3D printing copyright issues

How 3D Printing Challenges Trademark, Copyright, and Patents

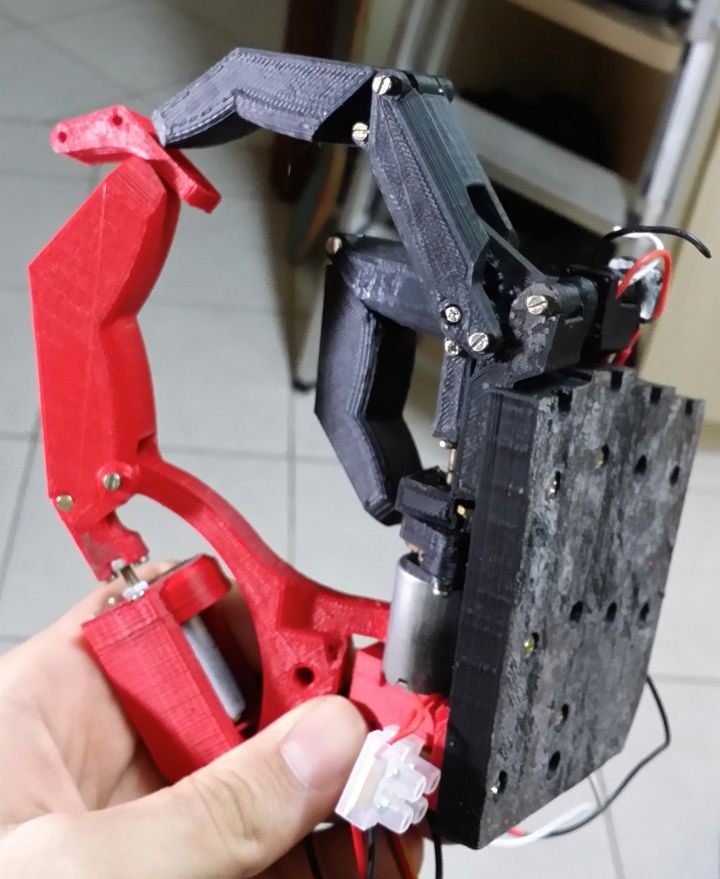

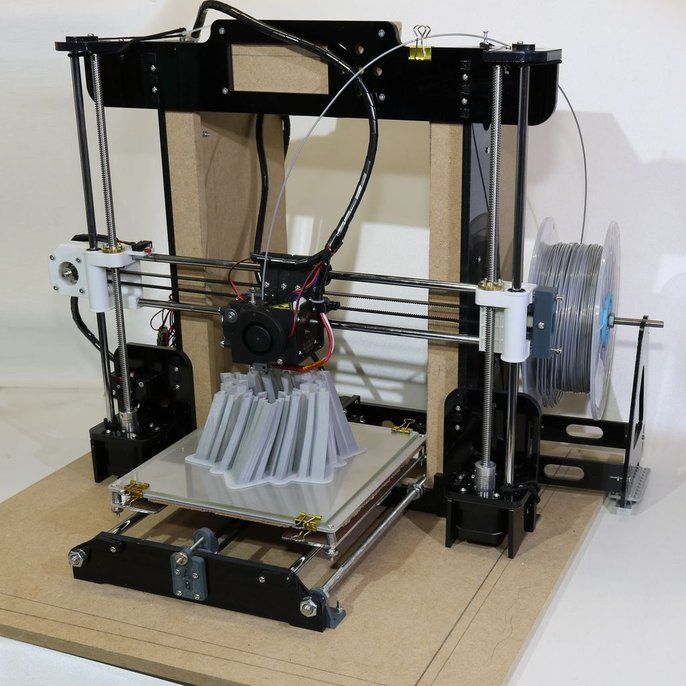

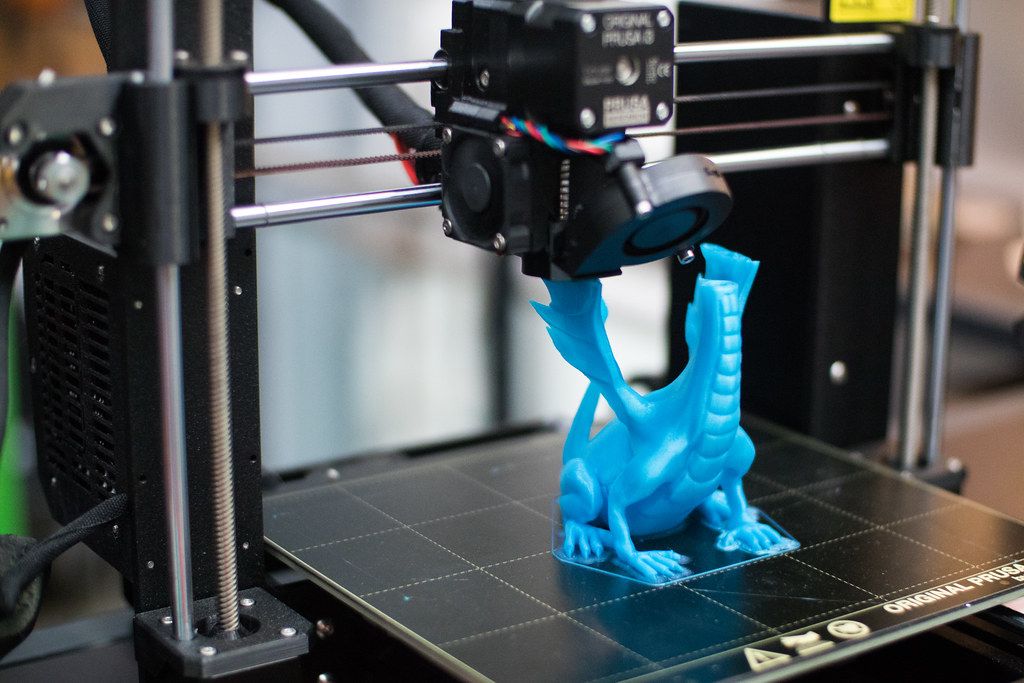

Skip to content3D (three-dimensional) printing technology began in the 1980s, however, the increase and advancement of technology has allowed consumers the ability to access low cost 3D high-performance printers. With great technology comes great challenges to existing laws that never could have anticipated the future impact of these rapidly changing industries. With the market for 3D printers growing by 20% every year, any person can now own a 3D printer, which has vast implications on trademark, copyright, and patent law.

