Diy robot arm 3d printer

The 10 Coolest DIY 3D Printable Robotic Arm Projects

Exploring 3D printing robotics is easier and cheaper than ever before, so there is no excuse not to give it a go. Having said that, it takes a lot of time and practice to become an expert. While you might not be ready to build a Terminator in your bedroom, 3D printing robotic arms is an excellent starting point for enthusiasts.

Easily programmable, with fewer moving parts and simple functions, robotic arms are an accessible entry-level sector in 3D printing robotics.

That being said, the current state of print-at-home robotics is nothing close to I-Robot. Robotic arms are little more than controllable or programmable pick-and-place tools right now.

But, there is plenty of cutting-edge technology here to whet anyone’s appetite. And many are open source, so anyone can download the files and have a go at printing themselves. They are a fantastic tool for anyone interested in robotics to teach themselves about robotics, and impress your friends.

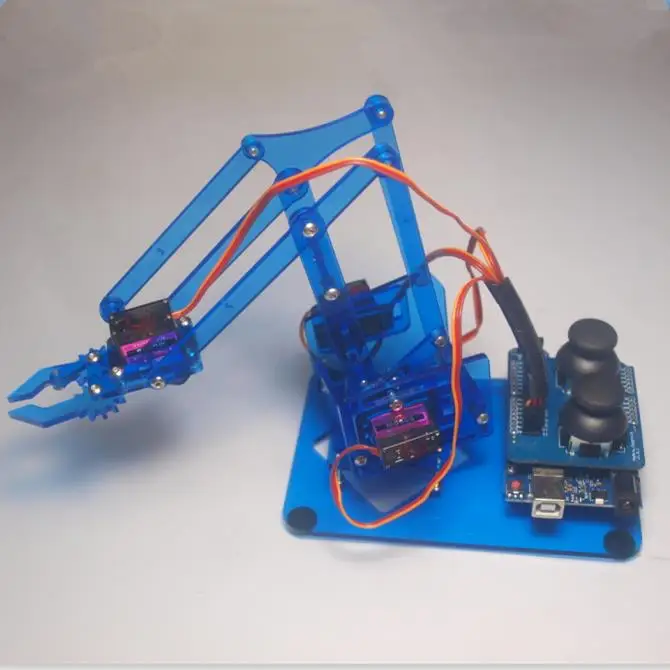

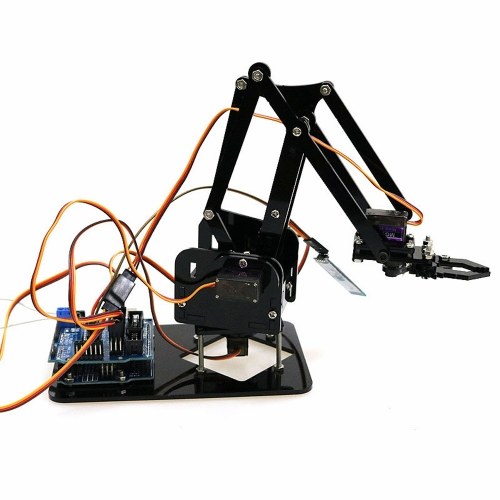

1. LittleArm- The Entry Level

As the name suggests, LittleArm is the smallest, most simplistic, and easiest to print of all the robotic arms on this list. But that does not make it totally useless. Crucially, it is that simplicity that makes it so useful.

Everybody has to start somewhere, especially in 3D printing, and LittleArm is the ideal entry level project to get you hooked on 3D printed robotics. With only 3 degrees of freedom, meaning 3 points of movement on the arm, it is very easy to understand, both when 3D printing and programming.

With little more than a 2C motor and a roll of PLA filament, you can construct the 31 parts needed to build this rugged and flexible arm that can be assembled in less than an hour. Just like David against Goliath, don’t write off the little guy just yet.

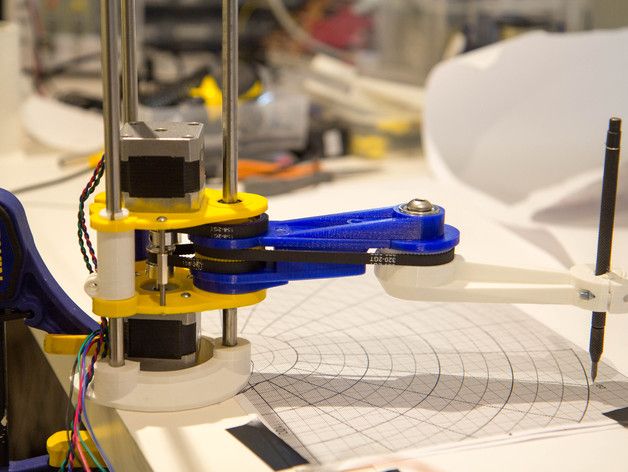

2. EEZYbotARM MK3: The Second Base

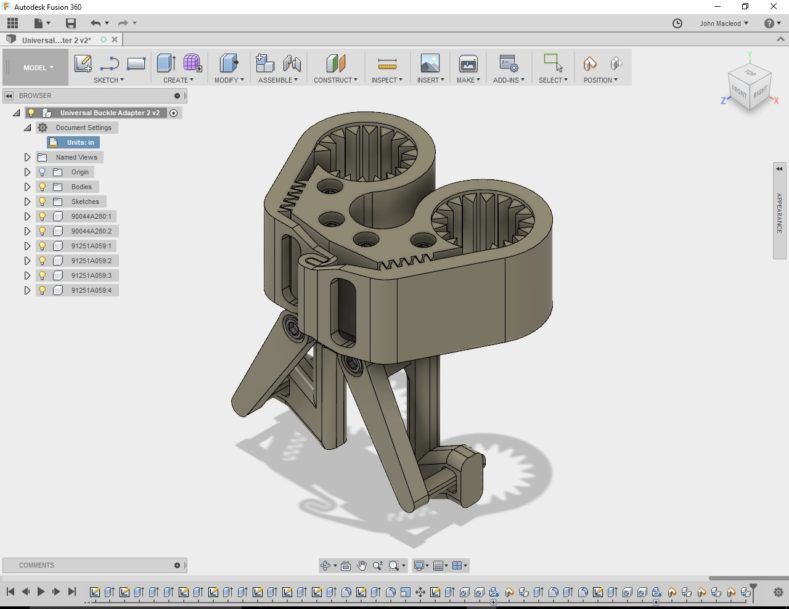

The EEZYbotARM is an ever-evolving 3D printing project that is currently on its third form. Developed by Carlo Franciscone, an engineer from the Novara, Italy, the EEZYbotARM is a slight step up in complexity from LittleArm.

The main enhancement is its 4 directions of freedom, with a rotating base, 2-finger gripper, and a pivot in the arm that allows it to bend. While it doesn’t have the strength to handle a significant payload, it’s definitely a project worth using as an experiment.

The MK3’s design is very similar to its original. The MK2 was created to be a little larger and stronger than its predecessor, but the MK3 returns to the smaller design, with a focus on cheaper motors and construction costs. It was made using ABS, but PLA is also very possible.

If you are looking to try something a little more physically impressive, the MK2 is the clear choice. But when focusing on the accessibility of 3D printable robotic arms, the EEZYbotARM MK3 is your best bet.Image credit: Eezybotarm

3. MeArm: The Everyman 3D Printed Robotic Arm

Hailing from United Kingdom, MeArm is the 3D printed robotic arm project that can cater to anyone. The kits are available to buy on Amazon if you didn’t feel like printing it yourself, but you can also access all the open-source files you need. You can even use a laser cutter if you don’t have a 3D printer to hand.

You can even use a laser cutter if you don’t have a 3D printer to hand.

The MeArm is intended to be easy and fun, with an array of different color schemes. The parts are deliberately simple and easy to fit together. And on top of all that, it comes with a healthy choice of control options for whatever tools you have available.

Want to control the arm using joysticks? MeArm has kits for Arduino and Raspberry Pi, as well as many more. Want to pre-program the arm? There’s a BBC micro:bit kit compatible with Microsoft Make Code. Do you have your own controller you prefer using? You can just get a MeArm without any add-ons. Whatever you need, they have you covered.

