Cost to print a 3d gun

The 3D-printed semi-automatic rifle is now a reality.

The FGC-9 is a 100 percent homemade semi-automatic rifle. CTRLPew/YouTubeOn Jan. 1, Chase Tkach—chair of the Orleans County, New York, Libertarian Party, also known as porn actor Molly Smash—uploaded two fast-flashing, dubstep-tuned theatrical trailers to their Pornhub channel. The videos were promoting cheap, untraceable, 3D-printed, plastic, DIY, semi-automatic guns. That’s because Tkach likes guns, specifically unregulated ones. And homemade guns are so hot right now.

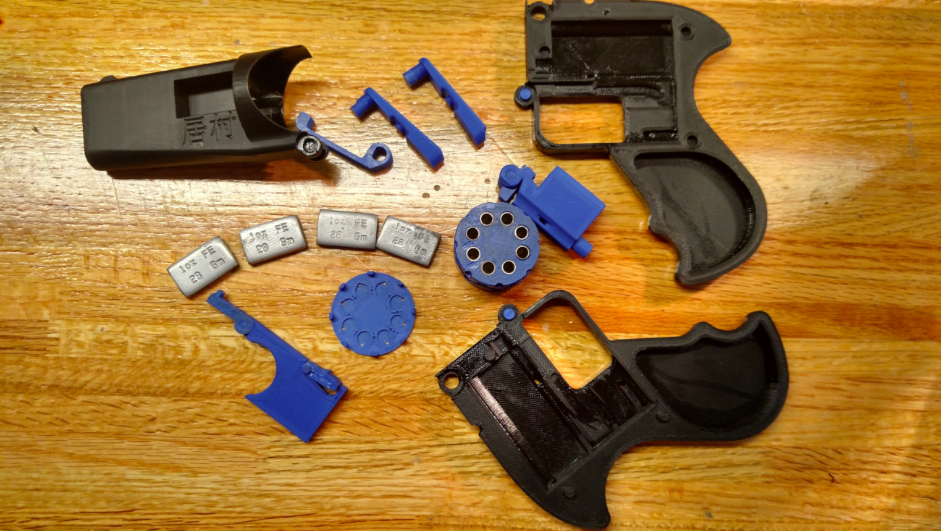

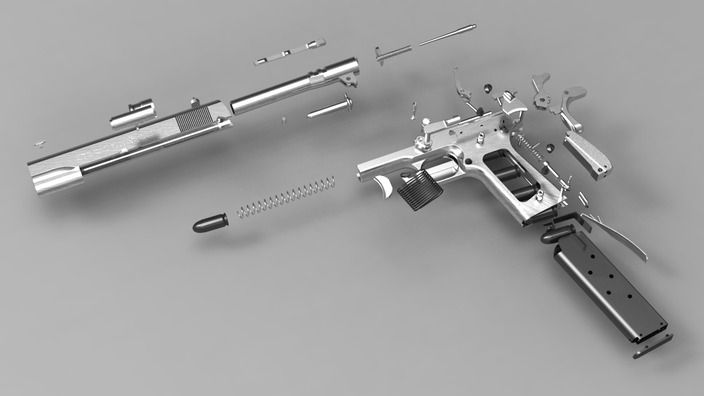

People have been making 3D-printed guns at home since 2013. They used to be pretty low-tech, capable of one shot before busting. But they’ve come a long way in the past few years. Now you can print untraceable AR-15s, AKMs, semi-automatic pistols, and more—no serial number, no registration, no background check. Up until recently, however, the best you could do with a semi-automatic rifle like the AR-15 was 3D-print the lower receiver (the core part that’s regulated as a firearm). Users still had to buy real magazines, triggers, and barrels to complete the kit and build a working gun. That’s easy to do if you live in America, where most people can purchase gun parts (minus the receiver) online. But it’s a problem if you live in a country with strict gun control like Germany, where most people can’t easily purchase the necessary parts.

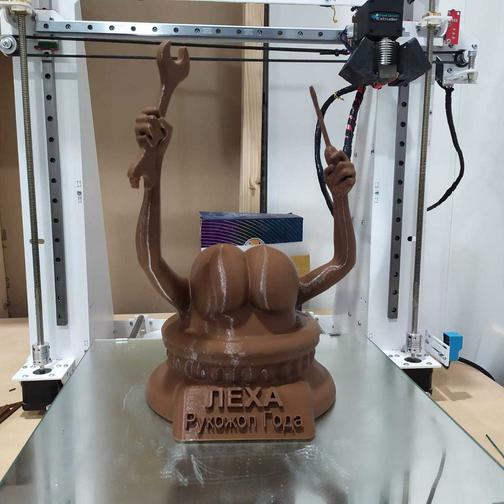

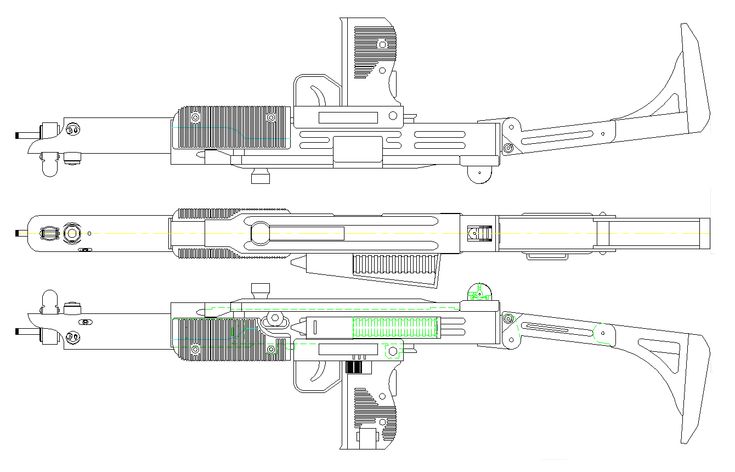

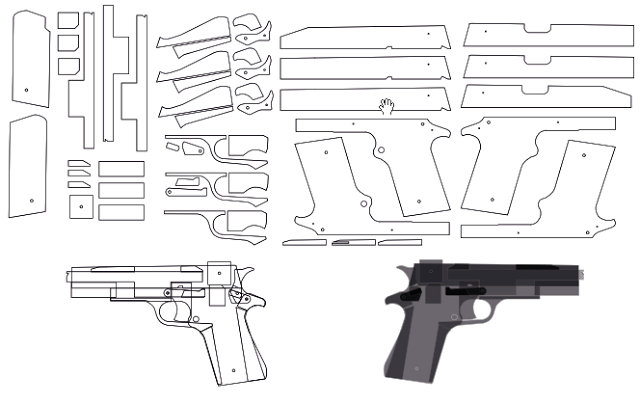

All that changed in March, when 3D-printing and firearm enthusiasts publicly released the design for a 100 percent homemade semi-automatic rifle that not only shoots 9 mm ammo exceptionally well but is durable enough to withstand thousands of rounds. They called it the FGC-9, which stands for “fuck gun control 9 mm. ” Most of the gun is 3D-printed, while the rest includes inconspicuous parts available at hardware stores. The files include detailed instructions to help anyone—even if they don’t have technical knowledge—build their own. They explain which 3D printer to buy, how to cast DIY ammo at home, and how to modify a metal tube in your bedroom to turn it into a gun barrel. The metal means the gun can’t sneak past metal detectors, but it also means there are no consequences for owning one in the U.S. 3D-printed guns are legal, as long as they can be picked up by a metal detector.

” Most of the gun is 3D-printed, while the rest includes inconspicuous parts available at hardware stores. The files include detailed instructions to help anyone—even if they don’t have technical knowledge—build their own. They explain which 3D printer to buy, how to cast DIY ammo at home, and how to modify a metal tube in your bedroom to turn it into a gun barrel. The metal means the gun can’t sneak past metal detectors, but it also means there are no consequences for owning one in the U.S. 3D-printed guns are legal, as long as they can be picked up by a metal detector.

