3D printing ear

Woman Gets New Ear Made of Her Own 3D-Printed Cells

June 2, 2022 – Doctors in the U.S. have successfully transplanted a 3D-printed ear implant that uses the patient’s cells.

The first “bioprinted living tissue implant” went to a 20-year-old woman, who was born with a small and misshapen ear. The implant was printed in a shape that matched her other ear and “will continue to regenerate cartilage tissue,” which will help it to look and feel like a natural ear, according to The New York Times.

3DBio Therapeutics, a regenerative medicine company based in New York City, is doing an early-stage clinical trial with patients who have microtia, a rare congenital disorder where one or both outer ears are absent or underdeveloped. The disorder affects about 1,500 babies born in the U.S. each year and typically has limited reconstruction options.

3DBio and the Microtia-Congenital Ear Deformity Institute, in Texas, did the human ear reconstruction using the AuriNovo implant, which received FDA designations for orphan drug and rare pediatric disease in 2019.

“As a physician who has treated thousands of children with microtia from across the country and around the world, I am inspired by what this technology may mean for microtia patients and their families,” Arturo Bonilla, MD, a pediatric ear reconstructive surgeon specializing in microtia who performed the surgery, said in a statement.

The clinical trial is looking at how safe and effective the AuriNovo implant will be, with the goal of replacing current ear reconstruction surgeries that require doctors to use rib cartilage or certain implants.

“The AuriNovo implant requires a less invasive surgical procedure than the use of rib cartilage for reconstruction,” Bonilla said. “We also expect it to result in a more flexible ear than reconstruction with a PPE [porous polyethylene] implant.”

3DBio announced the results of the patient’s surgery in a news release on Thursday, which didn’t include technical details of the procedure because of privacy reasons. The company said the FDA has reviewed the clinical trial design and set strict manufacturing standards. The data is expected to be published in a medical journal when the study is complete.

The data is expected to be published in a medical journal when the study is complete.

The manufacturing process begins by taking a small sample of the patient’s ear to create billions of cartilage cells. The living cells are then mixed with the company’s collagen-based “bio ink,” which is safe for the body. The 3D bio-printer uses that ink to create an object based on a digital model that copies the patient’s healthy ear.

The ear implant procedure, which was done in March, marks one of several recent breakthroughs in organ and tissue transplants, the Times reported. Numerous companies across the world are developing implants that use 3D-printed technology to help patients with deformities and other health issues.

With more research, the technology could be used to make other body parts, including spinal disks, noses, knee cartilage, rotator cuffs, and reconstructive tissue for lumpectomy procedures, 3DBio said. In the more distant future, 3D printing could potentially create vital organs, such as livers, kidneys, and pancreases.

The clinical trial, which is also enrolling patients at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, has included 11 volunteers ages 6 to 25 so far. The patients will be followed for 5 years to evaluate long-term safety and satisfaction.

A surgically implanted, 3D-printed ear marks a medical advance

Science News

3DBio Therapeutics, the company that manufactured the ear, said in a news release Thursday said the procedure had been a success.

