Background of 3d printing

When Was 3D Printing Invented? The History of 3D Printing -

May 15, 2020

When you first heard the words “3D printing” did you imagine a super futuristic technology, like in the movies but, when was it really invented?

While the term 3D printing may sound like something you’d expect to hear in a science fiction novel, the history of 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is longer than you might think.

Keep reading to learn about the history of 3D printing, and our BCN3D predictions on where we see this technology going in the future.

The History of 3D Printing in 3 PhasesThe 1980s: When Was 3D Printing Invented?The first documented iterations of 3D printing can be traced back to the early 1980s in Japan. In 1981, Hideo Kodama was trying to find a way to develop a rapid prototyping system. He came up with a layer-by-layer approach for manufacturing, using a photosensitive resin that was polymerized by UV light.

Although Kodama was unable to file the patent requirement of this technology, he is most often credited as being the first inventor of this manufacturing system, which is an early version of the modern SLA machine.

Across the world a few years later, a trio of French researchers was also seeking to create a rapid prototyping machine. Instead of resin, they sought to create a system that cured liquid monomers into solids by using a laser.

Similar to Kodama, they were unable to file a patent for this technology, but they are still credited with coming up with the system.

That same year, Charles Hull, filed the first patent for Stereolithography (SLA). An American furniture builder who was frustrated with not being able to easily create small custom parts, Hull developed a system for creating 3D models by curing photosensitive resin layer by layer.

In 1986 he submitted his patent application for the technology, and in 1988 he went on to found the 3D Systems Corporation. The first commercial SLA 3D printer, the SLA-1, was released by his company in 1988.

The first commercial SLA 3D printer, the SLA-1, was released by his company in 1988.

But SLA wasn’t the only additive manufacturing process being explored during this time.

In 1988, Carl Deckard at the University of Texas filed the patent for Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) technology. This system fused powders, instead of liquid, using a laser.

