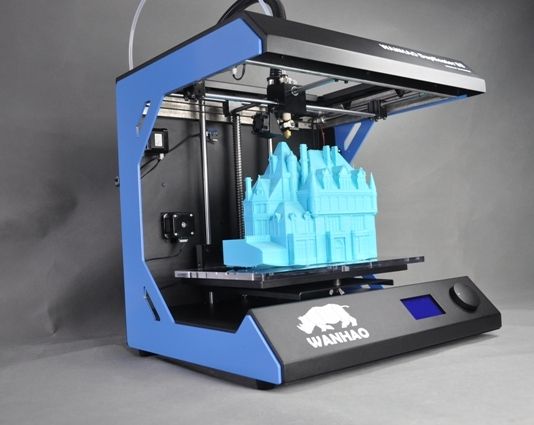

Person of interest 3d printer

What Are 3D-Printed Guns, and Are They Legal?

For decades, weapons manufacturing has been the domain of arms industry heavyweights: Glock, Sig Sauer, Remington, Sturm, Ruger & Co. Making a gun from scratch at home required thousands of dollars of machining equipment and years of engineering expertise.

But in recent years, that has begun to change. Advancements in 3D-printing technology have yielded increasingly reliable 3D-printed firearms, many of which require no federally regulated components to function. Below, we break down the basics of plastic, 3D-printed firearms, and the controversy generated by the swelling movement to deliver them to the masses.

What is a 3D-printed gun?In the simplest terms, it’s any firearm that includes components manufactured with a 3D printer.

But 3D-printed guns vary a lot. Some models — like the 3D-printed gun company Defense Distributed’s “Liberator” — can be made almost entirely on a 3D printer. Others require many additional parts, which are often metal. For example, many 3D-printed gun blueprints focus on a weapon’s lower receiver, which is basically the chassis of a firearm. Under federal law, it’s the only gun part that requires a federal background check to purchase from a licensed dealer. To subvert regulators, some people print lower receivers at home and finish their guns using parts that can be purchased without a background check — metal barrels, for example, or factory buttstocks. Many gun retailers sell kits, which include all the components necessary to assemble a gun at home.

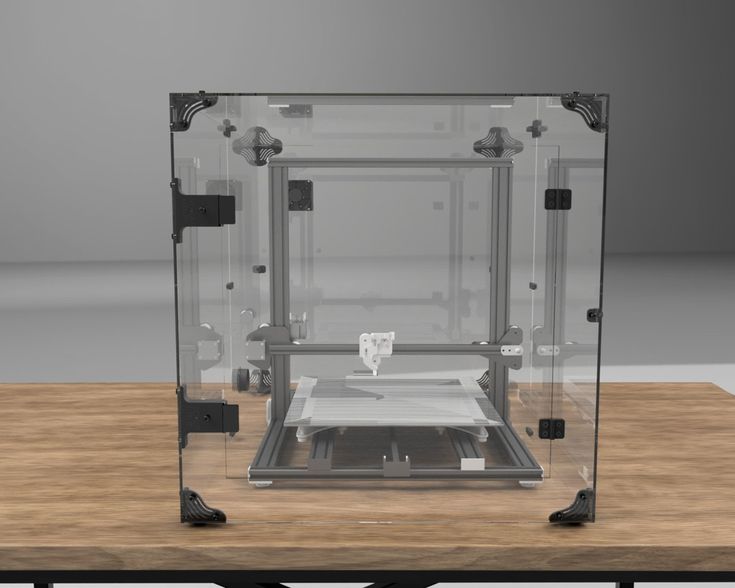

Advances in printing technology have driven the price of 3D printers down — they’re now around $200 on Amazon — and gun groups offer guides for getting started. These developments have lowered the barriers to entry for those in search of untraceable guns, which have turned up at crime scenes with increasing frequency over the past few years.