Recently, while dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, a hospital in Italy experienced a shortage of special valves used in breathing machines needed by COVID-19 patients. Local engineers recreated the valve design digitally and printed it with a 3D printer, without the permission of the patent holder. The incident, which involved a U.S. company, not only highlights potential ethical concerns in enforcing such intellectual property (IP) rights during a medical emergency, but also the relative ease with which infringement of IP rights can occur through the use of 3D printers.

Trademark Law

A trademark is an identifying mark like a name, logo, or slogan, that allows consumers to connect a good or service to its source. In the United States, trademark rights are conferred by first use, not first to file a registration; however, registering a trademark federally provides significantly more legal protection and options to the rights holder.

Trademark infringement occurs when the mark is used without permission in connection with a sale and is likely to lead to confusion, deception, or mistake as to the source of the goods or service. Trademark infringement using 3D printers can lead to consumer confusion when infringing material is placed in the stream of commerce and, in turn, damage the reputation and business of the rights holder. It will not likely matter if the trademark appears differently and not identically when printed in 3D because the standard of determining if the unauthorized mark will lead to confusion is whether a consumer is likely to be confused as to the source of the mark.

Copyright Law

Copyright is a legal right held by the creator of an original work. This right arises immediately after an original, tangible work is created. There is no requirement to register a work with the U.S. Copyright Office; however, doing so provides added legal protection and tools to enforce the copyright.

Copyright infringement refers to the unauthorized reproduction, duplication, distribution, or creation of a derivative work of an original work. With advanced 3D printing technology, any person may scan a copyrighted work and reproduce that original work. If any object is scanned without the original owner’s permission, and printed on a 3D printer, it may constitute copyright infringement.

In an innovative response to the growing trend of 3D printing, Hasbro announced a partnership with the 3D printing marketplace, Shapeways in 2014, to allow My Little Pony fans to freely create fan art with 3D printers. This unique strategy allowed Hasbro to keep control over their copyright and find a compromise for fans.

Patent Law

A patent provides legal rights to the owner of an invention or mechanism that prevents any other person from manufacturing, using, selling or importing the product, substance, or process under patent protection. There are three different types of patents: utility patents, design patents, and plant patents.

As with trademark law and copyright law, if a person takes a product or process, and reproduces it with a 3D printer, that may constitute patent infringement. Patent infringement occurs when a party makes, uses, sells, or offers the invention without the permission of the patent holder. Patent holders should monitor the marketplace vigilantly for infringement of their 3D printed products.

Contact an Experienced Intellectual Property Attorney

If you are concerned about how the growing trend of 3D printing may affect your intellectual property rights, contact an experienced intellectual property attorney at The Myers Law Group at 888-676-7211 or online today.

Categories

- Business

- Business Formation

- Business Litigation

- Copyright

- Current Issues

- Intellectual Property

- Patents

- Real Estate

- Trade Secrets

- Trademarks

Archives

- May 2022 (6)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (4)

- February 2022 (4)

- July 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (2)

- September 2019 (3)

- August 2019 (2)

- June 2019 (3)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- January 2019 (3)

- May 2018 (2)

- April 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- November 2017 (3)

- September 2017 (2)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (2)

- May 2017 (2)

- March 2017 (3)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (1)

- October 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (3)

- June 2016 (1)

- September 2015 (3)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (5)

- May 2015 (7)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (6)

- February 2015 (7)

Recent Posts

- Three Songwriter’s Claim Sam Smith and Normani’s “Dancing with a Stranger” Copied Their Song of the Same Name

- Dua Lipa Sued Twice in One Week for Copyright Infringement Over Hit Song “Levitating”

- Why Is Litigation Bad for Business?

- What Is Litigation in a Business?

- Pay-Per-View Provider’s $100 Million Suit Against Alleged Illegal Streamers for Jake Paul vs.

Ben Askren Fight Ends in Failure

Ben Askren Fight Ends in Failure

3D printing and IP law

February 2017

By Elsa Malaty, Lawyer, Associate in the law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP, and Guilda Rostama, Doctor in Private Law, Paris, France

3D printing technology emerged in the 1980s largely for industrial application. However, the expiry of patent rights over m�any of these early technologies has prompted renewed interest in its potential to transform manufacturing supply chains. The availability of low-cost, high-performance 3D printers has put the technology within reach of consumers, fueling huge expectations about what it can achieve. But what are the implications of the expanding use of this rapidly evolving and potentially transformative technology for intellectual property (IP)?