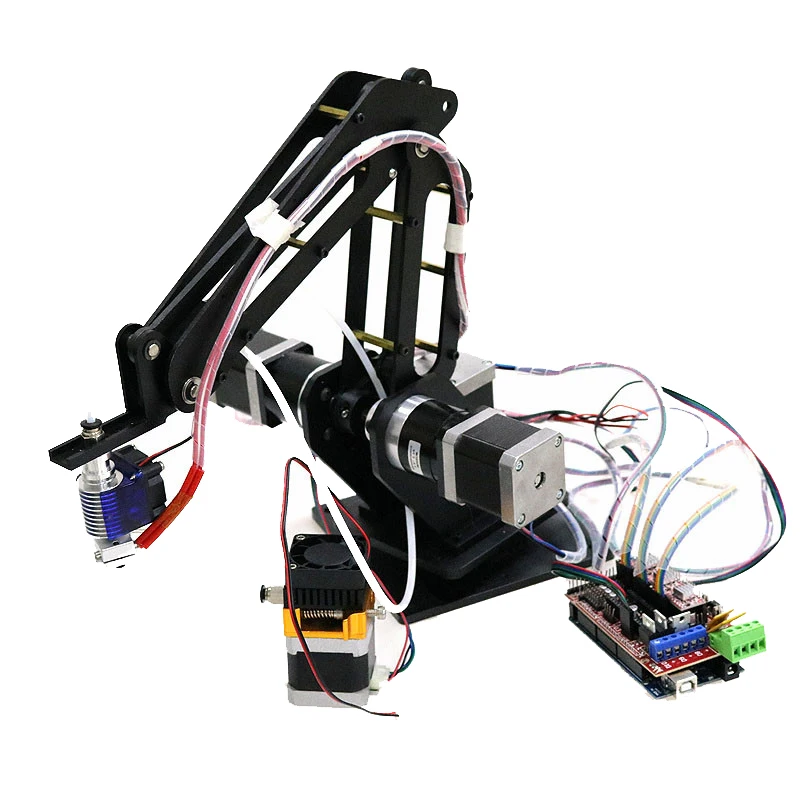

4. Instructables 3D Printed Robot Arm

This is where the scale and intricacy start to rise. The Instructables Workshop has featured lots of amazing 3D printing projects over the years, with a library big enough to have something for everyone. And their 3D printed robot arm is as grand as it is cool.

With circuitry that can be purchased from any good electronics store or wholesaler, the 3D printed arm is a great example of progression for hobbyists or professionals looking to hone their skills. A full list of materials and components, as well as a useful step-by-step guide, can be found on their website.

A full list of materials and components, as well as a useful step-by-step guide, can be found on their website.

Its compact control base makes operation incredibly easy, and all the parts snap together for handy assembly that is surprising fast for an arm of this size. Once you get the basics right, this is the best next step.

5. Kauda Robotic Arm

While a lot of the more advanced 3D printing robotics projects are designed for educational purposes, the Kauda robotic arm is the most widely accessible. Its smaller size means that it is a handy teaching tool for computing students of all ages and abilities.

While Giovanni Lerda’s bulky and more classic design isn’t to everyone’s aesthetic taste, it makes visually understanding the mechanism much easier, vital for younger students. And its small, desktop scale make it an ideal and affordable tool for classrooms across the world.

Computing is fast becoming one of the most important subjects at schools as technology evolves at breakneck pace. Children will increasingly become reliant on education into programming. Few robotics projects on the market today can rival Kauda for ease of access, and it is all made possible by 3D printing.

Children will increasingly become reliant on education into programming. Few robotics projects on the market today can rival Kauda for ease of access, and it is all made possible by 3D printing.

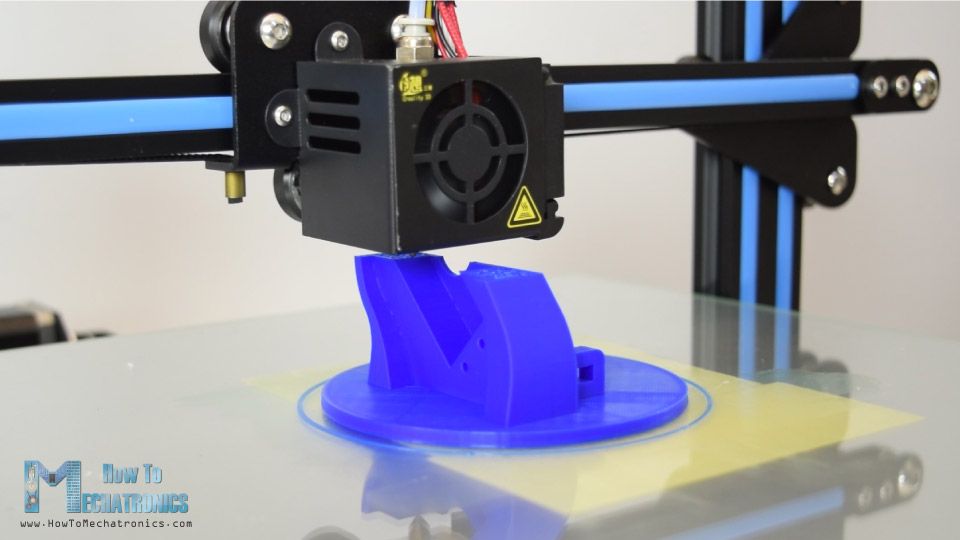

6. How To Mechatronics’ Robotic Arm

A big way to enhance these 3D printed robotic arm projects is to integrate technology that everyone has access to. With that in mind, online engineering site How To Mechatronics have created a controllable 3D printed robotic arm that is operated by a self-designed smartphone app.

The custom android app can be connected via Bluetooth to a node built into the arm, and the user can control the robot using a series of sliders. While the app is not available to download from any store, they do break down how it works and encourage others to recreate its functions and features.

With 3 pivot points, the arm itself is extremely flexible and responsive, making the arm more dexterous and precise. This gives the arm a wider range of industrial applications when the technology becomes more ubiquitous.

And the guide on how to make it is very detailed, walking you through every step carefully. Combining the advanced technology of 3D printed robots with the everyday technology we all have at our disposal is a significant step forward for the industry.

7. Zortrax 3D Printed Robotic Arm

Polish manufacturer Zortrax has developed a 3D printed robotic design with perhaps one of the sleekest and most attractive designs around. It is one to drop anyone’s jaw. The concept art produced looks beautiful, and the files to recreate the design are available to all.

But the Zoftrax 3D printed robotic arm isn’t just a pretty face. It also has a range of useful applications. The design’s 5 degrees of freedom make it as flexible as the best on the market, and the hand at the end is designed to be replaceable with tools like screwdrivers, drills, wrenches, or electromagnets. This makes it a valuable tool for mechanics and construction companies.

The boundless possibilities of this arm through its range of attachable tools make it a very exciting project, and one to keep an eye on as the developers no doubt work on its evolution.