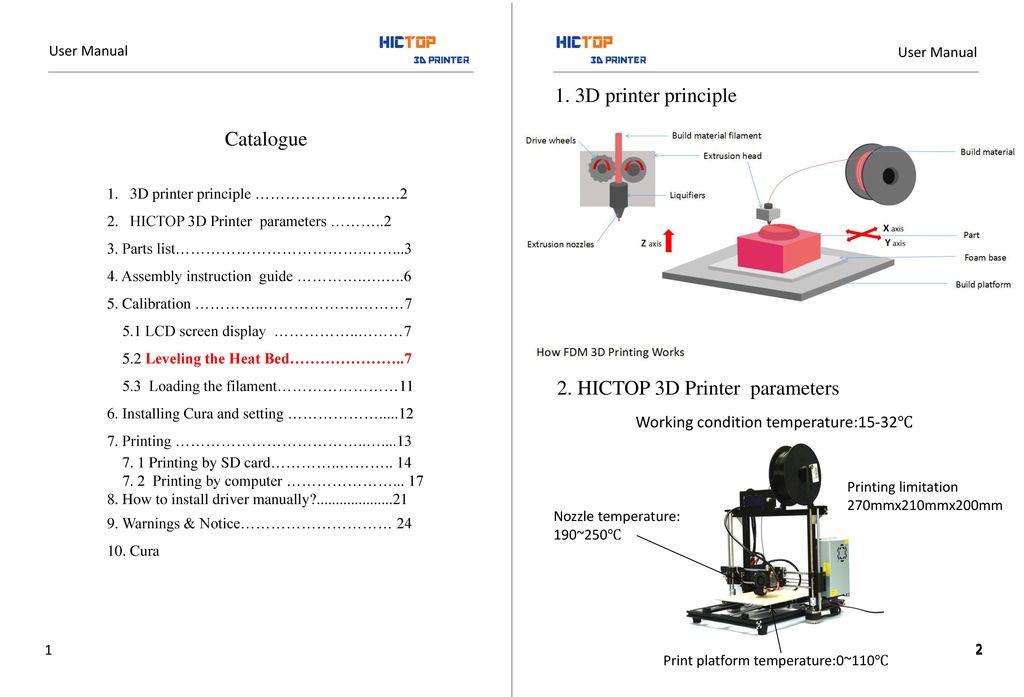

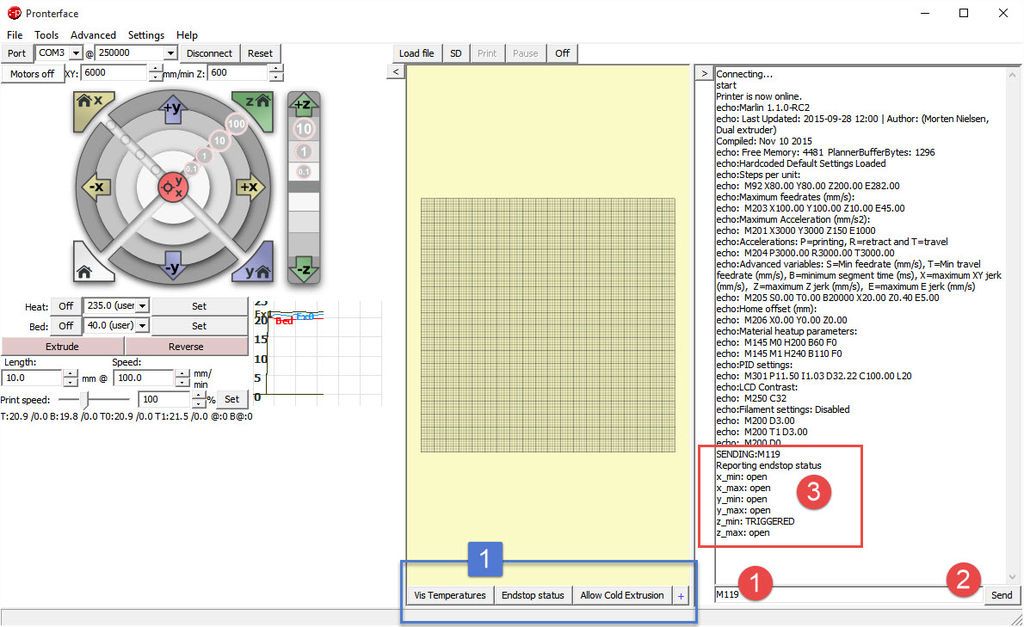

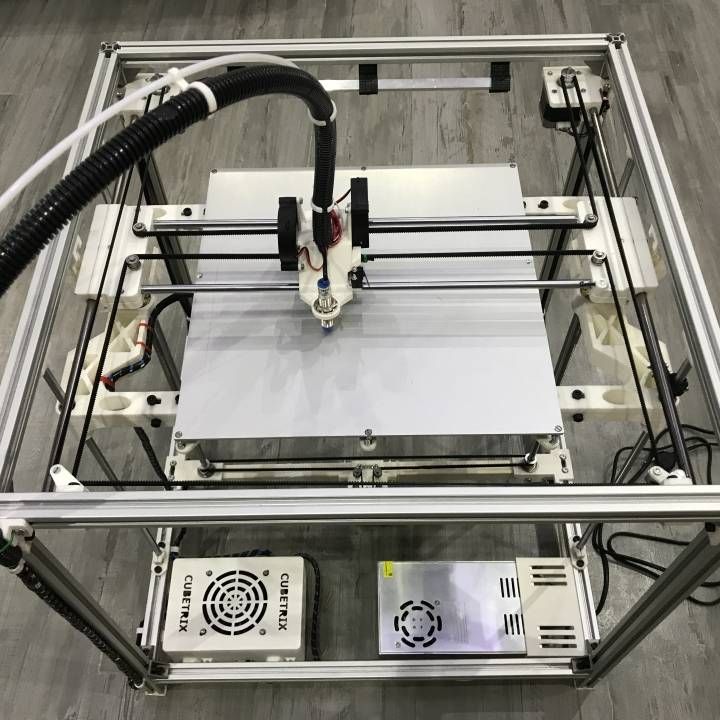

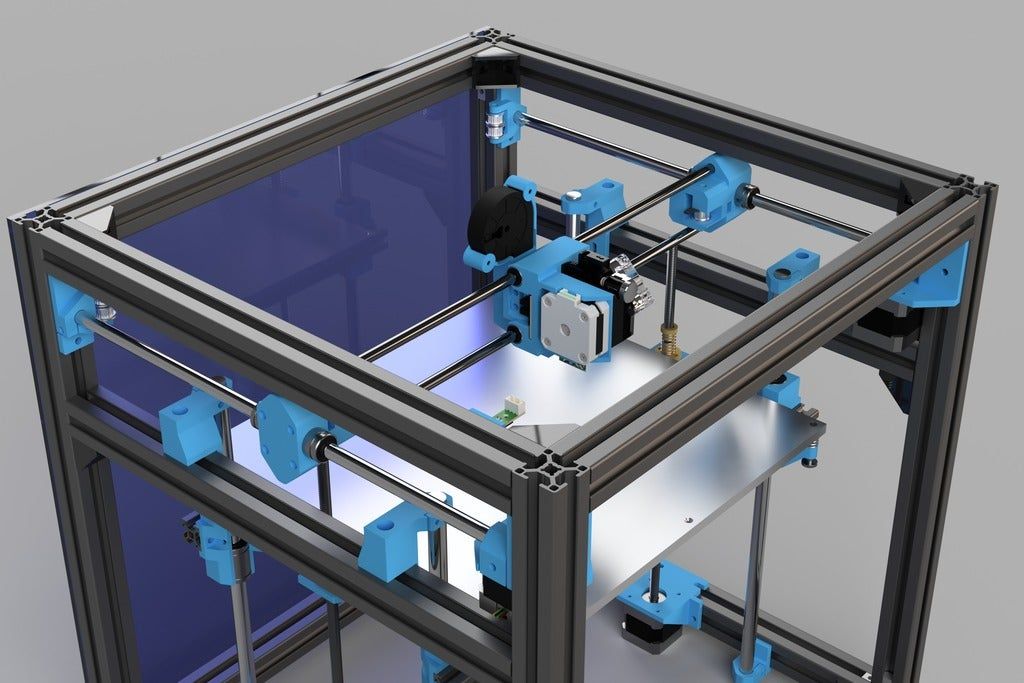

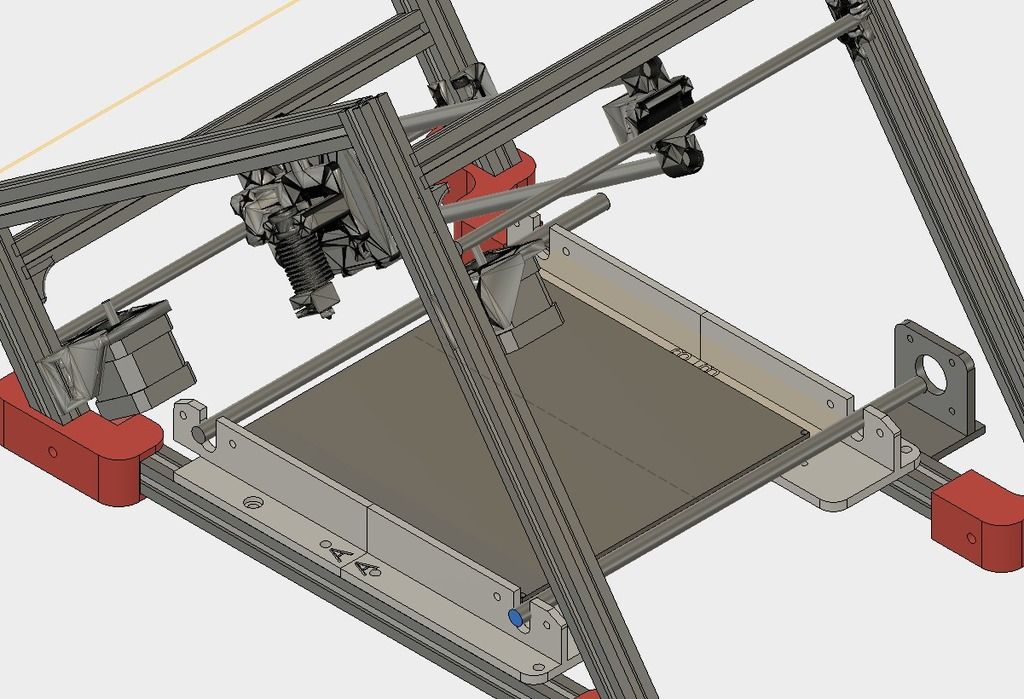

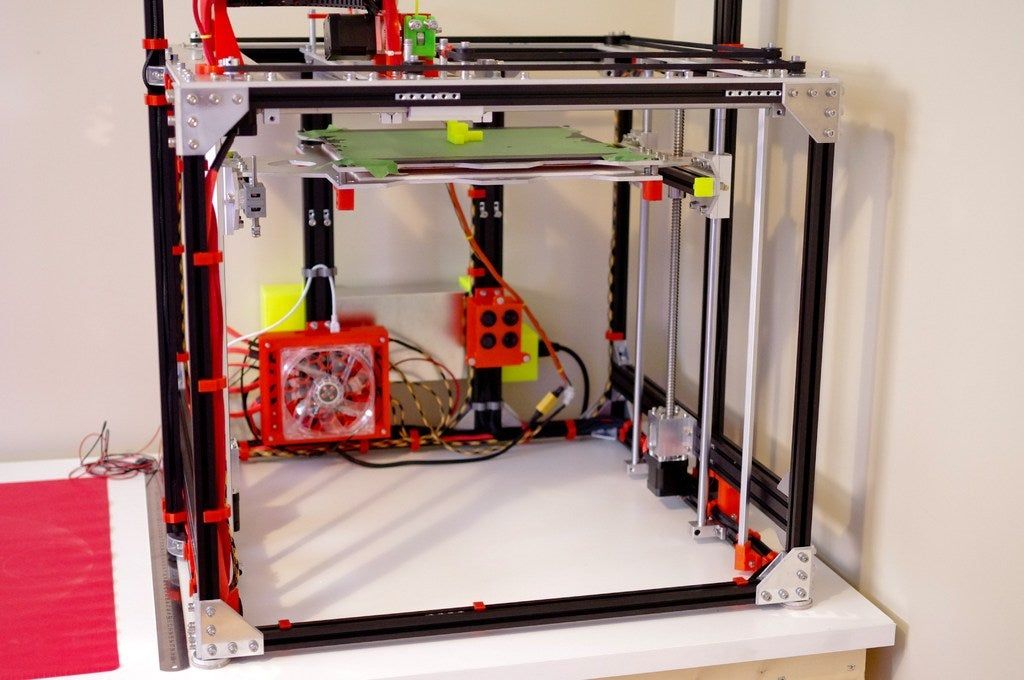

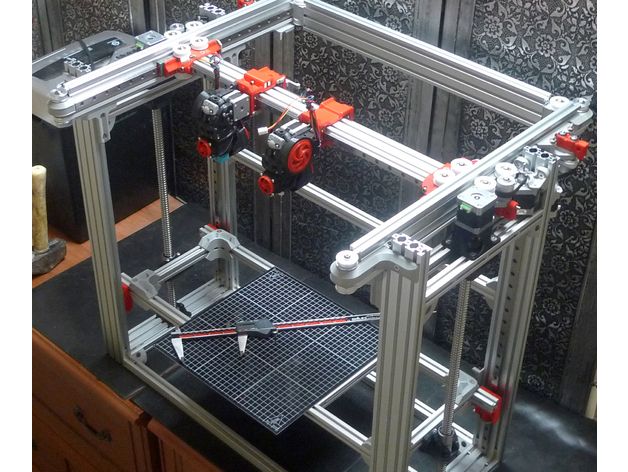

The process still remains more involved than most methods of obtaining a firearm, though. For instance, 3D printers require meticulous setup — the component that extrudes plastic must be calibrated, software must be downloaded to convert designs into 3D-printable slices, and the printer must undergo a slew of upgrades to reliably print weapons parts, which themselves require precise construction to ensure they can contain the explosion from a gunshot.

For instance, 3D printers require meticulous setup — the component that extrudes plastic must be calibrated, software must be downloaded to convert designs into 3D-printable slices, and the printer must undergo a slew of upgrades to reliably print weapons parts, which themselves require precise construction to ensure they can contain the explosion from a gunshot.

Because 3D-printed guns are made outside traditional supply chains, and don’t require background checks, they’re effectively invisible to law enforcement agencies. They are a form of ghost gun: unserialized, and unable to be traced if recovered by law enforcement.

There isn’t good data on the number of 3D-printed firearms that have turned up at crime scenes, though state attorneys general opposed to the technology insist that some have been recovered. On a few occasions, crimes involving the guns have made headlines. In February 2019, police arrested a Texas man after he was found test-firing a 3D-printed gun in the woods. He was prohibited from purchasing firearms and had a hit list of lawmakers on him.

He was prohibited from purchasing firearms and had a hit list of lawmakers on him.

Of particular concern to many law enforcement agencies are guns that can be completely 3D-printed at home without metal components. Politicians and law enforcement professionals fear that such guns would be able to evade metal detectors, and thus slip into places where firearms are prohibited, like airports or government buildings. At present, these fears are largely unfounded — 3D-printed gun designers have yet to develop an alternative to metal bullets, and security officials say that X-ray detection in place alongside most metal detectors can identify the outline of 3D-printed firearms with ease. Indeed, Transportation Security Administration officers have seized 3D-printed firearms at airports on several occasions.

Still, the weapons’ lack of traceability has already caught the attention of terror groups, according to Mary McCord, a former U.S. attorney and prosecutor in the Department of Justice’s National Security Division. “We know from a counterterrorism perspective that there’s great interest among terrorist organizations in being able to have workable, usable, efficient, functioning 3D-printed weapons.”

“We know from a counterterrorism perspective that there’s great interest among terrorist organizations in being able to have workable, usable, efficient, functioning 3D-printed weapons.”

In most cases, yes. Federal law permits the unlicensed manufacture of firearms, including those made using a 3D printer, as long as they include metal components.