Using a commercially available 3D printer, researchers at the National University of Singapore have found a way to print customizable tablets that combine multiple drugs in a single tablet so doses are perfectly adapted to each patient. (Photo: Courtesy of the National University of Singapore).3D printing in a nutshell

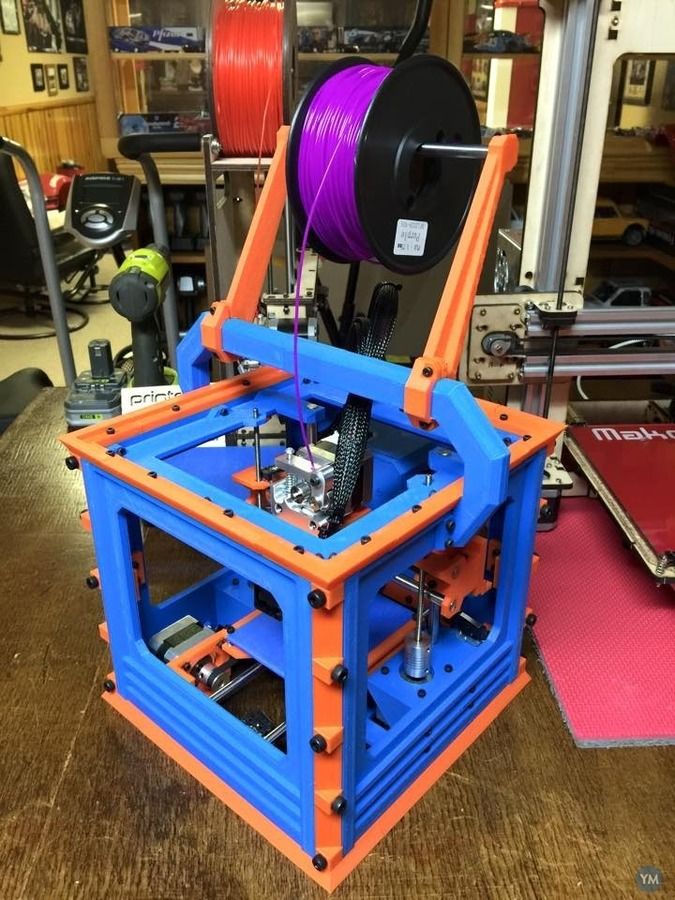

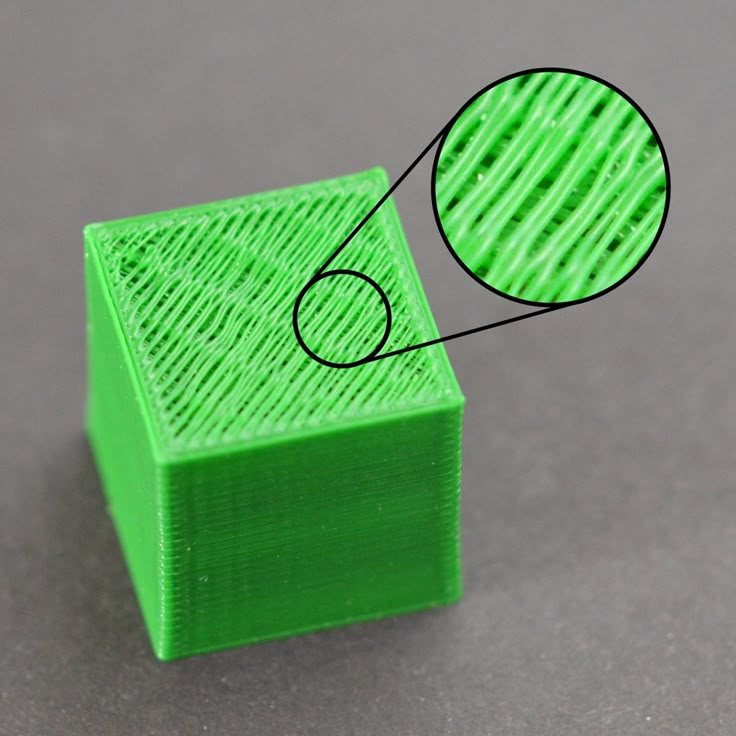

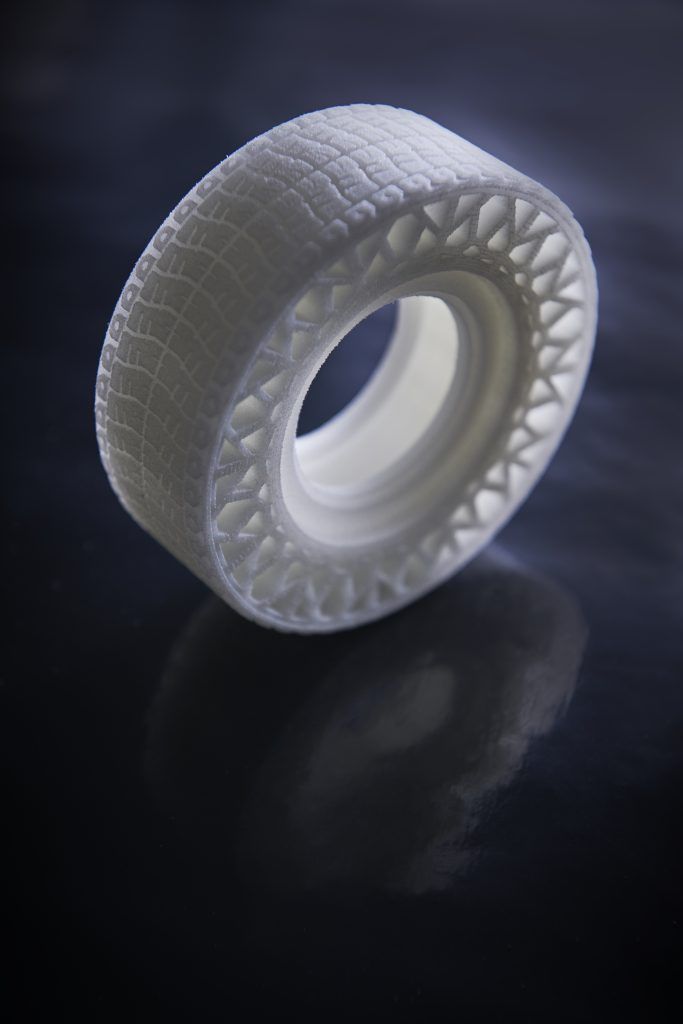

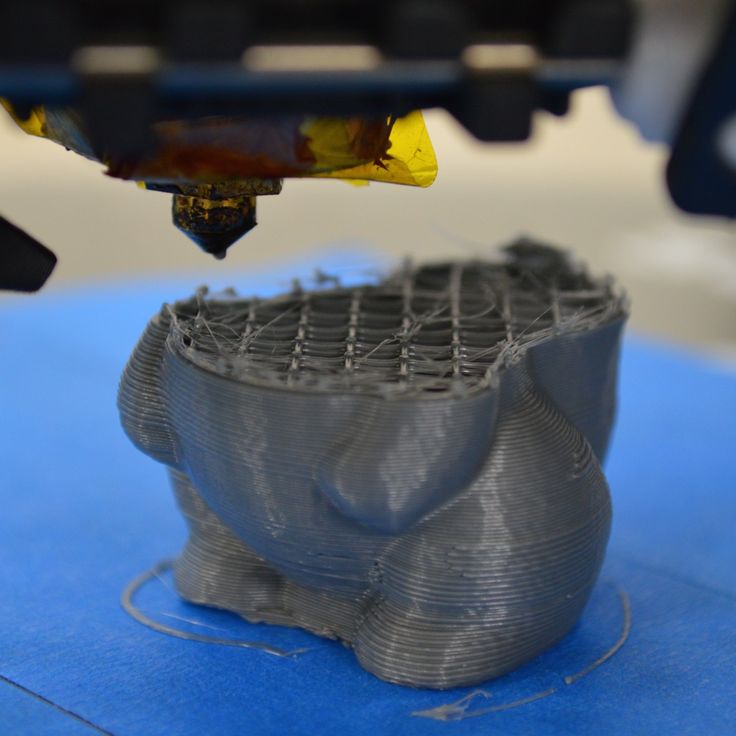

(Photo: Courtesy of the National University of Singapore).3D printing in a nutshellThe 3D printing process starts either with a digital file in which the object to be printed is digitally formatted using either 3D print software, or a 3D scanner. The file is then exported to a 3D printer using dedicated software, which transforms the digital model into a physical object through a process in which molten material is built up layer upon layer until the finished object emerges. This process is also referred to as additive manufacturing.

