3D printing and medical devices

3D Printing of Medical Devices

Coronavirus COVID-19 Information Related to 3D Printing of Medical Devices

- FAQs on 3D Printing of Medical Devices, Accessories, Components, and Parts during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Overview

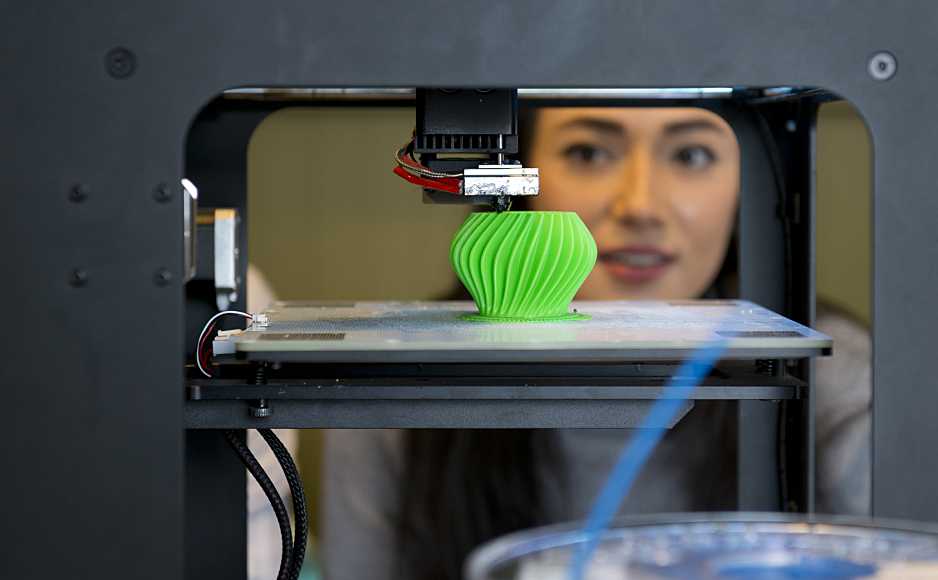

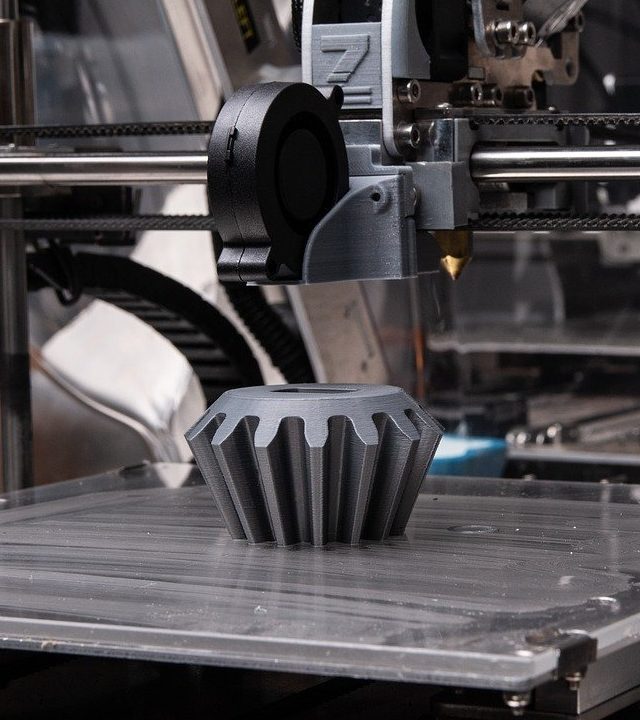

3D printing is a type of additive manufacturing. There are several types of additive manufacturing, but the terms 3D printing and additive manufacturing are often used interchangeably. Here we will refer to both as 3D printing for simplicity.

3D printing is a process that creates a three-dimensional object by building successive layers of raw material. Each new layer is attached to the previous one until the object is complete. Objects are produced from a digital 3D file, such as a computer-aided design (CAD) drawing or a Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI).

The flexibility of 3D printing allows designers to make changes easily without the need to set up additional equipment or tools. It also enables manufacturers to create devices matched to a patient’s anatomy (patient-specific devices) or devices with very complex internal structures. These capabilities have sparked huge interest in 3D printing of medical devices and other products, including food, household items, and automotive parts.

3D printed (left to right, top) models of a brain, blood vessel, surgical guide, and (bottom) medallion printed on FDA 3D printers.

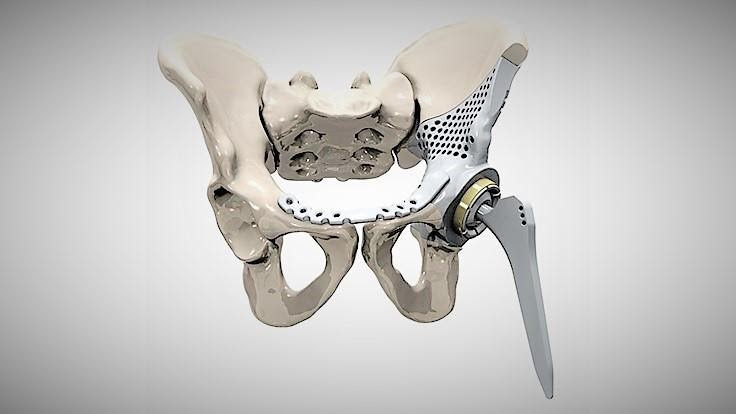

Medical devices produced by 3D printing include orthopedic and cranial implants, surgical instruments, dental restorations such as crowns, and external prosthetics.