In the absence of federal regulation, a handful of states have taken their own steps to clamp down on the creation of homemade guns. In California, anybody manufacturing a firearm is legally required to obtain a serial number for the gun from the state, regardless of how it’s made. In New Jersey, you are supposed to obtain a federal manufacturing license before 3D-printing a gun. The state also criminalizes the manufacture, sale, or possession of undetectable firearms, and made it illegal to purchase parts to make an unserialized gun. Several states — including New Mexico and Virginia — are considering bills that would enact similar restrictions.

The legality of sharing the files required to print guns and gun components is murkier territory. No federal legislation bans the practice. But in 2013, the State Department ruled that releasing blueprints online violated arms export laws. In 2018, after a lengthy court battle with Defense Distributed over the guidance, the State Department settled, and agreed to permit the files’ release. But before the prohibition was lifted, a coalition of states sued to keep it in place — and won. Now, gun groups intent on sharing the files online have exploited a loophole in the State Department’s policy, which allows for the distribution of blueprints exclusively to U.S. residents. Defense Distributed maintains it has established a vetting procedure to ensure only U.S. residents are able to download them.

In 2019, the Trump administration transferred oversight of gun exports from the State Department to the Commerce Department, which would have rolled back restrictions on releasing 3D-printed gun blueprints. But a second suit filed by the coalition of state attorneys general has kept oversight of the files with the State Department, pending future litigation.

But a second suit filed by the coalition of state attorneys general has kept oversight of the files with the State Department, pending future litigation.

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal is a plaintiff in the case. “If a company like Defense Distributed can simply sell printable [gun blueprints] to their customers without running the usual required background checks to make sure someone’s not a criminal, it would blow up the entire regime of firearm laws that we have in this country,” he said.

In 2019, after Grewal sought an injunction to block Defense Distributed from releasing files to New Jersey residents, the company countersued. It alleges that the blueprint files are a form of speech, and that Grewal’s effort to block their release violates the First Amendment. The case has yet to go to trial.

Who is printing guns — and why?The first 3D-printed firearm to make a splash in the popular consciousness was the “Liberator” — a near fully plastic gun designed by a self-described anarchist and ghost-gun advocate named Cody Wilson. (Designs for the Liberator call for a small steel block to be sealed inside the plastic in order to comply with federal law.) Wilson founded Defense Distributed to advance and share the technology, and has initiated many of the group’s highest profile legal battles. In 2019, Wilson was sentenced to probation and ordered to register as a sex offender after soliciting sex from a minor.

(Designs for the Liberator call for a small steel block to be sealed inside the plastic in order to comply with federal law.) Wilson founded Defense Distributed to advance and share the technology, and has initiated many of the group’s highest profile legal battles. In 2019, Wilson was sentenced to probation and ordered to register as a sex offender after soliciting sex from a minor.

Though Wilson’s is the best-known and formally recognized gun printing “company,” the practice is mostly advanced by informal collectives across the internet. These groups, like Deterrence Dispensed and Fosscad, gather anonymously in chat rooms and on social media platforms to crowdsource the development of new gun designs and spread them across the web. They have thousands of members, but remain mostly decentralized, making it difficult for technology companies or law enforcement agencies to police them.

Over the past two years, however, the groups have run up against censorship policies at major tech platforms, many of which prohibit weapons content. As a result, they’ve been forced to increasingly obscure corners of the internet. Most recently, the operations hub for most of the 3D-printed gun groups — an encrypted chat and file-sharing platform called Keybase — pledged to remove all weapons-related content, and told the groups they would be banned.

As a result, they’ve been forced to increasingly obscure corners of the internet. Most recently, the operations hub for most of the 3D-printed gun groups — an encrypted chat and file-sharing platform called Keybase — pledged to remove all weapons-related content, and told the groups they would be banned.

Proponents of the technology fall into several different camps. Some, like Mustafa Kamil, a creator of 3D-printable guns based in Romania, and a member of the Deterrence Dispensed team on Keybase, think that concerns over homemade weapons are overblown. Gun printing, he says, is mostly the domain of hobbyists like himself: technical experts interested in tinkering and engineering. To 3D-print a gun: “you need to have enough money to buy a printer. Then you need enough expertise and experience to know how to use the printer. If your axis is off by 0.15 millimeters the gun isn’t going to work,” he said. “To buy a black market firearm would be much easier.” Kamil said he’s owned 32 printers and completed two apprenticeships with gun manufacturers.

Others see the potential for armed conflict with the government as the driving force behind their creations. Members of Deterrence Dispensed and Defense Distributed have fashioned a brand out of this perceived threat, adopting popular Second Amendment slogans like “Come and Take It,” “Live Free or Die,” and “Free Men Don’t Ask.” Leaders of the groups share a deep conviction that gun ownership is the only way to ensure freedom: In an interview with Popular Front, a conflict journalism outfit, the founder of Deterrence Dispensed — a man who goes by the username jstark — continuously pointed to the threat of government tyranny as a justification for creating 3D-printed guns and distributing their blueprints. “Just look at the Uighurs in China,” he said, referring to the ongoing genocide of the ethnic minority. “Just look what’s happening to them. No one’s helping them. Nobody does shit. You know what would help them? If they were armed. That would be a deterrence.”

To jstark, identical threats exist anywhere where civilians are largely unarmed, including in Europe, where he lives. When asked if he would fight police who tried to confiscate his guns, he was frank: “Basically, yes. Live free, or die. These are not empty words.”

When asked if he would fight police who tried to confiscate his guns, he was frank: “Basically, yes. Live free, or die. These are not empty words.”

While politicians and law enforcement agencies have dubbed the advocates of 3D-printed firearms extremists, the movement has no unifying political ideology. Jstark, for his part, said in the Popular Front interview that Deterrence Dispensed has no tolerance for people who wish to harm others: “If they do show through [their actions] that they’re extremists, racists, islamic terrorists — then we would kick them out immediately,” he said. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The alarmism about about looming government tyranny has attracted groups eager to ignite government conflict, particularly in the U.S. Members of groups connected to the boogaloo, a loose-knit coalition of anti-government extremists that advocates a violent civil war, have seen 3D-printed gun advocates as allies in an overlapping struggle. Last summer, Megan Squire, a professor at Elon University, tracked online boogaloo-connected groups as they navigated crackdowns from social media platforms. Many ended up on Keybase, drawn by the large and growing 3D-printed gun community.

Last summer, Megan Squire, a professor at Elon University, tracked online boogaloo-connected groups as they navigated crackdowns from social media platforms. Many ended up on Keybase, drawn by the large and growing 3D-printed gun community.

In early April, Deterrence Dispensed released blueprints for a printable auto sear — a component that can be used to turn a semiautomatic rifle into an illegal, fully automatic firearm — called the “Yankee Boogle,” an apparent boogaloo reference. In September, two boogaloo adherents were charged for allegedly attempting to sell auto sears to representatives of Hamas, the Islamist extremist group. In court documents, prosecutors alleged that one of the defendants in that case said he obtained the auto sears from a supplier who 3D-printed them. In a separate case, federal prosecutors charged a man from West Virginia with 3D-printing auto sears and selling more than 600 of them online, including to several boogaloo adherents. One man who bought the 3D-printed auto sears is accused of killing a police officer and a security guard in California. It is unclear if any of the auto sears used in these crimes were designed by Deterrence Dispensed.