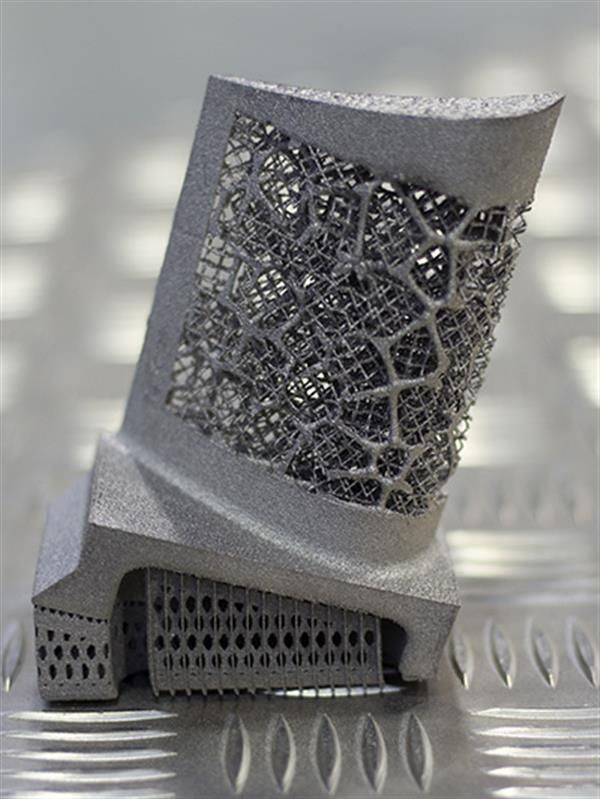

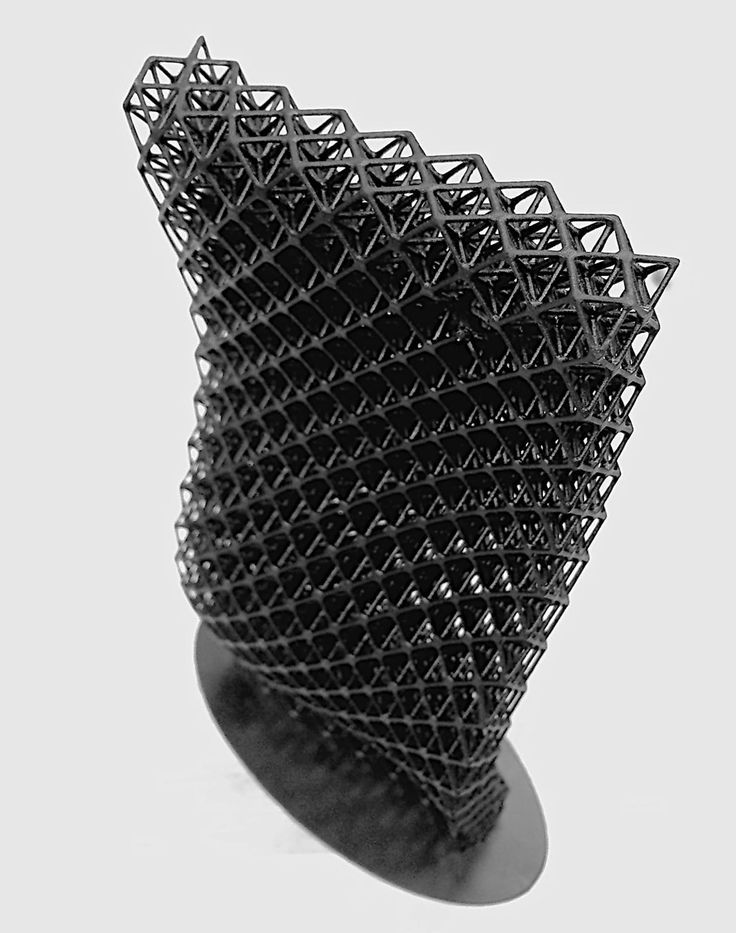

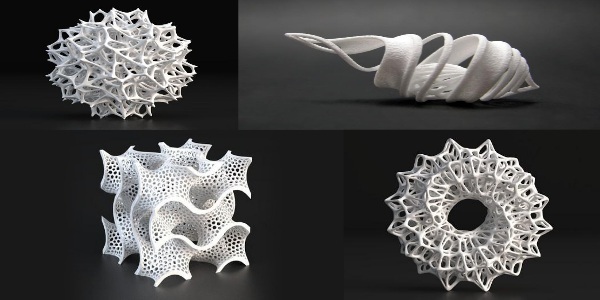

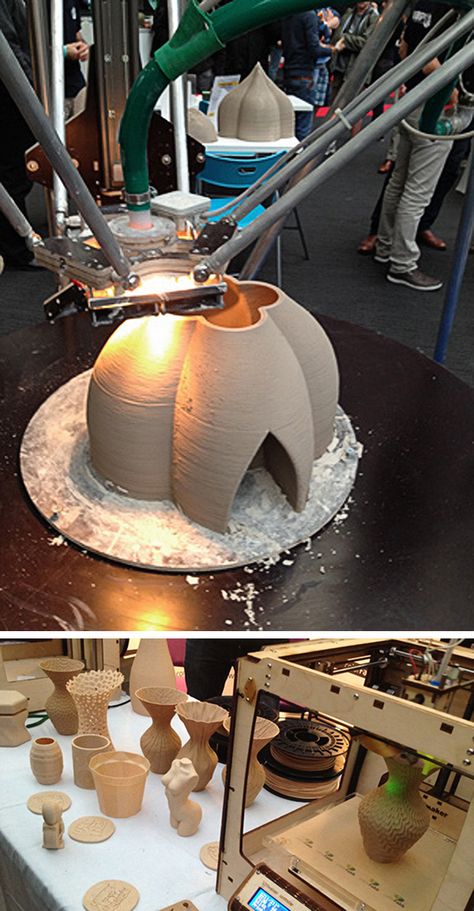

The 3D printers available today use a variety of materials ranging from plastics to ceramics, and from metals to hybrid materials. The technology is evolving at a breathtaking pace. For example, MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory recently developed a 3D printing technique to print both solid and liquid materials at the same time using a modified off-the-shelf printer, opening up a huge range of possible future applications.

3D printing technology is evolving at a breathtaking pace, with applications in areas ranging from food and fashion to regenerative medicine and prosthetics.

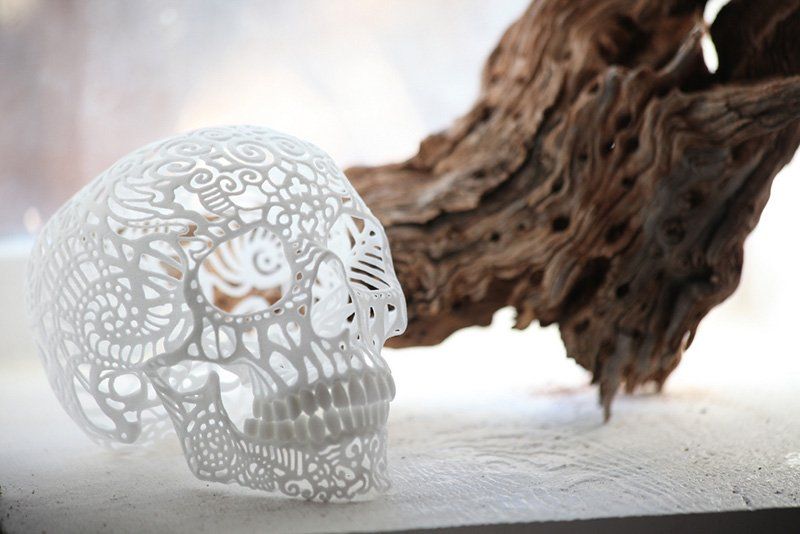

The expanding range of materials used for 3D printing means that the technology’s application is having an impact on a whole range of industries, fostering new opportunities for innovation and business development.