Due to its versatility, 3D printing has medical applications in:

- Medical devices regulated by FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH),

- Biologics regulated by FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and

- Drugs regulated by FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

Medical device manufacturers should refer to FDA guidance documents and Quality Systems regulations for more information on specific applications.

Additional Resources

- The 3Rs of 3D Printing: FDA's Role Learn how the FDA reviews and researches 3D printed medical products to protect the public health.

- Technical Considerations for Additive Manufactured Medical Devices - Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff (PDF - 803KB) FDA’s thinking on technical considerations specific to devices using additive manufacturing, the broad category of manufacturing encompassing 3D printing.

- How 3D Printers Work

A resource from the Department of Energy and includes descriptions of different types of printing processes - NIH 3D Print Exchange

Offers a unique set of models, learning resources and tutorials to create and share 3D-printable models related to biomedical science. The goal of the project is to facilitate the application of 3D printing in the biosciences. - American Society of the International Association for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International Committee F42 on Additive Manufacturing Technologies

This is a collaborative, consensus organization that has published standards and test methods for additive manufacturing and 3D printing.

- America Make

A public private partnership whose members, including the FDA, are working together to innovate and accelerate 3D printing to increase our nation’s global manufacturing competitiveness.

Guide to 3D Printing Medical Devices

3D printing has been driving innovative solutions and impacting the development of medical devices for decades from R&D through to production. As 3D printers have become more affordable and investments in machines and materials accelerate, more companies are gaining access to 3D printing to disrupt the status quo of the healthcare industry.

By bringing 3D printing in-house, medical device developers and manufacturers can reduce both cost and time to market. The technology enables more nimble product development, novel final-use parts, and the creation of personalized medical devices that would be impossible to produce using traditional tools. As demonstrated since early 2020, additive manufacturing also enables unprecedented speed from concept to mass production of emergency medical supplies.

As demonstrated since early 2020, additive manufacturing also enables unprecedented speed from concept to mass production of emergency medical supplies.

In this comprehensive guide, we look at the different applications of 3D printing for medical devices, compare the most common 3D printing processes for the medical industry, and provide a brief overview (and links to more resources) about the regulatory process for 3D printed medical devices.

Webinar

Join Formlabs for this introduction to learn best practices for medical 3D printing and see the latest Formlabs Medical ecosystem, including multiple new medical-grade products!

Watch the Webinar Now

The combination of speed, affordability, customizability, and design freedom that 3D printing offers has led to a wide range of use cases in the medical device industry. Let’s look at the most common applications and real-world examples that highlight the versatility of 3D printing.:quality(80)/images.vogel.de/vogelonline/bdb/1612700/1612740/original.jpg)

Developing innovative products goes hand in hand with advancing patient care and improving outcomes within the healthcare industry. Prototyping is a key element of this iterative process in which revisions are made, implemented, and tested in a controlled environment.

Rapid prototyping is the group of techniques used to quickly fabricate a full scale model of a physical part or assembly using three-dimensional computer-aided design (CAD) data. 3D printing is a natural match for prototyping: it provides almost unlimited form freedom, doesn’t require tooling, and can produce parts with mechanical properties that closely match those produced with traditional manufacturing methods.

“Previously, we relied almost exclusively on outside print vendors for prototypes. Today, we are running four Formlabs machines, and the impact has been profound. Our rate of 3D printing has doubled, cost has been reduced by 70 percent, and the level of print detail allows for clear communication of designs with orthopedic surgeons.

”

Alex Drew, Mechanical Project Engineer, DJO Surgical

3D printing provides manufacturers with the flexibility to develop looks-like, feels-like, and works-like prototypes of even the most complex medical devices. New iterations can be completed within hours and validated to determine if further changes are required. Applying 3D printing also enables the development of medical device prototypes using diverse materials in scenarios in which properties like strength, flexibility, or heat resistance are important criteria for the functioning of the device.

Testing a functional prototype using real-world validation processes provides the manufacturer with results to base further iterations. 3D printed prototypes can also serve as presentation pieces when pitching investors or engaging with future customers.

The ease of use and low cost of in-house 3D printing has also revolutionized product development. Over 85 percent of the 50 largest medical device manufacturers have adopted Formlabs technology to produce prototypes, manufacturing aids, or end-use devices. Due to a CAPEX starting under $5,000, many startups and small businesses have also benefited from the technology.

Due to a CAPEX starting under $5,000, many startups and small businesses have also benefited from the technology.

For example, UK-based medical device design company Coalesce Product Development develops drug delivery devices, including inhalers and injectors. The manufacturer struggled with developing complex medical device prototypes using traditional manufacturing processes due to the high start-up costs and time-consuming operations associated with traditional production tools.

The company turned to in-house desktop stereolithography (SLA) 3D printers to prototype, test, and create various devices in a multitude of different shapes and sizes. With 3D printing, they created new prototypes in under 24 hours at 10-20x lower cost compared to outsourcing. Beyond 3D printing the prototypes, they also 3D print test fixtures and jigs to accelerate the testing of their inhalers.