It is unclear if any of the auto sears used in these crimes were designed by Deterrence Dispensed.

Correction: An earlier version of this article highlighted a case in which police in Rhode Island said a suspect used a 3D-printed gun in a murder. While police initially made that claim, an analysis by the state crime lab later ruled the method of manufacture “undetermined.” The story has also been updated to include that Defense Distributed’s “Liberator” gun model includes a small metal component for federal compliance.

Working gun made with 3D printer

Published

comments

Comments

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Media caption,The BBC's Rebecca Morelle saw the 3D-printed gun's first test in Austin, Texas

By Rebecca Morelle

Science reporter, BBC World Service, Texas

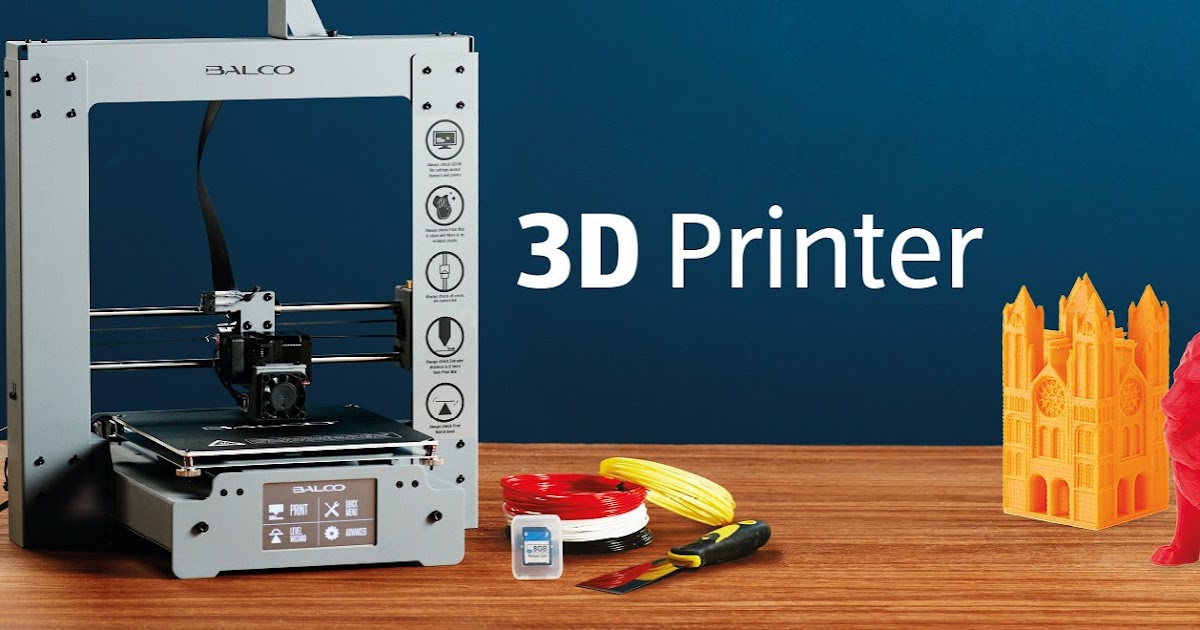

The world's first gun made with 3D printer technology has been successfully fired in the US.

The controversial group which created the firearm, Defense Distributed, plans to make the blueprints available online.

The group has spent a year trying to create the firearm, which was successfully tested on Saturday at a firing range south of Austin, Texas.

Anti-gun campaigners have criticised the project.

Europe's law enforcement agency said it was monitoring developments.

Victoria Baines, from Europol's cybercrime centre, said that at present criminals were more likely to pursue traditional routes to obtain firearms.

She added, however: "But as time goes on and as this technology becomes more user friendly and more cost effective, it is possible that some of these risks will emerge."

Defense Distributed is headed by Cody Wilson, a 25-year-old law student at the University of Texas.

Mr Wilson said: "I think a lot of people weren't expecting that this could be done."

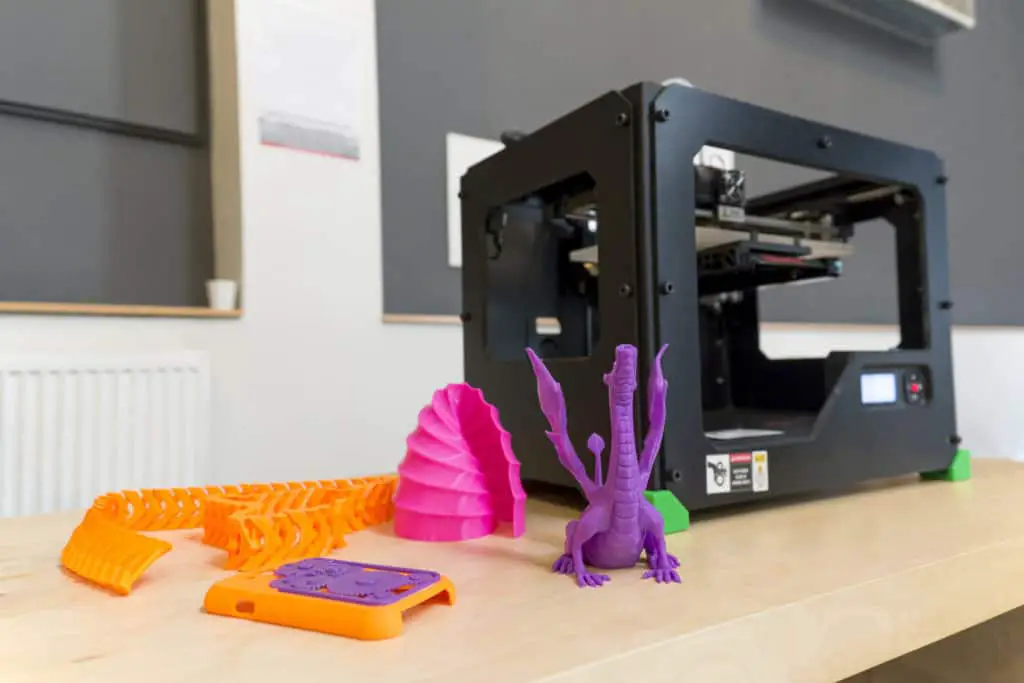

Image caption,The gun was assembled from separate printed components made from ABS plastic - only the firing pin was made from metal

3D printing has been hailed as the future of manufacturing.

The technology works by building up layer upon layer of material - typically plastic - to build complex solid objects.