If you already have a 3D printer (the recommended one is about $250) and basic hand tools, it costs about $100 for the rest of the tools to build the barrel, then about $100 in supplies for each gun after that. For reference, a Smith & Wesson M&P15 Sport (a popular midtier AR-15-style rifle) starts at about $750 off the shelf. A technically inclined builder could make an FGC-9 in less than a week. Someone with no experience could possibly learn everything they need and build it in a couple of weeks.

A technically inclined builder could make an FGC-9 in less than a week. Someone with no experience could possibly learn everything they need and build it in a couple of weeks.

The videos Tkach uploaded to Pornhub were cut by Alex Holladay, who has been producing content for Deterrence Dispensed, a big group chat administered by a few design collaborators including the designers of the FGC-9—an anonymous European who goes by JStark or Jacob and an American using the moniker Ivan the Troll. Jacob was the driving force behind the development of the FGC-9 and was featured in British journalist Jake Hanrahan’s short documentary Plastic Defence. Ivan, who designed the barrel and magazine for the FGC-9, is sometimes called the spokesperson of Deterrence Dispensed and has been interviewed about his gun designs in Wired and the New Republic. They are active figures in the user-made firearm subreddit, though not without pushback from the platform: Ivan has been suspended from Reddit several times and says he has lost count of how many profiles he has gone through, though he thinks it’s more than 10. He was also suspended from Twitter in 2019 after Sen. Robert Menendez of New Jersey, an opponent of the free distribution of 3D-printable-gun blueprints, wrote a letter to Twitter urging the platform to ban Ivan. He has since returned under a new handle.

He was also suspended from Twitter in 2019 after Sen. Robert Menendez of New Jersey, an opponent of the free distribution of 3D-printable-gun blueprints, wrote a letter to Twitter urging the platform to ban Ivan. He has since returned under a new handle.

I was able to verify Ivan’s actual identity and reach him for a phone call. He did not want his real name used because he says he has received death threats on social media and doesn’t want those reaching his family, so I will continue to refer to him by the pseudonym Ivan.

He’s 23 years old, graduated from college in 2020 with a degree in computer science, and lives with his parents in Southern Illinois. From the front, their house looks like any unassuming gray suburban home. Out back, his family has about 50 acres of fields and woods, where Ivan has a shooting range; inside, he has an entire room dedicated to designing and printing guns. He grew up in a gun-friendly Midwestern family and was introduced to 3D printing in a high school class.

He grew up in a gun-friendly Midwestern family and was introduced to 3D printing in a high school class.

He didn’t have gunsmithing in mind when he bought his first printer. He drives a 30-year-old car and wanted to make plastic parts to spruce up the interior trim. The gun printing started a few years later, when he read online about people printing AR-15 lower receivers. It took him about five tries to get one to turn out right, and it lasted him more than 2,000 rounds. That inspired him to pursue 3D-printable-gun development to push the technology forward. He jumped into what he calls the “social media boom” of 2018, by which he means 2018 was the year 3D-printed guns broke out of niche circles and grew a sizable following online. It was when the infamous 3D-printed gun designer and now registered sex offender Cody Wilson of Defense Distributed (to which the name Deterrence Dispensed is a cheeky tribute) settled his lawsuit against the U. S. government affirming arguments that 3D-printable-gun files could be sharable as free speech without regulation.

S. government affirming arguments that 3D-printable-gun files could be sharable as free speech without regulation.

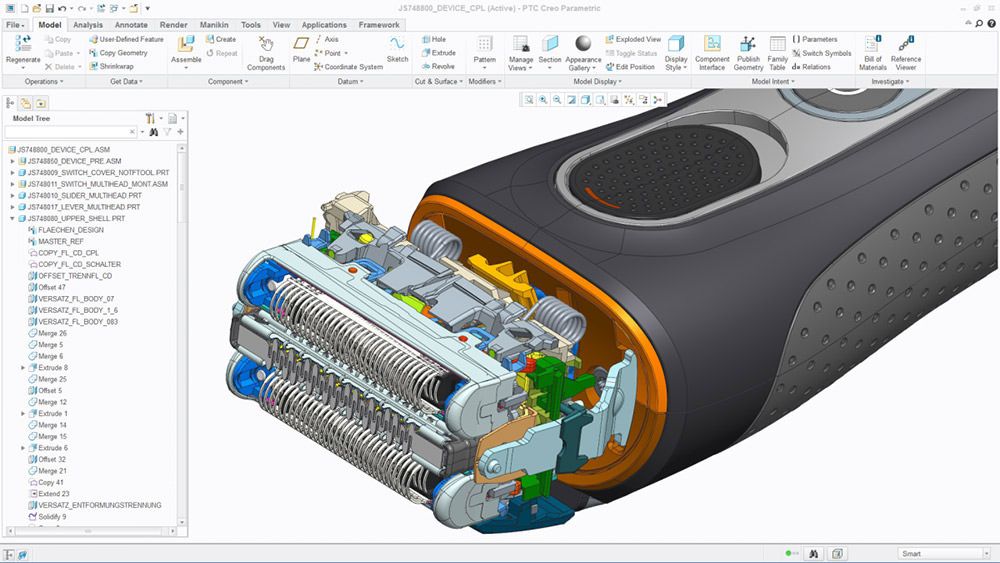

Ivan says his first time communicating with Jacob was on Reddit and Twitter, where they ran in the same crowds of homemade gun designers. Jacob recruited Ivan to teach him computer-aided drafting software so he could design what would ultimately become the FGC-9. Since then, they’ve worked together on a few builds, but Ivan says they still don’t know each other’s real identities.

Up until mid-January, Deterrence Dispensed operated on the encrypted chat platform Keybase—recently acquired by Zoom—where it grew to almost 27,000 members, though Ivan says only a few thousand were actively participating. At the beginning of the year, Keybase informed Ivan that the group would be shut down. In an email to me, a Keybase spokesperson said Keybase’s Acceptable Use Policy was updated following Zoom’s acquisition, and the company determined Deterrence Dispensed was no longer in compliance. The policy prohibits content involving weapons and instructions on making weapons. On Jan. 20, the Keybase group was locked, and Deterrence Dispensed moved to a new self-hosted chat platform. But Ivan says they were prepared for the move—they knew that Keybase was changing its policy—most of the active users have joined the new chat, and participation is continuing uninhibited.

In an email to me, a Keybase spokesperson said Keybase’s Acceptable Use Policy was updated following Zoom’s acquisition, and the company determined Deterrence Dispensed was no longer in compliance. The policy prohibits content involving weapons and instructions on making weapons. On Jan. 20, the Keybase group was locked, and Deterrence Dispensed moved to a new self-hosted chat platform. But Ivan says they were prepared for the move—they knew that Keybase was changing its policy—most of the active users have joined the new chat, and participation is continuing uninhibited.

The goal of the chat is to build a collaborative community of designers and enthusiasts not only to advance home gunsmithing methods but also to get these guns into the hands of anyone who wants one. Ivan says the goal isn’t to make sure everyone has a gun but rather to make sure everyone has the technical capability to decide to have a gun. He is a proponent of gun freedom and believes citizens should have arms to defend and fight against tyranny. Ivan says the group has a romantic fantasy that their designs will reach oppressed groups, like Uighurs, who are facing genocide in China. But the designs are also favored by far-right extremists in the U.S., including those in the Boogaloo movement, who may want untraceable firearms to evade law enforcement, according to Wired.

He is a proponent of gun freedom and believes citizens should have arms to defend and fight against tyranny. Ivan says the group has a romantic fantasy that their designs will reach oppressed groups, like Uighurs, who are facing genocide in China. But the designs are also favored by far-right extremists in the U.S., including those in the Boogaloo movement, who may want untraceable firearms to evade law enforcement, according to Wired.