Medical device design company Coalesce uses 3D printing to prototype drug delivery devices, such as inhalers.

Webinar

In this webinar, Gaurav Manchanda, Director of Medical Market Development at Formlabs, hosts current Formlabs customers in the medical industry. Companies range from startups to larger firms with $1B+ in sales, including Cortex Design, DJO Surgical, Psyonic, and TensionSquare.

Watch the Webinar Now

Most traditional manufacturing processes such as injection molding or thermoforming require expensive tooling, which means they are not efficient for producing customized or personalized parts. 3D helps address this challenge in two ways.

First, 3D printing can be used to manufacture custom rapid tooling such as 3D printed molds, patterns, casts, and dies for a range of traditional manufacturing processes, including injection molding, thermoforming, silicone molding, overmolding, insert molding, compression molding, metal casting, and more.

One vacuum forming example is dental aligners and retainers that are designed and created based on unique patient anatomy collected through intraoral or desktop scanning devices. Manufacturing these devices involves vacuum forming a plastic sheet over a custom model for each step of the treatment. As 3D printers can produce these models directly from the digital files within a few hours, they’ve become the go-to method for producing these increasingly popular devices in orthodontics.

Manufacturing these devices involves vacuum forming a plastic sheet over a custom model for each step of the treatment. As 3D printers can produce these models directly from the digital files within a few hours, they’ve become the go-to method for producing these increasingly popular devices in orthodontics.

3D printing is the go-to method for manufacturing models for vacuum forming clear aligners and retainers.

Another example comes from Cosm, a medical device company developing a supportive treatment for patients suffering from pelvic floor disorders. The company uses 3D printed molds for silicone molding to create a tailored treatment for each patient’s specific case.

Utilizing 3D printing gives Cosm the flexibility and affordability it requires to manufacture custom pessary molds within 24 hours.

Cosm manufactures custom pessaries using silicone molding.

White Paper

Download our white paper to learn about six moldmaking processes that are possible with an in-house SLA 3D printer, including injection molding, vacuum forming, silicone molding, and more.

Download the White Paper

Second, 3D printing is also increasingly used to manufacture final-use, patient-specific medical devices. As 3D printing processes don’t require tooling, they make it possible to create custom parts and complex designs in a streamlined, cost-efficient manner.

Once again, dentistry is one of the fields leading the adoption of 3D printing in medicine. Surgical guides, splints, temporary and permanent restorations, and dentures can all be directly 3D printed.

Permanent crowns manufactured using a ceramic-filled resin material.

Other end-use 3D printed medical device applications include custom-fit ear devices such as hearing aids and noise protection equipment as well as strong and durable custom prosthetics, orthotics, and more.

3D printing can be used to create durable and biocompatible patient-specific prosthetics and orthotics at an affordable price and faster than ever before.

Surgical instruments manufacturer restor3d leverages 3D printing capabilities to drastically improve surgical care delivery by 3D printing procedure-specific instruments for cervical spine implants. Using 3D printing empowers them to create sterile, surgeon-designed tools using a truly agile development process. The restor3d approach leads to reduced sterilization, warehousing, and OR costs for hospitals and surgical centers and demand has been strong: over 25 Formlabs machines are manufacturing devices around the clock.

Using 3D printing empowers them to create sterile, surgeon-designed tools using a truly agile development process. The restor3d approach leads to reduced sterilization, warehousing, and OR costs for hospitals and surgical centers and demand has been strong: over 25 Formlabs machines are manufacturing devices around the clock.

restor3d uses 3D printing to manufacture procedure-specific surgical instruments.

White Paper: Medical Case Studies

In this report, learn how Formlabs Medical helps medical device firms bring digital fabrication in-house, and get inspired through the examples of four companies currently creating groundbreaking devices using 3D printing.

Download the White Paper

Beyond surgical tools, 3D printing is also increasingly popular for producing medical devices or components of medical devices, especially for complex designs that would be inefficient or impossible to manufacture with traditional processes.

Tension Square has commercialized a device that holds a needle decompression secure in place while preventing kinking, folding, or dislodgement that often lead to preventable fatalities in the field. After years of R&D, the company is now 3D printing the final end-use device on a Fuse 1 selective laser sintering (SLS) 3D printer, that allows them to reduce the reliance on outsourced providers and produce 100+ devices per printer within 24 hours. The company, founded by a veteran and paramedic, intends to produce millions of parts per year using 3D printing at its US-based manufacturing facilities.

Tension Square 3D prints a PTX decompression catheter stabilization device directly using SLS 3D printing.

VO2 Master develops a portable metabolic analyzer that is easier to use and more affordable than established machines. After using 3D printing extensively in the prototyping process, the company also decided to 3D print the end-use outside shells of the device to be able to get to market faster. The shells are printed on SLA 3D printers in Tough 1500 Resin, a resilient material that simulates the strength and stiffness of polypropylene. The printed parts are painted white before being fastened to the mask, to improve surface finish, emboss coloration, and durability.

The shells are printed on SLA 3D printers in Tough 1500 Resin, a resilient material that simulates the strength and stiffness of polypropylene. The printed parts are painted white before being fastened to the mask, to improve surface finish, emboss coloration, and durability.

VO2 Master 3D prints the outer shell for their portable metabolic analyzer, allowing them to get to market faster.