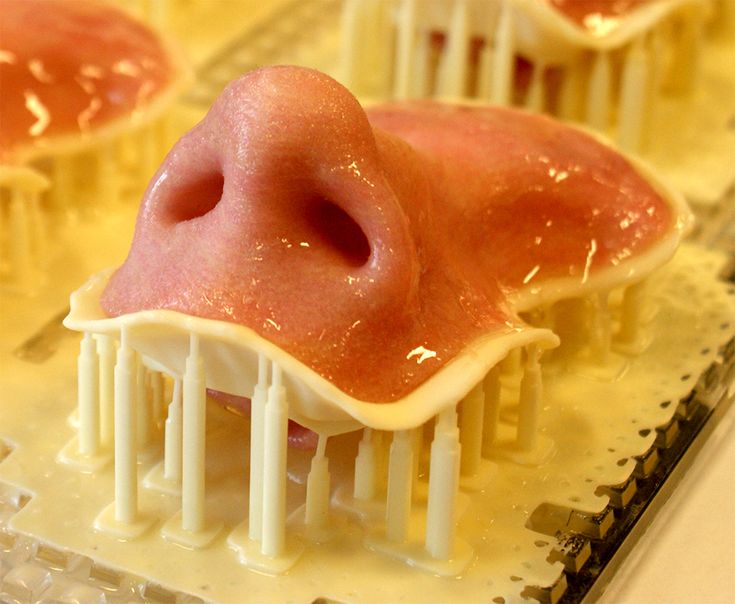

An ear implant sits within cell culture media atop the metal base of a printer.3DBio TherapeuticsBy Evan Bush

In a first for medicine, a surgeon has successfully implanted an outer ear developed and 3D-printed in a laboratory.

A 20-year-old woman who was born with the congenital disorder microtia and had one misshapen ear received the new appendage in March, 3DBio Therapeutics, the company that manufactured the ear, said in a news release Thursday. The ear was constructed from her own cells as a mirror replica of her other ear.

The ear was constructed from her own cells as a mirror replica of her other ear.

Outside experts said it is the first time that 3D-printed tissue had been implanted into a human body.

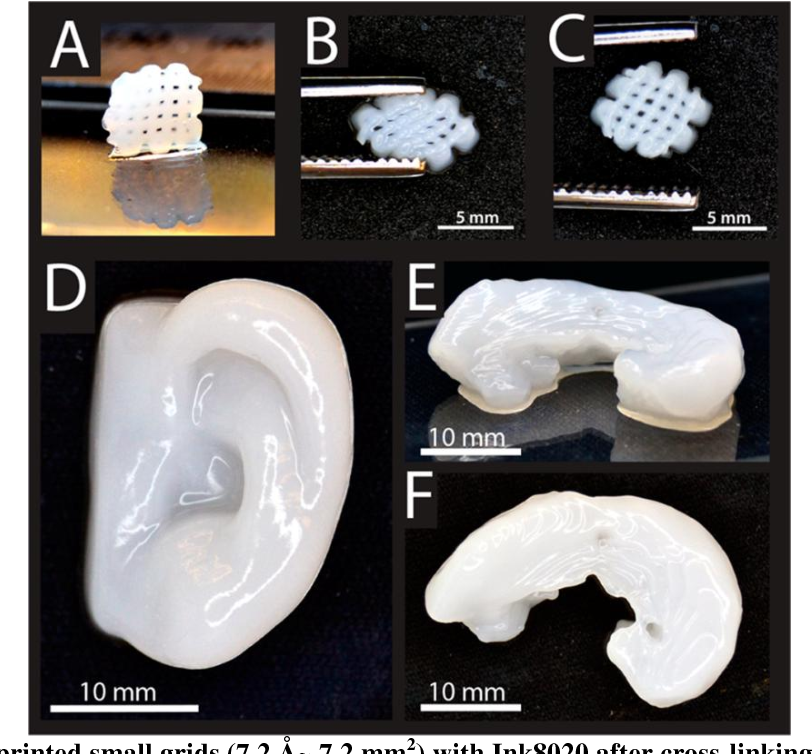

A collagen ear implant sample on display.3DBio Therapeutics“It’s a big milestone,” said Dr. Anthony Atala, the director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. “Ears have been implanted by hand. It’s now using a printer, which helps automate the process, which is important for the field.”

The milestone could open doors for investment and new excitement around 3D tissue printing, potentially paving the way for new therapies in regenerative medicine.

“I’m hoping these kinds of success will build enthusiasm and understanding this is moving from the realm of science fiction into reality,” said Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and chief technology officer for Fluidform, a 3D bioprinting startup.

Microtia patients are born without outer ears or with appendages that are smaller and different in shape.