The release of the FGC-9, a major milestone for the Deterrence Dispensed coalition, was an improvement on a model called the AP-9 by an anonymous designer who goes by Derwood. The AP-9 uses a Glock barrel and magazine. But Ivan built a 3D-printed version of the magazine that uses a coiled metal spring. And he designed a homemade barrel by carving spiral grooves—the rifling that makes the bullet spin—inside a metal tube using electrochemical machining, which may sound complicated, but it’s a relatively simple DIY solution to etch steel using saltwater, electricity, and copper wire twisted around a 3D-printed mandrel. Deterrence Dispensed has a full tutorial (which I am not going to link to). The hardware has been converted to metric, to make it buildable outside the U.S.

Deterrence Dispensed has a full tutorial (which I am not going to link to). The hardware has been converted to metric, to make it buildable outside the U.S.

Ivan tells me the FGC-9 is the easiest, cheapest, most accessible, and reliable semi-automatic DIY firearm that he is aware of. It shows that it’s possible to build highly effective semi-automatic rifles with common tools. It certainly takes more work than going to Cabela’s to buy a gun in the U.S., but it’s easy enough that anyone who wants a gun and has the motivation to learn can build one at home while thousands of people online guide them through the process. It’s hard to imagine stopping it, short of banning 3D printers or metal pipes. Even regulating the distribution of the designs wouldn’t do much. The designs are distributed using a blockchain, so there’s no central server to take down. And the FGC-9 designs have already been viewed more than 44,000 times just on the original site they were uploaded to—they have been replicated elsewhere, for who knows how many people.

And the FGC-9 designs have already been viewed more than 44,000 times just on the original site they were uploaded to—they have been replicated elsewhere, for who knows how many people.

It’s a volatile time for gun owners in America. On Feb. 14, the third anniversary of the Parkland school shooting, President Joe Biden called on Congress to pass stricter gun control, including a ban on assault weapons. The future of firearms in the U.S. may be one where assault weapons can only be obtained by purchasing them on the black market or building them at home. The latter is now a viable option.

- You’re Not Going to Like How Colleges Respond to That Chatbot That Writes Papers

- Big Tech Is Getting Its Reward

- What Is COVID Actually Doing to Our Immune Systems?

- What I Learned After Three Beers at a Bitcoin Bar

There’s an ethical question that comes up in writing this story—whether I’m giving Deterrence Dispensed a platform, potentially leading more people to a dangerous movement. But Ivan and his team already have a huge platform, making critical coverage ever more important. The hype is spreading, and not just on Pornhub and Reddit. The FGC-9 has been discussed on neo-Nazi forums on the dark web. Deterrence Dispensed has been featured in gun podcasts. And users on TikTok are teaching one another how to build rifles at home with some videos reaching millions of views. It’s happening, whether or not journalists like me cover it—and because it’s happening, people need to know about it.

“There is no sign of things stopping. Projects are only getting more ambitious,” Ivan says. The group is currently working on a second-generation FGC-9. Ivan says it will make the barrel and bolt manufacturing easier, and improves the ergonomics and appearance of the gun. It’s close to ready, they just need to finish documentation and a few minor details. They expect to release the designs to the public in the next few months.

Ivan says it will make the barrel and bolt manufacturing easier, and improves the ergonomics and appearance of the gun. It’s close to ready, they just need to finish documentation and a few minor details. They expect to release the designs to the public in the next few months.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

- Crime

- Gun Control

- Guns

I 3D-Printed a Glock to See How Far Homemade Weapons Have Come

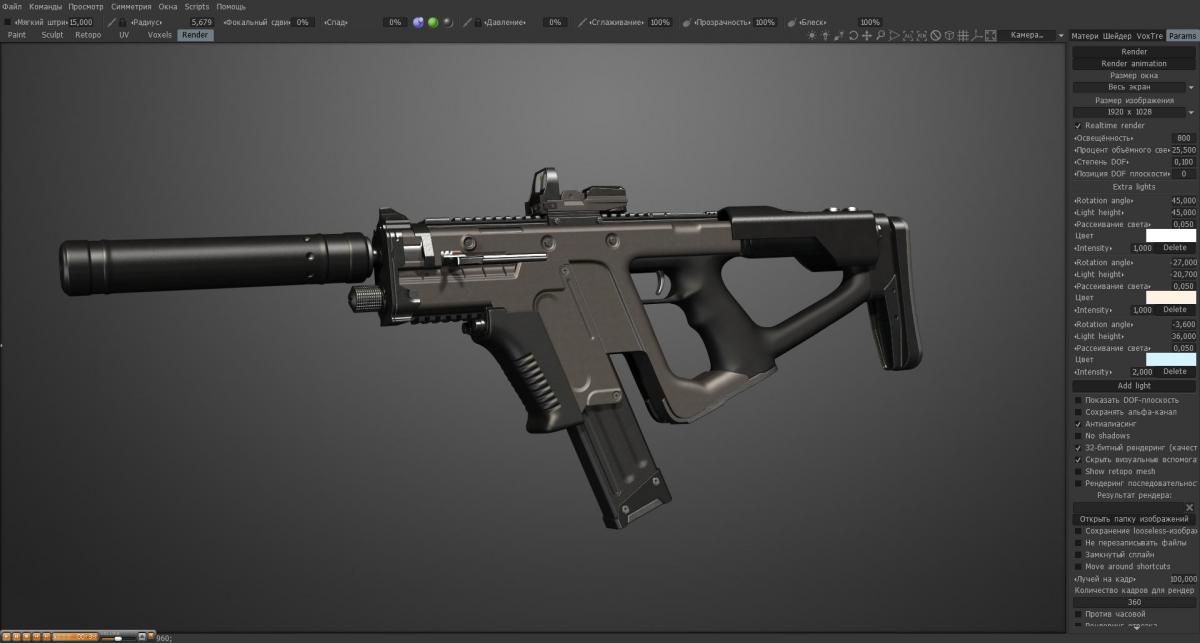

ST. AUGUSTINE, Florida — The fully-automatic “Scorpion” submachine gun can burn through a 30-round clip of 9mm ammo in a matter of seconds with one steady pull of the trigger. It looks, feels, and shoots just like a factory-made gun—except part of this one came off a 3D printer.

It looks, feels, and shoots just like a factory-made gun—except part of this one came off a 3D printer.

According to the Scorpion’s maker, the material used to 3D-print the frame (the heart of the gun, where the metal barrel and other parts all come together) is actually “on par or stronger” than the off-the-shelf equivalent. I’d never fired a full-auto weapon before—let alone one made partly of plastic—and when I took aim and squeezed the trigger, the Scorpion unleashed a wild spray of bullets that missed my target and thumped into a mound of dirt behind the firing range.

Advertisement

The Scorpion was one of many jaw-dropping weapons on display in late June at a Florida event dubbed the “Gun Maker’s Match,” the first-ever shooting competition exclusively for home-assembled firearms. Except for the machine gun, which requires a special federal license, these are a species of “ghost gun,” meaning there are no serial numbers and thus no easy way for authorities to track down the owner or manufacturer.

The shooting contest was put on by a non-profit called Guns For Everyone National, with help from the digital gun building collective Are We Cool Yet? or AWCY, which has been pushing the envelope of what’s possible with 3D-printed arms.

To meet these gunmakers and get a true sense of what 3D-printed guns are capable of these days, I decided to enter the shooting contest in Florida—and build my own ghost gun.

Although the technology has radically evolved in recent years, the best-known 3D-printed gun is still The Liberator, the first one ever created, in 2013. A single-shot, snub-nose pistol, The Liberator resembled a postmodern “Saturday night special,” something just as likely to blow your hand off as fire an actual bullet. These days, beyond the Scorpion, AWCY has created and released plans for a 3D-printed “battle rifle” and under-barrel flare guns that are just a few millimeters away from the military’s “RAMBO” model 3D-printed grenade launcher.