The idea is that as the printers become cheaper, instead of buying goods from shops, consumers will instead be able to download designs and print out the items at home.

But as with all new technologies, there are risks as well as benefits.

Personal liberties

The gun was made on a 3D printer that cost $8,000 (£5,140) from the online auction site eBay.

It was assembled from separate printed components made from ABS plastic - only the firing pin was made from metal.

Mr Wilson, who describes himself as a crypto-anarchist, said his plans to make the design available were "about liberty".

He told the BBC: "There is a demand of guns - there just is. There are states all over the world that say you can't own firearms - and that's not true anymore.

"I'm seeing a world where technology says you can pretty much be able to have whatever you want. It's not up to the political players any more."

It's not up to the political players any more."

Asked if he felt any sense of responsibility about whose hands the gun might fall into, he told the BBC: "I recognise the tool might be used to harm other people - that's what the tool is - it's a gun.

"But I don't think that's a reason to not do it - or a reason not to put it out there."

Gun control

To make the gun, Mr Wilson received a manufacturing and seller's licence from the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

Donna Sellers, from the ATF, told BBC News that the 3D-printed gun, as long as it was not a National Firearms Act weapon (an automatic gun, for example), was legal in the US.

She said: "[In the US] a person can manufacture a firearm for their own use. However, if they engage in the business of manufacture to sell a gun, they need a licence."

Amid America's ongoing gun debate in the wake of the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, US congressman Steve Israel recently called for a ban on 3D guns under the Undetectable Firearms Act.

Groups looking to tighten US gun laws have also expressed concern.

Leah Gunn Barrett, from New Yorkers Against Gun Violence, has said: "These guns could fall into the hands of people who should not have guns - criminals, people who are seriously mentally ill, people who are convicted of domestic violence, even children."

3D printing technology has already been used by some criminal organisations to create card readers - "skimmers" - that are inserted into bank machines.

Many law enforcement agencies around the world now have people dedicated to monitoring cybercrime and emerging technologies such as 3D printers.

Ms Baines from Europol said: "What we know is that technology proceeds much more quickly than we expect it to. So by getting one step ahead of the technological developments, we hope and believe we will be able to get one step ahead of the criminals as well."