“A lot of these children experience psychological and social impacts from growing up without an outer ear,” said Dan Cohen, a co-founder and the CEO of 3DBio Therapeutics.

For microtia patients today, surgeons often carve into a child’s rib cage to shave off cartilage and then construct an ear.

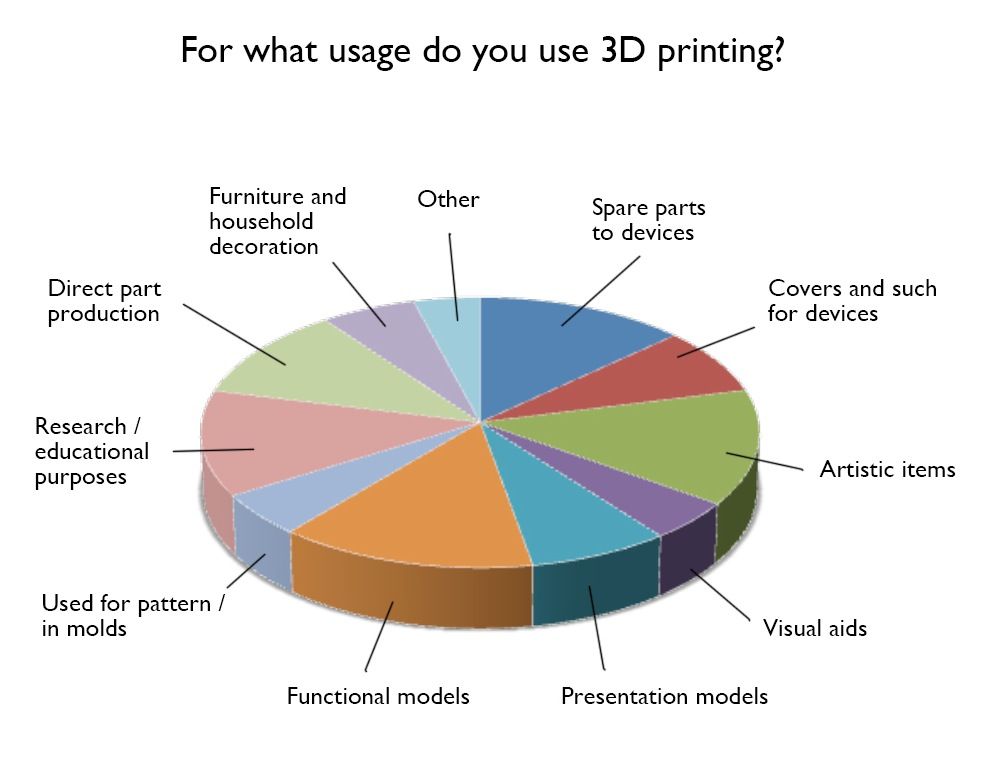

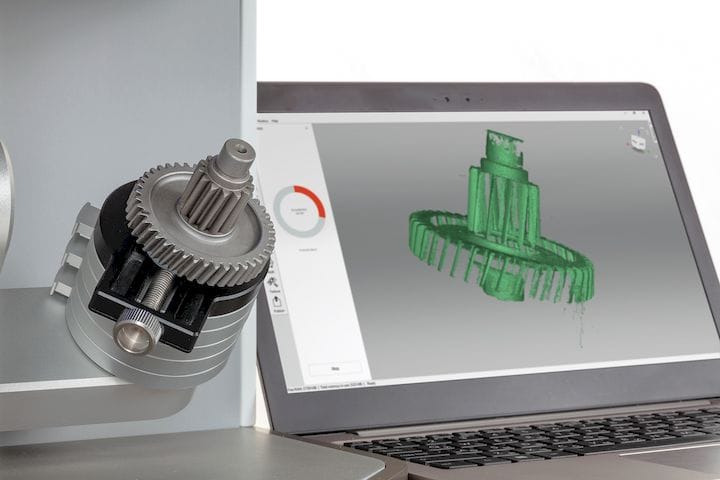

3D printing, in which a machine creates a three-dimensional object from raw materials, could reduce risks. The process is also used to create houses to recycled tools on the International Space Station.