Advertisement

News

People Are Panic-Buying Untraceable ‘Ghost Guns’ Online in the Coronavirus Pandemic

Tess Owen

The most common and controversial ghost guns cost a few hundred dollars online and come “80 percent” finished in a box with all the necessary tools. The sudden proliferation of these cheap, mail-order ghost guns has prompted alarm among law enforcement nationwide. Nearly 24,000 “privately made firearms” were recovered at crime scenes from 2016 to 2020, according to a recently leaked Department of Justice report, and the number of cases where felons and other “prohibited persons” were found with such guns doubled in a single year.

Ghost guns have also turned up in the hands of white supremacists and far-right extremists. A self-proclaimed Boogaloo Boi pleaded guilty last month to possession of 3D-printed machine gun parts and a homemade silencer. The DOJ report, issued June 22 and verified by The Trace, warned of individuals with “racially or ethnically motivated violent extremist ideologies” sharing 3D-printed machine gun files.

Advertisement

To meet these gunmakers and get a true sense of what 3D-printed guns are capable of these days, I decided to enter the shooting contest in Florida—and build my own ghost gun.

Only ten states plus Washington, DC, have local laws that attempt to regulate ghost guns. They are virtually unregulated federally, but the Biden administration has proposed new rules that would require serial numbers on certain unfinished parts and restrict mail-order kits, which the president singled out in an April speech at the White House.

“The buyers aren’t required to pass a background check to buy the kit to make the gun,” President Joe Biden said. “Consequently, anyone from a criminal to a terrorist can buy this kit and, in as little as 30 minutes, put together a weapon.”

But building a 3D-printed gun from scratch, as I learned, takes a lot longer than half an hour. And while there’s evidence of extremists and criminals seeking to exploit the untraceability of ghost guns, there is also a nerdy group of designers and tinkerers who insist they are strictly abiding by gun laws and enjoying a “very loud” hobby.

Shopping for the Ghost Gun

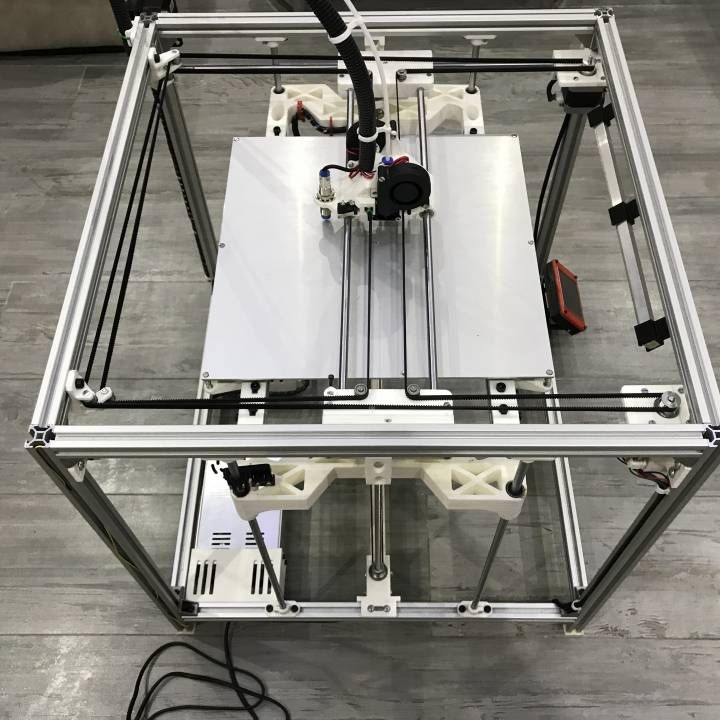

Having never owned a 3D-printer or a gun, I started as a blank slate. Rob Pincus, a personal defense instructor and gun rights advocate, agreed to lend expertise and a 3D-printer. He warned the printing and building process would take at least two days, which he said contradicts the notion that it’s easy for people who want to misuse guns to simply 3D-print one.

Rob Pincus, a personal defense instructor and gun rights advocate, agreed to lend expertise and a 3D-printer. He warned the printing and building process would take at least two days, which he said contradicts the notion that it’s easy for people who want to misuse guns to simply 3D-print one.

“You have to want to do it this way,” Pincus said. “I don't know who the person is that falls into the weird zone where they don't want to buy a gun, they can't buy a gun, but they really want a gun and this is the path of least resistance, as opposed to finding somebody to buy a gun for them or buying a gun illegally out of somebody's trunk somewhere.”

Advertisement

My initial aim was to build AWCY’s Scorpion, which can be legally 3D-printed and assembled in semi-auto (one bullet per trigger squeeze) in most places. But Pincus dashed my Scorpion dreams.

For one thing, it takes multiple days of 3D-printing to make one, which was time I didn’t have before the match. There’s also a shortage of ghost gun parts on the internet—in part due to a recent buying spree amid the Biden’s administration efforts to tighten the laws.

Without metal parts, the Scorpion would not work. While 3D-printed plastic is strong enough to serve as the frame of the gun, it won’t hold up as a barrel or bolt. It would also be illegal, since federal law requires guns to have at least one metal component.

The author's 3D-printed Glock 19 9mm pistol with the words "Ghost Gun" on the grip. (Photo by Keegan Hamilton / VICE News)

“You need the metal parts,” Pincus told me. “Technically, could you build one out of all plastic? Yes. Is it going to be reliable and awesome? Probably not.”

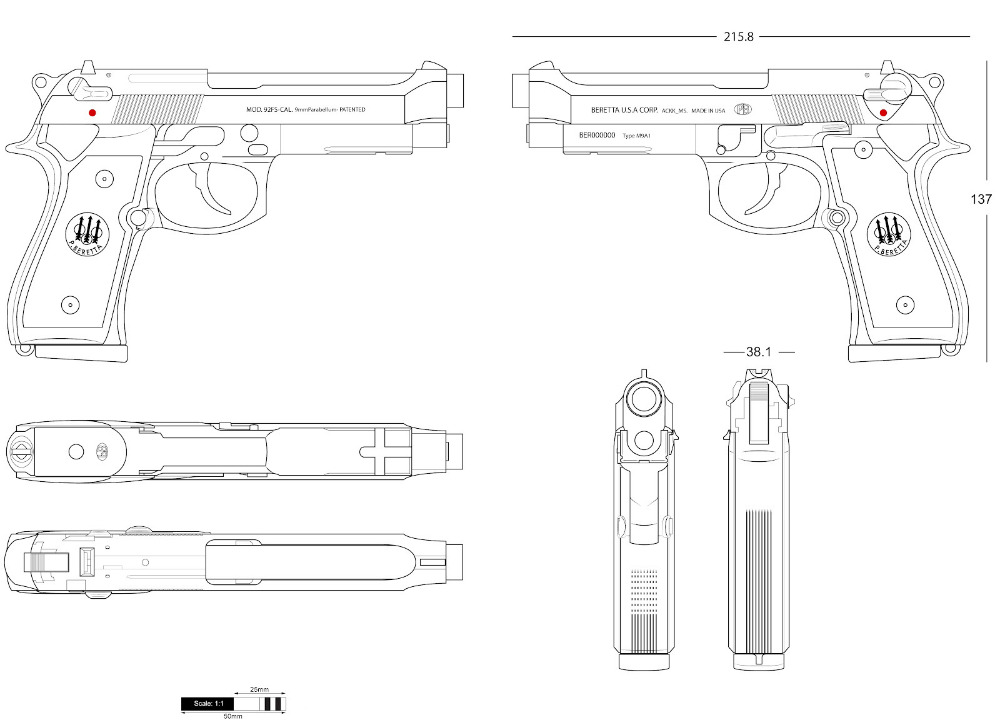

I ultimately settled on the Glock 19, as its essential parts were readily available online. The barrel, slide, trigger assembly, and other metal bits cost around $320, shipped directly to the gun range in Florida hosting the match, along with a $23 spool of PLA+ filament. That plus a standard 3D-printer and a couple boxes of 9mm ammo was almost all I needed.