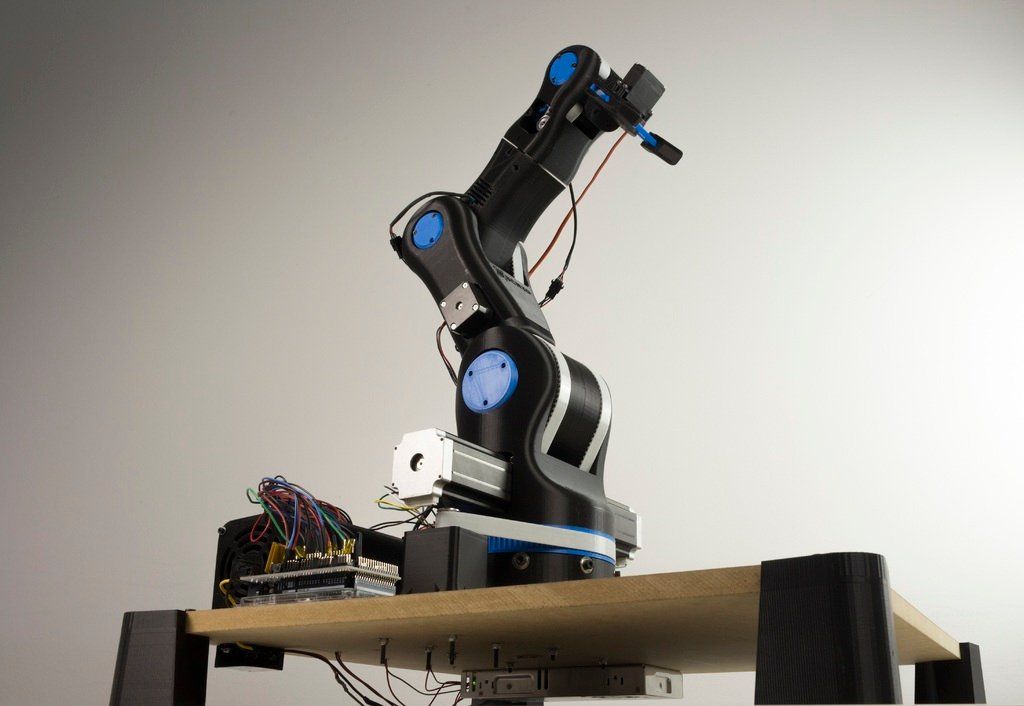

8. Roboteurs RBX1

Technology companies are always looking to go that one step further with their projects. One more turbocharger, one more processor, one more centimeter. It’s no surprise then to see the Roboteurs RBX1, the first 3D printed 6-axis robotic arm.

At this point, there are few practical applications of an arm this complex, other than impressing yourself and anyone else who is interested. But while it may be on the sillier end of the spectrum in that regard, there is a lot here to be excited about.

Roboteurs sell their construction kits online for a modest price considering the level of technology involved. It is one of the only 3D printable robotic arms that require no external machined components, with everything needed provided in the kit.

It is also extremely easy to operate. It is compatible with the most common operating software, and photos provided on their website even feature an Xbox controller! If a 12-year-old Fortnite player could handle this machine, so can you.

9. Haddington Dynamics Robotic Arm

Based in Las Vegas, Nevada, Haddington Dynamics have developed the Mark Henry of 3D printable robot arms. Previous attempts to create a robot arm, affectionately named ‘Dexter,’ using PLA were too weak for HD’s liking. However, after one customer’s advice, and in collaboration with NASA, they began using a Markforged printer.

This allowed them to redesign the robot and begin using carbon fiber, reducing the number of parts from 800 to just 70. The result was a much larger and more robust design with fewer joining points between components that drastically increased its payload weight. The current iteration has a reach of 770mm, and can lift objects as heavy as 3 kilograms.

That might not sound like a lot in the grand scheme of things, but in the world of 3D printed robotic arms, that much weight would put Atlas to shame.Image credit: Markforged.

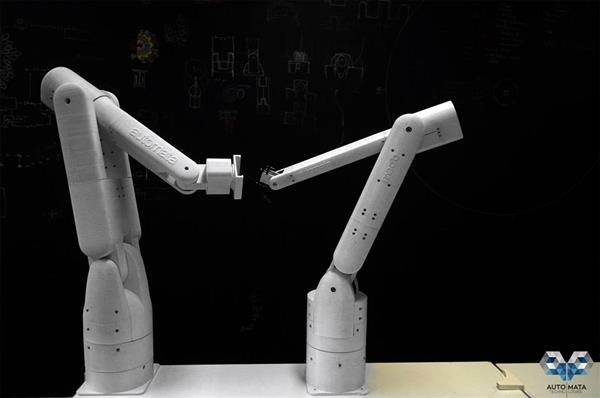

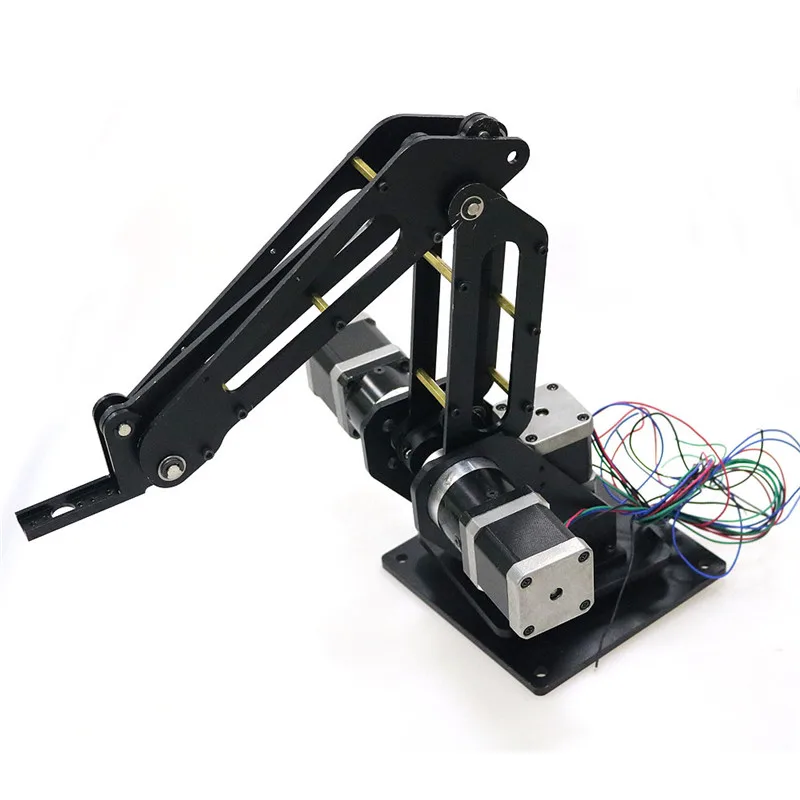

10. BCN3D MOVEO- The King

The BCN3D MOVEO is one of the best and most well-rounded 3D printed robotic arms projects around. The biggest reason is that it incorporates all of the features we’ve mentioned here into one machine.

The biggest reason is that it incorporates all of the features we’ve mentioned here into one machine.

Developed at the Departament d’Ensenyament from the Generalitat de Catalunya in Spain, it was originally designed with education in mind, currently used in 15 different institutes around Catalonia as an educational tool. It has a flexible 5-axis construction with an attractive design, and while it is not capable of extreme weightlifting, it is comparable in function with any of its similar peers.

This pick-and-place device is among the most advanced all-round machines in the industry, with the express purpose of being accessible to anyone. It’ll take a lot of expertise to make your own, but there are few more promising devices around for robotics enthusiasts.

Other fun 3D printing project articles:

- Coolest 3D printer projects

- Beginner 3D printer projects

- 3D printer projects for engineers

- Robotic arm 3D printer projects

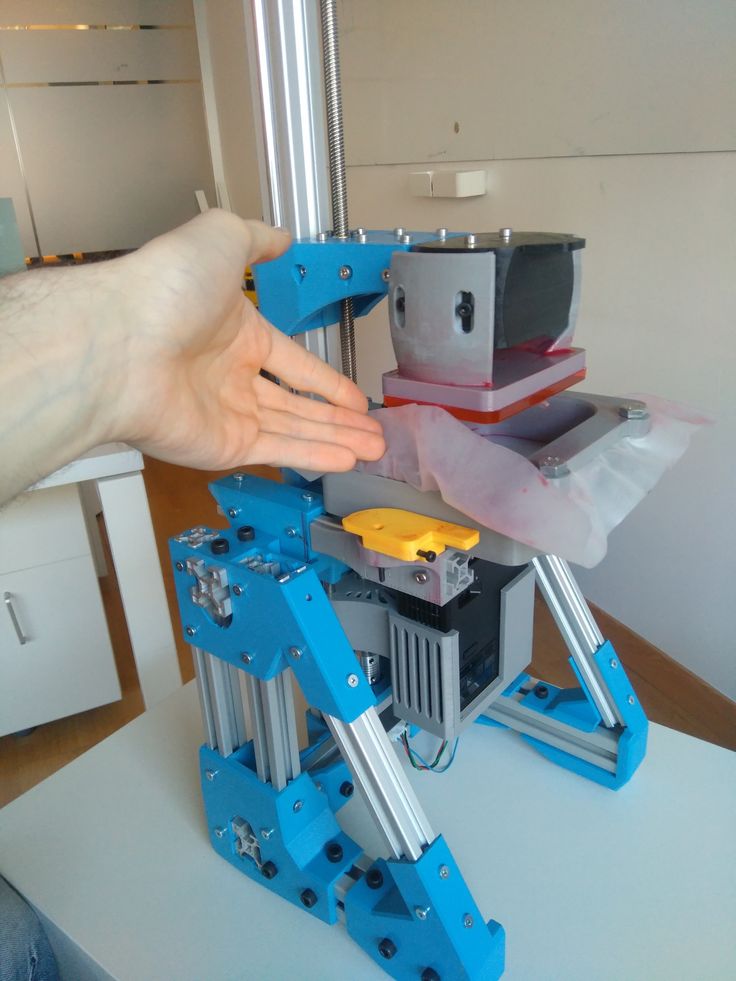

Robot Arm Helps You 3D Print By "Guided Hand"