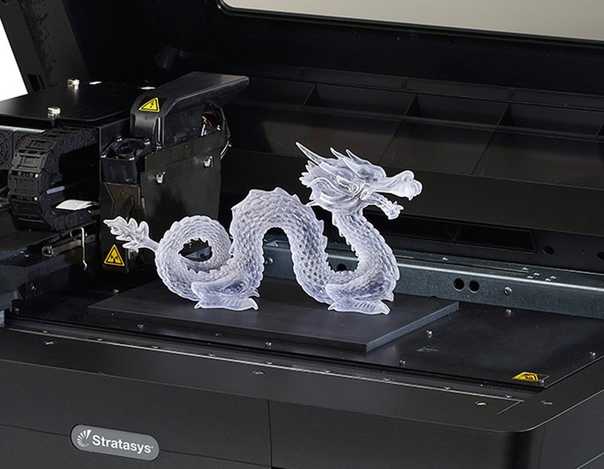

Even food is being 3D printed! It makes it possible to automate certain time-consuming aspects of food preparation and assembly, makes it easier to create freshly made snacks, has huge scope for food customization and can convert alternative ingredients like proteins from algae, beet leaves and insects into tasty meals! (Photo: Courtesy of www.naturalmachines.com).Within the medical field, for example, researchers at the National University of Singapore have found a way to print customizable tablets that combine multiple drugs in a single tablet, so that doses of medicines are perfectly adapted to the needs of individual patients. 3D printing is also making its mark in the fashion industry, as evidenced by the unveiling at New York Fashion Week in September 2016 of “Oscillation”, a multi-colored 3D-printed dress by threeASFOUR and New York-based designer Travis Finch. Even the agro-food industry is exploring the potential of 3D printing for customized food products.

