3D printing and intellectual property

How 3D Printing Challenges Trademark, Copyright, and Patents

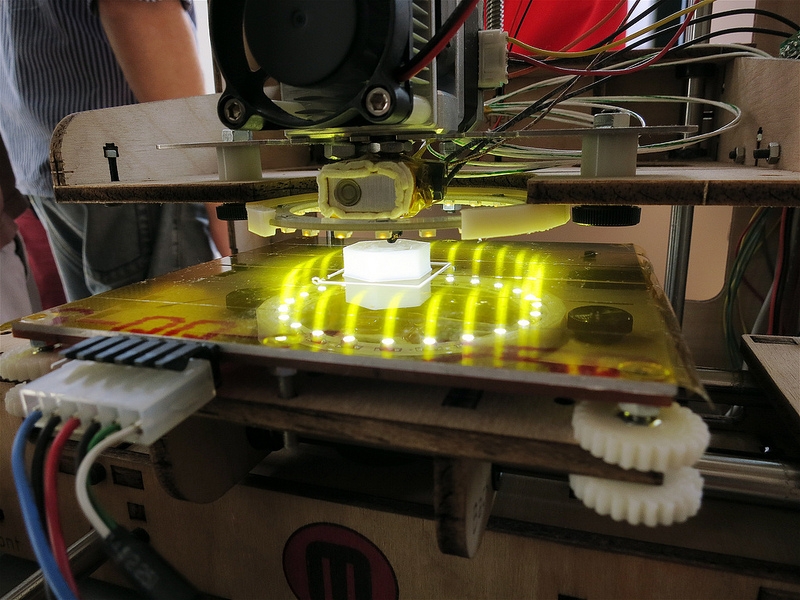

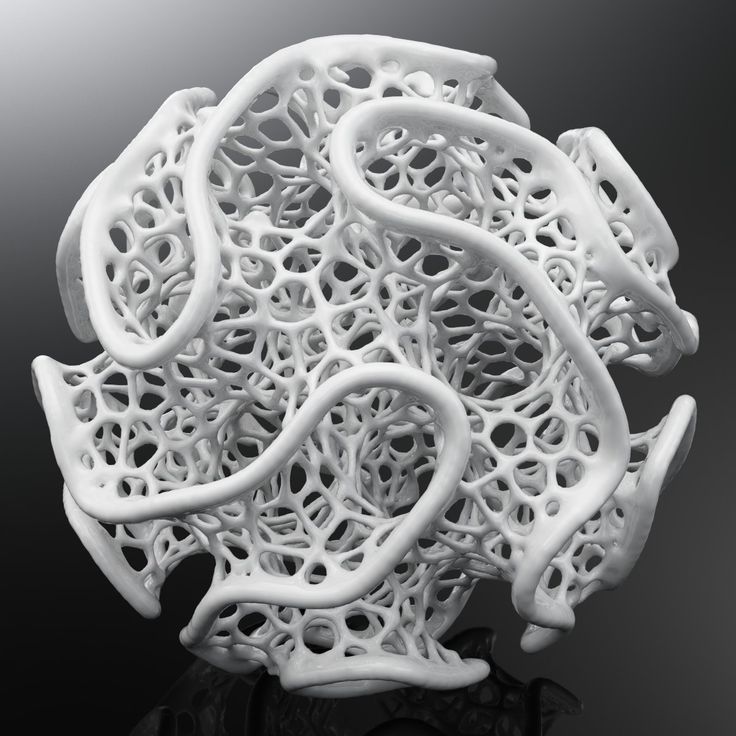

Skip to content3D (three-dimensional) printing technology began in the 1980s, however, the increase and advancement of technology has allowed consumers the ability to access low cost 3D high-performance printers. With great technology comes great challenges to existing laws that never could have anticipated the future impact of these rapidly changing industries. With the market for 3D printers growing by 20% every year, any person can now own a 3D printer, which has vast implications on trademark, copyright, and patent law.

Recently, while dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, a hospital in Italy experienced a shortage of special valves used in breathing machines needed by COVID-19 patients. Local engineers recreated the valve design digitally and printed it with a 3D printer, without the permission of the patent holder. The incident, which involved a U.S. company, not only highlights potential ethical concerns in enforcing such intellectual property (IP) rights during a medical emergency, but also the relative ease with which infringement of IP rights can occur through the use of 3D printers.

Trademark Law

A trademark is an identifying mark like a name, logo, or slogan, that allows consumers to connect a good or service to its source. In the United States, trademark rights are conferred by first use, not first to file a registration; however, registering a trademark federally provides significantly more legal protection and options to the rights holder.

Trademark infringement occurs when the mark is used without permission in connection with a sale and is likely to lead to confusion, deception, or mistake as to the source of the goods or service. Trademark infringement using 3D printers can lead to consumer confusion when infringing material is placed in the stream of commerce and, in turn, damage the reputation and business of the rights holder. It will not likely matter if the trademark appears differently and not identically when printed in 3D because the standard of determining if the unauthorized mark will lead to confusion is whether a consumer is likely to be confused as to the source of the mark.

Copyright Law

Copyright is a legal right held by the creator of an original work. This right arises immediately after an original, tangible work is created. There is no requirement to register a work with the U.S. Copyright Office; however, doing so provides added legal protection and tools to enforce the copyright.

Copyright infringement refers to the unauthorized reproduction, duplication, distribution, or creation of a derivative work of an original work. With advanced 3D printing technology, any person may scan a copyrighted work and reproduce that original work. If any object is scanned without the original owner’s permission, and printed on a 3D printer, it may constitute copyright infringement.

In an innovative response to the growing trend of 3D printing, Hasbro announced a partnership with the 3D printing marketplace, Shapeways in 2014, to allow My Little Pony fans to freely create fan art with 3D printers. This unique strategy allowed Hasbro to keep control over their copyright and find a compromise for fans.

Patent Law

A patent provides legal rights to the owner of an invention or mechanism that prevents any other person from manufacturing, using, selling or importing the product, substance, or process under patent protection. There are three different types of patents: utility patents, design patents, and plant patents.

As with trademark law and copyright law, if a person takes a product or process, and reproduces it with a 3D printer, that may constitute patent infringement. Patent infringement occurs when a party makes, uses, sells, or offers the invention without the permission of the patent holder. Patent holders should monitor the marketplace vigilantly for infringement of their 3D printed products.

Contact an Experienced Intellectual Property Attorney

If you are concerned about how the growing trend of 3D printing may affect your intellectual property rights, contact an experienced intellectual property attorney at The Myers Law Group at 888-676-7211 or online today.

Categories

- Business

- Business Formation

- Business Litigation

- Copyright

- Current Issues

- Intellectual Property

- Patents

- Real Estate

- Trade Secrets

- Trademarks

Archives

- May 2022 (6)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (4)

- February 2022 (4)

- July 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (2)

- September 2019 (3)

- August 2019 (2)

- June 2019 (3)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- January 2019 (3)

- May 2018 (2)

- April 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- November 2017 (3)

- September 2017 (2)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (2)

- May 2017 (2)

- March 2017 (3)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (1)

- October 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (3)

- June 2016 (1)

- September 2015 (3)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (5)

- May 2015 (7)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (6)

- February 2015 (7)

Recent Posts

- Three Songwriter’s Claim Sam Smith and Normani’s “Dancing with a Stranger” Copied Their Song of the Same Name

- Dua Lipa Sued Twice in One Week for Copyright Infringement Over Hit Song “Levitating”

- Why Is Litigation Bad for Business?

- What Is Litigation in a Business?

- Pay-Per-View Provider’s $100 Million Suit Against Alleged Illegal Streamers for Jake Paul vs.

