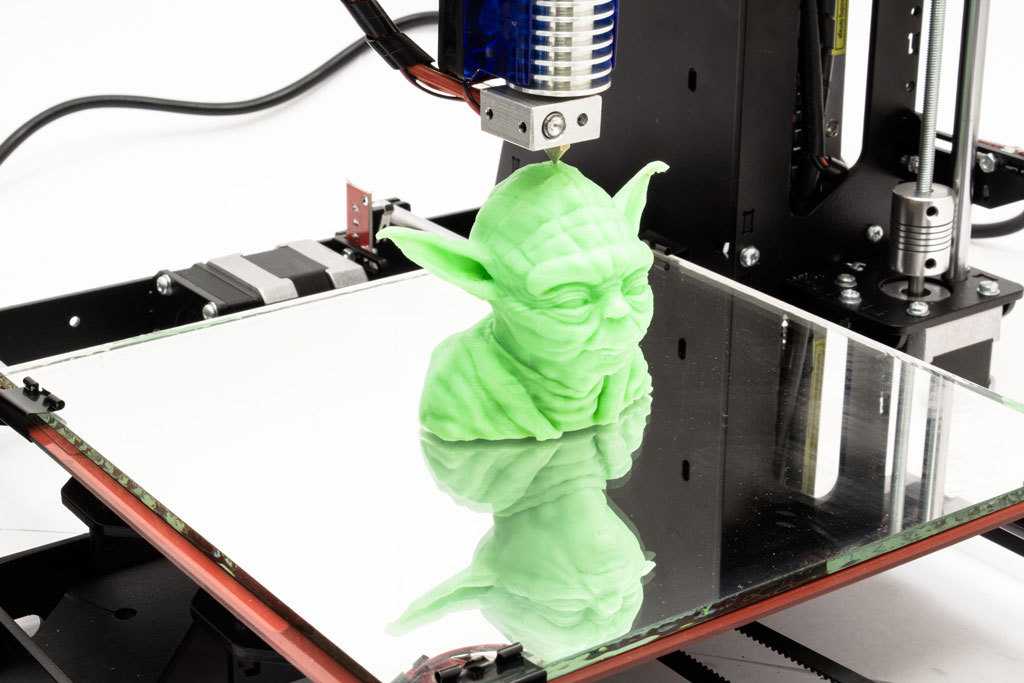

The commercial prosthesis investigated in this study is the MCP-Driver™ (MFP) and is manufactured by NAKED Prosthetics Incorporated. This partial finger prosthesis is body-powered and utilizes a linkage-driven mechanism of action for the articulation of a partial finger amputation. Overall device design specifically accommodates patients that have acquired a proximal phalanx amputation and aims to restore articulation at the middle and distal phalanges. The MFP allows for specific grasping orientations such as pinching, key, and cylindrical types and provides good grip stability. Capabilities of this device include modular force production, as the user is able to modify the amount of force that is directed onto the object that is being grasped allowing for more sensitive objects to be held (i.e., Egg). The MFP is fabricated using titanium, 316 stainless steel, silicone and medical grade nylon, enhancing durability and aesthetic appearance (Fig. 4). The estimated time to fabricate one of these devices is between 6 to 8 weeks, which allows for the collection of proper documentation, photos, and casts from prosthetic practitioners to be received. Multiple MFP devices can be used in the case of multiple amputations at the proximal phalanx, which are anchored to a carbon fiber cast around the palm of the affected hand. The ability to attach multiple prostheses to a centralized anchor-point allows for improved intralimb coordination, force production and overall function of the affected hand. The MFP has the ability for finger adduction and abduction due to articulation at the anchoring point of the cast and can be adjusted by the clinician providing care or the user.

Capabilities of this device include modular force production, as the user is able to modify the amount of force that is directed onto the object that is being grasped allowing for more sensitive objects to be held (i.e., Egg). The MFP is fabricated using titanium, 316 stainless steel, silicone and medical grade nylon, enhancing durability and aesthetic appearance (Fig. 4). The estimated time to fabricate one of these devices is between 6 to 8 weeks, which allows for the collection of proper documentation, photos, and casts from prosthetic practitioners to be received. Multiple MFP devices can be used in the case of multiple amputations at the proximal phalanx, which are anchored to a carbon fiber cast around the palm of the affected hand. The ability to attach multiple prostheses to a centralized anchor-point allows for improved intralimb coordination, force production and overall function of the affected hand. The MFP has the ability for finger adduction and abduction due to articulation at the anchoring point of the cast and can be adjusted by the clinician providing care or the user. Additionally, by increasing the planes of motion that the prosthetic device can move within, the acclimation period to the prosthetic device can be significantly reduced. An adjustable carbon fiber ring is used as a minimal socket to allow for the suspension of the finger. The tensile strength of this ring is 80 lbs. In addition, this simplified socket design improves overall comfort and reduces infringement of the device on range of motion of the fingers [16]. The MFP is available in multiple different aesthetic coatings, which can be selected at the discretion of the user. The MFP is fabricated using a combination of metal 3D printing technology and externally applied components that allow for manual adjustment of the device for a more comfortable fit, which contrasts to the LFP that uses FDM printing and thermoplastics. The cost of this device is estimated to be $9000 to $19,000 per device and highly depends on the parts used for fabrication of the device. In order to obtain accurate information pertaining to this specific device, the authors privately communicated with the manufacturer for more detailed information of specific device discussed in this investigation.