3D printing is also making its mark in the fashion industry, as evidenced by the unveiling at New York Fashion Week in September 2016 of “Oscillation”, a multi-colored 3D-printed dress by threeASFOUR and New York-based designer Travis Finch. Even the agro-food industry is exploring the potential of 3D printing for customized food products.

Materialise’s consumer 3D printing service, i.materialise, featured in

the fashion show of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp,

Belgium, in 2016. The sunglasses are fully 3D printed “as a total

concept with no need for hinges or assembly” (Photo: Courtesy

of i.materialise.com).

The potential advantages of 3D printing are numerous for innovation-intensive companies. In particular, 3D printing allows them to reduce their overheads when developing, designing and testing new products or improving existing ones. They no longer have to pay for costly prototypes but can rapidly and cheaply undertake multiple iterations of complex elements in-house using 3D printers.

They no longer have to pay for costly prototypes but can rapidly and cheaply undertake multiple iterations of complex elements in-house using 3D printers.

Recognizing the transformative potential of 3D printing, many countries have already adopted, albeit unevenly, different strategies to create an economic and technological ecosystem that favors its development. The European Commission, for example, has identified 3D printing as a priority area for action with significant economic potential, especially for innovative small businesses.

Lawyers in many countries are considering the capacity of existing legal provisions to orient this new technology, particularly with respect to intellectual property (IP). 3D printing technology affects virtually all areas of IP law: copyright, patent law, design law, and even geographical indications. The question is, can IP laws in their current form embrace such an all-encompassing technology or do they need to be reformed? Does existing IP law ensure adequate protection for those involved in 3D printing processes and the products they make? Or would it make sense to consider creating a sui generis right for 3D printing to address emerging challenges, along the lines of arrangements in place in some jurisdictions for the protection of databases?

How current IP law handles 3D printingOne of the main concerns about 3D printing is that its use makes it technically possible to copy almost any object, with or without the authorization of those who hold rights in that object. How does current IP law address this?

How does current IP law address this?

Protecting an object from being printed in 3D without authorization does not raise any specific IP issues as such. Copyright will protect the originality of a work and the creator’s right to reproduce it. This means that if copies of an original object are 3D printed without authorization, the creator can obtain relief under copyright law. Similarly, industrial design rights protect an object’s ornamental and aesthetic appearance – its shape and form – while a patent protects its technical function, and a three-dimensional trademark allows creators to distinguish their products from those of their competitors (and allows consumers to identify its source).

Conventional eyeware design usually begins with the frameinto which corrective lenses are fitted. This can have a negative

impact on lens alignment and performance. With custom

software developed by Materialise, the Yuniku platform uses

3D scanning, parametric design automation and 3D printing to

design the customer’s chosen frame around the optical lenses

they require for a perfect look and fit.

(Photo: Courtesy of i.materialise.com)

Many commentators believe that a 3D digital file may also be protected under copyright law in the same way that software is. The justification for such protection is that “the author of a 3D file must make a personalized intellectual effort so that the object conceived by the author of the original prototype can result in a printed object,” notes French lawyer Naima Alahyane Rogeon. With this approach, the author of a digital file that is reproduced without authorization could claim a moral right in the work if their authorship is called into question. Article 6bis of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, which establishes minimum international standards of protection in the field of copyright, states that the author has “the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation. ”

”

If the printed object is protected by a patent, certain national laws, for example the Intellectual Property Code of France (Article L 613-4), prohibit supplying or offering to supply the means to use an invention without authorization. Following this approach, patent owners should be able to seek redress from third parties for supplying or offering to supply 3D print files on the grounds that these are an “essential element of the invention covered by the patent”.

What is the situation for hobbyists?But what is the situation with respect to hobbyists who print objects in the privacy of their own home? Are they at risk of being sued for infringement?

The standard exceptions and limitations that exist in IP law also naturally apply to 3D printing. For example, Article 6 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS), which has been transposed into EU law (EU Directive 2008/95/CE, Article 5), limits trademark protection to use “in the course of trade”. Similarly, with respect to patent law Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement states that member countries “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent”. Some national laws consider that the rights of the patent holder do not include acts performed in private for non-commercial purposes. In other words, when an object that is protected by a trademark or a patent is printed for purely private use, it is not considered an infringement of IP rights.

Similarly, with respect to patent law Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement states that member countries “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent”. Some national laws consider that the rights of the patent holder do not include acts performed in private for non-commercial purposes. In other words, when an object that is protected by a trademark or a patent is printed for purely private use, it is not considered an infringement of IP rights.

Travis Fitch, 3D printed by Stratasys, a leading 3D print solutions

company based in the United States, was unveiled at New York Fashion

Week in September 2016. “3D printing is transformative for designers

aiming to take complex designs and realize them as a wearable garment,”

explains threeASFOUR’s Adi Gil (Photo: Elisabet Davids, Jan Klier).

In the area of copyright, the rights granted to authors can be limited according to the so-called three-step test. Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement states that “members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.” Accordingly, some countries have established a “right to private copying” authorizing a person to reproduce a work for private use. Countries often then levy a fee on storage devices to compensate any losses incurred by the rights holder; some countries are exploring the idea of levying a fee to offset private 3D copying. However, some lawmakers consider it premature to extend such a fee to 3D printing, as this would constitute “an inadequate response or even a negative message for companies” and would put a brake on the development and uptake of 3D printing.

Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement states that “members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.” Accordingly, some countries have established a “right to private copying” authorizing a person to reproduce a work for private use. Countries often then levy a fee on storage devices to compensate any losses incurred by the rights holder; some countries are exploring the idea of levying a fee to offset private 3D copying. However, some lawmakers consider it premature to extend such a fee to 3D printing, as this would constitute “an inadequate response or even a negative message for companies” and would put a brake on the development and uptake of 3D printing.

IP law in its current form, therefore, appears sufficient to effectively protect both 3D files and those using 3D printing technologies for non-commercial purposes. That said, the specificities of the 3D printing process mean that there are a number of questions that the courts will inevitably need to address. For example, who owns an object when it is first conceived by one individual, digitally modeled by another, and printed by a third? Can the person who designed the work and the person who digitally modeled it be considered co-authors of a collaborative work under copyright law? And if the object qualifies for patent protection, would these same individuals be considered co-inventors?

That said, the specificities of the 3D printing process mean that there are a number of questions that the courts will inevitably need to address. For example, who owns an object when it is first conceived by one individual, digitally modeled by another, and printed by a third? Can the person who designed the work and the person who digitally modeled it be considered co-authors of a collaborative work under copyright law? And if the object qualifies for patent protection, would these same individuals be considered co-inventors?

Other important questions include the type of protection that should be available to owners of 3D printers. Since their financial investment enables the creation of an object, might they qualify for the same type of related rights protection as that enjoyed by music producers whose investment enables the creation of sound recordings? And is the digitization of a pre-existing object considered an act of infringement simply because it is printed or its base file is loaded onto an online sharing platform for downloading? These issues still need to be ironed out.

In the meantime, to curb unauthorized use, if the object is protected by copyright, rights holders can make use of technological protection measures, the circumvention of which is expressly forbidden under the WIPO Copyright Treaty (Article 11). These measures make it possible, for example, to mark an object and its associated 3D print file with a unique identifier to monitor use.

Close collaboration between rights holders and 3D printer manufacturers in applying these measures to models intended for 3D printers could be beneficial. Similarly, partnerships with sharing platforms that make 3D files publicly available could help curb unauthorized use.

With such measures in place, it would be possible to set up a legal offering of downloadable 3D print files or 3D-printed objects. While online 3D printing services such as i.materialise are now readily available, one can imagine that their future evolution will follow that of online music delivery with the emergence of subscription models that allow users to download 3D print files in return for a monthly fee. Indeed, these are already available for 3D printing software, for example through Fusion 360, Autodesk’s cloud-based product innovation platform.

Indeed, these are already available for 3D printing software, for example through Fusion 360, Autodesk’s cloud-based product innovation platform.

Benjamin Hubert from the Layer design agency. The GO

wheelchair prototype was developed in collaboration with

Materialise, a leading 3D print software, engineering

and services provider based in Belgium

(Photo: Courtesy of i.materialise.com).

The experience of online music streaming platforms suggests that such arrangements could have a positive impact on infringement levels. The 2016 Australian Consumer survey on Online Copyright Infringement, for example, showed a 26 percent decrease in the number of Australian internet users accessing unlawful content online and a marked increase in the uptake of streaming services.

3D printing technologies have many life-enhancing, even revolutionary, applications, from regenerative medicine to prosthetics and from complex airplane components to food and fashion. As the use and application of this exciting technology gathers pace and digital transformation continues to gain momentum, 3D printing is likely to become deeply embedded in our daily lives. Beyond the IP-related questions outlined above, the use of 3D printing raises other important legal questions, for example in relation to quality assurance, legal liability and public order. All of these issues still need to be resolved and they can be.

As the use and application of this exciting technology gathers pace and digital transformation continues to gain momentum, 3D printing is likely to become deeply embedded in our daily lives. Beyond the IP-related questions outlined above, the use of 3D printing raises other important legal questions, for example in relation to quality assurance, legal liability and public order. All of these issues still need to be resolved and they can be.

But as the potential of this fascinating technology continues to unfold, the real challenge will be to fully understand the implications of its uptake and use on manufacturing processes across the economy and its impact on our daily lives.

Related Links

- 3D Printing Is Here to Stay!

Copyright and 3D printing / Sudo Null IT News

Looking through the news feed, I came across an interesting article that discusses the legality of copying and distributing three-dimensional models for 3D printers. I, too, have always been interested in the legitimacy of 3D printed replicas. Let's see what Nick Bilton writes about.

I, too, have always been interested in the legitimacy of 3D printed replicas. Let's see what Nick Bilton writes about.

Downloading (often illegal, according to human rights activists) music, movies, books and photos has become so easy that it couldn't be easier. At the same time, there is a whole horde of lawyers fighting copyright infringement, which, however, cannot boast of much success in their field.

Do you think that the current state of affairs is deplorable for authors and creators? Wait until we can copy physical items.

It won't be long before every home has a 3D printer next to its inkjet counterpart. 3D printers, some of which cost less than a computer in 1999, print objects by layering particles of plastic, metal, or ceramic into desired shapes. A person will be able to download a three-dimensional model, click "Print" and after a couple of minutes he will hold the finished item.

Let's call it Industrial Revolution 2.0 . It will not only change production itself, but will also challenge the existing model of ownership and copyright. Suppose that someone really wants the same beautiful mug that a friend has at home. And this someone takes a camera and takes a few pictures. The software processes the photos and our hero already has several of these mugs printed on a 3D printer.

Suppose that someone really wants the same beautiful mug that a friend has at home. And this someone takes a camera and takes a few pictures. The software processes the photos and our hero already has several of these mugs printed on a 3D printer.