About what you can print on a 3D printer / Habr

Sergiv

Reading time 2 min

Views12K

3D printers

Recovery mode

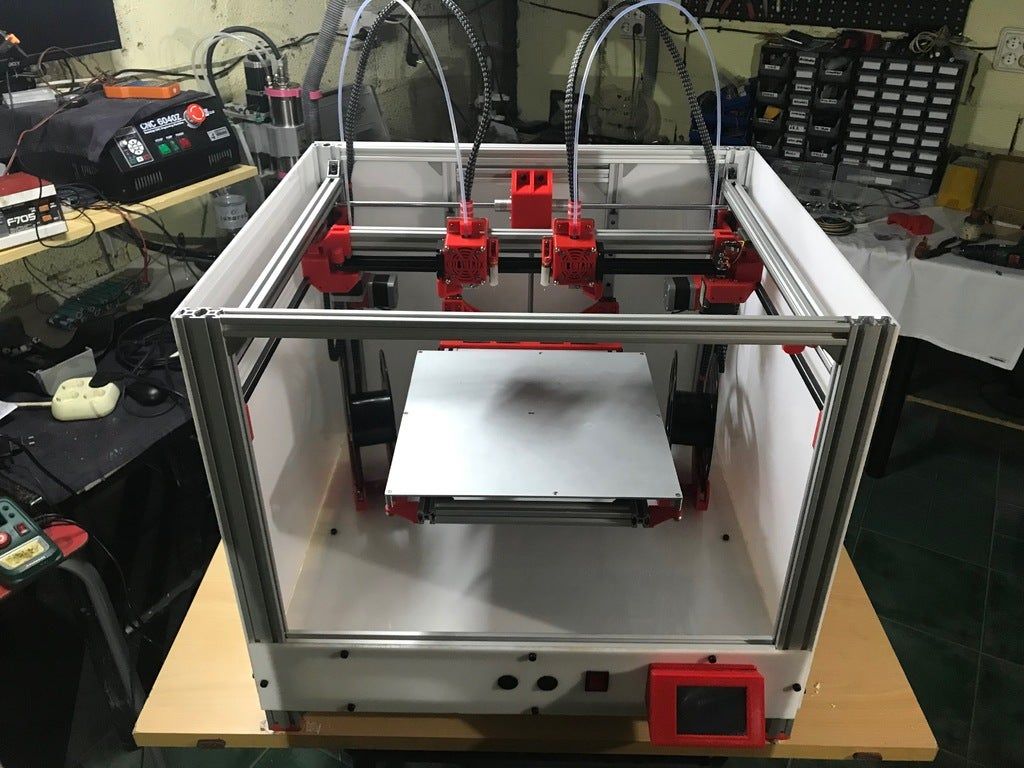

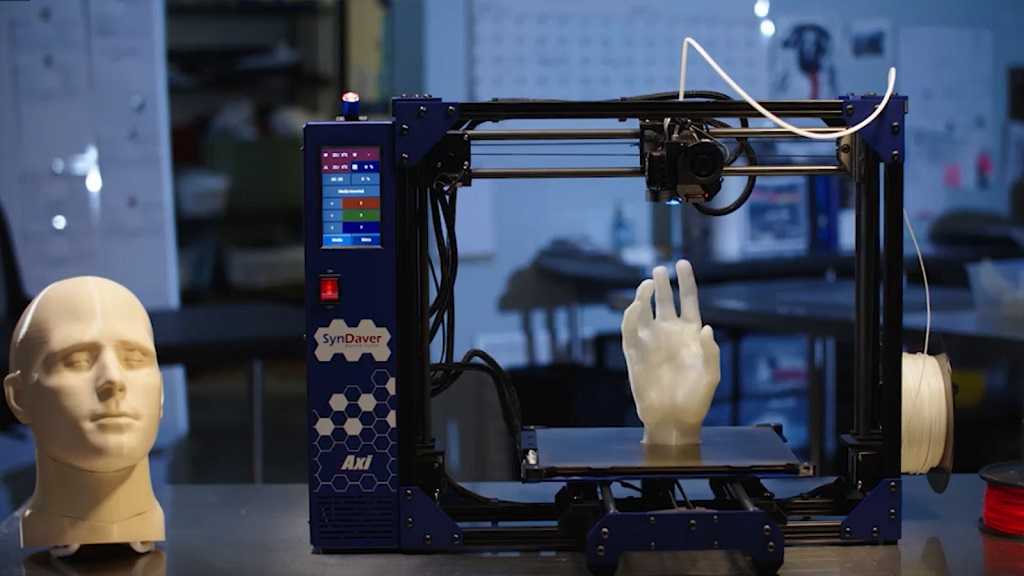

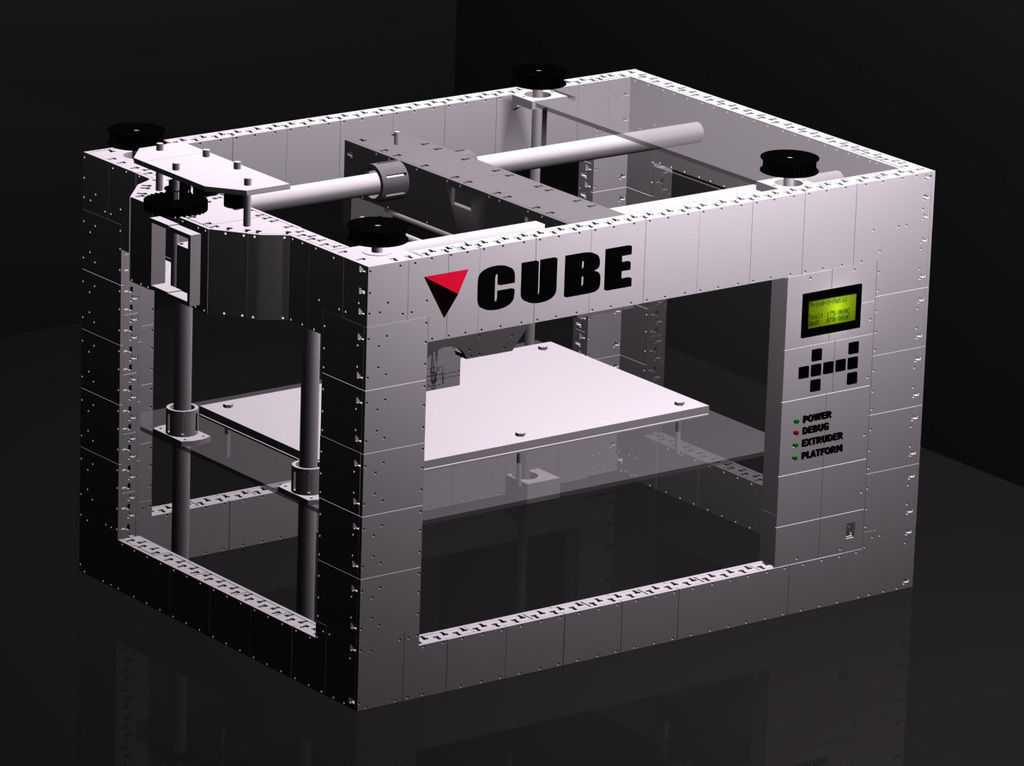

Hello everyone. My name is Sergey and I am engaged in the development of 3D printers. In this article, I want to show you how to use the RK-1 personal SLA 3D printer (with photos, of course).

When someone is asked what a 3D printer can be used for, many people immediately remember jewelry production. Let's start with her. The polymer is not cast (you can, of course, pour directly from it, but there are nuances). However, many jewelers do without casting polymer - they make molds and pour wax into them, getting waxes. I will describe this method in more detail in future articles.

Prototyping will be the next application. It is also an important and widespread use of a 3D printer. We print the device under development, see how it is assembled (yes, you can do it in CADe, see how it lies in your hand, on a table, in your pocket, etc. , install electronics. Or just print a reduced layout of the product under development for demonstration to a customer or another interested party

, install electronics. Or just print a reduced layout of the product under development for demonstration to a customer or another interested party

Let's not ignore the use of a 3D printer for medical purposes. In this case, for example, I cite the printing of surgical templates. Earlier in the article I described in more detail what it is and why.

There are such products - collectible celebrity figurines. Previously, heads for such products were sculpted (maybe they are still sculpting) with hands from plastic masses. Now they are molded in a 3D modeling program and then printed. It remains only to cover with primer and paint.

3D printers are generally more profitable and convenient to use in cases where you need to print one product and then make copies of it. Yes, of course, there are examples when mass-produced products are printed immediately, but this is not so common now. In general, the technology is simple: we print the product, remove the mold, pour the material into the mold.

Print results:

Cast results:

Printing of various products, layouts, figurines, cases, etc. These are just the products that are needed in a single version without the need for replication.

Thank you all for your attention. What application do you see for a 3D printer?

Tags:

- 3d printing

- sla

- 3d printer

- RK-1

- 3d printing application

Hubs:

- 3D printers

Total votes 18: ↑14 and ↓4 +10

Comments thirty

Sergey @Sergiv

User

Comments Comments 30

Building a house with a 3D printer: an overview of companies and prospects

Construction 3D printing is one of the most controversial, but rapidly developing areas in the field of additive technologies. Engineers from all over the world compete to create 3D mortar printers, with designs ranging from humble, hastily built sheds to high-rise buildings.

Engineers from all over the world compete to create 3D mortar printers, with designs ranging from humble, hastily built sheds to high-rise buildings.

Today we pay tribute to the most famous names in the field of additive construction technologies and try to understand what 3D construction printing is, how it is used, and what to expect in the future.

Contour Crafting

Professor Beroch Khoshnevis is considered one of the founders of modern construction 3D printing technologies. A native of Iran, Beroch moved to the US and is currently on the dean's office at the University of Southern California (USC) and works closely with NASA. Professor Koshnevis is the author of the Contour Crafting technology, which in one way or another served as the basis for alternative developments: the mortar is applied using an extruder mounted on a movable portal structure.

The full version of the technology provides for a fully automated process, including the installation of fixtures and communications during printing using robotic arms. Work on the technology has been underway since 1995, but there are few practical results, or they are kept secret. The fact is that one of the sponsors of the research is the US Navy, which is interested in the technology of automated construction of military bases. Since 2010, NASA has also become interested in the team's developments, in need of a suitable methodology for building lunar and Martian colonies.

Work on the technology has been underway since 1995, but there are few practical results, or they are kept secret. The fact is that one of the sponsors of the research is the US Navy, which is interested in the technology of automated construction of military bases. Since 2010, NASA has also become interested in the team's developments, in need of a suitable methodology for building lunar and Martian colonies.

Koshnevis, however, managed to accuse the Chinese construction company WinSun of stealing technology ( see below ), which is rapidly strengthening its position in the commercial market.

D-Shape

One of the more unusual construction 3D printing designs, designed by Italian engineer Enrico Dini. Unlike competitive setups, the D-Shape 3D printer does not use a 3-axis positionable extruder, but relies on a whole array of 300 nozzles mounted on a moving platform.

The working area in the current version is 6x6 meters. The technology is more like inkjet printing, and the array is used to apply a binding agent to layers of sand. The first printer model, patented in 2006, printed with epoxy resins, but this approach caused a lot of technical difficulties and was abandoned. A new version, patented in 2008, uses metal oxides and magnesium chloride as binders.