Ben Askren Fight Ends in Failure

Ben Askren Fight Ends in Failure

3D printing and IP law

February 2017

By Elsa Malaty, Lawyer, Associate in the law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP, and Guilda Rostama, Doctor in Private Law, Paris, France

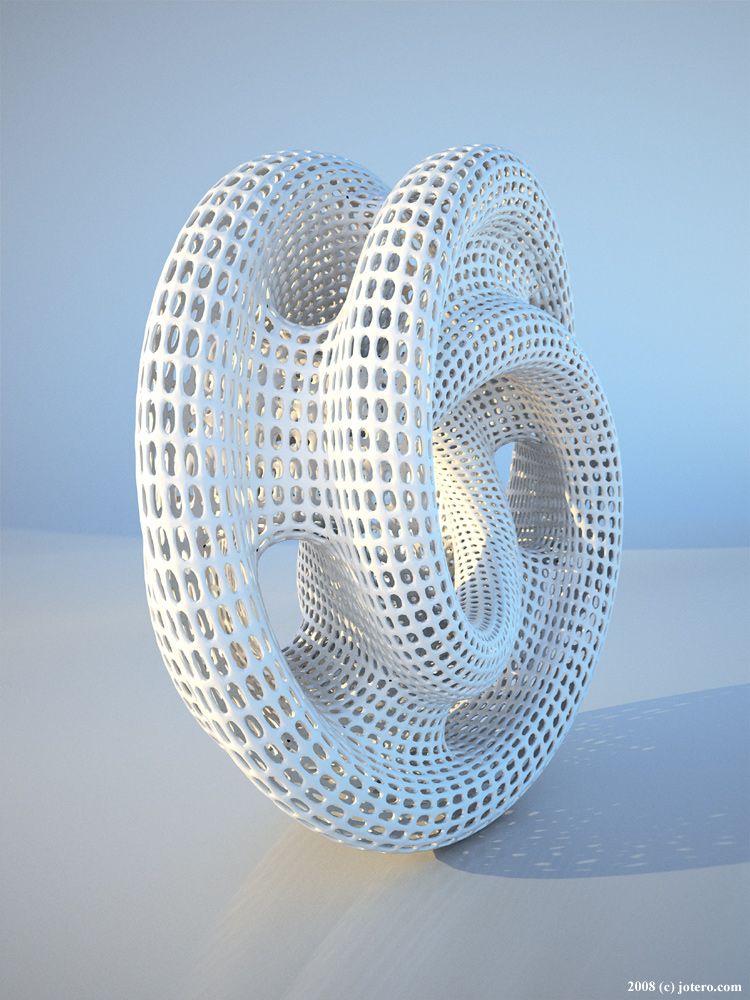

3D printing technology emerged in the 1980s largely for industrial application. However, the expiry of patent rights over m�any of these early technologies has prompted renewed interest in its potential to transform manufacturing supply chains. The availability of low-cost, high-performance 3D printers has put the technology within reach of consumers, fueling huge expectations about what it can achieve. But what are the implications of the expanding use of this rapidly evolving and potentially transformative technology for intellectual property (IP)?

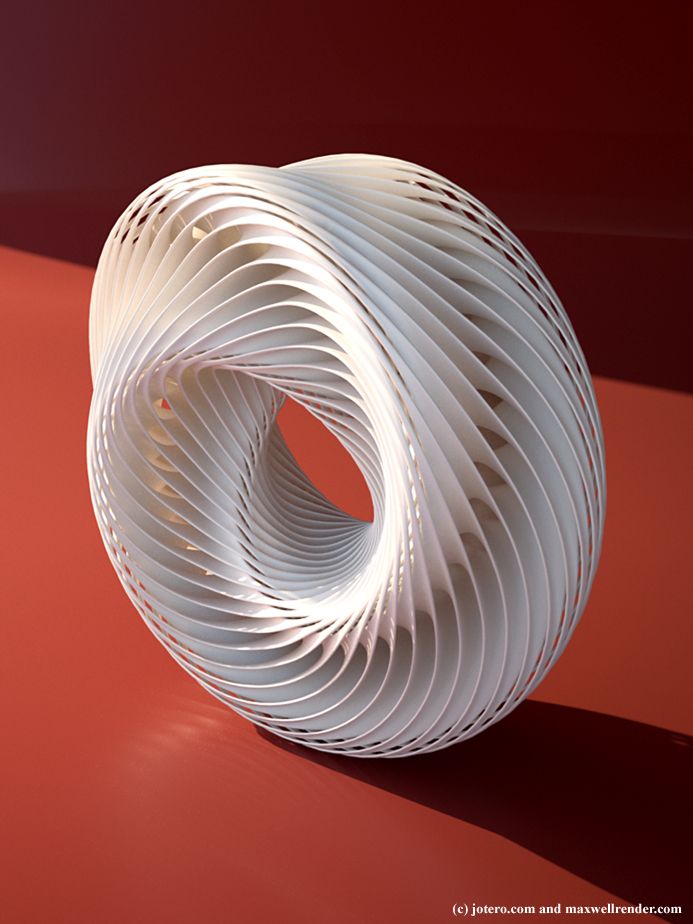

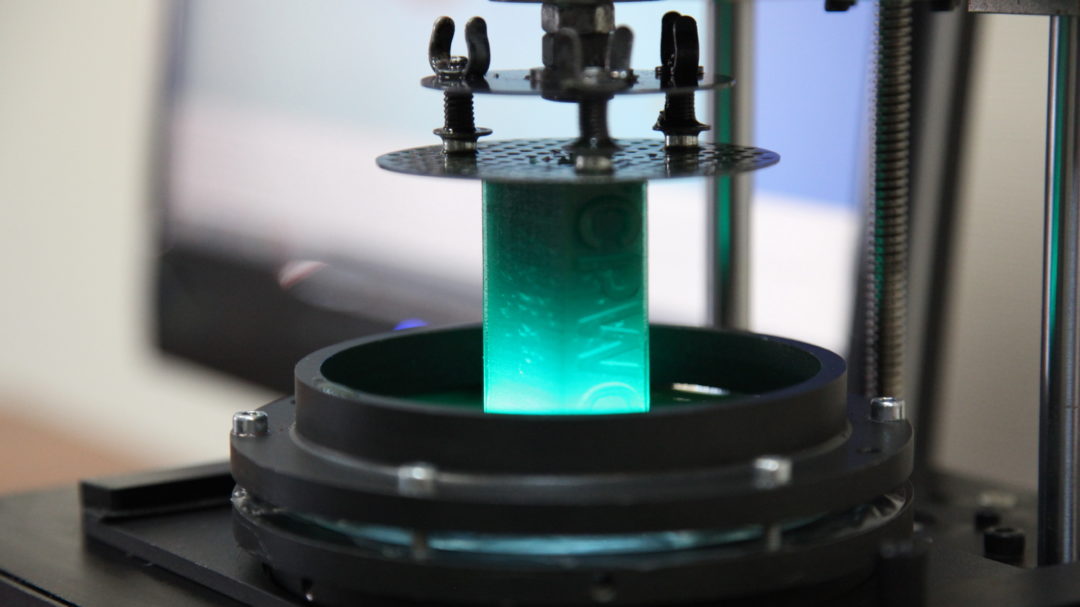

Using a commercially available 3D printer, researchers at the National University of Singapore have found a way to print customizable tablets that combine multiple drugs in a single tablet so doses are perfectly adapted to each patient. (Photo: Courtesy of the National University of Singapore).3D printing in a nutshell