As Verne understood, the U. S. Civil War (during which 60,000 amputations were performed) inaugurated the modern prosthetics era in the United States, thanks to federal funding and a wave of design patents filed by entrepreneurial prosthetists. The two World Wars solidified the for-profit prosthetics industry in both the United States and Western Europe, and the ongoing War on Terror helped catapult it into a US $6 billion dollar industry across the globe. This recent investment is not, however, a result of a disproportionately large number of amputations in military conflict: Around 1,500 U.S. soldiers and 300 British soldiers lost limbs in Iraq and Afghanistan. Limb loss in the general population dwarfs those figures. In the United States alone, more than 2 million people live with limb loss, with 185,000 people receiving amputations every year. A much smaller subset—between 1,500 to 4,500 children each year—are born with limb differences or absences, myself included.

S. Civil War (during which 60,000 amputations were performed) inaugurated the modern prosthetics era in the United States, thanks to federal funding and a wave of design patents filed by entrepreneurial prosthetists. The two World Wars solidified the for-profit prosthetics industry in both the United States and Western Europe, and the ongoing War on Terror helped catapult it into a US $6 billion dollar industry across the globe. This recent investment is not, however, a result of a disproportionately large number of amputations in military conflict: Around 1,500 U.S. soldiers and 300 British soldiers lost limbs in Iraq and Afghanistan. Limb loss in the general population dwarfs those figures. In the United States alone, more than 2 million people live with limb loss, with 185,000 people receiving amputations every year. A much smaller subset—between 1,500 to 4,500 children each year—are born with limb differences or absences, myself included.

Today, the people who design prostheses tend to be well-intentioned engineers rather than amputees themselves. The fleshy stumps of the world act as repositories for these designers’ dreams of a high-tech, superhuman future. I know this because throughout my life I have been fitted with some of the most cutting-edge prosthetic devices on the market. After being born missing my left forearm, I was one of the first cohorts of infants in the United States to be fitted with a myoelectric prosthetic hand, an electronic device controlled by the wearer’s muscles tensing against sensors inside the prosthetic socket. Since then, I have donned a variety of prosthetic hands, each of them striving toward perfect fidelity of the human hand—sometimes at a cost of aesthetics, sometimes a cost of functionality, but always designed to mimic and replace what was missing.

The fleshy stumps of the world act as repositories for these designers’ dreams of a high-tech, superhuman future. I know this because throughout my life I have been fitted with some of the most cutting-edge prosthetic devices on the market. After being born missing my left forearm, I was one of the first cohorts of infants in the United States to be fitted with a myoelectric prosthetic hand, an electronic device controlled by the wearer’s muscles tensing against sensors inside the prosthetic socket. Since then, I have donned a variety of prosthetic hands, each of them striving toward perfect fidelity of the human hand—sometimes at a cost of aesthetics, sometimes a cost of functionality, but always designed to mimic and replace what was missing.

In my lifetime, myoelectric hands have evolved from clawlike constructs to multigrip, programmable, anatomically accurate facsimiles of the human hand, most costing tens of thousands of dollars. Reporters can’t get enough of these sophisticated, multigrasping “bionic” hands with lifelike silicone skins and organic movements, the unspoken promise being that disability will soon vanish and any lost limb or organ will be replaced with an equally capable replica. Prosthetic-hand innovation is treated like a high-stakes competition to see what is technologically possible. Tyler Hayes, CEO of the prosthetics startup Atom Limbs, put it this way in a WeFunder video that helped raise $7.2 million from investors: “Every moonshot in history has started with a fair amount of crazy in it, from electricity to space travel, and Atom Limbs is no different.”

Prosthetic-hand innovation is treated like a high-stakes competition to see what is technologically possible. Tyler Hayes, CEO of the prosthetics startup Atom Limbs, put it this way in a WeFunder video that helped raise $7.2 million from investors: “Every moonshot in history has started with a fair amount of crazy in it, from electricity to space travel, and Atom Limbs is no different.”

We are caught in a bionic-hand arms race. But are we making real progress? It’s time to ask who prostheses are really for, and what we hope they will actually accomplish. Each new multigrasping bionic hand tends to be more sophisticated but also more expensive than the last and less likely to be covered (even in part) by insurance. And as recent research concludes, much simpler and far less expensive prosthetic devices can perform many tasks equally well, and the fancy bionic hands, despite all of their electronic options, are rarely used for grasping.

Activity arms, such as this one manufactured by prosthetics firm Arm Dynamics, are less expensive and more durable than bionic prostheses. The attachment from prosthetic-device company Texas Assistive Devices rated for very heavy weights, allowing the author to perform exercises that would be risky or impossible with her much more expensive bebionic arm.Gabriela Hasbun; Makeup: Maria Nguyen for MAC cosmetics; Hair: Joan Laqui for Living Proof

Function or Form

In recent decades, the overwhelming focus of research into and development of new artificial hands has been on perfecting different types of grasps. Many of the most expensive hands on the market differentiate themselves by the number and variety of selectable prehensile grips. My own media darling of a hand, the bebionic from Ottobock, which I received in 2018, has a fist-shaped power grip, pinching grips, and one very specific mode with thumb on top of index finger for politely handing over a credit card. My 21st-century myoelectric hand seemed remarkable—until I tried using it for some routine tasks, where it proved to be more cumbersome and time consuming than if I had simply left it on the couch. I couldn’t use it to pull a door shut, for example, a task I can do with my stump. And without the extremely expensive addition of a powered wrist, I couldn’t pour oatmeal from a pot into a bowl. Performing tasks the cool bionic way, even though it mimicked having two hands, wasn’t obviously better than doing things my way, sometimes with the help of my legs and feet.

My 21st-century myoelectric hand seemed remarkable—until I tried using it for some routine tasks, where it proved to be more cumbersome and time consuming than if I had simply left it on the couch. I couldn’t use it to pull a door shut, for example, a task I can do with my stump. And without the extremely expensive addition of a powered wrist, I couldn’t pour oatmeal from a pot into a bowl. Performing tasks the cool bionic way, even though it mimicked having two hands, wasn’t obviously better than doing things my way, sometimes with the help of my legs and feet.

When I first spoke with Ad Spiers, lecturer in robotics and machine learning at Imperial College London, it was late at night in his office, but he was still animated about robotic hands—the current focus of his research. Spiers says the anthropomorphic robotic hand is inescapable, from the reality of today’s prosthetics to the fantasy of sci-fi and anime. “In one of my first lectures here, I showed clips of movies and cartoons and how cool filmmakers make robot hands look,” Spiers says. “In the anime Gundam, there are so many close-ups of gigantic robot hands grabbing things like massive guns. But why does it need to be a human hand? Why doesn’t the robot just have a gun for a hand?”

“In the anime Gundam, there are so many close-ups of gigantic robot hands grabbing things like massive guns. But why does it need to be a human hand? Why doesn’t the robot just have a gun for a hand?”

It’s time to ask who prostheses are really for, and what we hope they will actually accomplish.