The COVID-19 pandemic overwhelmed healthcare centers and medical supplies in unprecedented ways that left most governments scrambling for resources in unlikely places. To deal with the overwhelming need for supplies, automobile manufacturers pivoted to manufacturing respirators while fashion houses produced protective equipment to mitigate challenges associated with the pandemic.

As COVID-19 cases soared, the need for widespread testing increased, which led to a global shortage of the nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs needed to collect samples for COVID-19 testing. After identifying that nasal swabs for testing COVID-19 were in high demand and extremely limited supply, a team from USF Health, Northwell Health, and Formlabs collaborated to create a 3D printed alternative. Over the span of one week, the teams worked together to develop a nasal swab prototype and test it in the USF Health and Northwell Health labs. In two days, USF Health and Northwell Health developed prototypes using Formlabs’ 3D printers and biocompatible, autoclavable resins. Just 12 days after the initial idea, the final design was cleared for clinical use and the 3D file was made available for other health systems worldwide. Along with the file, the collaborators developed a detailed workflow with guidelines for qualified users in healthcare to print the swabs and ensure the health and safety of patients.

Over the span of one week, the teams worked together to develop a nasal swab prototype and test it in the USF Health and Northwell Health labs. In two days, USF Health and Northwell Health developed prototypes using Formlabs’ 3D printers and biocompatible, autoclavable resins. Just 12 days after the initial idea, the final design was cleared for clinical use and the 3D file was made available for other health systems worldwide. Along with the file, the collaborators developed a detailed workflow with guidelines for qualified users in healthcare to print the swabs and ensure the health and safety of patients.

3D printed swabs enabled over 70 million COVID tests in 25 countries in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hospitals, dental labs, and academic medical centers that had been using their 3D printers for patient-specific surgical devices were able to repurpose their equipment and fill a gap in their own supply chains by producing 3D printed swabs in-house. With the accessible design, affordable equipment, and validated processes, the swab design enabled over 70 million COVID tests in 25 countries.

Other solutions to meet the need for more ventilators included the conversion of bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machines that are normally used to relieve sleep apnea. Successful conversion requires the use of a BiPAP adapter that turns these machines into functional invasive mechanical ventilators.

To ensure enough BiPAP adapters were quickly created to provide patients with breathing support, Northwell Health, New York’s largest healthcare provider, designed 3D printable BiPAP adapters. The FDA granted Formlabs an Emergency Use Authorization to 3D print these adaptors to assist healthcare centers while traditional ventilators were unavailable.

When it comes to 3D printers for medical devices, not all methods are created equal. It is important to choose the right printing technology for specific use cases.

The most popular 3D printing technologies for medical devices include stereolithography (SLA), selective laser sintering (SLS), and fused deposition modeling (FDM) for plastic parts, and direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) and selective laser melting (SLM) for metals.

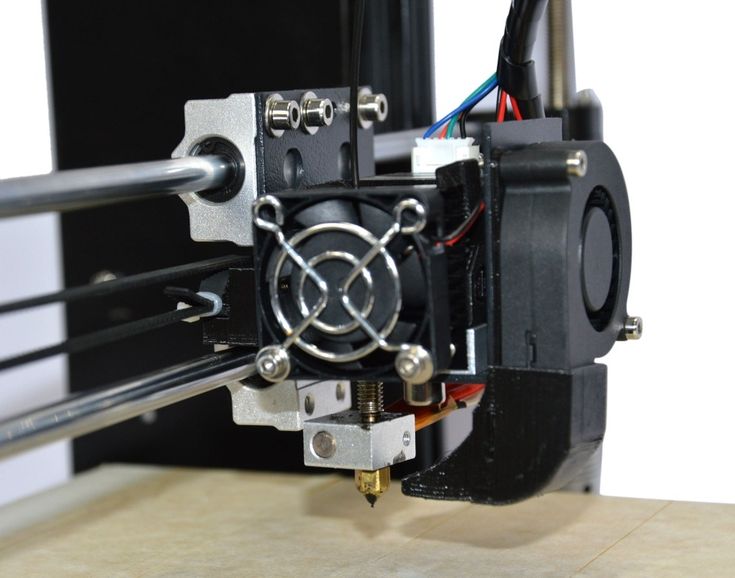

SLA 3D printers use a laser to cure liquid resin into hardened plastic in a process called photopolymerization. SLA is one of the most popular processes among medical professionals due to its high resolution, precision, and material versatility.

-

Advantages of SLA

SLA parts have the highest resolution and accuracy, the clearest details, and the smoothest surface finish of all plastic 3D printing technologies. The main benefit of SLA, however, lies in its versatility. SLA resin formulations offer a wide range of optical, mechanical, and thermal properties to match those of standard, engineering, and industrial thermoplastics.

SLA is a great option for highly detailed medical device prototypes requiring tight tolerances and smooth surfaces, as well as molds, tooling, patterns, medical models, and functional end-use parts. SLA also offers the widest selection of biocompatible materials for dental and medical applications. With Draft Resin, the Formlabs SLA printers are also the fastest options for 3D printing large prototypes, up to 10X faster than FDM.

SLA’s wide versatility comes with a slightly higher price tag than FDM, but it is still more affordable than all other 3D printing processes. SLA resin parts also require post-processing after printing, which includes washing the parts and post-curing.