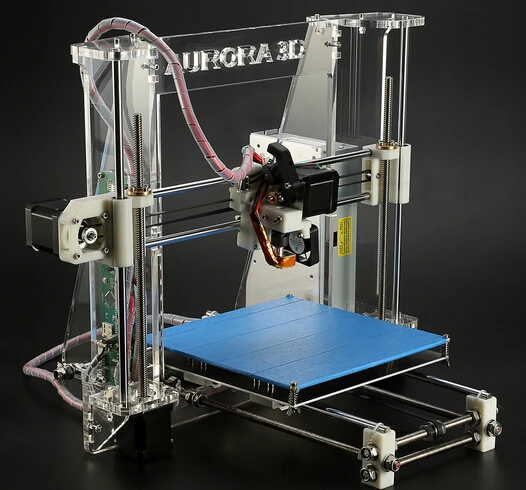

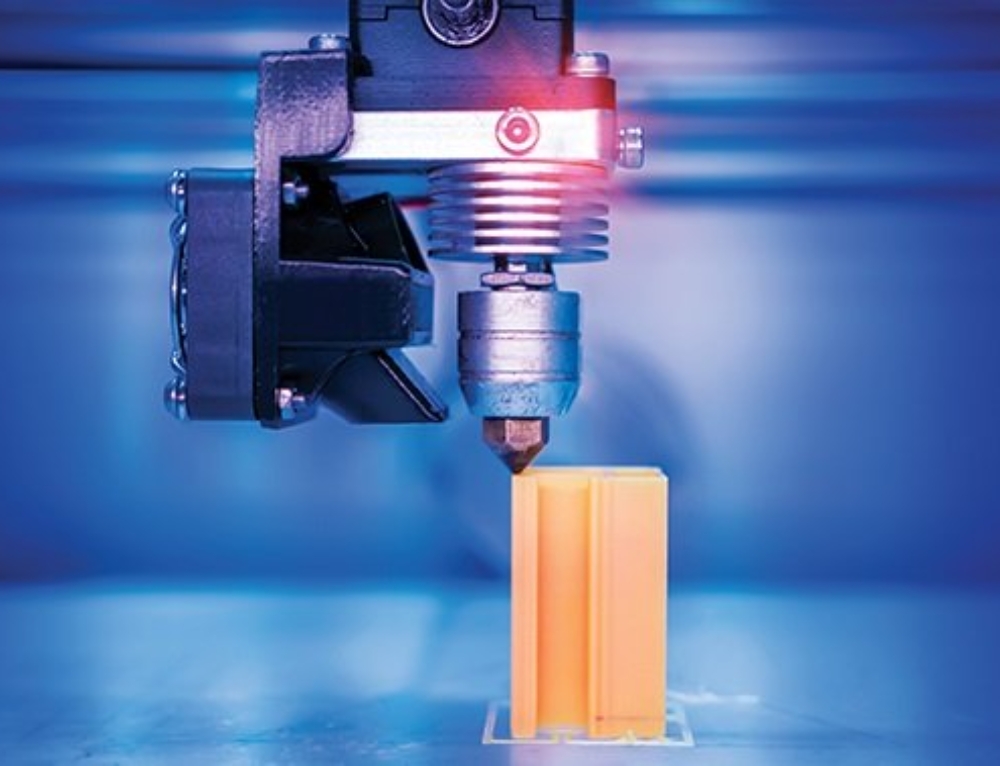

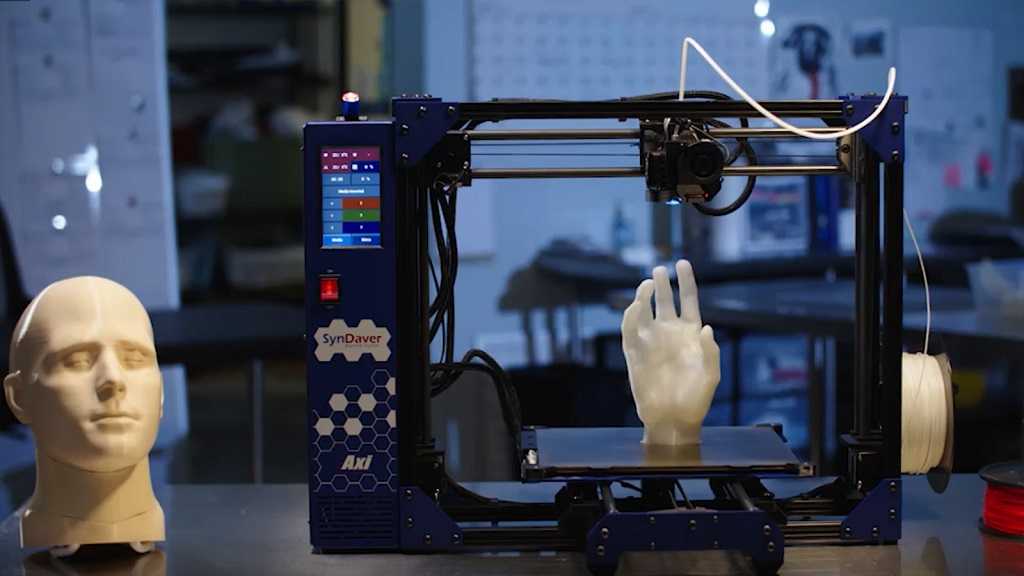

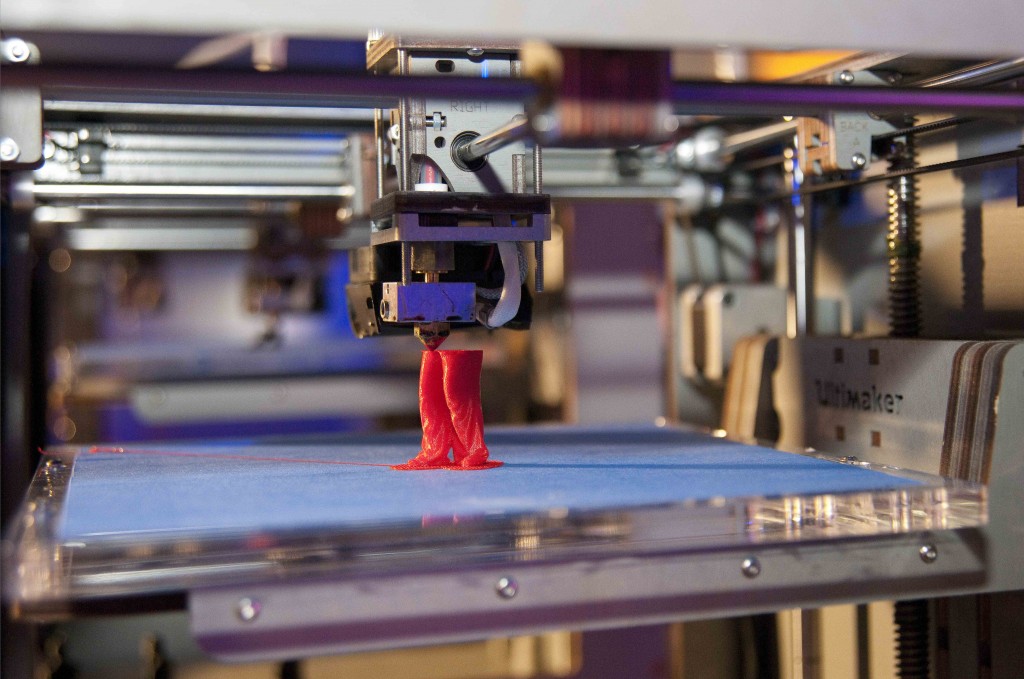

SLS fabrication machines in the Fundació CIM warehouseFused Deposition Modeling (FDM) was also patented around the same time by Scott Crump. FDM, also called Fused Filament Fabrication, differs from SLS and SLA in that rather than using light, the filament is directly extruded from a heated nozzle. FFF technology has gone on to become the most common form of 3D printing we see today.

These three technologies are not the only types of 3D printing methods that exist. But, they are the three that serve as the building blocks that would lay the groundwork for the technology to grow and for the industry to be disrupted.

In the 90s, many companies and startups began popping up and experimenting with the different additive manufacturing technologies. In 2006, the first commercially available SLS printer was released, changing the game in terms of creating on-demand manufacturing of industrial parts.

CAD tools also became more available at this time, allowing people to develop 3D models on their computers. This is one of the most important tools in the early stages of creating a 3D print.

During this time, the machines were very different from those that we use now. They were difficult to use, expensive, and many of the final prints required a lot of post-processing. But innovations were happening every day and discoveries, methods, and practices were being refined and invented.

Then, in 2005, Open Source changed the game for 3D printing, giving people more access to this technology. Dr. Adrian Bowyer created the RepRap Project, which was an open-source initiative to create a 3D printer that could build another 3D printer, along with other 3D printed objects.

In 2008, the first prosthetic leg was printed, propelling 3D printing into the spotlight and introducing the term to millions across the globe.

Then, in 2009, the FDM patents filed in the 80s fell into the public domain, altering the history of 3D printing and opening the door for innovation. Because the technology was now more available to new companies and competition, the prices of 3D printers began to decrease and 3D printing became more and more accessible.