Spiers believes that prosthetic developers are too caught up in form over function. But he has talked to enough of them to know they don’t share his point of view: “I get the feeling that people love the idea of humans being great, and that hands are what make humans quite unique.” Nearly every university robotics department Spiers visits has an anthropomorphic robot hand in development. “This is what the future looks like,” he says, and he sounds a little exasperated. “But there are often better ways.”

The vast majority of people who use a prosthetic limb are unilateral amputees—people with amputations that affect only one side of the body—and they virtually always use their dominant “fleshy” hand for delicate tasks such as picking up a cup. Both unilateral and bilateral amputees also get help from their torsos, their feet, and other objects in their environment; rarely are tasks performed by a prosthesis alone. And yet, the common clinical evaluations to determine the success of a prosthetic are based on using only the prosthetic, without the help of other body parts. Such evaluations seem designed to demonstrate what the prosthetic hand can do rather than to determine how useful it actually is in the daily life of its user. Disabled people are still not the arbiters of prosthetic standards; we are still not at the heart of design.

Both unilateral and bilateral amputees also get help from their torsos, their feet, and other objects in their environment; rarely are tasks performed by a prosthesis alone. And yet, the common clinical evaluations to determine the success of a prosthetic are based on using only the prosthetic, without the help of other body parts. Such evaluations seem designed to demonstrate what the prosthetic hand can do rather than to determine how useful it actually is in the daily life of its user. Disabled people are still not the arbiters of prosthetic standards; we are still not at the heart of design.

The Hosmer Hook [left], originally designed in 1920, is the terminal device on a body-powered design that is still used today. A hammer attachment [right] may be more effective than a gripping attachment when hammering nails into wood.Left: John Prieto/The Denver Post/Getty Images; Right: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

Prosthetics in the Real World

To find out how prosthetic users live with their devices, Spiers led a study that used cameras worn on participants’ heads to record the daily actions of eight people with unilateral amputations or congenital limb differences. The study, published last year in IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics, included several varieties of myoelectric hands as well as body-powered systems, which use movements of the shoulder, chest, and upper arm transferred through a cable to mechanically operate a gripper at the end of a prosthesis. The research was conducted while Spiers was a research scientist at Yale University’s GRAB Lab, headed by Aaron Dollar. In addition to Dollar, he worked closely with grad student Jillian Cochran, who coauthored the study.

The study, published last year in IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics, included several varieties of myoelectric hands as well as body-powered systems, which use movements of the shoulder, chest, and upper arm transferred through a cable to mechanically operate a gripper at the end of a prosthesis. The research was conducted while Spiers was a research scientist at Yale University’s GRAB Lab, headed by Aaron Dollar. In addition to Dollar, he worked closely with grad student Jillian Cochran, who coauthored the study.

Watching raw footage from the study, I felt both sadness and camaraderie with the anonymous prosthesis users. The clips show the clumsiness, miscalculations, and accidental drops that are familiar to even very experienced prosthetic-hand users. Often, the prosthesis simply helps brace an object against the body to be handled by the other hand. Also apparent was how much time people spent preparing their myoelectric prostheses to carry out a task—it frequently took several extra seconds to manually or electronically rotate the wrists of their devices, line up the object to grab it just right, and work out the grip approach. The participant who hung a bottle of disinfectant spray on their “hook” hand while wiping down a kitchen counter seemed to be the one who had it all figured out.

The participant who hung a bottle of disinfectant spray on their “hook” hand while wiping down a kitchen counter seemed to be the one who had it all figured out.

In the study, prosthetic devices were used on average for only 19 percent of all recorded manipulations. In general, prostheses were employed in mostly nonprehensile actions, with the other, “intact” hand doing most of the grasping. The study highlighted big differences in usage between those with nonelectric, body-powered prosthetics and those with myoelectric prosthetics. For body-powered prosthetic users whose amputation was below the elbow, nearly 80 percent of prosthesis usage was nongrasping movement—pushing, pressing, pulling, hanging, and stabilizing. For myoelectric users, the device was used for grasping just 40 percent of the time.

More tellingly, body-powered users with nonelectric grippers or split hooks spent significantly less time performing tasks than did users with more complex prosthetic devices. Spiers and his team noted the fluidity and speed with which the former went about doing tasks in their homes. They were able to use their artificial hands almost instantaneously and even experience direct haptic feedback through the cable that drives such systems. The research also revealed little difference in use between myoelectric single-grasp devices and fancier myoelectric multiarticulated, multigrasp hands—except that users tended to avoid hanging objects from their multigrasp hands, seemingly out of fear of breaking them.

Spiers and his team noted the fluidity and speed with which the former went about doing tasks in their homes. They were able to use their artificial hands almost instantaneously and even experience direct haptic feedback through the cable that drives such systems. The research also revealed little difference in use between myoelectric single-grasp devices and fancier myoelectric multiarticulated, multigrasp hands—except that users tended to avoid hanging objects from their multigrasp hands, seemingly out of fear of breaking them.

“We got the feeling that people with multigrasp myoelectric hands were quite tentative about their use,” says Spiers. It’s no wonder, since most myoelectric hands are priced over $20,000, are rarely approved by insurance, require frequent professional support to change grip patterns and other settings, and have costly and protracted repair processes. As prosthetic technologies become more complex and proprietary, the long-term serviceability is an increasing concern. Ideally, the device should be easily fixable by the user. And yet some prosthetic startups are pitching a subscription model, in which users continue to pay for access to repairs and support.

Ideally, the device should be easily fixable by the user. And yet some prosthetic startups are pitching a subscription model, in which users continue to pay for access to repairs and support.

Despite the conclusions of his study, Spiers says the vast majority of prosthetics R&D remains focused on refining the grasping modes of expensive, high-tech bionic hands. Even beyond prosthetics, he says, manipulation studies in nonhuman primate research and robotics are overwhelmingly concerned with grasping: “Anything that isn’t grasping is just thrown away.”

TRS makes a wide variety of body-powered prosthetic attachments for different hobbies and sports. Each attachment is specialized for a particular task, and they can be easily swapped for a variety of activities. Fillauer TRS

Grasping at History

If we’ve decided that what makes us human is our hands, and what makes the hand unique is its ability to grasp, then the only prosthetic blueprint we have is the one attached to most people’s wrists. Yet the pursuit of the ultimate five-digit grasp isn’t necessarily the logical next step. In fact, history suggests that people haven’t always been fixated on perfectly re-creating the human hand.

Yet the pursuit of the ultimate five-digit grasp isn’t necessarily the logical next step. In fact, history suggests that people haven’t always been fixated on perfectly re-creating the human hand.

As recounted in the 2001 essay collection Writing on Hands: Memory and Knowledge in Early Modern Europe, ideas about the hand evolved over the centuries. “The soul is like the hand; for the hand is the instrument of instruments,” Aristotle wrote in De Anima. He reasoned that humanity was deliberately endowed with the agile and prehensile hand because only our uniquely intelligent brains could make use of it—not as a mere utensil but a tool for apprehensio, or “grasping,” the world, literally and figuratively.

More than 1,000 years later, Aristotle’s ideas resonated with artists and thinkers of the Renaissance. For Leonardo da Vinci, the hand was the brain’s mediator with the world, and he went to exceptional lengths in his dissections and illustrations of the human hand to understand its principal components. His meticulous studies of the tendons and muscles of the forearm and hand led him to conclude that “although human ingenuity makes various inventions…it will never discover inventions more beautiful, more fitting or more direct than nature, because in her inventions nothing is lacking and nothing is superfluous.”

His meticulous studies of the tendons and muscles of the forearm and hand led him to conclude that “although human ingenuity makes various inventions…it will never discover inventions more beautiful, more fitting or more direct than nature, because in her inventions nothing is lacking and nothing is superfluous.”

Da Vinci’s illustrations precipitated a wave of interest in human anatomy. Yet for all of the studious rendering of the human hand by European masters, the hand was regarded more as an inspiration than as an object to be replicated by mere mortals. In fact, it was widely accepted that the intricacies of the human hand evidenced divine design. No machine, declared the Christian philosopher William Paley, is “more artificial, or more evidently so” than the flexors of the hand, suggesting deliberate design by God.