SLA 3D printing offers a wide selection of 3D printing materials, including biocompatible materials, for a variety of medical and dental applications.

Sample part

See and feel Formlabs SLA quality firsthand. We’ll ship a free sample part to your office.

Request a Free Sample Part

SLS 3D printers use a high-powered laser to fuse small particles of polymer powder. The unfused powder supports the part during printing and eliminates the need for dedicated support structures, making SLS a particularly effective choice for complex mechanical parts.

Its ability to produce parts with excellent mechanical capabilities makes SLS the most common polymer additive manufacturing technology for industrial applications. Depending on the material, SLS nylon parts may also be biocompatible and sterilizable.

Depending on the material, SLS nylon parts may also be biocompatible and sterilizable.

-

Advantages of SLS

Since SLS printing doesn’t require dedicated support structures, it’s ideal for complex geometries, including interior features, undercuts, thin walls, and negative features. Parts produced with SLS printing have excellent mechanical characteristics, with strength resembling that of injection-molded parts.

The most common material for SLS is nylon, a popular engineering thermoplastic with excellent mechanical properties. Nylon is lightweight, strong, and flexible, as well as stable against impact, chemicals, heat, UV light, water, and dirt. 3D printed nylon parts can also be biocompatible and not sensitizing, which means that they are ready to wear and safe to use in many contexts.

The combination of low cost per part, high productivity, established materials, and biocompatibility makes SLS a popular choice among medical device developers for functional prototyping, and a cost-effective alternative to injection molding for limited-run or bridge manufacturing.

SLS 3D printers have a higher entry price than FDM or SLA technologies. While nylon is a versatile material, material selection for SLS is also more limited than for FDM and SLA. Parts come out of the printer with a slightly rough surface finish and require media blasting for a smooth finish.

SLS 3D printing is ideal for strong, functional prototypes and end-use parts, such as prosthetics and orthotics.

Sample part

See and feel Formlabs SLS quality firsthand. We’ll ship a free sample part to your office.

Request a Free Sample Part

FDM, also known as fused filament fabrication (FFF), is a printing method that builds parts by melting and extruding thermoplastic filament, which a printer nozzle deposits layer by layer in the build area.

FDM is the most widely used form of 3D printing at the consumer level, fueled by the emergence of hobbyist 3D printers. Industrial FDM printers are, however, also popular with professionals.

-

Advantages of FDM

FDM works with an array of standard thermoplastics, such as ABS, PLA, and their various blends. This results in a low price of entry and materials. FDM best suits basic proof-of-concept models and the low-cost prototyping of simpler parts. Some FDM materials are also biocompatible.

FDM has the lowest resolution and accuracy when compared to other 3D printing technologies for plastics such as SLA or SLS, which means that it is not the best option for printing complex designs or parts with intricate features. Higher-quality finishes require labor-intensive and lengthy chemical and mechanical polishing processes. Some industrial FDM 3D printers use soluble supports to mitigate some of these issues and offer a wider range of engineering thermoplastics, but they also come at a steep price. When creating large parts, FDM printing also tends to be slower than SLA or SLS.