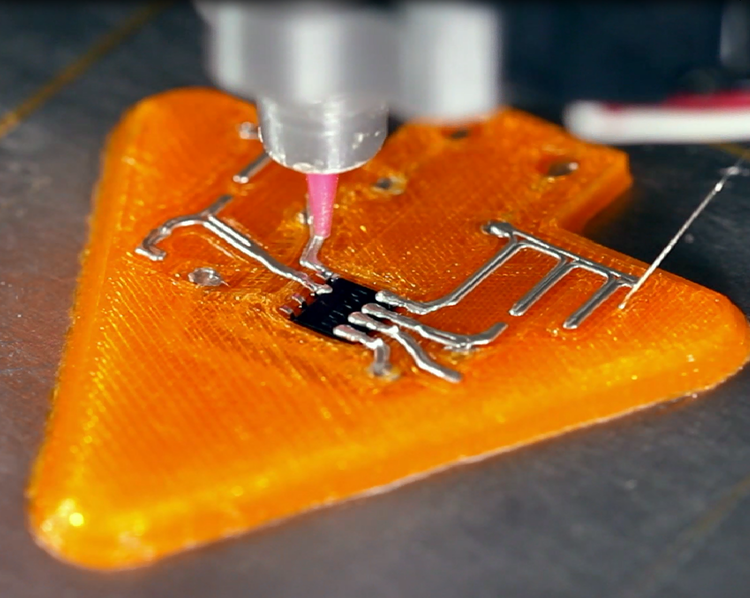

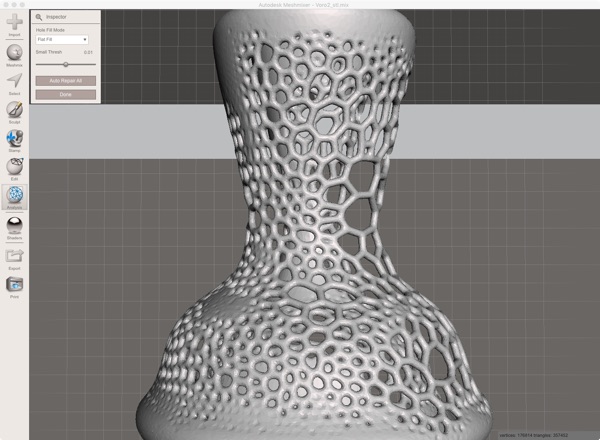

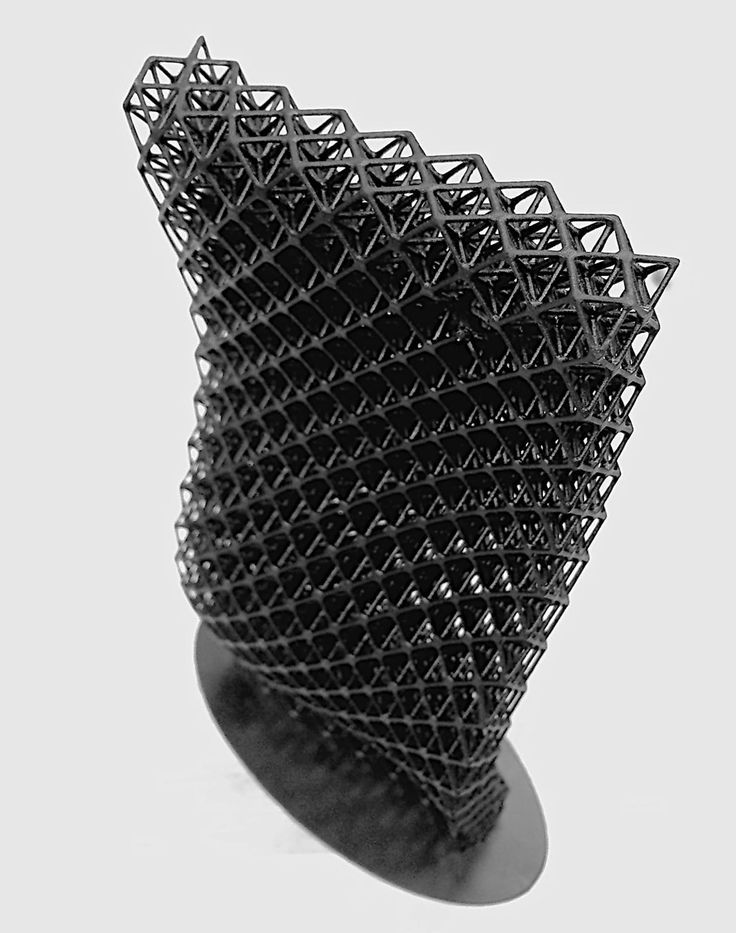

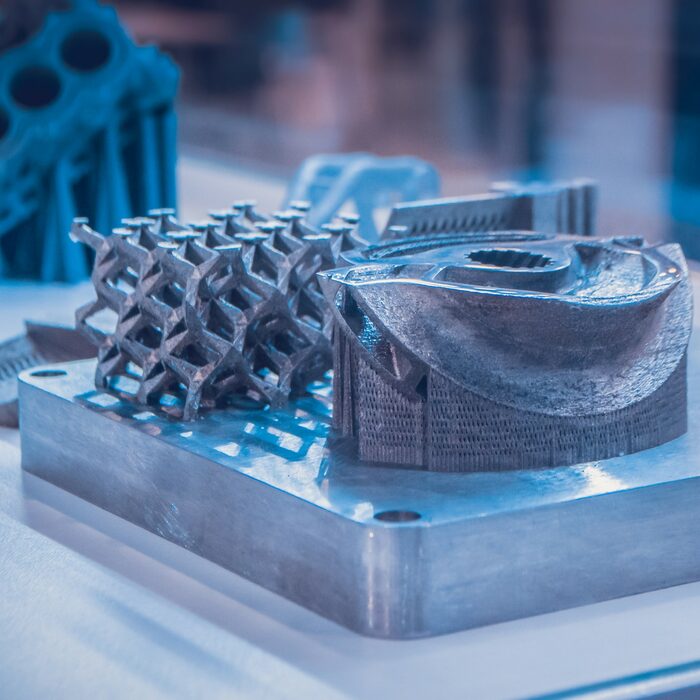

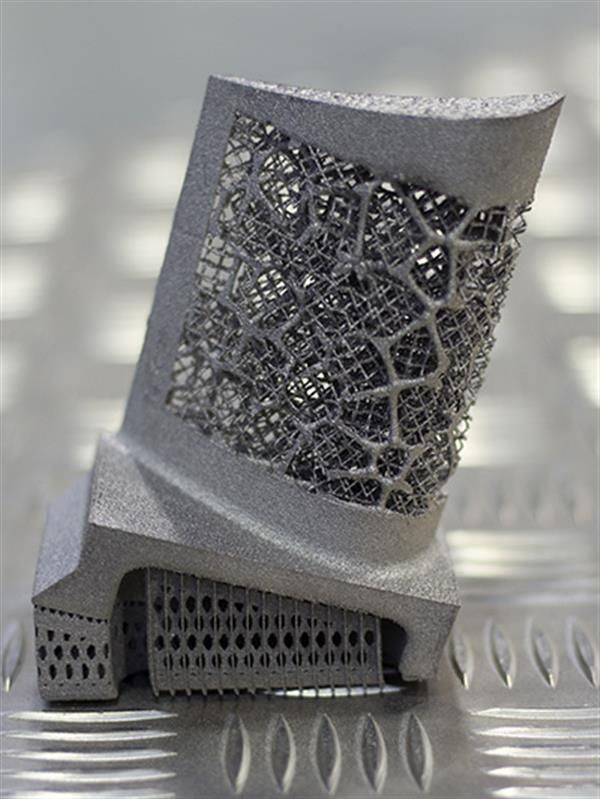

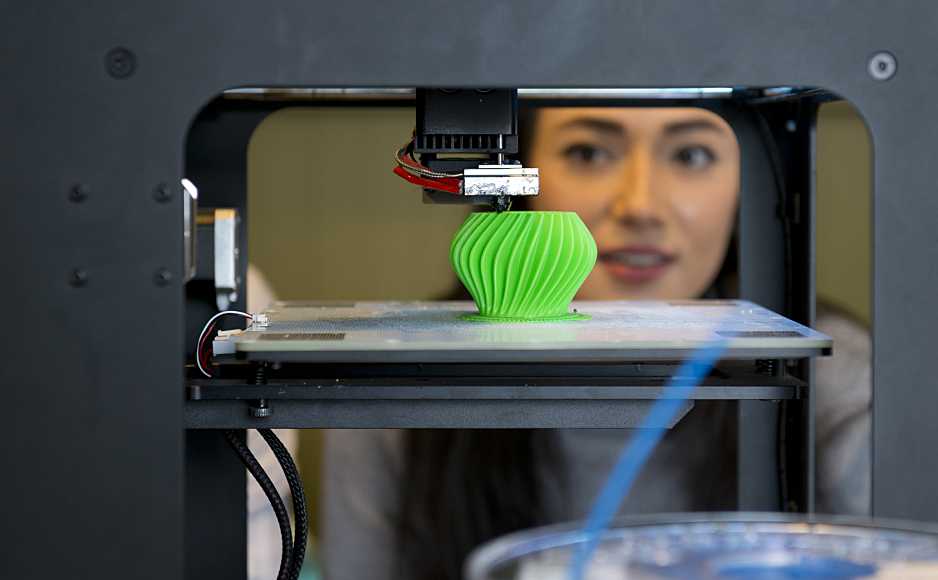

(Photo: Courtesy of the National University of Singapore).3D printing in a nutshellThe 3D printing process starts either with a digital file in which the object to be printed is digitally formatted using either 3D print software, or a 3D scanner. The file is then exported to a 3D printer using dedicated software, which transforms the digital model into a physical object through a process in which molten material is built up layer upon layer until the finished object emerges. This process is also referred to as additive manufacturing.

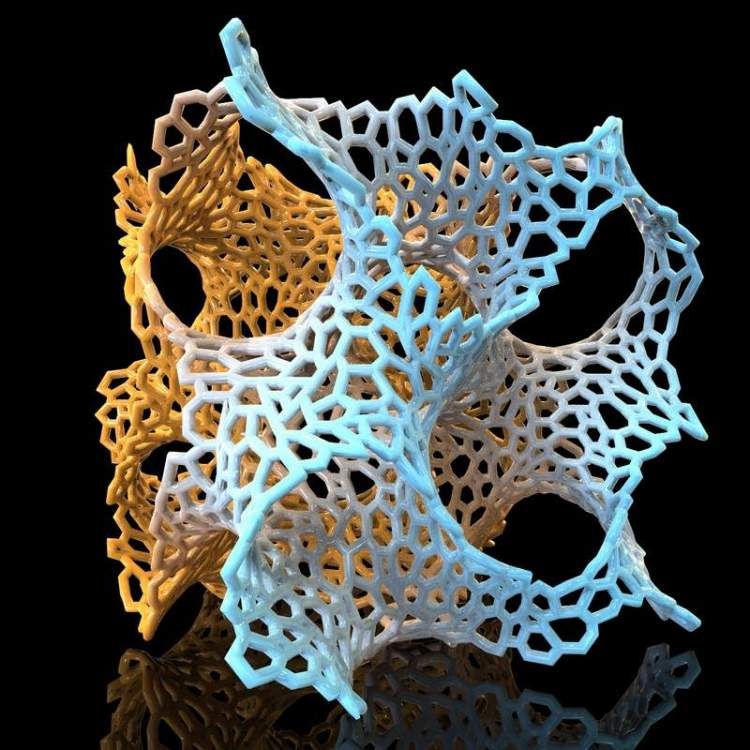