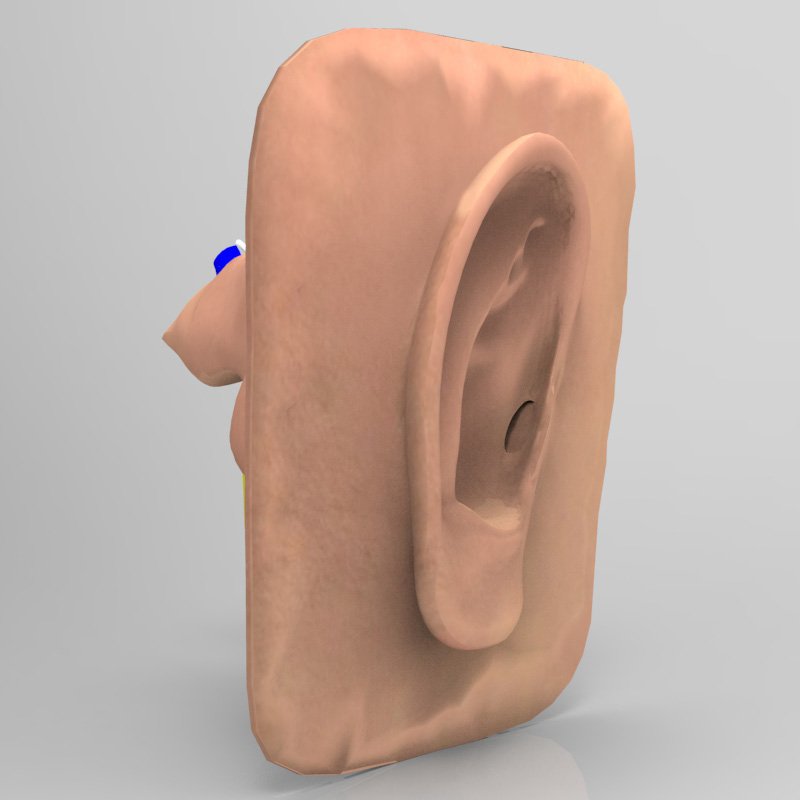

To print an ear, 3DBio Therapeutics scientists first built a three-dimensional computer model, based on a scan of the woman’s other ear. Then, they cultured living cells and put them into a “bioink” made of collagen. A printer then deposited the bioink layer after layer to create the right shape — a mirror image of the woman’s ear. A final biodegradable shell shields the implant while it generates cartilage.

“In this case, you don’t have to go into the rib cage and expose the lungs to infection and have other surgical risks,” said Adetola Adesida, a professor in the department of surgery at the University of Alberta, who was not involved in the implant.

Implanting a printed ear is much the same procedure as typical, Cohen said. Dr. Arturo Bonilla, a San Antonio-based pediatric ear reconstructive surgeon specializing in microtia, performed the March surgery.

In a news release, Bonilla said he hoped 3D printing would become the new standard of care for microtia patients.

The implant was part of an ongoing clinical trial involving 11 patients.

Patient's ear before surgery, left, and patient's ear 30 days post surgery. Courtesy Dr. Arturo Bonilla / Congenital Ear InstituteThe company said it will share its clinical safety and efficacy data upon the trial’s completion. Without clinical trial data, the outside experts could not evaluate the methods used to construct the ear in detail. The outside experts who spoke with NBC News said the research appeared to be credible.

Feinberg said getting a green light from Food and Drug Administration regulators to pursue the research signals that the company has a reliable process.

The development of the ear could pave the way for more ambitious projects, Feinberg said.

“The ear is a relatively simple organ. It has some function. It does help funnel sound into the air,” Feinberg said. “We’re thinking of it mostly as a cosmetic outcome. The next step is to build more functional tissues or organs. It’s a much higher bar.”