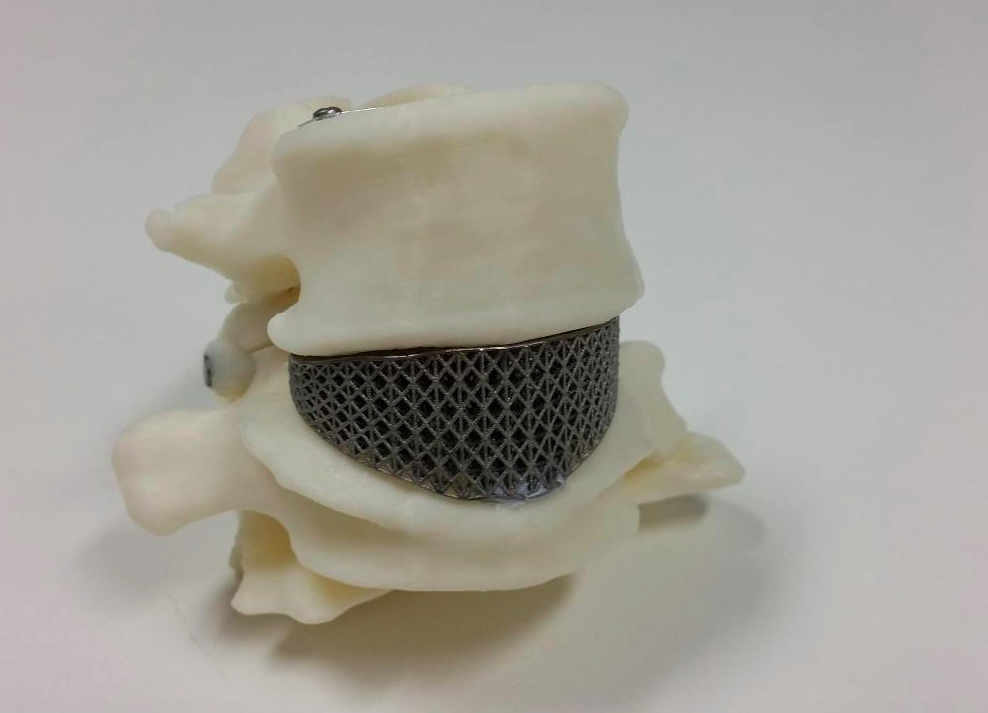

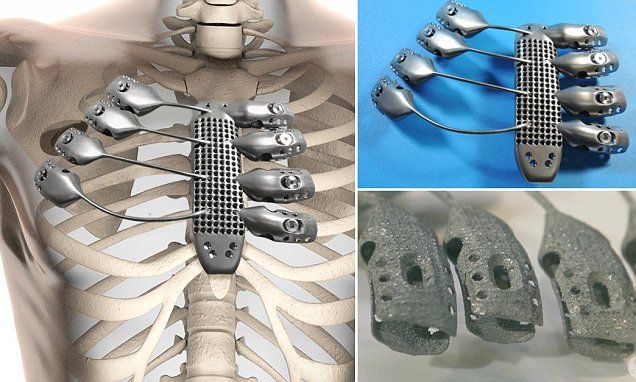

Direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) and selective laser melting (SLM) 3D printers work similarly to SLS printers, but fuse metal powder particles together layer by layer using a laser instead of polymers.

DMLS and SLM 3D printers can create strong, accurate, and complex metal products, making this process ideal for a variety of medical applications.

The biggest advantage of these processes is obviously the materials, as DMLS and SLM 3D printers are capable of producing high-performing end-use medical devices and components from metal. These processes can reproduce complex geometries and the finished products are strong, durable, and biocompatible. They can be used to manufacture generic implants (hips, knees, spine implants, etc.), custom implants for cancer or trauma treatment, dentures, as well as medical and orthopedic technology products.

While the prices of metal 3D printers have also begun to decrease, with costs ranging from $200,000 to $1 million+, these systems are still not accessible to most businesses. Metal 3D printing processes also have an involved and complex workflow.

Alternatively, SLA 3D printing is well-suited for casting workflows that produce metal parts at a lower cost, with greater design freedom, and in less time than traditional methods.

The table below highlights the 3D printing technologies that are best equipped to handle the different applications of 3D printing medical devices.

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | Metal 3D Printing (DMLS, SLM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build volume | Up to 300 x 335 x 200 mm (desktop and benchtop 3D printers) | Up to 165 x 165 x 300 mm (benchtop industrial 3D printers) | Up to 300 x 300 x 600 mm (desktop and benchtop 3D printers) | Up to 400 x 400 x 400 mm (large industrial DMLS/SLM) |

| Price range | Starting from $3,750 | Starting from $18,500 | Starting from $2,500 | Starting from $200,000 |

| Materials | Varieties of resin (thermosetting plastics). Standard, engineering (ABS-like, PP-like, silicone-like, flexible, heat-resistant, rigid), castable, dental, and medical (biocompatible). | Engineering thermoplastics, typically nylon and its composites (nylon is biocompatible + compatible with sterilization). | Standard thermoplastics, such as ABS, PLA, and their various blends. | Stainless steel, tool steel, titanium, cobalt chrome, and aluminum. |

| Ideal applications | Highly detailed prototypes requiring tight tolerances and smooth surfaces; molds, tooling, patterns, medical models, functional parts, dental and medical end-use devices. | Complex geometries, functional prototypes, short-run or bridge manufacturing, orthotics, and prosthetics. | Basic proof-of-concept models, low-cost prototyping of simple parts. | Strong, durable parts with complex geometries, implants, dentures, medical and orthopedic components out of metal. |

Depending on the application, biocompatible parts may be required for medical devices. Biocompatibility information is required for 510(k) and premarket approval (PMA) submissions in the United States and other regulatory submissions worldwide. It proves whether the device will be compatible with the biological system in which it is intended. Missing or inadequate information can lead to significant delays in bringing the device to market.

It proves whether the device will be compatible with the biological system in which it is intended. Missing or inadequate information can lead to significant delays in bringing the device to market.

Biocompatibility testing requirements should be determined based on the intended use of the device (type, area, and duration of exposure). Determining testing requirements early in the development process will allow ample time to complete testing before submission to regulatory bodies. It should stem from the expected contact between the device and the human body.

Three different categories typically define contact:

-

Direct Contact: Comes into physical contact with the patient.

-

Indirect Contact: Comes into physical contact with a fluid, gas, or other material that has direct contact with the patient.

-

No Contact: Does not have direct or indirect contact with the patient and is therefore exempt from biocompatibility requirements.

Some 3D printer and 3D printing material manufacturers, like Formlabs, conduct biocompatibility testing based on ISO 10993, ISO 18562, and ISO 7405 standards and publish the information on relevant materials.

As the testing is conducted on standardized printed samples, manufacturers are responsible for following printing and post-processing instructions and for independently validating the biocompatibility of their respective parts.

Webinar

Join Formlabs and Nelson Labs for a deep dive into biocompatibility, including an introduction to our new materials and best practices for medical manufacturers from industry experts.

Watch the Webinar Now

3D printed medical devices must meet the regulatory guidelines in their respective locations.

Part of this process is establishing a quality management system (QMS) which is comprised of the core set of policies, procedures, forms, and work instructions, along with their sequence, interactions, and resources required to conduct business as a medical device company.

Example of QMS hierarchy.