Additionally, by increasing the planes of motion that the prosthetic device can move within, the acclimation period to the prosthetic device can be significantly reduced. An adjustable carbon fiber ring is used as a minimal socket to allow for the suspension of the finger. The tensile strength of this ring is 80 lbs. In addition, this simplified socket design improves overall comfort and reduces infringement of the device on range of motion of the fingers [16]. The MFP is available in multiple different aesthetic coatings, which can be selected at the discretion of the user. The MFP is fabricated using a combination of metal 3D printing technology and externally applied components that allow for manual adjustment of the device for a more comfortable fit, which contrasts to the LFP that uses FDM printing and thermoplastics. The cost of this device is estimated to be $9000 to $19,000 per device and highly depends on the parts used for fabrication of the device. In order to obtain accurate information pertaining to this specific device, the authors privately communicated with the manufacturer for more detailed information of specific device discussed in this investigation.

NAKED Prosthetics Inc. MCP-Driver Finger Prosthesis

Full size image

Procedure

The research subject visited the research laboratory twice, during the first visit an orientation session took place where the testing procedures were fully explained, informed consent was completed and the initial device distributed for use. During the second visit, the subject was given a version of the initial device that was modified for improved comfort, and testing procedures were completed. The Box and Block Test (BBT) was completed, which acts as a functional outcome measure of unilateral gross manual dexterity. The BBT has been used in previous prosthetic assessment studies and has been seen to measure prosthetic limb performance and motor learning [17, 18]. The Box and Block test required the subject to move 1-in. blocks one at a time from one box, over a partition, and to drop the blocks in the adjacent box (Fig. 5). The subject was seated comfortably, and then completed a one-minute trial of the BBT with his affected hand, unaffected hand, and affected hand with the 3D printed prosthesis and MFP The subject was asked to place their hands on the sides of the box. As testing started, the subject was asked to grasp one block at a time, transport the block over the partition, and release it into the opposite compartment.

As testing started, the subject was asked to grasp one block at a time, transport the block over the partition, and release it into the opposite compartment.

Box and Block Test (BBT) and structural dimensions (cm)

Full size image

Two weeks after laboratory testing concluded, the subject was sent a satisfaction survey that utilized two separate prosthetic specific surveys. Prosthesis use and satisfaction were assessed using the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive Technology (QUEST 2.0) [19]. The QUEST 2.0 consists of 12 items with optional satisfaction items that a participant may feel are essential to a particular aspect of their device or service. All responses were graded on a five-point satisfaction scale ranging from one (“not satisfied at all”) to five (“very satisfied”). The QUEST 2.0 utilizes three separate categorization scores including: Device, Service, and average total score of all 12 items based on the range of 1 to 5. The “service” portion did not pertain to this study and therefore the “device” portion of the QUEST was the only one assessed, which encompassed only 8 items. In addition, the Orthotics and Prosthetics Users Survey (OPUS) was used to evaluate the subjects upper extremity functional status and quality of life [20]. The OPUS consists of five subscales; of these, the upper extremity functional status (UEFS) and OPUS-Satisfaction with Devices (CSD) were used, which both use a qualitative rating scale of “Strongly Agree” to “Don’t Know/Not Applicable”. The upper extremity functional status survey consists of 28 questions pertaining to the completion of physical tasks (i.e., Use key in lock, Put on socks). The OPUS – CSD consists of 21 questions that observe the opinion of the user concerning the overall device function and services provided for the device (Table 1). The first 11 questions of the OPUS – CSD were utilized in this study, as the other items lacked in relevance.

The “service” portion did not pertain to this study and therefore the “device” portion of the QUEST was the only one assessed, which encompassed only 8 items. In addition, the Orthotics and Prosthetics Users Survey (OPUS) was used to evaluate the subjects upper extremity functional status and quality of life [20]. The OPUS consists of five subscales; of these, the upper extremity functional status (UEFS) and OPUS-Satisfaction with Devices (CSD) were used, which both use a qualitative rating scale of “Strongly Agree” to “Don’t Know/Not Applicable”. The upper extremity functional status survey consists of 28 questions pertaining to the completion of physical tasks (i.e., Use key in lock, Put on socks). The OPUS – CSD consists of 21 questions that observe the opinion of the user concerning the overall device function and services provided for the device (Table 1). The first 11 questions of the OPUS – CSD were utilized in this study, as the other items lacked in relevance.

Full size table

Results

In the performance of the gross manual dexterity task, the subject moved 18 blocks per minute (BPM) when no prosthesis was utilized. When a prosthesis was used, performance improved to 22 BPM during the one-minute trial with both the LFP and the MFP. Comparatively, the non-affected limb moved 30 BPM, which demonstrates the relative functional difference of the affected limb.

When a prosthesis was used, performance improved to 22 BPM during the one-minute trial with both the LFP and the MFP. Comparatively, the non-affected limb moved 30 BPM, which demonstrates the relative functional difference of the affected limb.