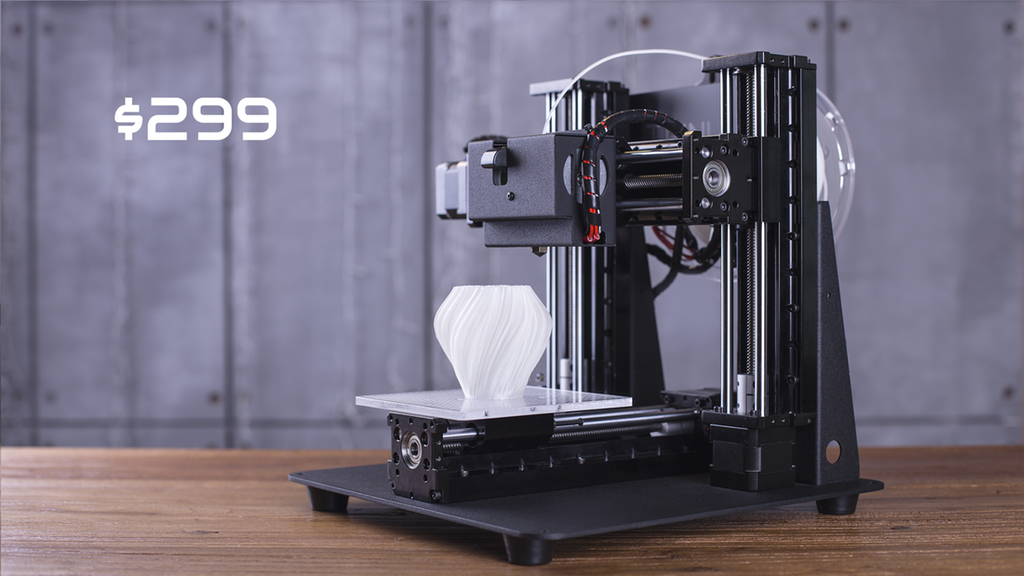

3D Printing NowIn the 2010s, the prices of 3D printers started to decline, making them available to the general public. Along with the lowering prices, the quality and ease of printing also increased.

The materials that printers use have also evolved. Now there are a variety of plastics and filaments that are widely available. Materials like Carbon Fiber and Glass Fiber can also be 3D printed. Some creatives are even experimenting with printing materials like chocolate or pasta!

Some creatives are even experimenting with printing materials like chocolate or pasta!

In 2019, the world’s largest functional 3D printed building was completed. 3D printing is now consistently used in developing hearing aids and other healthcare applications, and many industries and sectors have adopted the technology into their everyday workflow.

It’s safe to say that the history of 3D printing is still being written.

Innovations and ideas are created every day. We’re very excited to see what’s next!

It's Older Than You Think [Updated]

Published Date

Author Drew Turney- 3D printing has existed in concept since 1945 and in practice—however primitive—since 1971, proposing a faster and more efficient method of making things.

- Concurrent development of 3D-printing technology down to consumer use and up to enterprise use has realized the benefits of 3D printing in construction, architecture, design, manufacturing, and other industries.

- Continuing advancements in additive manufacturing technology and 3D-printable materials, especially new metal alloys, will contribute to further growth.

- In the future, look for new 3D-printing applications in the aerospace, electronics, medical, energy, and automotive industries.

What technology is 80 years old in theory, 40 years old in practice, and looks brand new? Believe it or not, it’s 3D printing.

Although the craze for desktop 3D printers began around 2010, when companies like MakerBot made investors and the media salivate, those in manufacturing know that the process—applying material onto a substrate to build up an object from a digital 3D design—goes back much further.

The first patent for a process called a Liquid Metal Recorder dates to the 1970s, but the idea is much older. In 1945, a prescient short story by Murray Leinster called “Things Pass By” describes the process of feeding “magnetronic plastics—the stuff they make houses and ships of nowadays—into this moving arm. It makes drawings in the air following drawings it scans with photo-cells. But plastic comes out of the end of the drawing arm and hardens as it comes.” What in Leinster’s day was science fiction soon became a reality.

Layers of Innovation: A 3D-Printing Timeline

1971–1999: The First 3D Printer Emerges

Inkjet technology was invented by the Teletype Corporation in the 1960s, a method of “pulling” a drop of material from a nozzle using electronics. It resulted in a device capable of printing up to 120 characters per second and ultimately paved the way for consumer desktop printing.

Teletype later experimented with melted wax as described in a 1971 patent belonging to Johannes F. Gottwald, whose idea was to output an object made of liquified metal that solidified into a shape predetermined by the inkjet’s movement upon each new layer. This device was the Liquid Metal Recorder, which is the basis of rapid prototyping and posited that “printing” could move beyond ink.

Gottwald, whose idea was to output an object made of liquified metal that solidified into a shape predetermined by the inkjet’s movement upon each new layer. This device was the Liquid Metal Recorder, which is the basis of rapid prototyping and posited that “printing” could move beyond ink.

Those were the baby steps into a territory called the material extrusion process, where thermoplastic is fed into a heated nozzle and laid upon an object one “slice” at a time in sequence—the same technique used in consumer desktop 3D printers. It’s speedy and cheap, but the materials (essentially rubbery plastic) aren’t good for much beyond model R2-D2s and racing cars.

Plans to print objects using liquified metal date to the 1970s, but practical metal additive manufacturing is much more recent—and will impact many more industries as new 3D-printable alloys become available.In 1980, Dr. Hideo Kodama, a lawyer working for a public research institute in the city of Nagoya, Japan, described two methods for Gottwald’s vision using thermoset polymer—a special plastic that hardens in response to light—instead of metal. His research was published in several papers and resulted in his own November 1981 patent, but a complete lack of interest meant the project went nowhere.

His research was published in several papers and resulted in his own November 1981 patent, but a complete lack of interest meant the project went nowhere.

Regardless, the seed was sown. Electronics and defense manufacturer Raytheon filed a patent in 1982 to use powdered metal to add layers to an object. In 1984, entrepreneur Bill Masters filed a patent for a process called Computer Automated Manufacturing Process and System, which mentioned the term 3D printing for the first time. Another 1984 patent in France described additive manufacturing using stereolithography, but like Kodama’s work, it was disregarded as having no commercial appeal.

3D Systems Corporation’s SLA-1After all these starts, inventor Chuck Hull was the first person to actually build a 3D printer. Based on his patent for curing photopolymers using radiation, particles, a chemical reaction, or lasers, his design sent the spatial data from a digital file to the extruder of a 3D printer to build up the object one layer at a time.