Printing the Gun

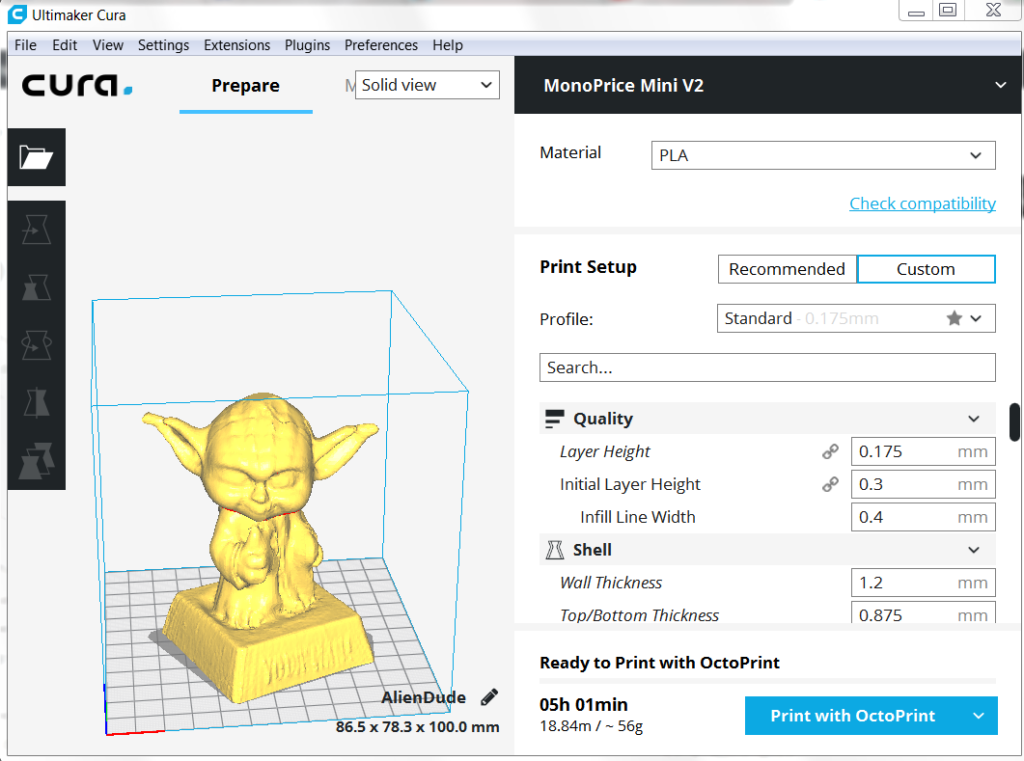

The Glock design, along with plans for hundreds of other guns, is accessible through a website called DEFCAD. It’s hosted by a company called Defense Distributed, led by Cody Wilson, inventor of the first 3D-printed gun. The files can be found elsewhere online, but Wilson’s site makes the repository easy to browse in a store-like user interface, and users must pay a $50 annual membership for access.

It’s hosted by a company called Defense Distributed, led by Cody Wilson, inventor of the first 3D-printed gun. The files can be found elsewhere online, but Wilson’s site makes the repository easy to browse in a store-like user interface, and users must pay a $50 annual membership for access.

For years, the U.S. government tried to limit sharing of 3D-printed gun blueprints through the State Department’s powers over international arms exports. Wilson fought back on First Amendment grounds, and in April the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling that indefinitely lifted restrictions on publishing 3D-printed gun blueprints.

Advertisement

When I asked Wilson if U.S. authorities could ever hope to totally block the files from being shared online, he replied: “The government should invent a time machine and kill me seven years ago. It's far too late now. The equipment—the 3D printing, it's so cheap. You can make anything. You can design anything.”

For years, the U.

S. government tried to limit sharing of 3D-printed gun blueprints through the State Department’s powers over international arms exports.

Wilson is a polarizing figure in the gun world. In 2018, he was arrested and accused of sexually assaulting a 16-year-old girl he met through SugarDaddyMeet.com. He pleaded guilty to injuring a child, a third-degree felony, and received seven years of probation. In addition to hosting 3D-gun files, Wilson also sells a machine called The Ghost Gunner, which helps convert unfinished parts into AR-15s and other guns.

“The files are literally everywhere in a perfect fluid explosion on the internet,” Wilson said. “It's not supposed to be legal, and yet we found a way to make it legal.”

To get the files from Wilson’s site, I had to verify my identity and sign up for a membership, bringing the total gun budget to just under $400, still cheaper than a brand-new Glock. But when my frame came off the printer (a 16-hour process), there were a few glaring differences. For one, mine did not have a serial number; instead it had the words “Ghost Gun” literally printed on the handle. It was also rough around the edges, not yet ready for the metal parts to be inserted.

For one, mine did not have a serial number; instead it had the words “Ghost Gun” literally printed on the handle. It was also rough around the edges, not yet ready for the metal parts to be inserted.

Advertisement

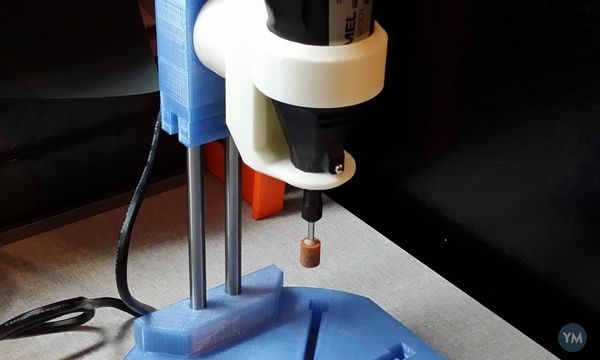

It took another four hours and change to sand down the plastic using metal filing tools, a drill, and an electric Dremel grinder. Pincus patiently guided me as I stumbled through the process, which was harder than it seemed on the instructional videos I’d seen on YouTube. The finished product was white on the bottom (my “Ghost Gun”-emblazoned frame) and black on top, with a factory-made barrel and slide. Pincus assured me it was safe to test fire.

Shooting the Ghost Glock

On the shooting range, the plastic ghost Glock felt heavy in my hand. There are videos of 3D-printed guns splintering into pieces during test fires, and I was a little nervous as Pincus coached me on posture and grip. I squeezed the trigger and the first round pinged off a metal target 15 yards away. The gun worked, but not perfectly. All the grinding to make the metal parts fit together caused a jamming issue. More work with the Dremel tool helped, and after several more test fires, Pincus deemed the gun ready for competition.

The gun worked, but not perfectly. All the grinding to make the metal parts fit together caused a jamming issue. More work with the Dremel tool helped, and after several more test fires, Pincus deemed the gun ready for competition.

The match in Florida drew around 50 entrants, almost exclusively white and male, with a couple dressed in full-camo. The mood was more carnival than militia gathering, with everyone gawking at each other’s guns and some online-only friends meeting face to face for the first time. There were multiple contest categories, ranging from kit guns to weapons entirely 3D-printed with homemade metal components. Contestants were judged on a combination of speed and accuracy, maneuvering through courses and shooting at stationary targets.

Advertisement

“This is really what we want to be the first of many celebrations of what I call a freedom hobby,” Pincus said, addressing the crowd. “For some of us, it's, ‘Hey, I want to make my own gun. I don’t want the government involved. ’ For some of us, it's ‘I want a custom gun that has my logo or my name or my grip angle or whatever’... for other people, it's, ‘I want to create designs that never existed before and share them with all of Earth.’”

’ For some of us, it's ‘I want a custom gun that has my logo or my name or my grip angle or whatever’... for other people, it's, ‘I want to create designs that never existed before and share them with all of Earth.’”