Results of the QUEST 2.0 showed that the LFP scored slightly higher (3.3 ± 1.2), as compared to the MFP (2.5 ± 0.5) device satisfaction. Description of the results for the QUEST 2.0 survey for both the LFP and the MFP are observed (Table 2). Qualitative results for the OPUS – CSD are displayed in Table 1. As only 3 of the 28 questions were completed for the OPUS – UEFS, only completed questions for both prostheses are discussed. The OPUS – UEFS indicated that the participant was able to complete the tasks: “Carry a laundry basket” and “Put on and take off prosthesis” very easily with both prostheses and “Open a bag of chips with both hands” easily with the LFP and very easily with the MFP.

Table 2 Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive Technology (QUEST) RatingsFull size table

Discussion

The primary findings of the current investigation provided evidence that the LFP produced very similar functional results to that of the MFP (Table 3). The results from the current investigation provides evidence demonstrating that both a tension- and linkage- driven body-powered prostheses can produce similar performance outcomes in the BBT. The subject demonstrated a lower functional outcome in the BBT when not using a prosthesis on the affected hand, with 60% task-specific efficiency when compared to the non-affected hand. The use of prostheses improved the task-specific efficiency to 73% of the non-affected hand, suggesting that the use of either the LFP or MFP will improve gross dexterity.

The results from the current investigation provides evidence demonstrating that both a tension- and linkage- driven body-powered prostheses can produce similar performance outcomes in the BBT. The subject demonstrated a lower functional outcome in the BBT when not using a prosthesis on the affected hand, with 60% task-specific efficiency when compared to the non-affected hand. The use of prostheses improved the task-specific efficiency to 73% of the non-affected hand, suggesting that the use of either the LFP or MFP will improve gross dexterity.

Full size table

The current investigation examined the subject’s experienced satisfaction when using both of the prostheses. From the QUEST 2.0 device satisfaction survey, it was observed that the LFP received a slightly higher satisfaction rating, with the most critical satisfaction items being Comfort, Effectiveness, and Adjustments for the LFP, and Comfort, Effectiveness and Weight for the MFP. To supplement the QUEST 2.0 results, the OPUS – CSD provides a qualitative description of the subject’s feelings toward specific aspects of the prosthesis used. The questions used in the OPUS – CSD are similar to those of the QUEST, thus helping to provide more insight into the overall satisfaction with these devices. It can be observed from the OPUS – CSD that the MFP shows no faults in functional or aesthetic aspects, however, may not offer the same affordability or replacement capability as compared to the LFP. In addition, the LFP met the durability standard of the subject in the QUEST but did not meet the standard in the OPUS – CSD; this may indicate such confounding factors as varied survey times, which could lead to a difference in opinion between devices. Lastly, it can be seen that overall comfort was the same across both prostheses, which is important when considering the potentially abrasive surface finish of the additively manufactured parts.

To supplement the QUEST 2.0 results, the OPUS – CSD provides a qualitative description of the subject’s feelings toward specific aspects of the prosthesis used. The questions used in the OPUS – CSD are similar to those of the QUEST, thus helping to provide more insight into the overall satisfaction with these devices. It can be observed from the OPUS – CSD that the MFP shows no faults in functional or aesthetic aspects, however, may not offer the same affordability or replacement capability as compared to the LFP. In addition, the LFP met the durability standard of the subject in the QUEST but did not meet the standard in the OPUS – CSD; this may indicate such confounding factors as varied survey times, which could lead to a difference in opinion between devices. Lastly, it can be seen that overall comfort was the same across both prostheses, which is important when considering the potentially abrasive surface finish of the additively manufactured parts.

From the OPUS – Upper Extremity Functional Status survey it was observed that only 3 of the 28 questions were answered fully, making qualitative comparisons between these prostheses difficult for the current participant. This substantial difference in response type (i.e. Not Applicable or Very Easy) may be due to the limited amount of time that the subject was given to use the LFP. The MFP was shown to have significantly more use due to the substantially higher number of question completion, as compared to the LFP. The vast majority of all tasks were observed to be relative “Easy” or “Very Easy”, with the exceptions of “Twisting a lid off a small bottle” and “peeling potatoes with a knife/peeler”. From the UEFS portion of the OPUS, it can be seen that the MFP is very functional and easy to use and can be used for a broad range of ADLs. In general, each prosthetic device provides different functional implications that individuals may find valuable throughout specific activities in daily life. As adequate qualitative measures could not be obtained for both devices in the current investigation, any implications derived from the qualitative results should be considered finite. Based on the information provided, neither prosthetic can be advocated for over the other; therefore, further information should be collected concerning device satisfaction.

This substantial difference in response type (i.e. Not Applicable or Very Easy) may be due to the limited amount of time that the subject was given to use the LFP. The MFP was shown to have significantly more use due to the substantially higher number of question completion, as compared to the LFP. The vast majority of all tasks were observed to be relative “Easy” or “Very Easy”, with the exceptions of “Twisting a lid off a small bottle” and “peeling potatoes with a knife/peeler”. From the UEFS portion of the OPUS, it can be seen that the MFP is very functional and easy to use and can be used for a broad range of ADLs. In general, each prosthetic device provides different functional implications that individuals may find valuable throughout specific activities in daily life. As adequate qualitative measures could not be obtained for both devices in the current investigation, any implications derived from the qualitative results should be considered finite. Based on the information provided, neither prosthetic can be advocated for over the other; therefore, further information should be collected concerning device satisfaction.