The 3D printers available today use a variety of materials ranging from plastics to ceramics, and from metals to hybrid materials. The technology is evolving at a breathtaking pace. For example, MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory recently developed a 3D printing technique to print both solid and liquid materials at the same time using a modified off-the-shelf printer, opening up a huge range of possible future applications.

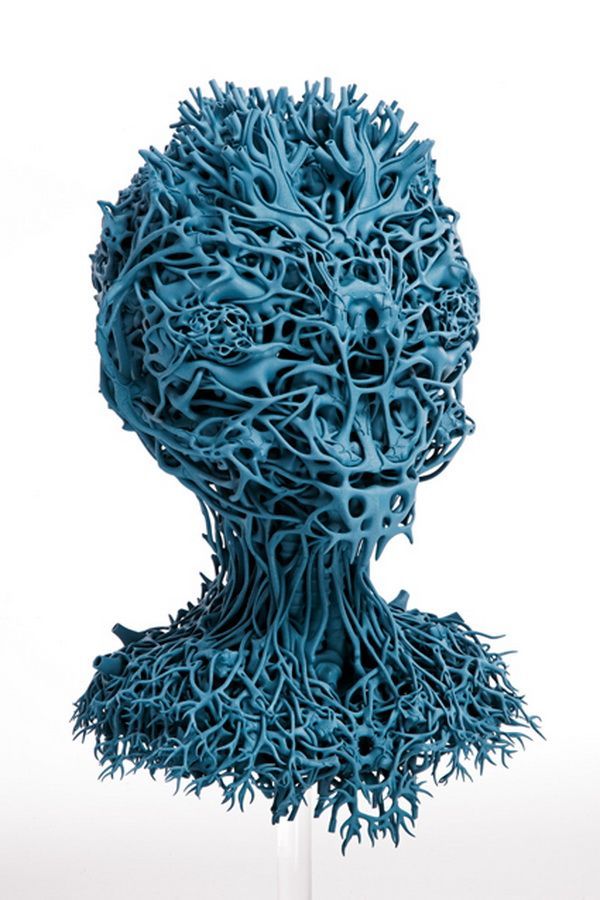

3D printing technology is evolving at a breathtaking pace, with applications in areas ranging from food and fashion to regenerative medicine and prosthetics.

The expanding range of materials used for 3D printing means that the technology’s application is having an impact on a whole range of industries, fostering new opportunities for innovation and business development.