Hull’s company, 3D Systems Corporation, released the world’s first stereolithographic apparatus (SLA) machine, the SLA-1, in 1987. This machine made it possible to fabricate complex parts, layer by layer, in a fraction of the time it would normally take. Hull went on to file more than 60 patents around the technology, becoming the godfather of the rapid prototyping movement and inventing the STL file format that’s still in use today.

During this era, 3D printing was an emerging technology, and materials science wasn’t what it is today. If the product was made of popular polymers, they tended to warp as it set. At the time, the machines also cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, so 3D printing devices were installed only in heavy manufacturing plants—far out of the reach of consumers.

1999–2010: 3D Printing Shows Its PotentialAmid widespread worries that the Y2K bug would shut down computer systems and cause digital Armageddon, 3D printing showed great potential for many industries.

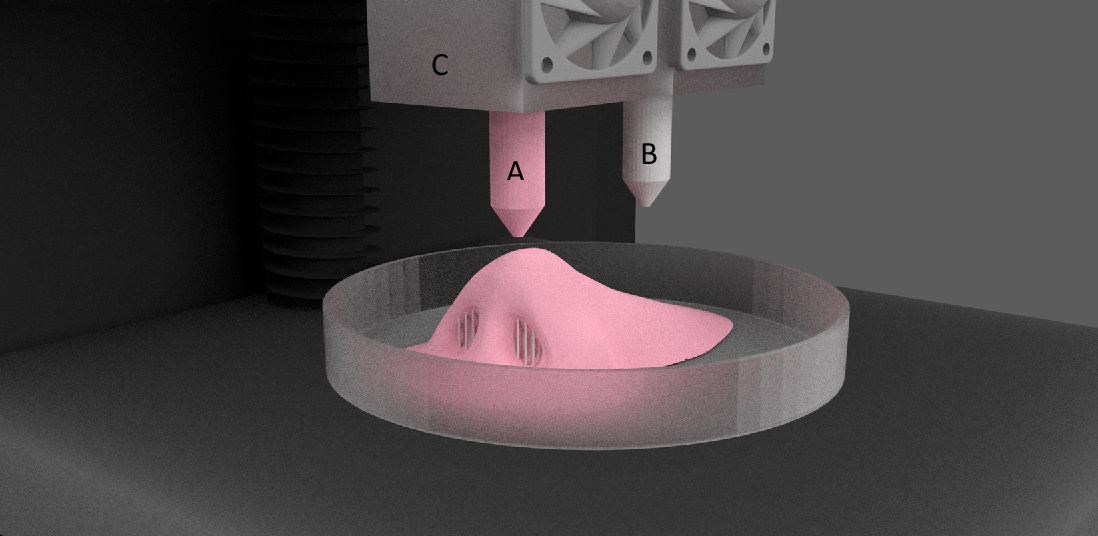

During this period, bioengineering was also making important advances. Scientists at Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC, printed the building blocks of a human urinary bladder using additive manufacturing and coating the organ with cells from the patient so the body was unlikely to reject the 3D-printed bladder.

The next decade saw many advances in medical 3D printing as scientists, technologists and doctors built a miniature kidney, a complex prosthetic leg, and the first bioengineered blood vessels made using donated human cells.

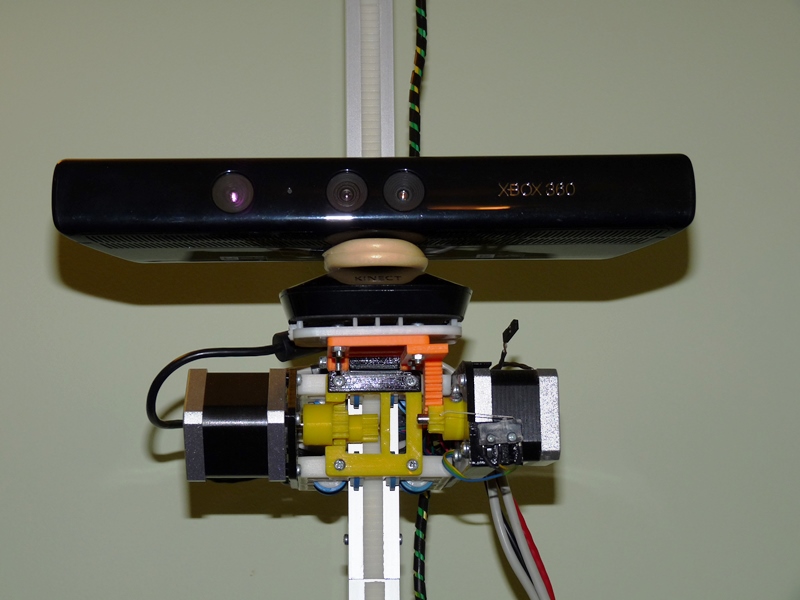

The 2005 open-source RepRap project produced the Darwin machine, a 3D printer that could print most of its own parts in order to self-replicate. Courtesy of RepRap.org.RepRap 3D PrinterBut the entire movement—especially the drive toward consumer use—received a big boost from the open-source paradigm sweeping the information and communications technology (ICT) sector. In 2005, Adrian Bowyer’s RepRap Project launched an open-source initiative to create a 3D printer that could build itself—or at least print most of its own parts.

The 1.0 Darwin machine was the first practical application of RepRap’s philosophy, and suddenly anyone had the power to create whatever they could dream up. Launched around the same time, Kickstarter gave home 3D printing another huge boost as crowdfunded projects sprung up everywhere. Manufacturing was democratizing fast.

MakerBot 3D PrinterCommercial 3D printing finally came to the desktop in 2006 from Objet (now Stratasys), which let users send designs to its device in order to print them from multiple materials with different properties.

Marketplaces and virtual swap meets for trading, sharing, and acquiring designs sprung up everywhere, driving a huge groundswell of interest. When MakerBot arrived in 2009 with open-source DIY kits to design and print just about anything, it made co-founder Bre Pettis into a superstar and gave 3D printing the same cachet as past emerging technologies like social media, e-commerce, and even the Web itself.