Limitations of the present investigation are related to the number of trials performed during functional testing, a limited number of materials used in fabrication, use of only one testing protocol, and the amount of time the subject used one device compared to another. Specific limitations of the LFP relate to the limited functionality and fitting of the device, as it only provides the ability to flex and extend the artificial appendage, compared to the multiple planes of movement allowed by the commercially available MFP. In addition, the must be thermoformed to the individual’s affected limb, which requires experience fitting a prosthetic device and an understanding of thermoplastic element of the filament used in the fabrication process. Furthermore, a more comprehensive testing protocol should be used when evaluating the overall functionality of a prosthetic device to include benchmark factors such as friction coefficient, compliancy, and cycling tests to ensure the reliability of a specific device over time. As the survey results showed some valuable information, many of the questions were unable to be answered due to inadequate time with a specific prosthesis and therefore a longer period of use should be allowed prior to survey administration.

As the survey results showed some valuable information, many of the questions were unable to be answered due to inadequate time with a specific prosthesis and therefore a longer period of use should be allowed prior to survey administration.

Future prototypes of 3D printed finger prostheses may encompass different mechanisms of action such as myoelectric, tension-, or linkage- driven mechanisms. Future studies should test a larger sample size using different prostheses, each with its own unique mechanism of action. While the primary findings of this case study indicate that a LFP can compare to the functional improvement seen in commercially fabricated prosthesis, the overall quality of life outcomes are not as definitive. It is clear that using a finger prosthesis for amputation at this specific amputation level are beneficial, however, further investigations must be performed to validate the efficacy of using these prostheses for amputations that are either more or less significant than the case displayed in this investigation.

Conclusion

The current investigation described two different types of body-powered finger prostheses and observed the functional and satisfaction outcomes of a single subject. An improvement in function is evident when either prostheses was used, with principal differences between the prostheses being the method of fabrication, design, and overall mechanisms of action. As the accessibility to 3D printing continues to enlarge, there is great potential for 3D printing to pave the way for multiple new medical applications and devices, which may transform the fabrication process of future medical devices.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- BBT:

-

Box and Block Test

- BPM:

-

Blocks per Minute

- CAD:

-

Computer-Aided Design

- CSD:

-

Satisfaction with Devices

- FDM:

-

Fused Deposition Modeling

- LFP:

-

Local 3D Printed Finger Prosthesis

- MCP:

-

Metacarpal Joint

- MFP:

-

MCP-Driver™

- OPUS:

-

Orthotics and Prosthetics Users Survey

- PIP:

-

Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

- PLA:

-

Polylactic Acid

- QUEST:

-

Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology

- STL:

-

Stereolithographic

- UEFS:

-

Upper Extremity Functional Status

References

Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):422–9.

Article Google Scholar

Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Incidence, acute care length of stay, and discharge to rehabilitation of traumatic amputee patients: an epidemiologic study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(3):279–87.

CAS Article Google Scholar

Kuret Z, Burger H, Vidmar G, Maver T. Adjustment to finger amputation and silicone finger prosthesis use. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;0(0):1–6.

Google Scholar

Shirota C, et al. On the assessment of coordination between upper extremities: towards a common language between rehabilitation engineers, clinicians and neuroscientists.

J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13(1):1–14.

J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13(1):1–14.Article Google Scholar

Bosmans J, Geertzen J, Dijkstra PU. Consumer satisfaction with the services of prosthetics and orthotics facilities. Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2009;33(1):69–77.

Article Google Scholar

Jang CH, et al. A survey on activities of daily living and occupations of upper extremity amputees. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35(6):907.

Article Google Scholar

Biddiss E, Chau T. Upper limb prosthesis use and abandonment: a survey of the last 25 years. Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2007;31(3):236–57.

Article Google Scholar

E. Biddiss and T Chau, “Disability and Rehabilitation : Assistive Technology The roles of predisposing characteristics , established need , and enabling resources on upper extremity prosthesis use and abandonment,” vol 3107, 2009.

Routhier F, Vincent C, Morissette MJ, Desaulniers L. Clinical results of an investigation of paediatric upper limb myoelectric prosthesis fitting at the Quebec rehabilitation institute. Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2001;25(2):119–31.

CAS Article Google Scholar

Zuniga J, et al. Cyborg beast: a low-cost 3d-printed prosthetic hand for children with upper-limb differences. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(1).

Article Google Scholar

Ferreira JC, Alves NMF, Bartolo PJS. Rapid manufacturing of medical prostheses. Int J Manuf Technol Manag. 2004;6(6):567–83.

Article Google Scholar

Tay FEH, Manna MA, Liu LX. A CASD/CASM method for prosthetic socket fabrication using the FDM technology. Rapid Prototyp J. 2002;8(4):258–62.

Article Google Scholar

Zuniga JM, et al. Expert review of medical devices remote fitting procedures for upper limb 3d printed prostheses. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2019;0(0):1–10.