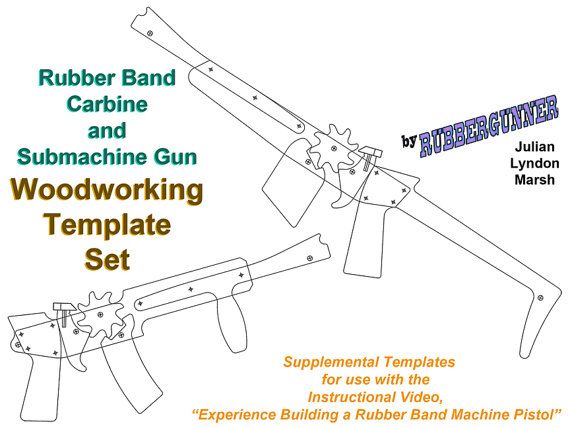

Leading the push to create wholly unique 3D-gun designs is Darren “Derwood” Booth, a chain-smoking West Virginian who told me he likes living in a rural area because he can step out his front door and test-fire new designs whenever he pleases. His latest work is called the King Cobra, which is virtually indistinguishable to the untrained eye from a factory-made assault weapon. A 9mm “pistol caliber carbine” like the Scorpion, the King Cobra is totally original and homemade, emblazoned with a skull and lightning-bolts symbol Derwood borrowed from Quentin Tarantino’s film “Death Proof.”

Rob Pincus (right) and Xander Guetzloe, a moderator of the group Are We Cool Yet?, address the crowd at the "Gun Maker's Match" shooting competition in Florida in June 2021. (Photo by Keegan Hamilton / VICE News)

Derwood posts his files online for anyone to download or modify, and says he does not profit from his work. “I haven’t ever made a dime off of it,” he told me. “I've invested thousands just in the hobby, but no, I haven't made a red cent.”

“I haven’t ever made a dime off of it,” he told me. “I've invested thousands just in the hobby, but no, I haven't made a red cent.”

Derwood’s designs are showing up all over the world, including in countries where 3D-printing now threatens to undermine strict gun control laws. His work was the basis for another “pistol caliber carbine” called the FGC-9 (short for Fuck Gun Control 9mm), wielded last year by an anonymous masked man in a documentary about the rise of 3D-printed guns in Europe.

Advertisement

“I’m not so happy with that,” Derwood said. “Because, hey, they have laws over there. Obey your local laws. I’m not encouraging anybody to do anything illegal.”

Art That Can Kill

Some plastic gunsmiths argue their work is shielded not only by the right to bear arms but also the First Amendment’s right to freedom of expression, since their guns are works of art. The group AWCY, which organized the Florida shooting contest, handed out stickers with the silhouette of their 9mm Scorpion and the motto “Art is not meant to be contained. ”

”

Xander Guetzloe, a moderator for AWCY, brought a Scorpion to the Florida match that he modified to make it look like the barrel spits fire from a dragon’s mouth.

“Art is in the eye of the beholder, right? This is just a way of expressing ourselves,” Guetzloe said. “It's freedom of expression in a much louder way.”

Guetzloe estimated that AWCY has about 500 members, with 200 actively working on gun design projects in the group’s online forum. The members, he said, include “lawyers, technical writers, plumbers, electricians, just a little bit of everybody,” each lending their own expertise.

AWCY’s aesthetic is vaguely hipster and intentionally low-brow, with guns modified to look extra phallic or with Nerf-style neon colors. They tease new 3D-gun file releases on a well-curated Instagram feed, often finding inspiration in classic weapons that have cult followings. Guetzloe, who has a day job in IT, worked on creating a 3D-printed CETME, a “battle rifle” that’s seen combat in conflicts around the world.

Advertisement

“Art is in the eye of the beholder, right? This is just a way of expressing ourselves,” Guetzloe said. “It's freedom of expression in a much louder way.”

When I pointed out that most art isn’t also a deadly weapon, Guetzloe replied, “It could be used for harm. But I feel like most people that are going to do that are going to go out and steal one. The amount of effort that you put into these, you're not going to do that just to go and do someone harm.”

Even after 22 hours of work, my gun didn’t work properly. At the competition, it jammed repeatedly, and I was unable to finish round one of the contest. Pincus suggested swapping on a Glock-brand slide and barrel, which he had on hand. The factory part plus a little bit of gun oil made all the difference.

I loaded a clip into the gun and racked the new slide, which smoothly locked into place. Taking aim at a target, I squeezed off a few rounds in a row. The spent shell casings popped out of the chamber and were instantly replaced by fresh bullets; my semi-automatic gun finally worked semi-automatically. To test what it could do, I unloaded the rest of the clip rapid-fire—boom-boom-boom-boom. There were no jams. It worked (almost) like a real Glock.

The spent shell casings popped out of the chamber and were instantly replaced by fresh bullets; my semi-automatic gun finally worked semi-automatically. To test what it could do, I unloaded the rest of the clip rapid-fire—boom-boom-boom-boom. There were no jams. It worked (almost) like a real Glock.

Law Enforcement Isn’t Thrilled With 3D Guns

Making a fully-functioning semi-auto handgun from plastic and a few metal parts, it turns out, is totally legal (at least in Florida), but there are other applications for 3D-printing beyond guns that are troubling for law enforcement. Federal gun laws are enforced by the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), and it’s the explosives aspect of the agency’s mission that is increasingly overlapping with 3D-printing.

John “J.D.” Underwood, the special agent in charge of the ATF’s National Center for Explosives Training and Research, told me that 3D-printed land mines are already a possibility. He showed me a 3D-printed “bomblet,” which could be attached to a drone and dropped from the sky. Such devices, he said, have already been used against U.S. troops in the Middle East.

Such devices, he said, have already been used against U.S. troops in the Middle East.

Advertisement

“Nobody or anything's stopping somebody from making this in the United States today,” Underwood said, holding up the miniature plastic bomb in his hand.

When I asked Guetzloe, the AWCY moderator, about the group’s 37mm launcher, he told me the sole purpose is for firing signal flares. But the under-barrel tube version looks very similar to the military equivalent, a 40mm grenade launcher adapted by the Army for 3D-printing in order to save taxpayers money by lowering production costs.

Underwood was impressed with the designs on display at the Florida shooting match, and he stressed that the ATF has no problem with law-abiding gunmakers using 3D-printers.

“As long as they're used for their intended purposes by people that legally can have firearms, I don't have an issue with that,” he said. “It's when people use those firearms for criminal purposes, that's when it becomes a problem. ”

”

Last December, ATF agents raided the offices of Nevada-based Polymer80, the largest ghost gun company and seller of a popular “Buy Build Shoot” kit. No charges were filed and no employees were arrested, and the company continues to advertise pistol kits, though all the options are currently out of stock.

Advertisement

Polymer80 also faces civil lawsuits, most recently from two Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies who sued the company for selling an “untraceable home-assembled” Glock kit that was later used by a gunman who seriously wounded them in a Compton shooting. The deputies allege the company “purposefully sold their products without markings to make it difficult for law enforcement to trace the firearm.”

“Untraceable ghost guns are now the emerging guns of choice across the nation.”

The gun control group Everytown Law is also suing Polymer80 and other ghost gun makers. One case, which also involves the city of Los Angeles, accuses the company of creating a public nuisance and violating California’s business code. According to the LAPD’s chief, 700 ghost guns seized in the city last year were made from Polymer80 parts, including more than 300 in South LA, where homicides have been on the rise.

According to the LAPD’s chief, 700 ghost guns seized in the city last year were made from Polymer80 parts, including more than 300 in South LA, where homicides have been on the rise.

“Untraceable ghost guns are now the emerging guns of choice across the nation,” LA City Attorney Mike Feuer said when announcing the lawsuit in February. “Nobody who could buy a serialized gun and pass a background check would ever need a ghost gun. Yet we allege Polymer80 has made it easy for anyone, including felons, to buy and build weapons that pose a major public safety threat.”

Advertisement

A Polymer80 spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.

The company’s website states there is “a strict policy against selling 80% lower receivers to persons known to us to be convicted felons or otherwise prohibited persons.”

It also says building a gun from a kit provides customers with “a fun learning experience and a greater sense of pride in their completed firearm.”