Today, additive manufacturing is a mature technology. The consumer interest and robustness of industrial platforms grew throughout the 2010s, as the (often hysterical) MakerBot hype settled down and the industry found a groove. Some think additive will replace traditional CNC and milling manufacturing in the future, and a 2021 Lux Research report predicts that 3D printing will be worth $51 billion by 2030.

The plastic desk toys have been cleared away, leaving the real-world benefits 3D printing offers: everything from printing food to applying multiple materials in the same extrusion process, making the process faster and cheaper.

The range of materials available for 3D printing has also grown exponentially, from bioprinting human tissue and the beginnings of organs tailor-made to patients to crafting products from silver or gold.

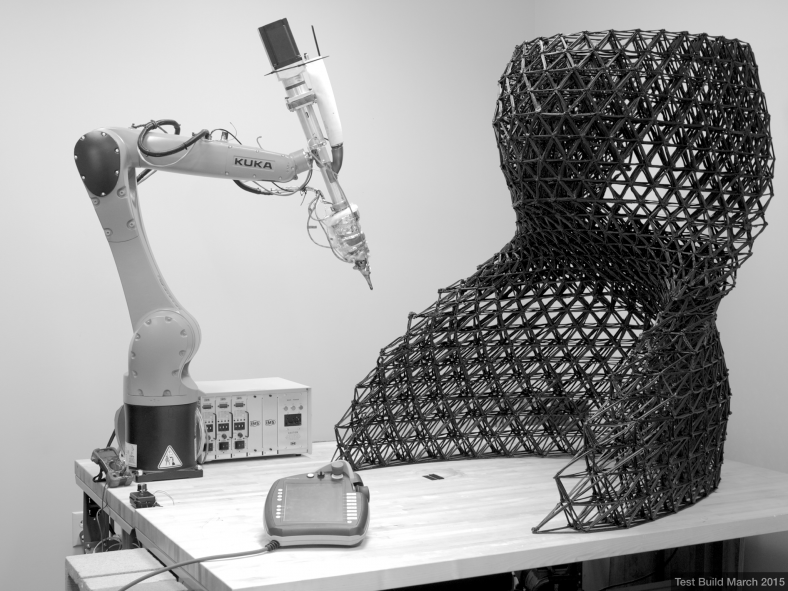

The applications are also as varied as inventors’ and engineers’ imaginations. Scientists at the University of Southampton flew the world’s first 3D-printed unmanned aircraft; the makers of a 3D-printed car reached up to 200 mpg with a hybrid gas/electric engine; and a start-up specializing in building ecological living structures came up with a robot-made habitat suitable for living on Mars.

3D printing is being used to build emergency shelter in disaster areas and affordable housing in the developing world. And smart robotics, micromanufacturing, and articulated limb design were combined to to make self-powered prosthetics that give feedback to the brain.

A lot of high-end 3D printing in manufacturing for large structures is done using powder-bed fusion, where various materials can be used in powdered form and fused together using lasers or heat. This is the main process used for metal parts, but it’s expensive and needs very particular infrastructure, making it mainly been feasible for the heavy manufacturing sector.

Nevertheless, additive manufacturing has found a home in many industries. The amount of things from your daily life with some 3D-printed component may surprise you.

3D Printing in ConstructionConstruction is a massive, entrenched field with a legacy of wasteful and dangerous practices, responsible for almost 40% of greenhouse gas emissions. 3D printing could upend it with cleaner methods of creating cement-based products like walls and metal components like rebar—and climate change makes these changes even more crucial.

But speed is another compelling reason to adopt 3D printing. In 2016, a Chinese company 3D printed an entire two-story house in 45 days. That same year, Apis Cor 3D printed the structure of a 400-square-foot house in only 24 hours. Additive technologies can also be deployed in precarious places like mine sites or disaster areas quickly and cheaply; research is ongoing to use materials found onsite where printers are located instead of using more fuel and smoke-belching trucks to ship in materials.

The biggest benefits of 3D printing to architecture seem obvious: designs already exist with every conceivable detail in digital form, so when you want to impress clients or investors, simply click a button and have a gorgeous model on your boardroom table just hours later. Want to change a beam, reorient a window, or add another story? Redo your drawings, rinse, and repeat.

3D Printing in Product Design and ManufacturingWhen prototypes have to be made in or near the same factories where final production kicks into gear, it adds precious time to the design and review phase of product development if the designer and manufacturer are located far apart.

With access to 3D printing, it doesn’t matter how far-flung the factory is; a 3D printer in your office or garage can churn out as many prototypes as you need affordably and quickly, no matter how many design tweaks you have to make.

3D printing has the potential to make manufacturing viable in any region or economic climate, rather than only in the manufacturing hubs of the past 30–40 years.

A lot of manufacturing workflows already have the means to retool to additive processes. And as the product-design timeline is compressed further thanks to advances such as generative design and the easier transport and repurposing of design files, prototyping and production will happen faster, all at the speed of digital.

Early consumer 3D printing also promised to help reduce waste through a little less built-in obsolescence. If the broken part in an old vacuum cleaner isn’t in production anymore, but the design file for it still exists on the manufacturer’s website, you only have to send it to your desktop device and watch a quick YouTube video to learn how to install it.

What Is the Future of 3D Printing?According to Statista, the global additive manufacturing market is expected to grow 17% annually through 2023, as the applications for the technology increases and metal additive becomes more and more viable. And the market for additive manufacturing products and services is expected to almost triple between 2020 and 2026.

And the market for additive manufacturing products and services is expected to almost triple between 2020 and 2026.

Industries such as manufacturing, architecture, and product design are surely reaping the benefits of 3D printing, but some of the greatest growth is expected in the electronics, aerospace, and medical industries. Todd Spurgeon, additive manufacturing project engineer for America Makes, says the electronics industry will see things like custom heat sinks for high-end products, and the aerospace industry will see a larger availability of 3D-printed components that will make their way from higher-end military applications to general aviation. In the medical industry, as more materials are evaluated for medical applications and insurance companies more broadly recognize additive manufacturing, personalized care will become the norm.