Google Scholar

Zuniga JM, Peck J, Srivastava R, Katsavelis D, Carson A. An open source 3D-printed transitional hand prosthesis for children. Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics. 2016;28(3):103–8.

Article Google Scholar

Zuniga J. 3D printed antibacterial prostheses. Appl Sci. 2018;8(9):1651.

Article Google Scholar

Naked Prosthetics, “A robust, custom, functional solution: MCPDriver,” no. 888, pp. 2–4, 2018.

Dromerick AW, Schabowsky CN, Holley RJ, Monroe B, Markotic A, Lum PS.

Effect of training on upper-extremity prosthetic performance and motor learning: a single-case study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(6):1199–204.

Effect of training on upper-extremity prosthetic performance and motor learning: a single-case study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(6):1199–204.Article Google Scholar

Platz T, Pinkowski C, van Wijck F, Kim I-H, di Bella P, Johnson G. Reliability and validity of arm function assessment with standardized guidelines for the Fugl-Meyer test, action research arm test and box and block test: a multicentre study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(4):404–11.

Article Google Scholar

Demers L, Weiss-Lambrou R, Demers L, Ska B. Development of the Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST). Assist Technol. 1996;8(1):3–13.

CAS Article Google Scholar

Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and Prosthetics User’s survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments.

Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191–206.

Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191–206.CAS Article Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our research participant for taking time to participate in this study. In addition, we would like to thank NAKED Prosthetics Inc. for providing technical information of their prosthetic device. Thank you to Copper3D for providing the 3D printing filament PLACTIVE™. Lastly, thank you to our occupational therapist and for fitting the device and all students involved in the 3D Prosthetics and Orthotics Lab for helping in this study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Biomechanics, University of Nebraska at Omaha, 6001 Dodge Street Omaha, Nebraska, NE, 68182, USA

Keaton J.

Young, James E. Pierce & Jorge M. Zuniga

Young, James E. Pierce & Jorge M. ZunigaFacultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Jorge M. Zuniga

Authors

- Keaton J. Young

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- James E. Pierce

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Jorge M. Zuniga

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors listed were actively involved in the conceptual design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, as well as manuscript drafting and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Keaton J. Young.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publications of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Case Study: A 3D Printed Patient Specific Partial Finger Prosthesis - 3DPrint.com

From the University of Nebraska at Omaha, researchers Keaton Young, James E. Pierce, and James M. Zuniga explore prosthetics made via 3D printing in ‘Assessment of body-powered 3D printed partial finger prostheses: a case study.’ Here they learn more about how a hand prosthetic was able to change the quality of life for a 72-year-old man with a partial finger amputation.

Pierce, and James M. Zuniga explore prosthetics made via 3D printing in ‘Assessment of body-powered 3D printed partial finger prostheses: a case study.’ Here they learn more about how a hand prosthetic was able to change the quality of life for a 72-year-old man with a partial finger amputation.

Partial loss in the hand such as that of the fingers is considered to be a ‘minor amputation,’ and the authors state that this is unfortunately common; in fact, by 2050 nearly 3.6 million amputations are expected—affecting individuals and all the many tasks they need to complete daily. Many prosthetics are able to assist greatly in activities of daily living (ADLs), along with improving:

- Psychosocial self-esteem

- Body image

- Interlimb coordination

- Body symmetry

Many devices also result in ‘abandonment’ though as patients experience rejection of the device, pain due to ill fit, frustration due to inferior design, and self-consciousness if they are unhappy with aesthetics. Up to 70 percent of individuals with prosthetics report being unhappy with them. In the case study examined during this research, the individual had lost part of the index finger on his right hand. He had previously been using a titanium MCP-Driver™ finger prosthesis (NAKED Prosthetics Inc., Olympia, WA USA) with some success too—although they could be considered cost-prohibitive by some at $9,000 to $19,000. The titanium device would serve as a comparison for the one created in this study.

Up to 70 percent of individuals with prosthetics report being unhappy with them. In the case study examined during this research, the individual had lost part of the index finger on his right hand. He had previously been using a titanium MCP-Driver™ finger prosthesis (NAKED Prosthetics Inc., Olympia, WA USA) with some success too—although they could be considered cost-prohibitive by some at $9,000 to $19,000. The titanium device would serve as a comparison for the one created in this study.

Research subject with amputation at the proximal interphalangeal joint of the left hand

Fittings began remotely as the debilitated area of the case study patient’s hand was scanned, along with the other non-affected hand—which served as the model for the prosthesis. The 3D printed part allows for pinch grasping—made possible by three segmented sections with simple pivot joints in between each one.

“The device was secured using a customized soft neoprene cast fitted to the palm of the hand, which was used to create an anchoring point for actuation of the device to occur and to reduce the amount of friction that the user may experience from the nylon string utilized to produced rotational force around the LFP’s interphalangeal pivot joints,” explained the authors.

“A silicone grip is added onto the fingertip to increase grasp compliance and to prevent slippage of gripped objects. Initial sizing of the prosthesis was performed remotely and began by instructing the patient to photograph both the affected and unaffected limbs including a known measurable scale, such as metric grid paper.”

a Rendered CAD model of LFP. b Hand symmetry between the non-affected hand and affected hand with 3D printed finger prosthesis. c Participant performing the Box and Block Test. d Participant typing on an electronic keyboard

Parts were printed on an Ultimaker 2 extended, using PLA, including other components like a nylon string and elastic cord responsible for flexion and extension, along with padded form for a ‘soft socket’ and a protective covering to decrease friction.