Quality records are documentation that demonstrate the QMS is being executed and followed and describe how your company addresses medical device regulations. The FDA defines the rules in 21 CFR Part 820. And if you plan to go to market in the U.S., these regulations are required.

Outside the U.S., Europe requires a quality system to be established to meet the medical device regulations (and/or IVD regulations). Many medical device companies implement a quality system certified to ISO 13485:2016 to satisfy EU needs.

To learn more about the specific regulatory requirements, download our comprehensive white paper, co-authored by Formlabs partner Greenlight Guru, that includes a variety of resources to support users in each step of the process.

White Paper

This white paper aims to guide users in the medical device industry through every stage of the product development process, from evaluating manufacturing methods and 3D printing technologies to specific regulatory requirements for commercializing and marketing end-use 3D printed medical devices.

Download the White Paper

Webinar

In this webinar, representatives from the FDA, industry, and healthcare discuss recent developments and address some intriguing questions:

Watch the Webinar Now

For medical device firms, in-house 3D printing allows quick iteration cycles, shortening the product development cycle and creating more time for creative solutions.

Every medical facility should have access to the latest tools to improve care and provide the best patient experience. Get started now or expand your in-house production with Formlabs, a proven, cutting-edge partner in medical 3D printing.

Reach out to our medical experts to learn more about how in-house 3D printing can supplement your current medical device design and manufacturing workflow.

Contact Our Medical Experts

Medical 3D printer overview

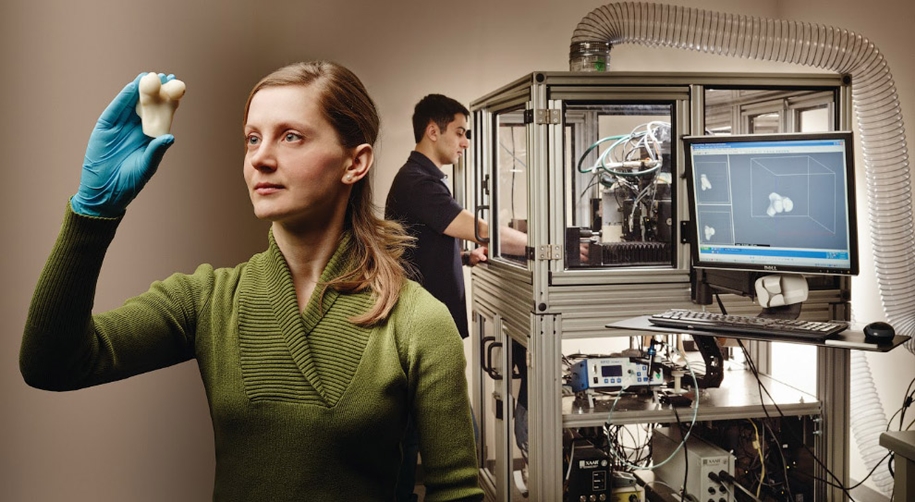

Use of 3D printing in medicine

Source: docwirenews. com

com

3D printing has been used in medicine since the early 2000s, when this technology was first used to make dental implants. Since then, the use of 3D printing in medicine has expanded significantly, with doctors around the world describing ways to use 3D printing to produce ears, skeletal parts, airways, jawbones, eye parts, cell cultures, stem cells, blood vessels and vasculature, tissues and organs, new dosage forms and much more. nine0005

Source: zortrax.com

Using files with models for 3D printing provides an opportunity for the exchange of work among researchers. Instead of trying to reproduce the parameters described in scientific journals, doctors can use and modify ready-made 3D models. To this end, in 2014, the National Institutes of Health established the 3dprint.nih.gov exchange to facilitate the exchange of open source 3D models for medical and anatomical devices, custom equipment, and mock-ups of proteins, viruses, and bacteria. nine0005

nine0005

Source: 3dprint.com

Modern medical use of 3D printing can be divided into several broad categories: tissue and organ fabrication, prostheses, implants and anatomical models, instrument printing, and pharmaceutical research.

Top five uses for 3D printing in medicine

Operational preparation and student education

Source: 3dprint.com

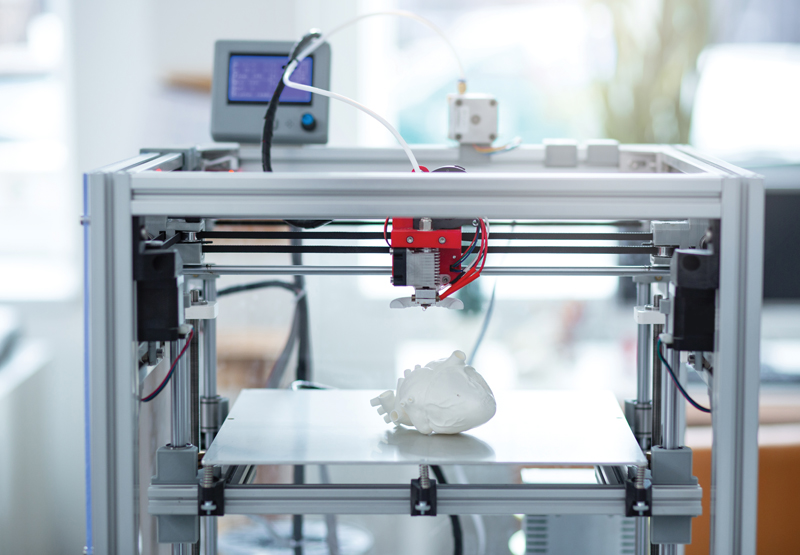

Taking into account individual differences and features of the anatomy of a particular human body, 3D printed models can be used to prepare surgical operations. Having a doctor have a tangible model of a particular patient's organ, made, for example, based on the results of CT (computed tomography) for study or to simulate an operation, significantly reduces the risk of medical errors.