3D printing technology could also help scientists scale regenerative medicine solutions that have been produced in laboratories but are not available broadly.

“3D printing is a really great tool to be able to automate the process,” Atala said. “It brings automation, reproducibility. It brings reliability. It brings decreased cost.”

Evan Bush

Evan Bush is a science reporter for NBC News. He can be reached at [email protected].

For the first time, a 3D-printed ear was transplanted to a patient / Sudo Null IT News For a 20-year-old patient with a deformity of the right ear, a special ear implant was made from her own cells.

Patient before and 30 days after surgery / Microtia-Congenital Ear Institute

Patient before and 30 days after surgery / Microtia-Congenital Ear Institute According to independent medical experts who evaluated the technology's first clinical trial, this transplant was a breakthrough in tissue engineering.

A patient from Mexico was born with microtia, a rare birth defect that deforms the pinna or outer part of the ear.

The 3D printing manufacturing process typically involves a computer-controlled printer applying material in thin layers to create the exact shape of an object. The new ear implant from 3DBio Therapeutics combines several patented technologies, starting with a method to turn a small sample of a patient's cells into billions of cells. The company's 3D printer uses collagen-based "bio-ink", which is safe for the body and ensures the sterility of all materials.

A surgeon removed 0.5 g of cartilage from a woman's deformed ear. Chondrocytes, the cells responsible for cartilage formation, were then isolated from a tissue sample and grown in a proprietary suspension of nutrients. Live cells were mixed with bioink. Collagen was injected through a syringe into a specialized 3D bioprinter, which extruded the material from the nozzle in an even, thin stream, moving in a circle, creating a small oblong shape that was a mirror image of the patient's healthy ear. The entire printing process took less than 10 minutes.

Live cells were mixed with bioink. Collagen was injected through a syringe into a specialized 3D bioprinter, which extruded the material from the nozzle in an even, thin stream, moving in a circle, creating a small oblong shape that was a mirror image of the patient's healthy ear. The entire printing process took less than 10 minutes.

The printed ear shape was then placed in a protective biodegradable shell and placed in the refrigerator overnight. The next day, it was implanted under the patient's skin just above the jawbone. As the skin tightened around the implant, the shape of the ear appeared.

3DBio Therapeutics notes that their implant is more cosmetic. According to them, after transplantation, the ear will independently regenerate cartilage tissue, acquiring the appearance of a natural organ.

The company's specialists estimate the probability of implant rejection as low, since the cells for printing the organ were taken from the patient's own tissues.

Transplant performed by Dr. Arturo Bonilla, Pediatric Reconstructive Surgeon in San Antonio. “If everything goes according to plan, this technology will be revolutionary,” he said.

In total, 11 people are currently participating in clinical trials for the transplantation of such implants. With more research, the technology could be used to make other implants, including intervertebral discs, noses, knee menisci, and reconstructive tissues for laparectomy, the company's executives said. Perhaps in the future, much more complex vital organs, such as the liver or kidneys, could be produced using 3D printing.

Meanwhile, United Therapeutics Corp. experimenting with 3D printing to produce lungs for transplantation. And scientists at the Israel Institute of Technology reported in September that they had 3D printed a network of blood vessels needed to supply blood to implanted tissues.

The first operation to transplant a 3D-printed ear will be performed on a two-year-old girl

Maya's diagnosis is microtia, that is, insufficient development of the auricle. Many people with deformed ears can still hear, but Maya is missing her left ear and auditory canal. Now the girl wears a special bandage on her head, which transmits sound signals to her brain, passing them through the bones of the skull. Although Maya may not yet realize that she does not have an ear, she will soon realize that she is different from other children.

Many people with deformed ears can still hear, but Maya is missing her left ear and auditory canal. Now the girl wears a special bandage on her head, which transmits sound signals to her brain, passing them through the bones of the skull. Although Maya may not yet realize that she does not have an ear, she will soon realize that she is different from other children.