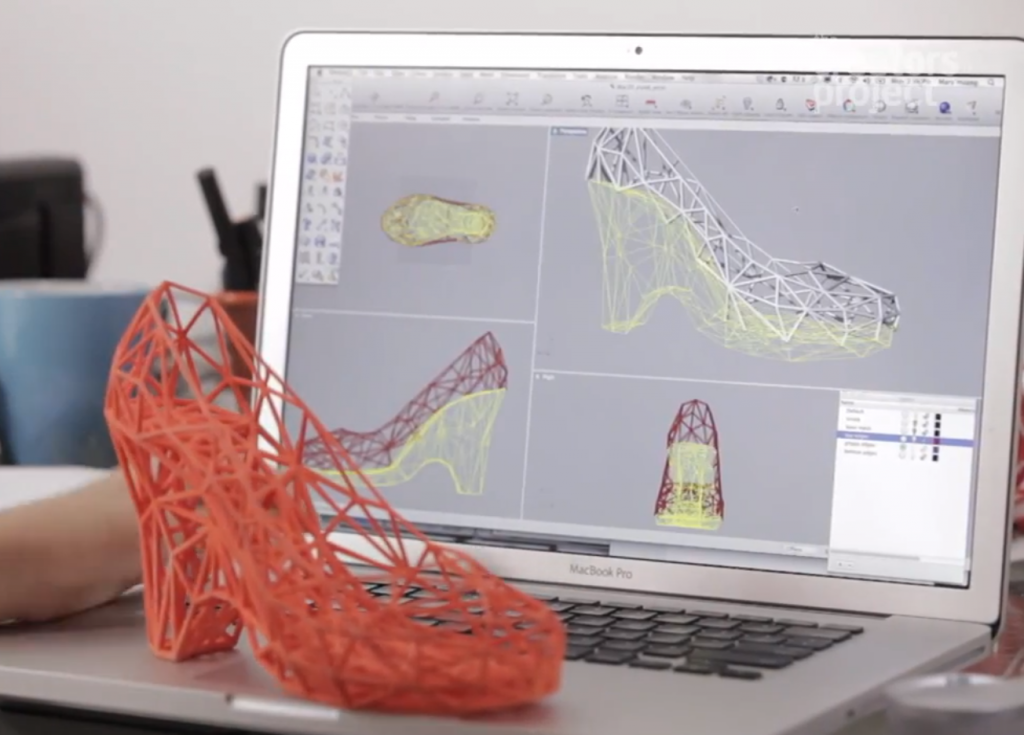

Even food is being 3D printed! It makes it possible to automate certain time-consuming aspects of food preparation and assembly, makes it easier to create freshly made snacks, has huge scope for food customization and can convert alternative ingredients like proteins from algae, beet leaves and insects into tasty meals! (Photo: Courtesy of www.naturalmachines.com).Within the medical field, for example, researchers at the National University of Singapore have found a way to print customizable tablets that combine multiple drugs in a single tablet, so that doses of medicines are perfectly adapted to the needs of individual patients. 3D printing is also making its mark in the fashion industry, as evidenced by the unveiling at New York Fashion Week in September 2016 of “Oscillation”, a multi-colored 3D-printed dress by threeASFOUR and New York-based designer Travis Finch. Even the agro-food industry is exploring the potential of 3D printing for customized food products.

3D printing is also making its mark in the fashion industry, as evidenced by the unveiling at New York Fashion Week in September 2016 of “Oscillation”, a multi-colored 3D-printed dress by threeASFOUR and New York-based designer Travis Finch. Even the agro-food industry is exploring the potential of 3D printing for customized food products.

Materialise’s consumer 3D printing service, i.materialise, featured in

the fashion show of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp,

Belgium, in 2016. The sunglasses are fully 3D printed “as a total

concept with no need for hinges or assembly” (Photo: Courtesy

of i.materialise.com).

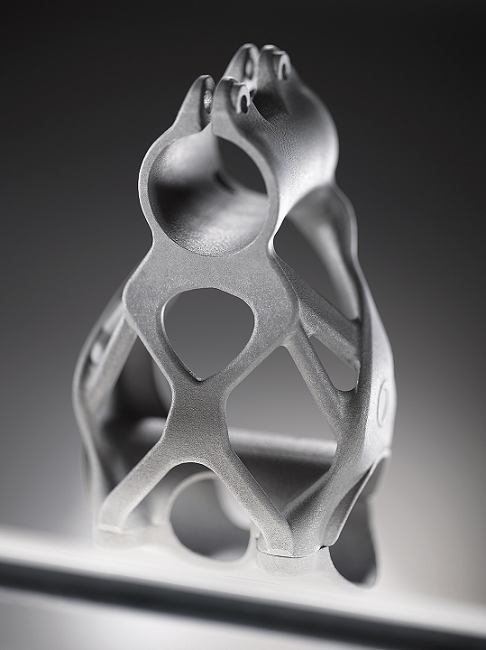

The potential advantages of 3D printing are numerous for innovation-intensive companies. In particular, 3D printing allows them to reduce their overheads when developing, designing and testing new products or improving existing ones. They no longer have to pay for costly prototypes but can rapidly and cheaply undertake multiple iterations of complex elements in-house using 3D printers.

They no longer have to pay for costly prototypes but can rapidly and cheaply undertake multiple iterations of complex elements in-house using 3D printers.

Recognizing the transformative potential of 3D printing, many countries have already adopted, albeit unevenly, different strategies to create an economic and technological ecosystem that favors its development. The European Commission, for example, has identified 3D printing as a priority area for action with significant economic potential, especially for innovative small businesses.

Lawyers in many countries are considering the capacity of existing legal provisions to orient this new technology, particularly with respect to intellectual property (IP). 3D printing technology affects virtually all areas of IP law: copyright, patent law, design law, and even geographical indications. The question is, can IP laws in their current form embrace such an all-encompassing technology or do they need to be reformed? Does existing IP law ensure adequate protection for those involved in 3D printing processes and the products they make? Or would it make sense to consider creating a sui generis right for 3D printing to address emerging challenges, along the lines of arrangements in place in some jurisdictions for the protection of databases?

How current IP law handles 3D printingOne of the main concerns about 3D printing is that its use makes it technically possible to copy almost any object, with or without the authorization of those who hold rights in that object. How does current IP law address this?

How does current IP law address this?

Protecting an object from being printed in 3D without authorization does not raise any specific IP issues as such. Copyright will protect the originality of a work and the creator’s right to reproduce it. This means that if copies of an original object are 3D printed without authorization, the creator can obtain relief under copyright law. Similarly, industrial design rights protect an object’s ornamental and aesthetic appearance – its shape and form – while a patent protects its technical function, and a three-dimensional trademark allows creators to distinguish their products from those of their competitors (and allows consumers to identify its source).

Conventional eyeware design usually begins with the frameinto which corrective lenses are fitted. This can have a negative

impact on lens alignment and performance. With custom

software developed by Materialise, the Yuniku platform uses

3D scanning, parametric design automation and 3D printing to

design the customer’s chosen frame around the optical lenses

they require for a perfect look and fit.

(Photo: Courtesy of i.materialise.com)

Many commentators believe that a 3D digital file may also be protected under copyright law in the same way that software is. The justification for such protection is that “the author of a 3D file must make a personalized intellectual effort so that the object conceived by the author of the original prototype can result in a printed object,” notes French lawyer Naima Alahyane Rogeon. With this approach, the author of a digital file that is reproduced without authorization could claim a moral right in the work if their authorship is called into question. Article 6bis of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, which establishes minimum international standards of protection in the field of copyright, states that the author has “the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation. ”

”

If the printed object is protected by a patent, certain national laws, for example the Intellectual Property Code of France (Article L 613-4), prohibit supplying or offering to supply the means to use an invention without authorization. Following this approach, patent owners should be able to seek redress from third parties for supplying or offering to supply 3D print files on the grounds that these are an “essential element of the invention covered by the patent”.

What is the situation for hobbyists?But what is the situation with respect to hobbyists who print objects in the privacy of their own home? Are they at risk of being sued for infringement?

The standard exceptions and limitations that exist in IP law also naturally apply to 3D printing. For example, Article 6 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS), which has been transposed into EU law (EU Directive 2008/95/CE, Article 5), limits trademark protection to use “in the course of trade”. Similarly, with respect to patent law Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement states that member countries “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent”. Some national laws consider that the rights of the patent holder do not include acts performed in private for non-commercial purposes. In other words, when an object that is protected by a trademark or a patent is printed for purely private use, it is not considered an infringement of IP rights.

Similarly, with respect to patent law Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement states that member countries “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent”. Some national laws consider that the rights of the patent holder do not include acts performed in private for non-commercial purposes. In other words, when an object that is protected by a trademark or a patent is printed for purely private use, it is not considered an infringement of IP rights.

Travis Fitch, 3D printed by Stratasys, a leading 3D print solutions

company based in the United States, was unveiled at New York Fashion

Week in September 2016. “3D printing is transformative for designers

aiming to take complex designs and realize them as a wearable garment,”

explains threeASFOUR’s Adi Gil (Photo: Elisabet Davids, Jan Klier).

In the area of copyright, the rights granted to authors can be limited according to the so-called three-step test. Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement states that “members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.” Accordingly, some countries have established a “right to private copying” authorizing a person to reproduce a work for private use. Countries often then levy a fee on storage devices to compensate any losses incurred by the rights holder; some countries are exploring the idea of levying a fee to offset private 3D copying. However, some lawmakers consider it premature to extend such a fee to 3D printing, as this would constitute “an inadequate response or even a negative message for companies” and would put a brake on the development and uptake of 3D printing.

Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement states that “members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.” Accordingly, some countries have established a “right to private copying” authorizing a person to reproduce a work for private use. Countries often then levy a fee on storage devices to compensate any losses incurred by the rights holder; some countries are exploring the idea of levying a fee to offset private 3D copying. However, some lawmakers consider it premature to extend such a fee to 3D printing, as this would constitute “an inadequate response or even a negative message for companies” and would put a brake on the development and uptake of 3D printing.

IP law in its current form, therefore, appears sufficient to effectively protect both 3D files and those using 3D printing technologies for non-commercial purposes. That said, the specificities of the 3D printing process mean that there are a number of questions that the courts will inevitably need to address. For example, who owns an object when it is first conceived by one individual, digitally modeled by another, and printed by a third? Can the person who designed the work and the person who digitally modeled it be considered co-authors of a collaborative work under copyright law? And if the object qualifies for patent protection, would these same individuals be considered co-inventors?

That said, the specificities of the 3D printing process mean that there are a number of questions that the courts will inevitably need to address. For example, who owns an object when it is first conceived by one individual, digitally modeled by another, and printed by a third? Can the person who designed the work and the person who digitally modeled it be considered co-authors of a collaborative work under copyright law? And if the object qualifies for patent protection, would these same individuals be considered co-inventors?

Other important questions include the type of protection that should be available to owners of 3D printers. Since their financial investment enables the creation of an object, might they qualify for the same type of related rights protection as that enjoyed by music producers whose investment enables the creation of sound recordings? And is the digitization of a pre-existing object considered an act of infringement simply because it is printed or its base file is loaded onto an online sharing platform for downloading? These issues still need to be ironed out.

In the meantime, to curb unauthorized use, if the object is protected by copyright, rights holders can make use of technological protection measures, the circumvention of which is expressly forbidden under the WIPO Copyright Treaty (Article 11). These measures make it possible, for example, to mark an object and its associated 3D print file with a unique identifier to monitor use.

Close collaboration between rights holders and 3D printer manufacturers in applying these measures to models intended for 3D printers could be beneficial. Similarly, partnerships with sharing platforms that make 3D files publicly available could help curb unauthorized use.

With such measures in place, it would be possible to set up a legal offering of downloadable 3D print files or 3D-printed objects. While online 3D printing services such as i.materialise are now readily available, one can imagine that their future evolution will follow that of online music delivery with the emergence of subscription models that allow users to download 3D print files in return for a monthly fee. Indeed, these are already available for 3D printing software, for example through Fusion 360, Autodesk’s cloud-based product innovation platform.

Indeed, these are already available for 3D printing software, for example through Fusion 360, Autodesk’s cloud-based product innovation platform.

Benjamin Hubert from the Layer design agency. The GO

wheelchair prototype was developed in collaboration with

Materialise, a leading 3D print software, engineering

and services provider based in Belgium

(Photo: Courtesy of i.materialise.com).

The experience of online music streaming platforms suggests that such arrangements could have a positive impact on infringement levels. The 2016 Australian Consumer survey on Online Copyright Infringement, for example, showed a 26 percent decrease in the number of Australian internet users accessing unlawful content online and a marked increase in the uptake of streaming services.

3D printing technologies have many life-enhancing, even revolutionary, applications, from regenerative medicine to prosthetics and from complex airplane components to food and fashion. As the use and application of this exciting technology gathers pace and digital transformation continues to gain momentum, 3D printing is likely to become deeply embedded in our daily lives. Beyond the IP-related questions outlined above, the use of 3D printing raises other important legal questions, for example in relation to quality assurance, legal liability and public order. All of these issues still need to be resolved and they can be.

As the use and application of this exciting technology gathers pace and digital transformation continues to gain momentum, 3D printing is likely to become deeply embedded in our daily lives. Beyond the IP-related questions outlined above, the use of 3D printing raises other important legal questions, for example in relation to quality assurance, legal liability and public order. All of these issues still need to be resolved and they can be.

But as the potential of this fascinating technology continues to unfold, the real challenge will be to fully understand the implications of its uptake and use on manufacturing processes across the economy and its impact on our daily lives.

Related Links

- 3D Printing Is Here to Stay!

3D printing and intellectual property - Stepline.kz

It's no secret that modern 3D printing technologies are changing our world, opening up a whole range of new possibilities. Already now we can safely say that with the help of this technology you can get almost any item or object that will cost you several times cheaper than its original. On the one hand, this opens up new opportunities for consumers, industry, medicine and many other industries, which is certainly very good. But at the same time, it is worth being aware of the possible risks, as well as problems that may be the result of rapid development and improvement 3D printing , specifically infringement of intellectual property rights.

On the one hand, this opens up new opportunities for consumers, industry, medicine and many other industries, which is certainly very good. But at the same time, it is worth being aware of the possible risks, as well as problems that may be the result of rapid development and improvement 3D printing , specifically infringement of intellectual property rights.

First, let's say a few words about the essence of 3D printing and how printers work. And so, we want to get some object using the new 3D printing technology. To do this, we will need to create (or simply borrow) a digital 3D model of the object, which is then opened through special software and used by the 3d printer to make a material object. The principle of operation is in many ways similar to the operation of a conventional printer, but here it is no longer a two-dimensional plane that is used, but a three-dimensional space. The 3D model contains all the necessary information that the printer uses to print and form a three-dimensional object. Depending on the technology used ( FDM, SLA, SLS ), the appropriate material is selected, after which the printer forms the object we have chosen from it in layers. As a rule, plastic, metal, glass, ceramics or wood in the desired form (filament, powder, etc.) is used as the main material, but modern production 3D printers are able to work with many other types of raw materials.

Depending on the technology used ( FDM, SLA, SLS ), the appropriate material is selected, after which the printer forms the object we have chosen from it in layers. As a rule, plastic, metal, glass, ceramics or wood in the desired form (filament, powder, etc.) is used as the main material, but modern production 3D printers are able to work with many other types of raw materials.

Despite the opportunities that 3D printing opens up for us, it is worth being clearly aware of all the risks associated with this technology.

Shortening of the market chain. If in the case of ordinary goods the market chain includes a producer, one (or several) intermediaries and a consumer, then in the case of 3D products, intermediaries become absolutely unnecessary. In essence, you can directly contact the manufacturer of a particular product to get a 3D model of it and make the desired product yourself. Thus, the number of participants in trade transactions is reduced, and this, in turn, can greatly change the global economy. So far, even experts find it difficult to say whether these changes will be positive, or, on the contrary, will cause the collapse of the economy on a global scale.

So far, even experts find it difficult to say whether these changes will be positive, or, on the contrary, will cause the collapse of the economy on a global scale.

Any product is available to everyone! Sounds like a plus, but it's not that simple. Since in our time many digital products are distributed by the copyright holders themselves absolutely free of charge, it is likely that in the near future the cost of the “information” itself will increase significantly. In other words, you will have to pay for digital data in the same way as now for material ones. At the same time, new types of products can cause a kind of monopoly in the digital market, and only a few companies will dictate their terms/prices.

It is quite obvious that international companies and corporations do not want to allow such a situation, considering not only the possible risks, but also their own interests. As one of the most likely solutions to this problem, intellectual property (roughly speaking, patent and copyright) for 3D products is considered. The meaning of this innovation is that in the event of a product copyright, the manufacturer is forced to pay the copyright holder a part of the cost of the goods. This will solve a number of economic issues, as well as protect the intellectual rights of inventors in the era of 3D technologies.

The meaning of this innovation is that in the event of a product copyright, the manufacturer is forced to pay the copyright holder a part of the cost of the goods. This will solve a number of economic issues, as well as protect the intellectual rights of inventors in the era of 3D technologies.