Results were impressive as the patient was able to move 18 blocks per minute in the gross manual dexterity task without any prosthesis attached. With the prostheses, he could move 22 BPM—while the non-affected limb moved 30 BPM. The locally 3D printed finger prosthesis (LPF) offered similar results to the MFP device, with task-specific efficiency increased up to 73 percent. The researchers stated that this proved either the LFP or the MFP will improve dexterity for the user.

The locally 3D printed finger prosthesis (LPF) offered similar results to the MFP device, with task-specific efficiency increased up to 73 percent. The researchers stated that this proved either the LFP or the MFP will improve dexterity for the user.

“As the accessibility to 3D printing continues to enlarge, there is great potential for 3D printing to pave the way for multiple new medical applications and devices, which may transform the fabrication process of future medical devices,” concluded the researchers.

NAKED Prosthetics Inc. MCP-Driver Finger Prosthesis

To lose functionality of a limb, suffer an amputation, or deal with a congenital defect means you have to work a lot harder than everyone else to do things they take for granted—like walking, running, grasping items, eating, playing a musical instrument, and countless other items. Designers around the world have used the advantages of 3D printing to change the lives of many, from prosthetic legs to walking sticks, devices to assist in outdoor activities, and so much more. Find out more about hand prosthetics here.

Find out more about hand prosthetics here.

What do you think of this news? Let us know your thoughts; join the discussion of this and other 3D printing topics at 3DPrintBoard.com.

Build orientation and support generation of the 3D printed finger prosthesis

[Source / Images: ‘Assessment of body-powered 3D printed partial finger prostheses: a case study]

Stay up-to-date on all the latest news from the 3D printing industry and receive information and offers from third party vendors.

Tagged with: 3d printed prosthetics • pla • ultimaker 2 extended • University of Nebraska at Omaha

Please enable JavaScript to view the comments powered by Disqus.

Affordable SLS 3D printing for custom prosthetics

Partial Hand Solutions is committed to developing new technologies for amputees of all ages. Since its founding in 2007, the company has provided functional solutions for many active duty soldiers and other partially hand and finger amputees, as well as children in need of more complex prosthetics.

Founder Matthew Mikos has been designing custom-made prostheses for a long time, but until recently he was unable to solve one fundamental problem: how to make strong, custom-made prostheses at an affordable price.

For the past two years, Matthew has used third-party injection molding companies to provide prosthetic fingers to people of all ages to improve their mobility and functionality. But every patient is unique, and third-party models are only available in one of five sizes and can be delivered within two weeks.

Founder Matthew Mikos wants to offer patients products that are not currently available to them by providing customized solutions. To achieve this goal, he spent some time studying various technologies, from injection molding devices to stereolithography (SLA) and deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printers. Matthew has always been interested in 3D printing nylon models using selective laser sintering (SLS), but due to their high cost, he was unable to really experiment with it.

Matthew recently had the opportunity to try Formlabs' new Fuse 1 printer with SLS technology, as well as the Fuse Sift post-processing station, which opens up new possibilities for creating custom prostheses at a much more affordable price. “I always wanted to buy a printer with SLS technology, but it was not possible due to its high cost. Fuse 1 is the perfect choice for small businesses like Partial Hand Solutions.”

Download PDF

Would you like to save this article, print it or share it with colleagues? Download it in PDF format.

Download as PDF

Selective Laser Sintering is an additive manufacturing technology that uses a laser to sinter a powdered plastic material into a solid structure based on a 3D model.

Fuse 1 is an affordable industrial grade SLS 3D printer from Formlabs that delivers competitive print quality in a small footprint and easy workflow.

Fuse Sift is a powder recovery station for Fuse 1, which is used to remove models from the working chamber, clean them, sift the green powder and process it.

With Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift, Matthew finally has the ability to create high-performance 3D printed prostheses tailored to the needs of patients. For the first time, it can print light, strong, and durable models at a price that small businesses can afford.

What makes the Fuse 1 SLS 3D printer stand out from other SLS printers that Matthew has used before? Matthew identified two main benefits:

-

An efficient workflow that reduces costs and maximizes design time.

-

High quality models that enable his small business to create unique, durable and customized prostheses.

"Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift work very well together - exactly what you would expect from a tool of this caliber."

Matthew Mikos

Matt's Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift combination

Like many other skilled design professionals, Matthew is methodical in his office layout. Efficient workflows are essential as they reduce wasted time and the likelihood of unsatisfactory results. But most importantly, they allow him to focus on designing, and not on cleaning the models from the remnants of material.

Efficient workflows are essential as they reduce wasted time and the likelihood of unsatisfactory results. But most importantly, they allow him to focus on designing, and not on cleaning the models from the remnants of material.

Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift were designed to work together. Formlabs develops additive manufacturing processes that make industrial-quality 3D printing affordable for businesses of all sizes. The close union of Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift is the result of many years of design and product testing, resulting in the easiest and most efficient SLS printing process on the market.