“Gone may be the days of the one-size-fits-most expensive prosthetic,” Spurgeon says. “Soon, personalized prosthetics, custom-fit to the user, are expected to be within the reach of the typical American household—even for growing children.”

New Applications and New 3D-Printable MaterialsBeyond the existing technologies, there is much more on the horizon for additive manufacturing. According to Spurgeon, interesting work is being done in the direct-ink-writing and dense paste material extrusion communities. For example, research groups are exploring mixing cured photopolymers with advanced material systems such as ceramics and thermosets, which can ultimately be used for things like printed circuits, lower-cost heat exchangers, and nonbulk ceramics.

“Improvements in this domain could result in a larger insertion of additive manufacturing into high-end applications such as aerospace and automotive, as well as large production processes such as the desalinization of water,” Spurgeon says. Even more opportunities surface when you consider this technology in conjunction with other additive-manufacturing modalities, such as printed circuits integrated into the structure of prosthetics or new form factors for batteries.

Even more opportunities surface when you consider this technology in conjunction with other additive-manufacturing modalities, such as printed circuits integrated into the structure of prosthetics or new form factors for batteries.

The list of 3D-printable materials is growing, as well. “Refractory super alloys will enable innovations in the energy, aerospace, and defence sectors,” Spurgeon says. “More durable polymers are being developed today that are likely to meet flame, smoke, and toxicity testing required by the FAA, which will result in sustainment costs reduction for relevant sectors.”

With new research and developments in additive manufacturing on the rise, the future remains bright for 3D printing—so bright that it’s time to don your new 3D-printed shades.

This article has been updated. It was originally published in September 2014. Dana Goldberg contributed to this article.

About the Author

After growing up knowing he wanted to change the world, Drew Turney realized it was easier to write about other people changing it instead. He writes about technology, cinema, science, books, and more.

He writes about technology, cinema, science, books, and more.

Content by Drew Turney

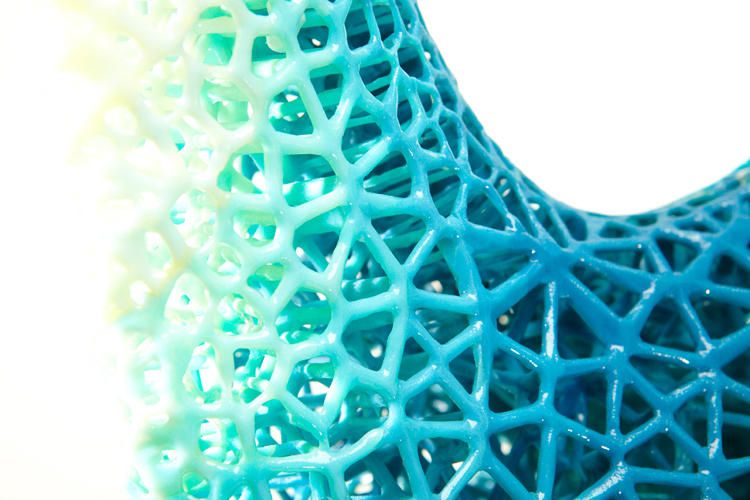

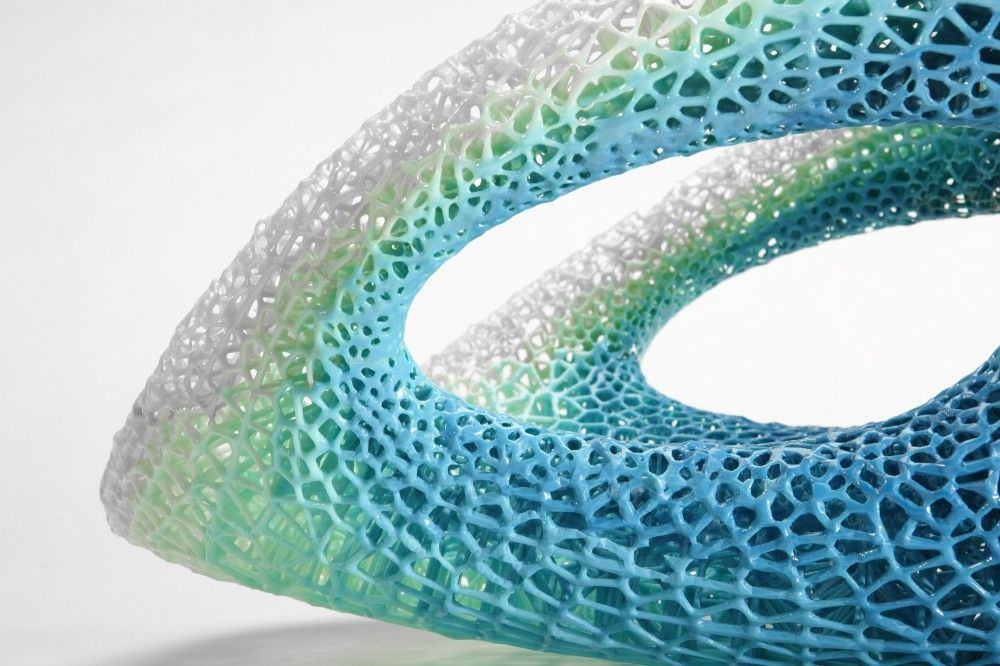

Dita Von Teese 3D Printed Dress

Designer Michael Schmidt and architect Francis Bitonti of New York created a dress for burlesque dancer Dita Von Teese using 3D printing.

Designed by Michael Schmidt and designed by Francis Bitonti, this floor length nylon gown was made using selective laser sintering (SLS), where the material was formed in layers of plastic powder fused together by a laser.

All of the hard plastic components of the dress have a mesh structure and are connected in a way that does not impede movement. The baselines and spirals were based on the Golden Ratio and applied to Dita Von Teese's computer rendered body, so the dress fits her perfectly.