Melting the Ghost Gun

I’d be lying if I didn’t say I was slightly proud (and more than a little terrified) of my ghost Glock. I somehow ended up taking third place in the 3D-printed pistol category. Just like me, some of my competitors seemed to spend more time behind a computer screen than at the firing range. I was told some shooting clubs prohibit ghost guns or 3D-printed guns, making it difficult to find a place for target practice. And reliability was clearly an issue, as many people—even the most advanced builders—suffered malfunctions and jams. The guns may look badass, but they don’t yet quite stack up evenly to the real thing.

I somehow ended up taking third place in the 3D-printed pistol category. Just like me, some of my competitors seemed to spend more time behind a computer screen than at the firing range. I was told some shooting clubs prohibit ghost guns or 3D-printed guns, making it difficult to find a place for target practice. And reliability was clearly an issue, as many people—even the most advanced builders—suffered malfunctions and jams. The guns may look badass, but they don’t yet quite stack up evenly to the real thing.

But as 3D-printing technology improves, making a 100% DIY ghost gun will become easier and easier. Even if there's a ban on “80 percent” kits, anyone with access to a printer, a few hundred dollars, and some free time will still be able to crank out a semi-auto pistol, one with no paper trail to identify the owner. In the eyes of Pincus and others at the shooting match, this is actually a good thing.

“I know this is counterintuitive for a lot of people, but the more people who have guns, the more normal gun ownership is, the more responsible the community will be and also the more educated the community will be in judging responsibility,” Pincus said. “I don't think everybody should have a gun. I think everybody who wants to be a responsible gun owner should have that option.”

“I don't think everybody should have a gun. I think everybody who wants to be a responsible gun owner should have that option.”

Since I live in California, one of the states that regulates ghost guns like other firearms, I would need to register my gun with local authorities. Such laws, however, have done little to contain ghost guns. Last week, the city of San Francisco sued three companies that sell do-it-yourself ghost gun kits, alleging they target buyers who are banned from owning guns and want to evade background checks.

“Ghost guns are a massive problem in San Francisco—they are becoming increasingly involved in murders, attempted murders, and assaults with firearms,” said San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin. “We know that the rise in gun violence is connected to the proliferation of, and easy access to, guns that are untraceable, guns that are easier to obtain by people who would be otherwise prohibited by law from getting them.”

I have no interest in owning a handgun—let alone one with “Ghost Gun” on the handle—so I decided to melt down the frame and return the gun to its original form: molten plastic.

Miguel Fernández-Flores contributed reporting.

3D printed weapons: myth or reality?

Photo: Scott Olson / Getty Images

Is it possible to create a pistol, submarine or grenade launcher using 3D printing and without legal consequences? logos on a 3D printer is gradually entering the industrial circulation. Many are wondering what the potential of this technology is. In September 2020, an underground workshop was found in Spain with two 3D printers, an exact copy of an assault rifle, and parts of other weapons. The trial in this case was classified as “secret” for several months, and the incident became known in early April 2021. Do 3D printers really allow you to create weapons that can be used in practice, or are they just plastic models?

A real weapon or a plastic toy

Alexander Golovin, a 3D printing engineer, said that the materials used in printers are not engineering materials. They are unlikely to hold the structure in the case of the production of weapons or other heavy items. The maximum that 3D printers are capable of so far is printing key rings, gifts and logos. Of course, you can also print a gun, but functionally it will not differ in any way from a children's plastic toy and it will not work to shoot from it.

The maximum that 3D printers are capable of so far is printing key rings, gifts and logos. Of course, you can also print a gun, but functionally it will not differ in any way from a children's plastic toy and it will not work to shoot from it.

The thing is that the material for a 3D printer is fragile and brittle. To create weapons, you need metal parts that could support the main warhead: the receiver, the barrel itself and the bolt. But you should not do this: for a fake design, you can get a real term.

Is it profitable to print weapons

Printed weapons are unlikely to pay off, and their production will take a long time. 3D printing of weapons on a metal printer will cost about ₽100 thousand. Meanwhile, a rifle in a store can be bought for ₽15 thousand. Of course, you will need to spend money on training and a safe, but it will still come out cheaper.

Even on the black market, the cost of such weapons is much less than the cost of entering the metal printing industry. What's more, it's illegal, so the chance of a 3D weapon maker getting caught increases exponentially.

What's more, it's illegal, so the chance of a 3D weapon maker getting caught increases exponentially.

News about the successful 3D printing of weapons: fact and fiction?

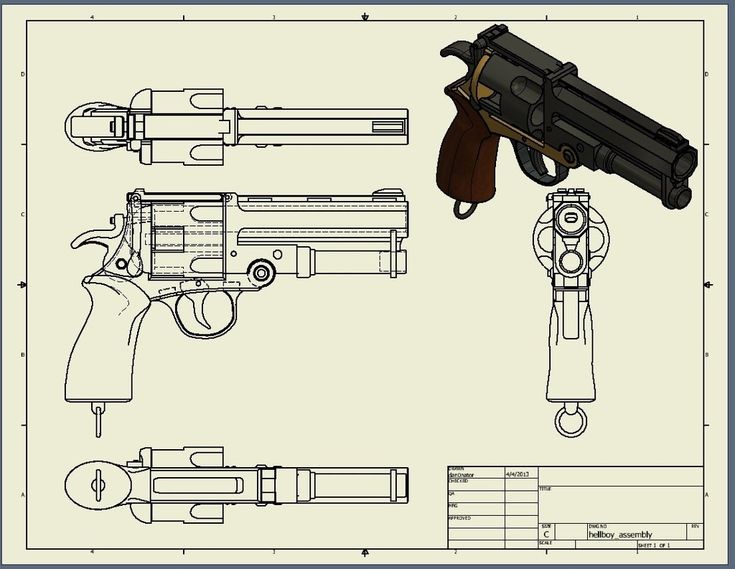

Back in 2013, Solid Concepts printed the Colt 1911 metal pistol. However, this news raises many questions. The classic "colt" has a rifled barrel - it is impossible to print one. Plus, the model requires grinding and processing.

The news that the US Army has built a 3D grenade launcher is a little embellished. It is quite possible to print a model of a grenade launcher, because this weapon is a pipe - it does not matter what it is made of. But it is unlikely that a 3D printer will be able to print explosives or projectiles. Even if this succeeds, when used, the plastic case will scatter in different directions.

Another 3D printing experiment belongs to the US Navy. They printed a submarine. Alexander explained that, most likely, only some part of the submarine was created - it is impossible to restore it completely without aluminum. The printed boat has a number of limitations related to the strength of the material and the loads it can take. Moreover, it is not known how well such a submarine will be able to dive into the water.

The printed boat has a number of limitations related to the strength of the material and the loads it can take. Moreover, it is not known how well such a submarine will be able to dive into the water.

The editors of RBC Trends reminds that the development, production and storage of weapons and their main parts are subject to licensing in accordance with the Russian legislation on licensing certain types of activities. Illegal manufacture, alteration or repair of firearms and illegal manufacture of ammunition are criminal acts .