Today it is difficult to imagine that in the market chain there will be only a producer (or inventor) of a product and a consumer (without any intermediaries), and it is even more difficult to imagine that transnational corporations will put up with such a situation. The only way to protect their rights is through intellectual property, which restricts the free use of their patented technologies. For example, you can take a smartphone: it consists of many parts, for each of which the manufacturing company has a patent. Accordingly, it is impossible to manufacture a new device on your own, violating the interests of copyright holders. The production system associated with 3D printing will work in a similar way.

Many users have a legitimate question: “How exactly will 3D printing interact with the intellectual property system?” And so, a 3D printing object, like any other material product, will have its own evaluation criteria that determine its uniqueness (design, dimensions, shape, technologies and functions used). In the event that identical or too similar products are manufactured, the copyright holder company will be able to use copyright to prohibit the production, import or use of such goods. For serious and intentional copyright infringement, various types of liability will be provided, in particular the payment of a fine or compensation.

Based on the foregoing, it can be assumed that in the near future, many companies and corporations will be forced to think about extending the exclusivity of patents indefinitely. As a result, society may find itself in a position of heavy dependence on the copyright holders of almost any product related to 3D printing.

Order ANET 3D printers from STEPLine!

Masters movement, IP litigation and legal reform

October 2019

Author: Matthew Rimmer * Professor of Intellectual Property and Innovation Law, Department of Law, Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, Australia

3D technology, which is based on the principle of additive manufacturing (as opposed to the principle of subtractive manufacturing, which underlies the traditional manufacturing industry). 3D printing is also associated with the Craftsmen Movement, a social movement whose main idea is to develop designs for various products and share them.

3D printing is also associated with the Craftsmen Movement, a social movement whose main idea is to develop designs for various products and share them.

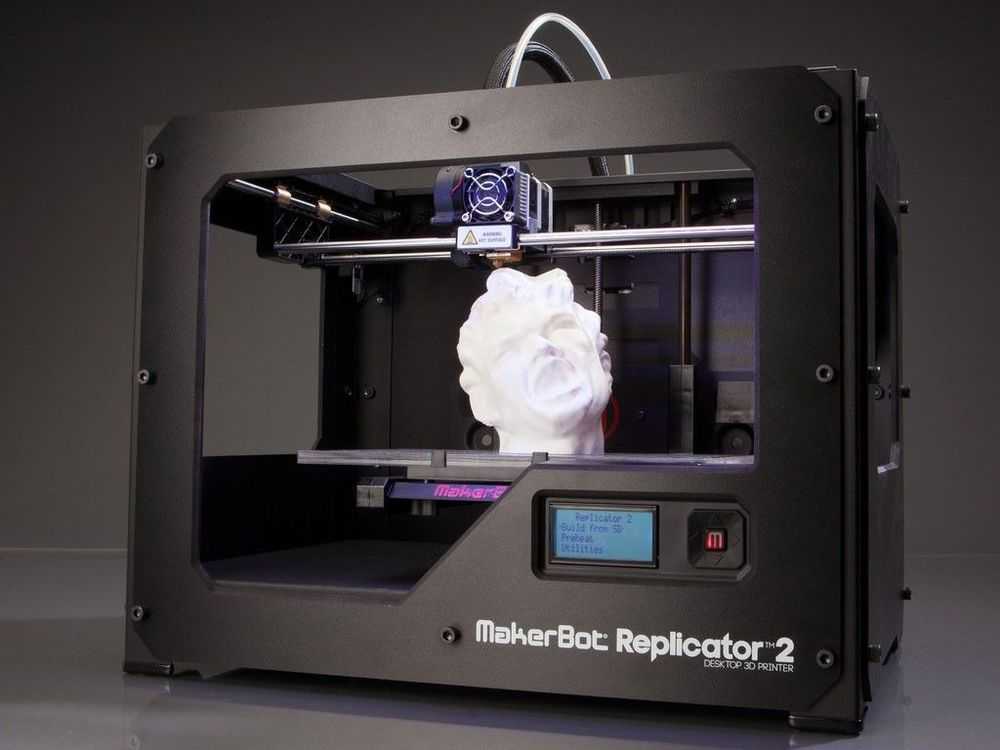

3D printing is currently in transition. The consumer "3D printing revolution", which aimed to have a 3D printer in every home, has failed. MakerBot, a pioneer in 3D printing, is having trouble with its changing approach to intellectual property (IP) issues, disrupting its ties to the open source software community, and the user audience turned away from it. As former MakerBot CEO Bre Pettis said in an interview, "The open source community has kicked us out of their paradise." As a result, MakerBot was acquired by Stratasys, a leader in the 3D printing industry, which restructured and repurposed it.

Some other key players also went bankrupt. In particular, TechShop, a membership-funded and open-to-all network of studio-workshops for home craftsmen, went bankrupt. Maker Media, which publishes Make magazine and hosts craft festivals in the United States, has gone under external control. Make magazine founder Dale Doherty is trying to revitalize his project with a new structure he created called Make Community LLC.

Industrial 3D printing continues to grow

Although personal 3D printing has not developed as expected, there has been growth in a number of other forms and categories of 3D printing. Along with robotics and big data, 3D printing has become one of the promising technologies in the manufacturing industry. Companies specializing in information technology and design are working to improve the way 3D printing is used. Significant investments, especially from transport companies, have been attracted by the technology of 3D printing of metal products. In addition, there have been large-scale experiments related to the application of 3D printing in the healthcare sector, including 3D printing in dentistry, 3D printing in medicine, and bioprinting.

As technology improves and develops, there have been several cases of lawsuits being filed in the courts, as well as certain political developments regarding the regulation of the 3D printing industry. Our recently published book 3D Printing and Beyond explores some of the major developments in IC and 3D printing. In particular, it analyzes the issues of 3D printing in relation to areas such as copyright law, trademark law, patent law, and trade secrets (as well as some of the broader issues related to the regulation of 3D printing). In addition, the book highlights the use of open licensing mechanisms in the field of 3D printing.

3D printing and copyright law

A few years ago, there was a panic that the widespread use of 3D printing would create a wave of large-scale copyright infringements, similar to the situation that arose with the advent of the Napster file-sharing network . Although such fears have not yet materialized, there have been various conflicts related to copyright and 3D printing. For example, Augustana College (United States) objected to 3D scanning of Michelangelo's statues, even though they were not subject to copyright protection and were clearly in the public domain. The American cable television network HBO has blocked the sale of an iPhone stand in the form of an "iron throne" from the TV series "Game of Thrones", made according to the drawings of designer Fernando Sosa using 3D printing. United States singer-songwriter Katy Perry has demanded a ban on the sale of a 3D-printed "shark on the left" figure by the same designer (nevertheless, this product subsequently reappeared in the Shapeways 3D Printing Systems catalog). The heirs of the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp opposed the production of a 3D-printed set of chess pieces based on the works of this artist.

For example, Augustana College (United States) objected to 3D scanning of Michelangelo's statues, even though they were not subject to copyright protection and were clearly in the public domain. The American cable television network HBO has blocked the sale of an iPhone stand in the form of an "iron throne" from the TV series "Game of Thrones", made according to the drawings of designer Fernando Sosa using 3D printing. United States singer-songwriter Katy Perry has demanded a ban on the sale of a 3D-printed "shark on the left" figure by the same designer (nevertheless, this product subsequently reappeared in the Shapeways 3D Printing Systems catalog). The heirs of the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp opposed the production of a 3D-printed set of chess pieces based on the works of this artist.

3D printing was also subject to the on-demand removal of content under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (USA). Shapeways and a number of other 3D printing firms have raised concerns about the implications of this regime for online platforms and 3D printing intermediaries.