Has the law been broken? It looks like it was, but it's not!

What about a floor lamp, a vase, an iPhone case, a board game, a hanger or pieces of furniture? It is highly unlikely that you are breaking the law by copying all of these items.

"Copyright doesn't necessarily protect useful things," says Michael Weinberg, senior lawyer at the Washington digital initiative group. “If an item is purely aesthetic, then it is protected by copyright, but if it can be used to do something, then it is not the kind of thing that can be protected.”

When I told the story about the mug, Weinberg replied, “If you take this mug and go to a clay modeling class and make a similar one, will you ask the same questions? Not". Just because there are new tools like 3D printers and files that allow you to recreate an item faster, it doesn't mean you're breaking the law by using them.

This state of affairs could take design and manufacturing back to the days of the Wild West. This is already happening on Thingiverse, a place where more than 15,000 object schematics are distributed for free. Thomas Lombardi, 3D printer owner and regular contributor to Thingiverse, has uploaded a design for free download called "Lucky Charms Cereal Sifter". This brilliant example of American engineering is a mug with holes in the bottom.

After Lombardi posted his file on Thingiverse, someone downloaded it and posted it elsewhere for $30.

Since the sieve (and this sieve, in fact) is a useful, and not just a decorative thing, Lombardi could not do anything to stop the "pirate".

The recently published research paper of the Palo Alto Institute for the Future, California, "The Future of Manufacturing," states that 3D printing will be a "Big Bang for Manufacturing" as jobs in factories, logistics companies will be replaced by 3D printers, which will be installed in stores to print things on the spot, instead of taking them from somewhere.

Ignoring copyright will accelerate the transition to a new era. Downloading music online is booming as it's an easier way to get music than going to the CD store.

And what would you do, Habraman, would you drag yourself to IKEA on Saturday morning or download a mug from the net?

3D printing - who is responsible for a defective 3D printed item?

For 3D printing, a CAD file (computer-aided design file) must be installed in the printer - a technical drawing that is read by the printer and contains a design of the object to be printed.

3D printing could be a revolutionary technology because it is decentralized and cheap, and in the near future everyone will be able to order 3D printing by sending a CAD file over the Internet to a 3D printing service provider. At the same time, this technology can also cause a number of problems in connection with the verification of the finished product, the possibility of counterfeiting, and risks associated with cybersecurity. From a legal point of view, the main problems are related to the protection of intellectual property rights, as well as the assessment of liability.

From a legal point of view, the main problems are related to the protection of intellectual property rights, as well as the assessment of liability.

Since the whole process is decentralized, this means that one person can design a CAD file, another person can print it, and a third person can use the product. All of this makes it very difficult and confusing to meet security and compliance requirements from a legal standpoint.

Intellectual property rights protection

To properly address the legal issues associated with 3D printing, we must distinguish between (a) the protection of the CAD file (the result of the creative process) and (b) the protection of the finished printed product (the distribution process) . A CAD file consists of data compiled using CAD software (such as AutoCAD). They are usually in .DWG format, which can be imported into a PDF file.

The data cannot be protected by the Copyright Act, only by trade secret protection. In Europe, software protection is provided by copyright. Copyright owner, i.e. the creator can always protect his rights in a way that suits him. The issue of extending copyright protection in relation to a CAD file is questionable if it is not related to artistic creation. Still, the CAD file can be protected by the database sui generis if it can be shown that the collection of the applied data set required significant effort.

In Europe, software protection is provided by copyright. Copyright owner, i.e. the creator can always protect his rights in a way that suits him. The issue of extending copyright protection in relation to a CAD file is questionable if it is not related to artistic creation. Still, the CAD file can be protected by the database sui generis if it can be shown that the collection of the applied data set required significant effort.

During the distribution process, if the physical object is already printed and ready for distribution, the legal approach is different from the analysis applied to the CAD. In this case, copyright protection is no longer valid, and industrial property rights such as patents and design protection provide the most effective protection. Why is this happening? The actual creator of the printed object cannot be the person who orders the machine to print. The creator is the person who created the design/project contained in the CAD file. In the event that a designer/creator wants to extend protection to all creativity and dissemination, this can only be done through a patent or design protection.

Once all the requirements for patent protection (technical development, innovativeness, level of invention and industrial applicability) have been met, the entire process can be patented in the name of its creator, i.e. in this case, the inventor. It is important to note that it is not possible to patent software as such in Europe. The possibility of patenting the functional characteristics of the software is determined by the presence of a technical innovation - the technical level must be different from the current technical level.

The second option for protecting printed objects is design protection, which prevents others from copying a product with the same shape and configuration. For more effective protection, it is important to register the rights to the design.

This means that legal regulations related to 3D printing existed long before the possibility of 3D printing, and they apply to and protect the entire manufacturing process. All legal aspects related to intellectual and industrial property in Europe are suitable for the regulation of such technology. However, the most serious problem is that in each case the solutions are different. For this reason, it is always necessary to analyze each case individually in order to be sure of the rights of the creator/owner/inventor/designer.

However, the most serious problem is that in each case the solutions are different. For this reason, it is always necessary to analyze each case individually in order to be sure of the rights of the creator/owner/inventor/designer.

Considering all the variables associated with 3D printing rights, it is recommended to apply all possible preventive measures so that any individual case can be predicted. In this regard, it is important when licensing rights to have clear, binding terms and a license agreement that will help regulate the resolution of disputes arising in connection with 3D printing. In this way, for example, liability can be waived from the creator of the CAD file.

Consumer Protection

In the case of privately owned 3D printers, there may be a defect liability and/or product warranty issue as between the creator of the CAD file and the end user, there is no manufacturer that could act as an intermediary. This can have serious implications for consumer protection.