Under the dress there is a skin-colored silk corset, and the black patent leather dress with puffy sleeves and a narrow waist is decorated with 12,000 Swarovski crystals. The dress was unveiled at the Ace Hotel in New York in early March 2013 as part of a line of products featured on the Shapeways 3D technology marketplace, which printed the dress and 3D bikini a few years earlier.

The dress was unveiled at the Ace Hotel in New York in early March 2013 as part of a line of products featured on the Shapeways 3D technology marketplace, which printed the dress and 3D bikini a few years earlier.

Among other 3D printed fashion events, we can highlight Iris van Herpen's fashion show at Paris Fashion Week. Recently, 3D printing has also been used to design cars and create studs for American football boots.

Learn more from Michael Schmidt:

For the first time anywhere, fashionable clothing that has been designed and created using a revolutionary 3D printed powder nylon process can move like textiles.

On Monday night, March 4, 2013, style icon Dita Von Teese appeared at the Ace Hotel in New York City as a futuristic vision of a femme fatale in fully realized and computer generated clothing that moves with all sensuality and fluidity. its owner. When creating the dress, designer Michael Schmidt and his technologists at Shapeways did not use a pen, paper or needle.

This revolutionary, computer-printed, flexible "fabric" is the result of countless hours of work between Mr. Schmidt and an outstanding architect, Francis Bitoni. "Francis was able to take my sketches for the dress I created specifically for Dita and translate them into programming language," says Mr. Schmidt. heated chamber based on information from the CAD file. The laser "sinters" the nylon into a specific shape, a process known as laser sintering or "SLS". The articulations of the tissue are built by themselves using 3D. This is something that no one has ever done before. What Francis and Shapeways have achieved here is truly amazing.”

The mobility created in sintered nylon is what sets this design apart from the innovative work of other modelers who are exploring 3D printing. Mr. Schmidt was able to realize and convey the fluidity in powdered nylon construction that has long been a hallmark of modeling architects and industrial designers.

The vision of science meets the beauty of classicism in this historic dress. “It all comes down to mathematics,” Mr. Schmidt notes, “beauty is realized through mathematics.” Its basis was the theory of the Golden Mean by the 13th century theorist Fibonacci, whose beauty formula is still used by artists and scientists. The theory is based on the fact that in nature there is a spiral, the laws of which absolutely everything obeys, from the human ear and a pine cone to the whole galaxy.

“It all comes down to mathematics,” Mr. Schmidt notes, “beauty is realized through mathematics.” Its basis was the theory of the Golden Mean by the 13th century theorist Fibonacci, whose beauty formula is still used by artists and scientists. The theory is based on the fact that in nature there is a spiral, the laws of which absolutely everything obeys, from the human ear and a pine cone to the whole galaxy.

Mr. Schmidt, together with Mr. Bitoni, applied the spiral formula to the computer rendering of the dress, which was supposed to wrap around the body in the most feminine way in spirals in a grid pattern. For this reason, Mr. Schmidt turned to his longtime friend and muse, Dita Von Teese, whom he considers the perfect epitome of classical beauty. The entire structure was built around a flesh-colored silk corset, and much of the silhouette's architecture, from the voluminous shoulders to the tapered waist, is solid powdered nylon. The long, floor-length skirt moves and expands with Ms. Von Teese's body movements thanks to its mesh structure.

Von Teese's body movements thanks to its mesh structure.

17 sections were printed with a printer and then hand-assembled into a dress. (Most of Mr. Schmidt's work over the years has involved this time-consuming process.) The 3D printed dress was then meticulously polished and finished with black lacquer, and hand embellished with 12,000 Swarovski crystals to give the overall impression and effect of uber glamour.