Shapeways and a number of other 3D printing firms have raised concerns about the implications of this regime for online platforms and 3D printing intermediaries.

In addition, discussions took place on issues related to the use of technical protection measures in the context of copyright law and 3D printing. For example, the US Copyright Office has confirmed a limited technical protection exception for 3D printing stocks.

3D printing and design law

Developments in 3D printing have also raised the issue of product repair rights.

Efforts have been made in the European Union to recognize the right to repair in order to support consumer rights and develop a circular economy. In this regard, one of the important factors in achieving changes in the behavior of companies and consumers has become the European Greening Directive (Directive 2009/125/EC).

In July 2019, the United States Federal Trade Commission held a Hearing on "Can't be Repaired: A Workshop on Product Repair Restrictions. " Significant differences remain between IP owners and right-to-repair advocates in the United States. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has called for legislation to secure the right to repair for the benefit of farmers in the agricultural regions of the United States.

" Significant differences remain between IP owners and right-to-repair advocates in the United States. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has called for legislation to secure the right to repair for the benefit of farmers in the agricultural regions of the United States.

Significant and first-of-its-kind litigation in Australia regarding right to repair under industrial design law ( GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S . . - S - Auto Parts Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 97). The Australian Treasury is considering policy options regarding the practice of sharing vehicle repair information.

Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Consumer Affairs Minister Shane Rettenbury called for recognition of the right to repair from the rostrum of the Consumer Affairs Forum, which includes ministers from both Australia and New Zealand. Federal Minister Michael Succar asked the Australian Productivity Commission to look into the matter.

Federal Minister Michael Succar asked the Australian Productivity Commission to look into the matter.

Calls for right-to-repair laws, both at the provincial and federal levels, are also being heard in Canada. As Laura Tribe, Executive Director of Open Media, noted in this regard, “We are committed to ensuring that people have the opportunity to be the real owners of the products they own.”

3D printing and trademark law

3D printing also brings uncertainty to trademark law and related legal regimes, including product substitution, identity rights, commercial use of characters, and trade dress. The legal conflict surrounding Katy Perry's trademark application for the "shark on the left" image provides some insight into some of the issues that arise in this regard.

Regarding bioprinting, Advanced Solutions Life Sciences sued Biobots Inc. In connection with the alleged violation of its trademark rights ( Advanced Solutions Life Sciences , LLC V . Advanced Solutions Life Sciences owns and uses the registered trademark Bioassemblybot for 3D bioprinting and tissue growth.

Advanced Solutions Life Sciences owns and uses the registered trademark Bioassemblybot for 3D bioprinting and tissue growth.

3D printing and patent law

According to the 2015 WIPO Global Intellectual Property Report "Breakthrough Innovation and Economic Growth", 3D printing patent filings are on the rise. Some industrial 3D printing companies, including 3D Systems and Stratasys, have managed to build large 3D printing patent portfolios. Large industrial companies, including GE and Siemens, have also accumulated significant patent assets in 3D printing and additive manufacturing. Information technology companies, including Hewlett Packard and Autodesk, also play an important role in the 3D printing industry.

With the growing commercial importance of 3D printing in the manufacturing industry, there have been a significant number of litigations related to 3D printing of metal products. In July 2018, as part of the “Desktop Metal Inc.” v. Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018 Case No. 1:18-CV-10524), a federal jury found that Markforged Inc. did not infringe two patents owned by rival Desktop Metal Inc. (See Desktop Metal Inc. v. Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018) 2018 WL 4007724 (Massachusetts District Court, jury verdict). In this regard, the CEO of Markforged Inc. .” Greg Mark stated, “We are pleased with the jury's verdict that we have not infringed patents and that Metal X technology, which is the latest addition to the Markforged 3D printing platform, is based on our own Markforged's proprietary designs." For its part, a spokesman for Desktop Metal noted that it was "satisfied that the jury recognized the validity of all claims in both Desktop Metal patents, which were discussed in a lawsuit against the company "Markforged"

1:18-CV-10524), a federal jury found that Markforged Inc. did not infringe two patents owned by rival Desktop Metal Inc. (See Desktop Metal Inc. v. Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018) 2018 WL 4007724 (Massachusetts District Court, jury verdict). In this regard, the CEO of Markforged Inc. .” Greg Mark stated, “We are pleased with the jury's verdict that we have not infringed patents and that Metal X technology, which is the latest addition to the Markforged 3D printing platform, is based on our own Markforged's proprietary designs." For its part, a spokesman for Desktop Metal noted that it was "satisfied that the jury recognized the validity of all claims in both Desktop Metal patents, which were discussed in a lawsuit against the company "Markforged"

In 2018 (after the above verdict) Desktop Metal Inc. and Markforged Inc. entered into a confidential financial agreement that settled all other litigation between them. However, in 2019 Markforged Inc. filed another lawsuit against Desktop Metal Inc. due to the fact that, according to her, the latter violated that part of the agreement, which concerned non-disclosure of negative information.

due to the fact that, according to her, the latter violated that part of the agreement, which concerned non-disclosure of negative information.

3D printing and trade secrets

In addition, the first litigation regarding 3D printing and trade secret legislation took place. In 2016, Florida-based 3D printing startup Magic Leap filed a lawsuit in federal court for the Northern District of California against two of its former employees for misappropriation of trade secret information within the meaning of Trade Secret Protection Act (“ Magic Leap Inc ." v Bradski et al (2017) case no. 5:16-cvb-02852). In early 2017, a judge granted the defendants' request to stay the case, stating that Magic Leap had failed to provide "a reasonable degree of specificity" to the disclosure of alleged trade secrets. Subsequently, the judge allowed Magic Leap to amend the text of its submission. In August 2017, the parties entered into a “confidential agreement” in connection with this issue. In 2019Mafic Leap sued the founder of Nreal for breach of contract, fraud, and unfair competition (Magic Leap Inc. v. Xu, 19-cv-03445, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (San Francisco)).

In 2019Mafic Leap sued the founder of Nreal for breach of contract, fraud, and unfair competition (Magic Leap Inc. v. Xu, 19-cv-03445, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (San Francisco)).

3D printing and open licensing

In addition to proprietary IP protections, 3D printing has a widespread practice of open licensing. Companies with a free distribution philosophy include Prusa Research (Czech Republic), Shapeways (Netherlands-US) and Ultimaker (Netherlands). Members of the Craft Movement used open licensing mechanisms to share and distribute 3D printing files. As noted in The State of the Commons 2017, the Thingiverse platform was one of the most popular platforms using Creative Commons licenses.

Other issues arising from the development of 3D printing

In addition to IP issues, the development of 3D printing also raises a number of other legal, ethical and regulatory issues. In healthcare, regulators have faced challenges with personalized medicine. The United States Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Health Products Administration held consultations on the development of a balanced set of regulations for medical 3D printing and bioprinting. The European Parliament has adopted a resolution calling for a comprehensive approach to the regulation of 3D printing.

In healthcare, regulators have faced challenges with personalized medicine. The United States Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Health Products Administration held consultations on the development of a balanced set of regulations for medical 3D printing and bioprinting. The European Parliament has adopted a resolution calling for a comprehensive approach to the regulation of 3D printing.

Litigation regarding 3D printing of firearms is also ongoing in the United States. Several state attorneys general have sued the current administration to obstruct an agreement between the federal government and Defense Distributed. Several criminal cases have been filed in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and Japan in connection with attempts to 3D print firearms. Legislators are debating the feasibility of criminalizing crimes related to possession of digital blueprints for 3D printed firearms.

Footnotes

* Dr. Matthew Rimmer is Head of the KTU Research Program on Intellectual Property Law and Innovation and is also involved in the KTU Electronic Media Research Center, the KTU Australian Health Law Research Center and the KTU International Law Research Program and global governance.