Performing tasks the cool bionic way, even though it mimicked having two hands, wasn’t obviously better than doing things my way, sometimes with the help of my legs and feet.

By the mid-1700s, with the Industrial Revolution in the global north, a more mechanistic view of the world began to emerge, and the line between living things and machines began to blur. In her 2003 article “ Eighteenth-Century Wetware,” Jessica Riskin, professor of history at Stanford University, writes, “The period between the 1730s and the 1790s was one of simulation, in which mechanicians tried earnestly to collapse the gap between animate and artificial machinery.” This period saw significant changes in the design of prosthetic limbs. While mechanical prostheses of the 16th century were weighed down with iron and springs, a 1732 body-powered prosthesis used a pulley system to flex a hand made of lightweight copper. By the late 18th century, metal was being replaced with leather, parchment, and cork—softer materials that mimicked the stuff of life.

The techno-optimism of the early 20th century brought about another change in prosthetic design, says Wolf Schweitzer, a forensic pathologist at the Zurich Institute of Forensic Medicine and an amputee. He owns a wide variety of contemporary prosthetic arms and has the necessary experience to test them. He notes that anatomically correct prosthetic hands have been carved and forged for the better part of 2,000 years. And yet, he says, the 20th century’s body-powered split hook is “more modern,” its design more willing to break the mold of the human hand.

He owns a wide variety of contemporary prosthetic arms and has the necessary experience to test them. He notes that anatomically correct prosthetic hands have been carved and forged for the better part of 2,000 years. And yet, he says, the 20th century’s body-powered split hook is “more modern,” its design more willing to break the mold of the human hand.

“The body powered arm—in terms of its symbolism—(still) expresses the man-machine symbolism of an industrial society of the 1920s,” writes Schweitzer in his prosthetic arm blog, “when man was to function as clockwork cogwheel on production lines or in agriculture.” In the original 1920s design of the Hosmer Hook, a loop inside the hook was placed just for tying shoes and another just for holding cigarettes. Those designs, Ad Spiers told me, were “incredibly functional, function over form. All pieces served a specific purpose.”

Schweitzer believes that as the need for manual labor decreased over the 20th century, prostheses that were high-functioning but not naturalistic were eclipsed by a new high-tech vision of the future: “bionic” hands. In 2006, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency launched Revolutionizing Prosthetics, a research initiative to develop the next generation of prosthetic arms with “near-natural” control. The $100 million program produced two multi-articulating prosthetic arms (one for research and another that costs over $50,000). More importantly, it influenced the creation of other similar prosthetics, establishing the bionic hand—as the military imagined it—as the holy grail in prosthetics. Today, the multigrasp bionic hand is hegemonic, a symbol of cyborg wholeness.

In 2006, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency launched Revolutionizing Prosthetics, a research initiative to develop the next generation of prosthetic arms with “near-natural” control. The $100 million program produced two multi-articulating prosthetic arms (one for research and another that costs over $50,000). More importantly, it influenced the creation of other similar prosthetics, establishing the bionic hand—as the military imagined it—as the holy grail in prosthetics. Today, the multigrasp bionic hand is hegemonic, a symbol of cyborg wholeness.

And yet some prosthetic developers are pursuing a different vision. TRS, based in Boulder, Colo., is one of the few manufacturers of activity-specific prosthetic attachments, which are often more durable and more financially accessible than robotic prosthetics. These plastic and silicone attachments, which include a squishy mushroom-shaped device for push-ups, a ratcheting clamp for lifting heavy weights, and a concave fin for swimming, have helped me experience the greatest functionality I have ever gotten out of a prosthetic arm.

Such low-tech activity prostheses and body-powered prostheses perform astonishingly well, for a tiny fraction of the cost of bionic hands. They don’t look or act like human hands, and they function all the better for it. According to Schweitzer, body-powered prostheses are regularly dismissed by engineers as “arcane” or derisively called “Captain Hook.” Future bionic shoulders and elbows may make a huge difference in the lives of people missing a limb up to their shoulder, assuming those devices can be made robust and affordable. But for Schweitzer and a large percentage of users dissatisfied with their myoelectric prosthesis, the prosthetic industry has yet to provide anything fundamentally better or cheaper than body-powered prostheses.

The Breakthroughs We Want

Bionic hands seek to make disabled people “whole,” to have us participate in a world that is culturally two-handed. But it’s more important that we get to live the lives we want, with access to the tools we need, than it is to make us look like everyone else. While many limb-different people have used bionic hands to interact with the world and express themselves, the centuries-long effort to perfect the bionic hand rarely centers on our lived experiences and what we want to do in our lives.

While many limb-different people have used bionic hands to interact with the world and express themselves, the centuries-long effort to perfect the bionic hand rarely centers on our lived experiences and what we want to do in our lives.

We’ve been promised a breakthrough in prosthetic technology for the better part of 100 years now. I’m reminded of the scientific excitement around lab-grown meat, which seems simultaneously like an explosive shift and a sign of intellectual capitulation, in which political and cultural change is passed over in favor of a technological fix. With the cast of characters in the world of prosthetics—doctors, insurance companies, engineers, prosthetists, and the military—playing the same roles they have for decades, it’s nearly impossible to produce something truly revolutionary.

In the meantime, this metaphorical race to the moon is a mission that has forgotten its original concern: helping disabled people acquire and use the tools they want. There are inexpensive, accessible, low-tech prosthetics that are available right now and that need investments in innovation to further bring down costs and improve functionality. And in the United States at least, there is a broken insurance system that needs fixing. Releasing ourselves from the bionic-hand arms race can open up the possibilities of more functional designs that are more useful and affordable, and might help us bring our prosthetic aspirations back down to earth.

There are inexpensive, accessible, low-tech prosthetics that are available right now and that need investments in innovation to further bring down costs and improve functionality. And in the United States at least, there is a broken insurance system that needs fixing. Releasing ourselves from the bionic-hand arms race can open up the possibilities of more functional designs that are more useful and affordable, and might help us bring our prosthetic aspirations back down to earth.

This article appears in the October 2022 print issue.

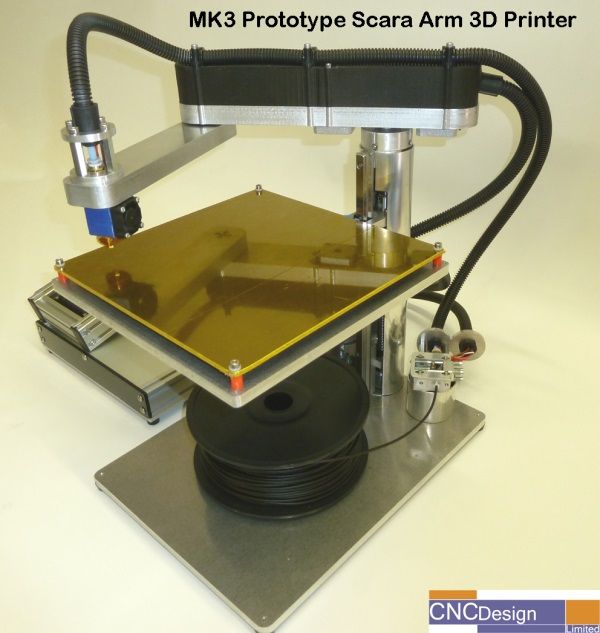

Top 10 DIY 3D Printing Manipulators

3DPrintStory Reviews 10 Best DIY 3D Printing Manipulators

There are many different configurations of robotic arms, but most of them work on the same general principles of movement. Unlike mechanisms that work in the Cartesian coordinate system, such as, for example, 3D printers, manipulators mostly use the polar coordinate system for movement and have an arc-shaped work area. Robotic arms are unique in that they are not limited by footprint and take up very little space compared to other machines with similar features.

Unlike mechanisms that work in the Cartesian coordinate system, such as, for example, 3D printers, manipulators mostly use the polar coordinate system for movement and have an arc-shaped work area. Robotic arms are unique in that they are not limited by footprint and take up very little space compared to other machines with similar features.