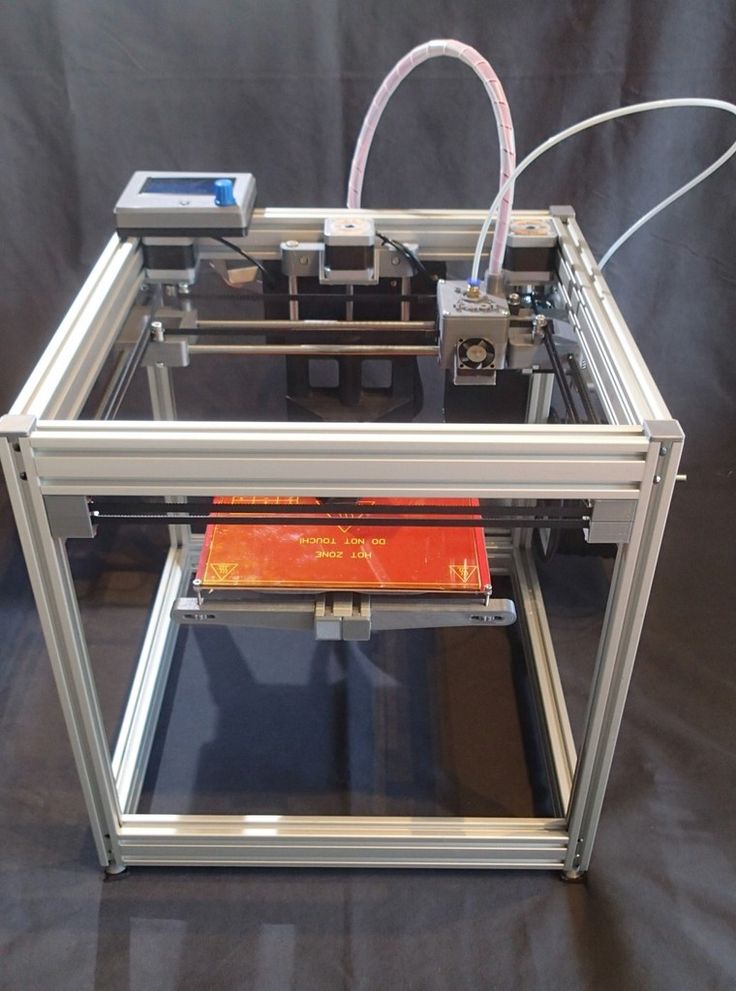

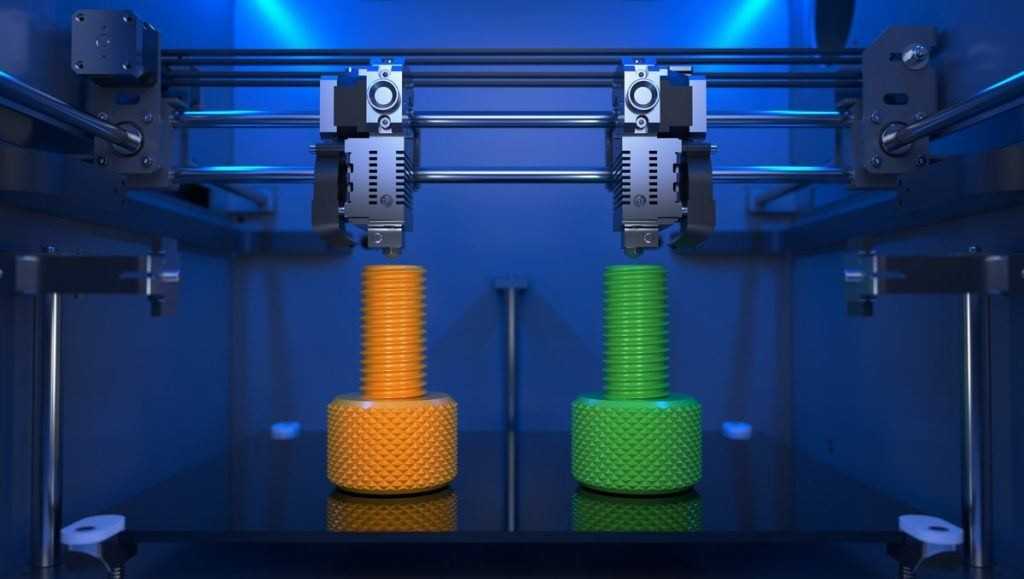

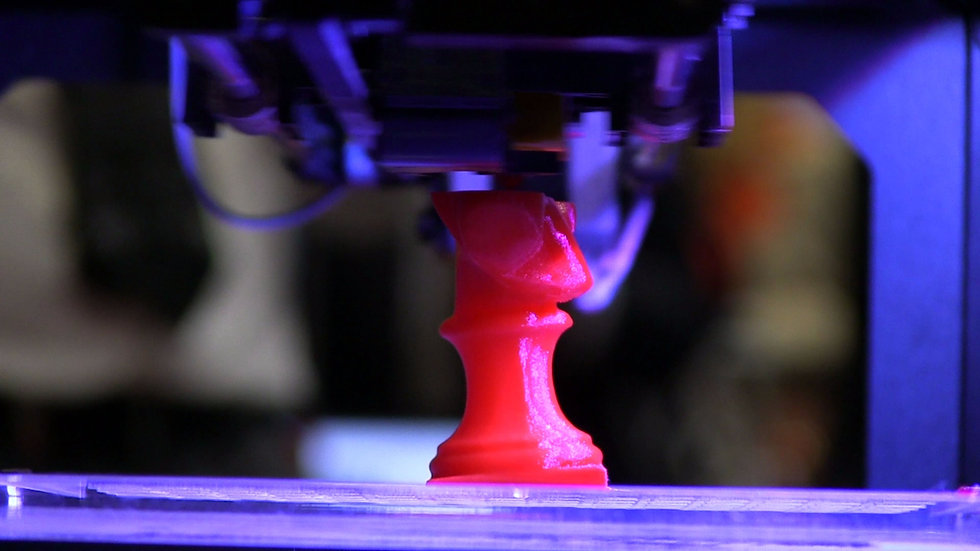

Printing a 3D box with a 3D printer. Blue background . stock photo ©3dmentat 88914716

Printing a 3D box with a 3D printer. Blue background . Stock Photo ©3dmentat 88914716Enter the account to see the special offers of December

Images

Video -based music and sounds

Tools

for business

Our prices

All images

Login this image,

ACCAUnt already? Log in

I accept the terms of the User Agreement Receive news and special offers

3D object process from 3D electronic printer .

— Photo by 3dmentat

Similar licensed images:

Show moreShow more

Same series:

Process of a 3D object made in an electronic 3D printer and packaging. 688 _ 001a Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), a sign of zodiacal astrology with a warm color of the luminous surface .3D object process from electronic 3D printer and packaging .Pile of hundreds of Chinese yuan banknotesPregnancy test in action. Question mark in result window .Growth business graph with financial profit Libra (libra), astrology horoscope zodiac sign with warm color glowing surface .Barrels with hazardous biological waste thrown under water .Stacks of chinese yuanClose up big red button during an emergency. Red emergency light flashes in the background .Image of shooting under water toredo .Suitcase with labels of world famous travel destinations at the airport New type Trip Switch Fuse box. All switches are in the "ON" position. Electricity, electricity, fuses .

View More

Similar Stock Video:

Simple Animation of 3D Printing .Printing a plant box with a 3D printer. Blue background .Simple animation of printing on a 3D printer .Simple animation of printing on a 3D printer .Simple animation of printing on a 3D printer .Simple animation of printing on a 3D printer .Old rusty bicycle carcass in a freshly plowed field on a cloudy day, time is running out 4K A simple 3D printer print animation .Startup process shows animation. Web technologies online application service internet business animated concept flat 3d isometric. Spaceship rocket taking off laptop keyboard 4k video .The luggage basket rotates on a white background. The solar swing swings, but no one is on it. 4K Abandoned empty swings swinging in the wind at the outdoor playground - in the park autumn sunny day, Close up swings in autumn Outdoor swings in motion without anyone on them. 4K Empty hanging swing in the open yard, sad childhood memories, creepy horrorShow more

Usage information

You can use this royalty-free photo "Printing a 3D box with a 3D printer.