When creating children's M Finger prostheses, Matthew does the following:

-

Preform file preparation. Matthew has two Form 2 desktop stereolithography printers that he uses to prototype, so he has extensive experience using PreForm preprint software for Formlabs printers. PreForm software was designed with ease of use in mind, and Matthew's previous experience made it even easier: “Even if you've never used a Formlabs printer before, Preform is really easy to set up.

It makes it easy to prepare a file for printing."

It makes it easy to prepare a file for printing." -

Preparing Fuse 1. Powder is added to Fuse 1 and a clean optical cassette is inserted. The Fuse 1 touchscreen displays a built-in print preparation checklist with written and visual step-by-step instructions for each procedure. “I have done the printing process several times and the instructions are no longer needed. After doing just a few printing tasks, I got comfortable with the printer.”

-

Screening powder after printing models. Fuse Sift automatically doses and mixes used and new powder, thereby reducing waste and controlling powder flow. With Nylon 12 Powder, you can create durable, fully functional models with a material renewal rate of 30%. This means that up to 70% of the recovered powder can be used for printing. “Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift are superbly designed. Being able to take models out of the device, take a couple of steps and clean them up in Fuse Sift is amazing.

”

” -

Model painting and assembly. Models can be spray or otherwise painted, varnished, electroplated or otherwise to obtain the desired color, surface quality and properties such as water resistance (special coating) and electrical conductivity (electrolytic coating). Matthew soaks the M Finger prosthetics in a solution of professional paint and warm water, stirring for 10 minutes. Thanks to this, his models acquire a beautiful black surface.

From software to printing and post-processing, Matthew's M Finger prosthesis (high-strength, patient-tailored, controlled prosthetic fingers) allows Matthew to produce high-quality end-use prostheses in-house with a single printer in just a couple of days.

For small businesses, the ability to recycle powder is critical to SLS printing. The Fuse 1 has been designed with meticulous attention to detail. It delivers maximum productivity at the lowest cost per model, with a build platform that allows models to be tightly packed for maximum efficiency in every print run.

Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift ensure trouble-free printing batch after batch.

White Paper

Looking for a 3D printer to create durable, functional models? Download our white paper to learn how selective laser sintering (SLS) technology works and why it is popular in 3D printing for functional prototypes and end-use products.

Download white paper

Matthew was able to completely eliminate third party injection molding services with a single Fuse 1 3D printer. This is partly due to the Fuse 1's ability to print high quality models efficiently.

Matthew noted that the nylon models created with Fuse 1 have four main advantages:

-

Low material cost. Nylon is an affordable material and Fuse 1 is optimized for printing with recycled powder to reduce waste. “Nylon powder seemed expensive to me, but when I calculated the cost of making one model, the cost of prosthetic fingers turned out to be affordable.

”

” -

Advanced design options. The powder supports the patterns during printing so no special support structures are required. This makes it easy to create overhangs, intricate geometries, interconnecting parts, internal channels and other complex details. “Most importantly, thanks to Fuse 1, I was able to expand my ability to design future products. Now I am thinking about how to improve my work and increase the effectiveness of patient care.”

-

High performance and efficiency. Selective Laser Sintering is the fastest additive manufacturing technology for producing functional, durable prototypes and end-use products. Nesting a large number of models while printing maximizes available workspace. “It takes only two days to print a full working platform of printers. Previously, I had to wait weeks for my injection molded models to arrive.”

-

Proven end use materials. The Nylon used to print models on the Fuse 1 is a proven, high quality thermoplastic material.

It has mechanical properties that are comparable to products made using traditional manufacturing methods such as injection molding or expensive SLS devices. “I used to use an HP SLS printer. Models on the Fuse 1 come out as good as the HP printer, if not better.”

It has mechanical properties that are comparable to products made using traditional manufacturing methods such as injection molding or expensive SLS devices. “I used to use an HP SLS printer. Models on the Fuse 1 come out as good as the HP printer, if not better.”

M Fingers are the flagship product of Partial Hand Solutions. Initially, they were developed for soldiers returning from Afghanistan.

By positioning the moving parts with minimal space between them, Matthew can print functional joints with almost no post-processing. Matthew stated: “This will help me reduce assembly time in the future, as these parts will move as intended with minimal play. I'm impressed with the ability to print functional joints. I will never have to outsource this again.” This kind of pre-assembly, in which functional joints can be printed, is only possible with SLS technology. It completely eliminates the post-processing that Matthew used to need when he used the services of third-party companies.

Fuse 1 is compact and doesn't take up much space, but at first Matthew wasn't sure he could print enough models on it. As he placed the models in the working chamber, he realized that the Fuse 1's compact appearance was deceiving. “At first glance, it seemed to me that the working volume of Fuse 1 is too small. But it can accommodate really many models. I can print 160 fingers in two days. It's just amazing."

Matthew never stands still and constantly creates new finger designs to improve his M Finger prostheses. He believes that his own 3D printing using SLS technology has opened up new methods with which he can make amazing prostheses for future patients.