In robotics there is such a definition as degrees of freedom (DOF). The term is used to refer to the number of rotating joints or axles on a particular arm, for example a 4DOF arm can be rotated by four separate joints.

Robotic arms are used in a variety of ways, but most are capable of picking up and moving, while some are designed to work in tandem with CNC machines, laser engraving, and even 3D printing.

Because there are hundreds of great designs and designs to consider when choosing a good arm to buy or 3D print, we've narrowed it down to 10 of the best and most popular arms that you can find and reproduce designs using your 3D printer as well. .

.

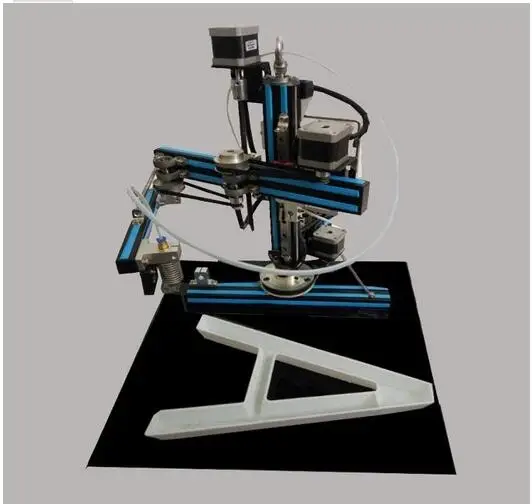

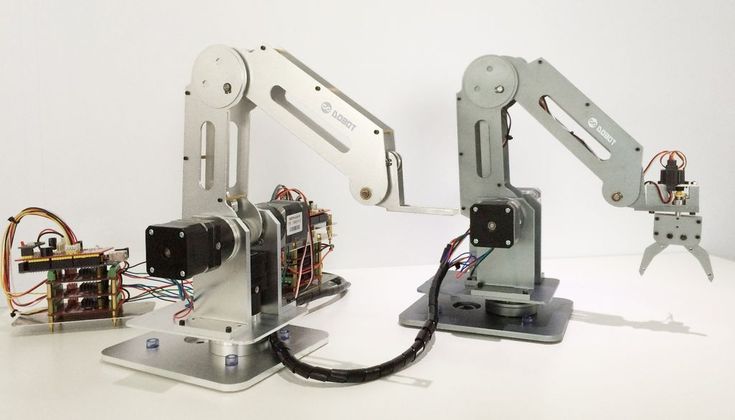

UFactory uArm

UArm is probably one of the most versatile of all the robot arms on this list. At the moment, this design already has the third release version - uArm Swift and more functional Swift Pro.

This open source robot arm is fully compatible with Arduino, Raspberry Pi and Seeed Studio Grove kits. It's unique in that the Swift Pro can do laser engraving and 3D printing - provided it's equipped with the right heads - and can "learn" the movements without the need for a computer.

This is a 4DOF manipulator with an accuracy of 0.2 millimeters.

You can find more information and where to buy it on the UFactory product page.

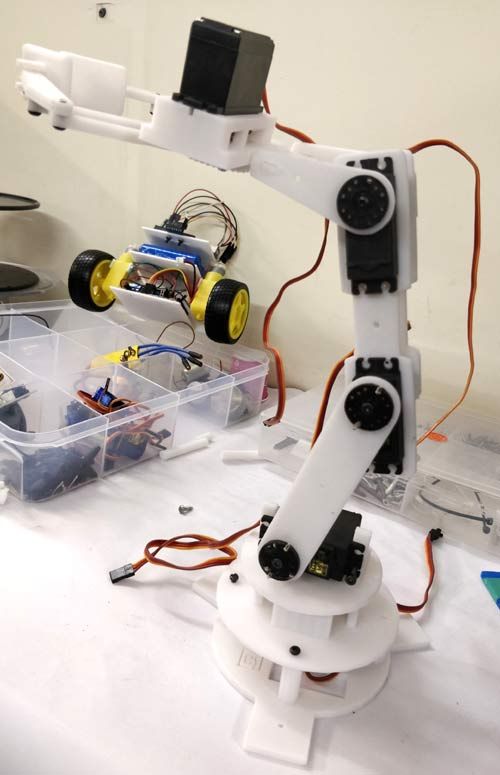

Thor

This arm, developed by Hackaday AngelLM, is completely open source and can be used for 3D printing. This is a 6DOF paddle with a maximum payload of 750 grams and a unique design for great flexibility.

You can find all the 3D printing files for this robot on the Thor project page.

EEZYbotARM MK2

The EEZYbotARM MK2 is a 4DOF reference arm that is fully 3D printed with excellent building instructions. This robotic arm has won several competitions and is probably one of the easiest robotic arms to make. An MK3 version is also being developed.

You can find complete assembly instructions on the EEZYbotARM web page.

Roboteurs RBX1

This is another great fully 3D printed robot arm that has amazing flexibility and aesthetics. In addition to purchasing the components yourself, Roboteurs offers a complete parts kit with a proprietary stepper motor driver to run the RBX1. All you need is a Raspberry Pi and a 3D printer. This manipulator is a 6DOF type design and has a beautiful appearance.

You can find the complete specification and parts kit on the Roboteurs product page.

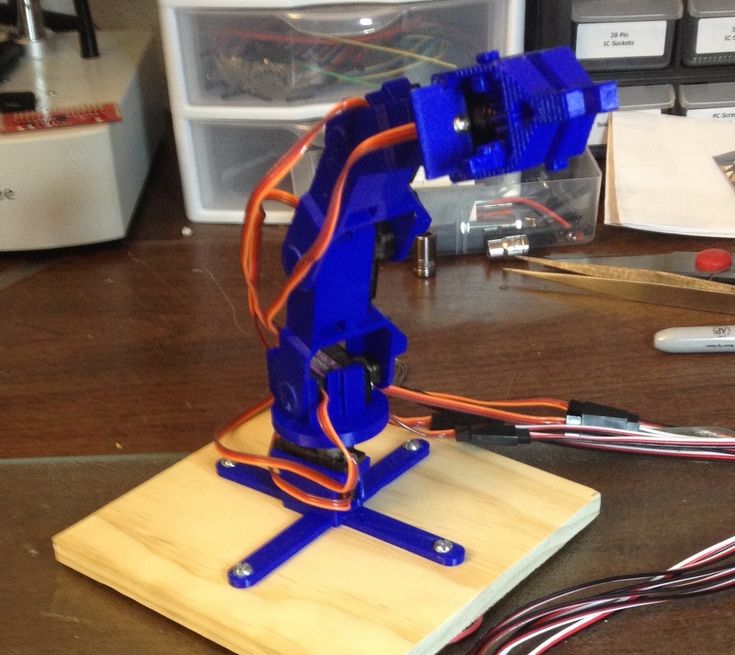

LittleArm

LittleArm, designed by Slant Concepts on Hackaday.io, is the simplest robotic arm on this list. With only 3DOF, this arm can be a great introduction to Arduino programming for students and opens exciting doors of new technologies for newcomers to the world of 3D printing and robotics.

With only 3DOF, this arm can be a great introduction to Arduino programming for students and opens exciting doors of new technologies for newcomers to the world of 3D printing and robotics.

This fully 3D printed arm is very easy to assemble. The creators even developed an application with a simple interface for computers that can be used with this robot.

You can find full documentation on the LittleArm project page.