Theoretically, the technology allows to achieve high printing speed, but in practice there are limitations due to the slow curing of the material - it takes about one day for full setting. On the other hand, the residual material acts as a support, partially removing the mechanical load from the fresh layers. Although Dini does not leave hopes for the commercialization of his technology, the most impressive example of practical printing so far remains a one-piece sculpture called "Radiolaria" measuring 3x3x3 meters.

"StroyBot" by Andrey Rudenko

Andrey Rudenko rightfully takes the place of one of the pioneers of construction 3D printing. A talented engineer who moved to Minnesota, he first attracted attention with the project of a miniature fairy-tale castle, made using a 3D printer of his own design called StroyBot.

The path of the developer turned out to be thorny, and the main problems are not technology, but the ubiquitous bureaucracy. Faced with a red tape in the US and no illusions about the Russian market, Andrey found support in Lewis Yakic, a Californian entrepreneur and owner of the Philippine Lewis Grand Hotel.

It was there that Rudenko demonstrated the full potential of his technology by printing a 130m² extension with several bedrooms, all necessary communications and even a jacuzzi ( see video below ).

Geopolymer concrete made from volcanic ash was used as a consumable. The project is also unique in that the hotel wing has become the world's first operational 3D printed object. More information about Andrey Rudenko's developments can be found in the inventor's personal blog on 3Dtoday.

Spetsavia

Spetsavia has been much more fortunate in the Russian market. For several years now, the Yaroslavl enterprise, which initially specialized in the production of CNC machines for the metalworking industry, has been designing construction 3D printers. To date, the company's range consists of at least seven options of different sizes.

The most famous project using the Spetsavia 3D printer was the construction of an unusual gatehouse on the territory of the Yekaterinburg Cement Plant: the director of the enterprise, Rinat Brylin, who has been fond of 3D printing since his student years, decided to place the plant’s guards in a replica of the tower of Winterfell Castle from the popular television series “Game Thrones". The construction of an unusual building, printed using the S-6044 Long 3D printer, was completed in November last year. The cooperation between Brylin and Spetsavia is mutually beneficial, because having a 3D printer on hand, plant employees can test special building mixtures “on the spot”.

In 2016, the company sold about three dozen building 3D printers, and this year it is going to demonstrate full-scale projects: in December 2015, the company's specialists for the first time printed a full-fledged building with an area of 165 square meters. meters. Various technologies were used during construction, part of the building was printed directly on the site, and some blocks were printed in the workshop before being delivered to the site and assembled.

Fixed formwork was reinforced during printing. After assembly, the load-bearing elements of the walls were poured with concrete produced by the Yekaterinburg cement plant mentioned above, and the outer contour was insulated with foam-gypsum concrete from the Monolith plant. According to the plans of the owner, the finishing of the building will be completed this summer, after which the project will be demonstrated to the public.

Apis Cor

Spetsavia also has an interesting, promising competitor in the person of the Irkutsk company Apis Cor. If Spetsavia 3D printers, like most competitors, use a portal scheme, the development of Apis Cor is based on the use of a telescopic manipulator on a turntable. In other words, the printer builds walls around itself, and when completed, is transported to another location with a crane. Designed from the outset for high mobility: the compact six-ton unit fits easily into a truck.

The first full-fledged demonstration of the capabilities of an unusual 3D printer was the construction of an experimental building in Stupino, which was completed a month ago. The unusual rounded shape of the house with an area of 37 square meters. meters clearly demonstrates the architectural flexibility of building 3D printing. It took less than a day to build the walls, but it took about a month to fully harden. It should be noted that the project was carried out in not the most favorable weather conditions, which is why the object had to be erected under an awning.

The building is equipped with thermal insulation and all necessary communications, but no one will live in it, because this building is intended purely for demonstration purposes. Next up is a larger-scale project: building two demonstration houses in Texas, and then building an eco-village with local construction company Sunconomy.

WinSun

And finally, the most famous enterprise in the industry is the Chinese company WinSun. In 2014, a Shanghai-based company became famous throughout the world by erecting ten 3D printed buildings in just one day. In fact, everything turned out to be a little more modest: small “boxes” were printed block by block in the workshop, and then assembled at the construction site without fittings or communications, but with glazing. However, a start has been made. In less than a year, Chinese builders have already distinguished themselves by the most ambitious project to date, or rather two at once - a 3D-printed five-story building and a pretty mansion with an area of 1100 sq. meters.

The company's efforts did not go unnoticed: by 2016, WinSun representatives were negotiating huge contracts with the authorities in Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Iraq needs to build about ten thousand houses to replace those destroyed during the war, and the Saudis are interested in printing one and a half million buildings at once to solve the growing housing crisis. Nothing is known about firm contracts yet, but from time to time the company reminds of itself, for example, the construction of the first 3D-printed office building in Dubai.

The "Office of the Future" was built in just 17 days, including communications wiring, finishing and furnishing. Construction of a 250 sq. meters, a team of eighteen people was engaged, and only one operator looked after the printer. After completion of construction, the building housed the office of the Dubai Future Foundation. The WinSun 3D printer is a portal structure with dimensions of 36x12x6 meters, and building mixtures with fillers from recycled waste, most likely fiberglass, are used as consumables.

Prospects for building 3D printing

So what is the potential of building additive technologies? It must be understood that this is not a panacea, not a replacement for traditional building technologies, but a useful addition. The practical use of building 3D printing so far comes down to the production of various decorative elements and fixed formwork of complex shapes: if WinSun’s architectural projects are not particularly original, the Apis Cor demonstration building in Stupino, Rudenko’s spiral columns and 3D printed church domes of Spetsavia clearly demonstrate design freedom.

The issue of reinforcement and insulation is solved quite simply: as the layers are printed, horizontal reinforcement is laid, after the 3D-printed formwork hardens, communications are installed, and the internal volume is filled with additional reinforcement, insulation and poured with concrete in accordance with the project. The outer surface of the walls is sanded and / or plastered. As a result, significant savings are achieved on the removable formwork and, most importantly, labor. The latter point can have a key impact on the pace of development of construction 3D printing in different regions of the world, because the attractiveness of such automation is directly proportional to the high cost of labor.

Fully automated additive construction technologies do not yet exist, except for the theoretical developments of Contour Crafting: pouring the foundation and installing reinforcement, communications and floors still has to be done manually. On the other hand, nothing prevents us from shifting these tasks onto the shoulders of robots. For example, engineers from ETH Zurich have already demonstrated a welding robot capable of creating rebar of various shapes, the Dutch company MX3D is working on a 3D-printed all-metal bridge project in Amsterdam, and the Australian company Fastbrick Robotics is designing brick laying robots.

3D printed skyscrapers are not worth the wait. In the coming years, building additive technologies will be used mainly for the manufacture of decorative elements and relatively small design objects. The scale of application will directly depend on the cost of materials, labor and even geographical location.