Prosthetic finger attached to sleeve

As above, the Titan finger is attached to a 3D printed sleeve that connects to the patient's body. In addition to fingers, the sleeve allows you to attach other types of prostheses, such as grips. Typically, Matthew used carbon fiber to make the cases, which is expensive and labor intensive.

Now you can create a wide range of sleeves yourself at an affordable price, even taking into account the individual characteristics and needs of patients. But most importantly, compared to carbon fiber models, these sleeves retain their quality and performance, and can be directly provided to patients as end-use products. Matthew noted: “I don't notice layer lines at all on these models printed on Fuse 1. I followed the recommended tolerances and was blown away by the resulting models. The surface quality of the sleeve is exceptional. I was really impressed and pleased with the overall quality of the model. Such models can be used immediately after printing on the printer.

Young patients in need of prostheses often have to settle for models designed for adults. These models may be too heavy for children until they reach the appropriate age.

Matthew designed the elbow and shoulder for a 10 year old boy from Fuse 1 nylon models that provide sliding and back and forth motion once assembled. Despite its size, the shoulder retains the quality you would expect from models printed on Fuse 1 nylon. Considering the size of the model, Matthew found that the shoulder is even easier to clean in the Fuse Sift than the fingers due to fewer small gaps and remaining powder. Although it takes longer to print an elbow than smaller models, Matthew stated, "Given the model's large size, print times are optimal."

Despite its size, the shoulder retains the quality you would expect from models printed on Fuse 1 nylon. Considering the size of the model, Matthew found that the shoulder is even easier to clean in the Fuse Sift than the fingers due to fewer small gaps and remaining powder. Although it takes longer to print an elbow than smaller models, Matthew stated, "Given the model's large size, print times are optimal."

Formlabs is proud to offer the Fuse 1 SLS 3D Printer and Fuse Sift Powder Recovery Station to help businesses of all sizes reduce outsourcing costs and lead times. Manage the entire product development process, from iterations of first concept design to production of ready-to-use, biocompatible, sterilizable, industrial grade Nylon 12 Powder. High-performance 3D printing is finally within reach with the Fuse 1, an affordable SLS 3D printer that is small and easy to work with.

Whether you're printing custom prostheses, medical prototypes or surgical instruments, Fuse 1 makes high quality medical 3D printing affordable, allowing you to create truly personalized products for your patients. The benefits of the Fuse 1 exceeded Matthew's initial expectations, and he ultimately stated, “I really like this equipment. With Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift, everything is easy. Overall, I give Fuse 1 a five out of five."

The benefits of the Fuse 1 exceeded Matthew's initial expectations, and he ultimately stated, “I really like this equipment. With Fuse 1 and Fuse Sift, everything is easy. Overall, I give Fuse 1 a five out of five."

If you'd like to experience the SLS technology for yourself and evaluate the performance of the Fuse 1 printer, contact us and we'll send you a free Nylon 12 Powder sample.

Learn more: Fuse 1

| 3DNews Technologies and IT market. News printers, print servers, scanners, copiers... "Fingerprints" of 3D printers will help... The most interesting in the reviews 22.10.2018 [17:41], Konstantin Khodakovsky As with human fingerprints, each 3D printer leaves its own unique mark on the printed product. This is the conclusion of a new study from the University at Buffalo, which describes what is believed to be the first accurate method for identifying a 3D printer based on the analysis of the printed object. For example, the method the research team has dubbed PrinTracker could eventually help law enforcement and intelligence agencies track the origin of 3D-printed weapons, counterfeit goods and other illegal goods. “3D printing has many great uses, but it is also a dream for counterfeiters. More importantly, it has the potential to create affordable firearms," ," said lead study author Wenyao Xu, assistant professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Buffalo's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. To understand the method, it is useful to know how most 3D printers work. Just like a conventional inkjet printer, the head of 3D printers moves back and forth as it prints. Instead of ink, the nozzle melts the filament (plastic thread), applying it in layers until a three-dimensional object is formed. Each layer of an object contains tiny folds, usually measured in less than a millimeter, called infill patterns. Wenyao Xu To test the PrinTracker technology, the research team created five door keys using 14 conventional 3D printers: a dozen FDM models and four SLA solutions. The researchers then used a scanner to create digital images of each key. They also analyzed the elements of the filling template using their algorithm. As a result, based on a database of "fingerprints" of 14 3D printers, the researchers were able to match the key with the printer in 99. |

Ideally, these patterns should be uniform. However, the printer model type, filament, nozzle size, assembly features, and other factors make their own small changes to the patterns, resulting in an object that does not exactly match the design scheme. For example, a printer is instructed to create an object with half-millimeter fill patterns. But in reality, the sizes of the templates vary by 5-10% compared to the task. Like a human fingerprint, these patterns are unique and repeatable. As a result, with their help, you can find out on which particular 3D printer the model was printed.

Ideally, these patterns should be uniform. However, the printer model type, filament, nozzle size, assembly features, and other factors make their own small changes to the patterns, resulting in an object that does not exactly match the design scheme. For example, a printer is instructed to create an object with half-millimeter fill patterns. But in reality, the sizes of the templates vary by 5-10% compared to the task. Like a human fingerprint, these patterns are unique and repeatable. As a result, with their help, you can find out on which particular 3D printer the model was printed.