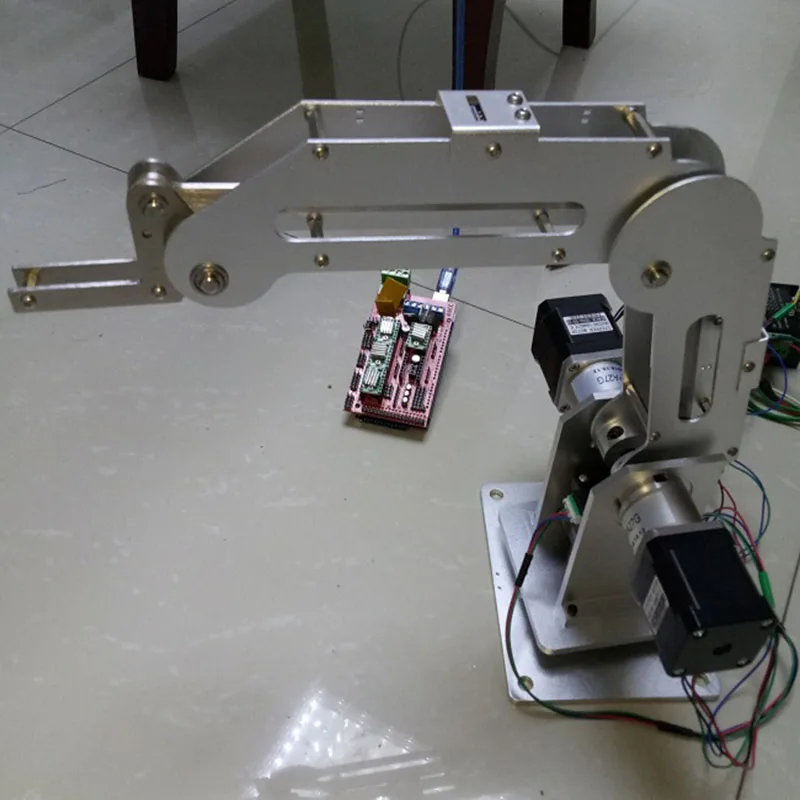

3D Printable Robot Arm

Created by Andreas Helldorfer on Hackaday.io. It's a large arm, fully 3D printed, with many uses. The creator developed it for 4 iterations before making a really worthy industrial design that is available to everyone. With a 6DOF design and a maximum payload of up to 2kg, this arm can really be used in many applications.

To find the 3D print files for this arm and the full specification, visit the project page.

MeArm

MeArm is one of the most popular manipulators and for good reason. It consists of simple parts that can be laser cut or 3D printed and features a simple yet robust 4DOF construction.

It consists of simple parts that can be laser cut or 3D printed and features a simple yet robust 4DOF construction.

This design is so popular that two others on this list copy it. This is a manipulator equipped with four servos and either an Arduino or a Raspberry Pi. It is available in several different colors as a kit, or you can make all the parts yourself.

For pre-assembled kits, check out the MeArm product page.

For 3D printing files, take a look at MeArm on Thingiverse.

Zortrax Robotic Arm

The 5DOF Zortrax Robotic Arm is not the strongest for its size, with a maximum payload of only 100 grams, but it has a very impressive design. And it's a fully 3D printed arm, making it worthy of a mention on the current list. Its uniqueness lies in the fact that only three axles are driven, while the rest are set manually.

This manipulator is primarily used for supplying a set of interchangeable tool heads.

For a complete list of part files, including those for 3D printing, visit the project page.

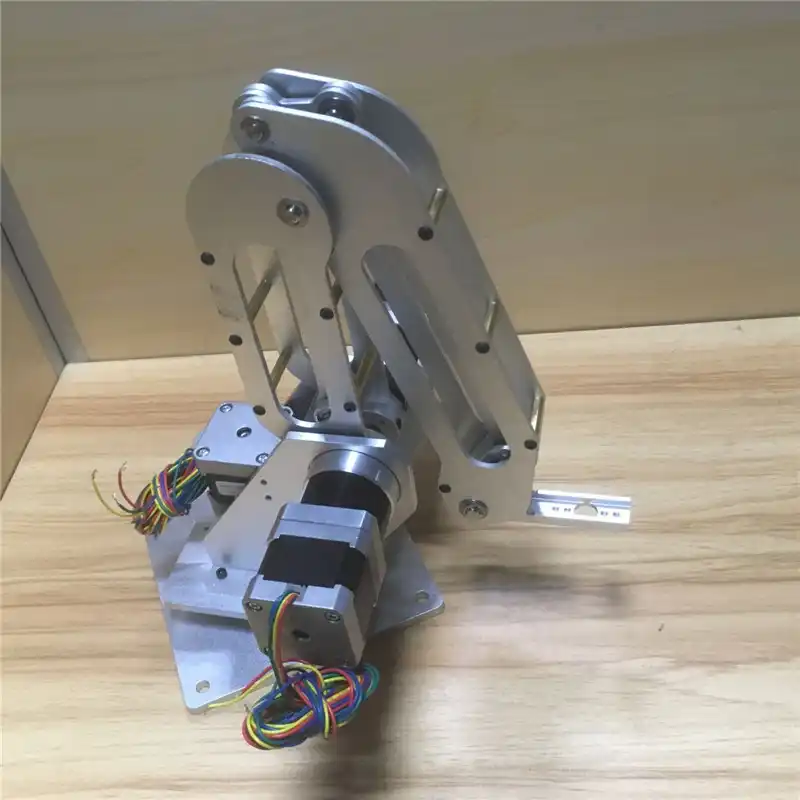

BCN3D Moveo

BCN3D Moveo is an impressive Arduino controlled 4DOF robot arm. It is fully 3D printed, open source, and has been well tested as a mockup for educational purposes and is already in active use in educational institutions.

Being open source, this manipulator is not limited to its intended use and, as such, can be modified to perform all kinds of tasks and can be used as a dedicated household apprentice or used on an industrial scale.

For more information, visit the BCN3D Moveo webpage.

OWI Robotic Arm Edge

Another 4DOF design, the OWI Robotic Arm Edge is a simple manipulator designed for educational purposes. It is only available as a kit.

When powered by DC motors without encoders, accuracy is limited, making this manipulator more suitable for use as a toy. We included it on this list because it's a fantastic kit for students interested in robotics and technology, and it can be a great "desk toy" during boring lunch breaks. It can also be extensively modified to serve as a base platform for Arduino projects and other DIY developments.

It can also be extensively modified to serve as a base platform for Arduino projects and other DIY developments.

You can buy it on the OWI website, well, or Amazon, Aliexpress is also at your service.

Manipulator 3d model

DOWNLOAD

-

Rating:

-

Difficulty:

Medium -

Weight:

9.72 MB -

Parts:

22 pcs.

Everyone knows the robotic arm that is used in factories and other enterprises. Perhaps the robotic arm is the most popular model for assembly and control experiments among robotics fans. In addition, she teaches children very well at RobotON robotics circles in Nizhny Novgorod, the guys study her with great pleasure, programming and forcing them to perform various manipulations. Of course, this robot has a lot of details, and printing them with high quality on a 3D printer is not an easy task for a beginner. But for this, we have prepared articles on 3D printing that will definitely help you cope with this task.

But for this, we have prepared articles on 3D printing that will definitely help you cope with this task.

The instructions for assembling the robotic arm look very simple. It is worth collecting in 3 stages. First you need to assemble the base - the base on which the robot rotates around its axis in azimuth. Then you need to assemble the claw, and then the multi-lever mechanism of the crane itself. When assembling it, you need to make sure that each assembly rotates very easily. Otherwise, the servomotors will not have enough power to move the entire structure.

What causes poor mobility? Well, first of all, it can be caused by 3D printing defects. When you print a 3D model with a certain size of screw holes, you need to take into account the flow of plastic around the edges. That is, for example, if you have a round hole, then most often when printing, its diameter will decrease by 0.5 mm or even 1 mm. Because of this, the screw will hardly fit into this hole and cut the thread there. Therefore, there are 3 ways out here: pre-clear the hole with a screwdriver (or something else), develop a movement along the thread by assembling the knot, or simply put this error in the 3D model. This problem occurs depending on the printer, so it is quite individual.

Therefore, there are 3 ways out here: pre-clear the hole with a screwdriver (or something else), develop a movement along the thread by assembling the knot, or simply put this error in the 3D model. This problem occurs depending on the printer, so it is quite individual.

Another reason why a structure can be too stiff is overtightening the bolts or using the wrong sizes of connecting elements.

Features:

An important detail of the assembly is the pre-setting of the servos before attaching them to the crane or claw. The fact is that these places, due to the design and capabilities of servo motors, have dead zones. Therefore, before installing the servos on the crane, you need to program them at an angle of 90 degrees to be able to move the crane both to the right and to the left. We set the claw servomotor to 0, close its blades and fix it with a gear.