3D printing weapons, 3d printer for printing weapons

Turch December 13th, 2014

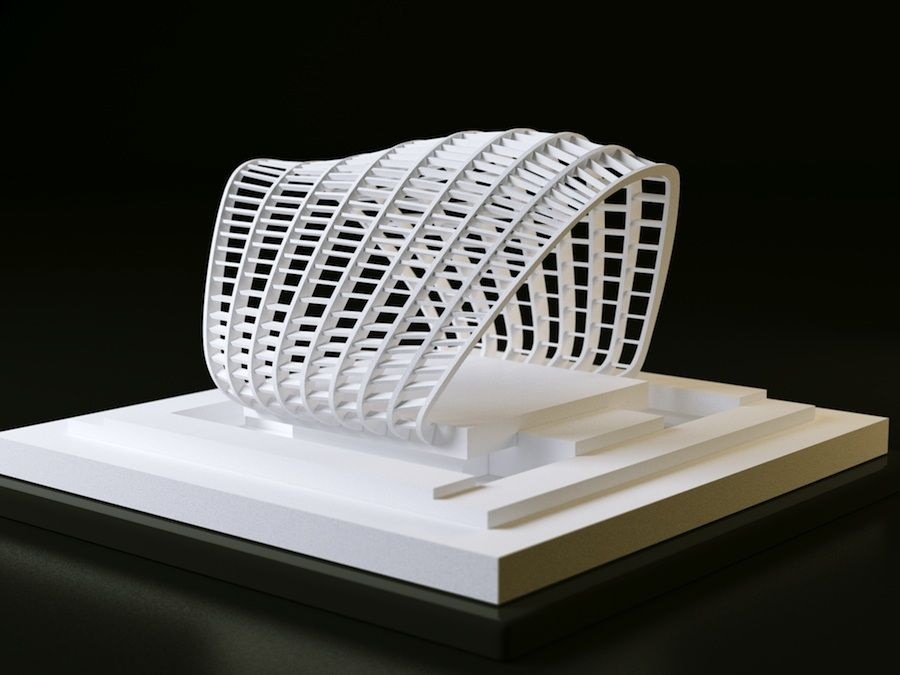

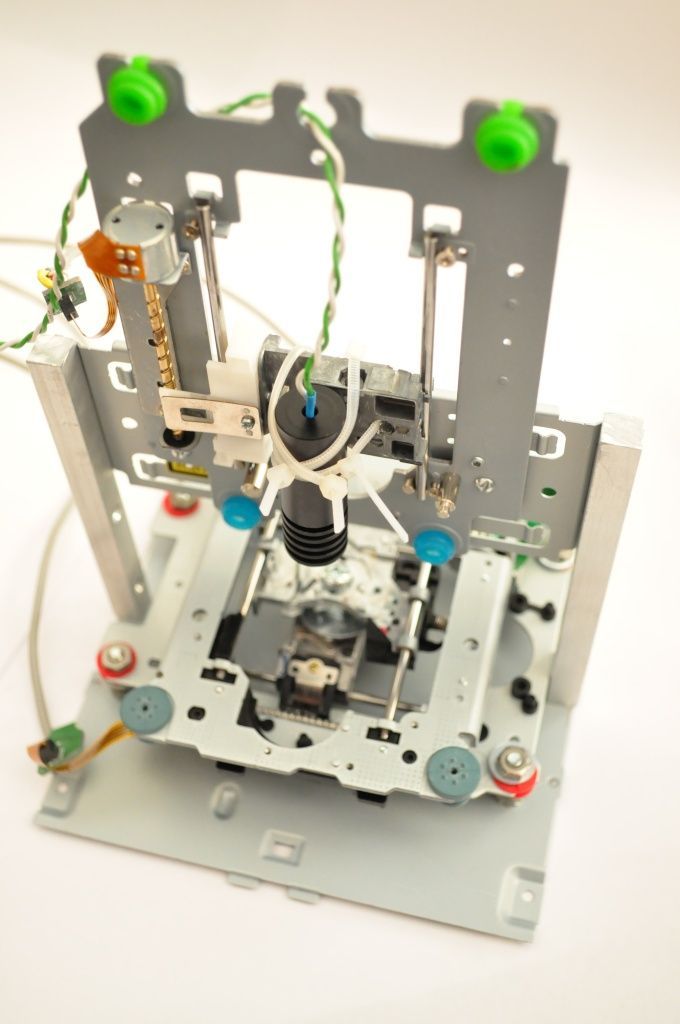

3D printing and 3D prototyping are synonyms for the production of physical objects according to a three-dimensional layout made in any graphic editor. This allows you to create structures of any complexity and work out internal details that are impossible to perform on modern equipment.

Types of 3D prototyping technologies:

- Extrusion is a method in which the material is first melted and then extruded in the desired proportions, determined by a given program.

- Granulation is a method in which material particles are glued together or sintered under the influence of high temperature.

- Laminating - applying thin layers of material on top of each other and then cutting out (as on a lathe).

- Photopolymerization - the process of polymer curing when exposed to a laser beam.

Regardless of the application of any of the existing technologies, the basic principle remains the same. Application of material ball by ball in three planes (X, Y, Z axis). 3D printing can be used in any field, as it allows you to create an object from scratch. It is enough to load its virtual layout.

3D printing materials weapons

Since 3D printing technology has a very wide scope, the materials are also quite diverse:

- Polylactide

- Petroleum products (plastic, nylon).

- Metal powder.

- Mixture of plastic and wood (wood fibre).

- Polycaprolaton.

- Polypropylene.

- Acrylic.

- Gypsum and others.

Polylactide

Plastic

Nylon

Metal powder (Product)

Wooden fiber 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 in fact, even food can be used in 3D printing. For example, chocolate. From it you can create edible figurines or a mini-sculpture of a person.

Equipment for 3D printing of weapons

A machine that converts a virtual model, by the method of ball-and-stick application of material, into a real object is called a 3D printer. It can be used at home (desktop) and commercially (industrial). The cost varies from 1,000 to 1,000,000 US dollars. Also, for each technology, a separate model of the device is provided.

Weapons on a 3D printer

The idea to print military weapons on a 3D printer first appeared in the United States of America.

In May of this year, a video appeared on the Internet in which a man shoots from a printed model of a Liberator pistol. It was 25-year-old Cody Wilson, head of Defense Distributed, which promotes the idea of universal availability of 3D weapons.

Using a 3D printer, they printed firearms and uploaded files of their work to the worldwide web. Defense Distributed employees have already made magazines that hold more cartridges for the AR-15s rifle and the legendary Kalashnikov assault rifle (AK-47 modification). Also on their account is the manufacture of the lower part of the receiver, in which the bolt of a self-loading rifle AR - 15 is placed. You can attach the barrel and magazine to it, having received a finished weapon without any problems. No authorization is required to purchase parts in the USA. Now work is underway on a 3D printout of the entire rifle. In doing so, Cody and his team dealt a major blow to the American gun control debate. The discussion began in December, after twenty children and six adults were killed by assassins at a junior high school in Connecticut. The vast majority of Americans rallied to support government reform. This is a thorough check that will make it difficult for criminals to obtain weapons. However, this did not prevent Mr. Wilson from obtaining a federal license to manufacture and sell firearms.

In doing so, Cody and his team dealt a major blow to the American gun control debate. The discussion began in December, after twenty children and six adults were killed by assassins at a junior high school in Connecticut. The vast majority of Americans rallied to support government reform. This is a thorough check that will make it difficult for criminals to obtain weapons. However, this did not prevent Mr. Wilson from obtaining a federal license to manufacture and sell firearms.

More serious developments in the field of printing firearms on a 3D printer are being carried out in Austin, Texas. The project is led by Eric Macler, coordinator at Solid Concepts, a 3D printing company.

Erik Machler

Ten industrial 3D printers are installed at the Austin plant. Solid Concepts received a federal license to manufacture weapons, and now, using direct metal laser sintering technology, produces the Browning 19 pistol.eleven". Making a pistol takes up to 35 hours. Depending on which printer and materials are used. More than 1,000 shots have already been fired from the first printed pistol, Solid Concepts, while the company has created a second version of the Browning 1911 model.

Depending on which printer and materials are used. More than 1,000 shots have already been fired from the first printed pistol, Solid Concepts, while the company has created a second version of the Browning 1911 model.

Solid Concepts is not going to mass-produce the gun because they can't sell it in a way that makes a profit. While many 3D printers cost around $1,000, Solid Concepts says hobbyists can't make the stainless steel gun they make. Since their machines cost between $600,000 and $1 million, industrial conditions are needed here. The devices consume more electricity than can be obtained in residential areas. In addition, the printers use inert gases that are not commercially available. So this is a technology for commercial production.

The first cases of arrests for making weapons on a 3D printer have already appeared. So, a Japanese citizen Yoshimo Imuro was detained by local law enforcement agencies for carrying military weapons, which he printed on a 3D printer.