Promising research is part of the local government's Advance Queensland initiative, which has already raised funds for the development of cartilage implants. According to project leader Professor Mia Woodruff, A$125,000 has already been received from public and private sources. She says that these funds should be enough to develop anatomically correct ears from the patient's own cartilage cells. The team already has an outstanding team and the researchers expect to raise another A$50,000 by the end of the year through crowdfunding.

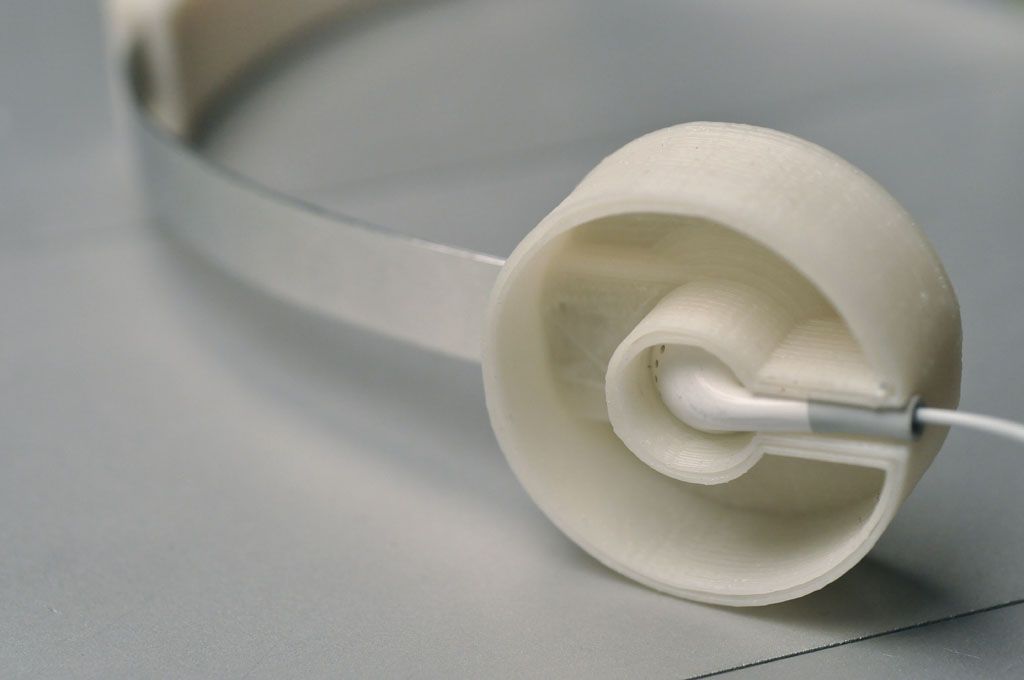

The project is divided into two main stages, the first of which is the simplest, short-term cosmetic solution. This is done by 3D printing an auricle made of medical silicone and fixing it. In the near future, this task can be completed in a matter of hours - this solution is ideal for patients with deformed or damaged ears.

This is done by 3D printing an auricle made of medical silicone and fixing it. In the near future, this task can be completed in a matter of hours - this solution is ideal for patients with deformed or damaged ears.

As for the long-term stage, it is much more ambitious and represents a complex bioengineering solution. The task of the researchers is to develop a method for 3D printing an ear from the patient's own cells. After a few weeks of cultivation, such an ear could be surgically transplanted into the patient. Hearing function would be restored through an individual bionic technique. If research is successful, this treatment could cost as little as $200 per child.

According to Professor Woodruff, both phases of the project involve radical innovation. “This will be the first 3D printed ear prosthesis in the world,” she says. “With the help of 3D scanning, we can transfer information to a 3D printer and immediately print an ear. I think it would be cheaper to 3D print a prosthetic ear than a pair of glasses.