Source: openbiomedical.org

The use of 3D models for training surgeons and students is preferable to training on cadavers, as it does not create problems in terms of availability and cost of objects. Cadavers often lack appropriate pathology, so they are more suitable for anatomy lessons than for presenting a patient with a disorder appropriate to the topic under study. With the help of 3D printing, it is possible to create a model of any organ with any known pathology. nine0005

Source: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

two-dimensional images.

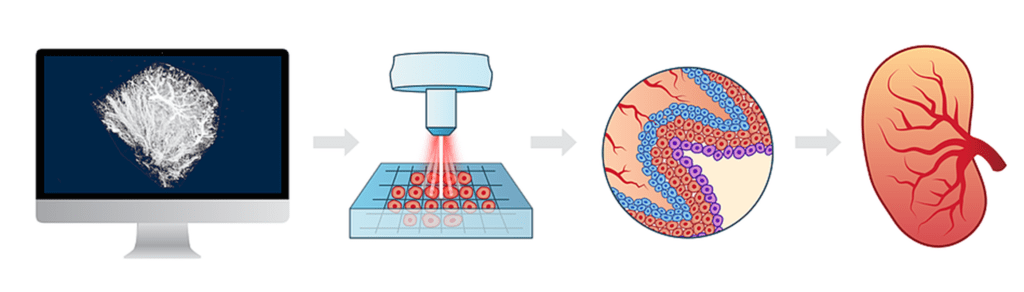

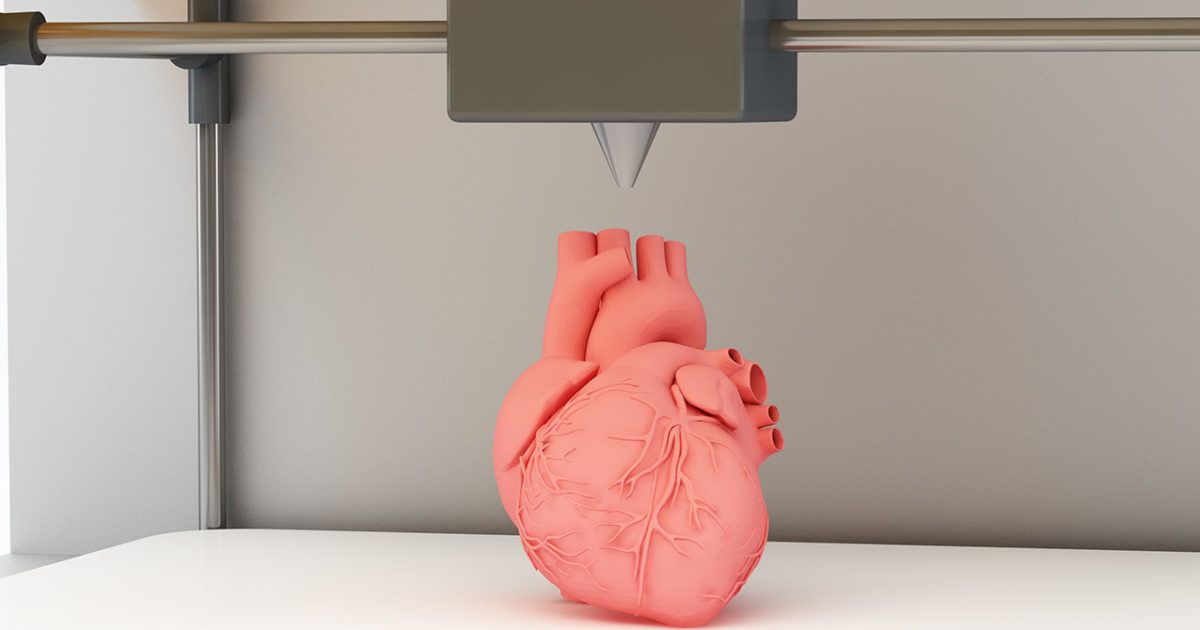

Bioprinting of tissues and organs

Source: hbr.org

Bioprinting is one of the many types of 3D printing used in the medical field. Instead of printing using plastic or metal, bioprinters use a syringe dispenser to apply bioink (layers of living cells or a structuring base for them) to create artificial living tissue. In addition to being used as an alternative to donor tissues, such tissue constructs or organoids can be used for medical research. nine0005

In addition to being used as an alternative to donor tissues, such tissue constructs or organoids can be used for medical research. nine0005

Source: press.ginkgo3d.com

Although 3D bioprinting systems can be laser, inkjet, or extrusion, inkjet bioprinting is the most common. Multiple printheads can be used to accommodate different types of cells (organ-specific, blood vessel cells, muscle tissue), which is a major challenge in the fabrication of heterocellular tissues and organs. 3D printing with biological materials can be used to regenerate tissues, and in the future, organs, directly on the patient. nine0005

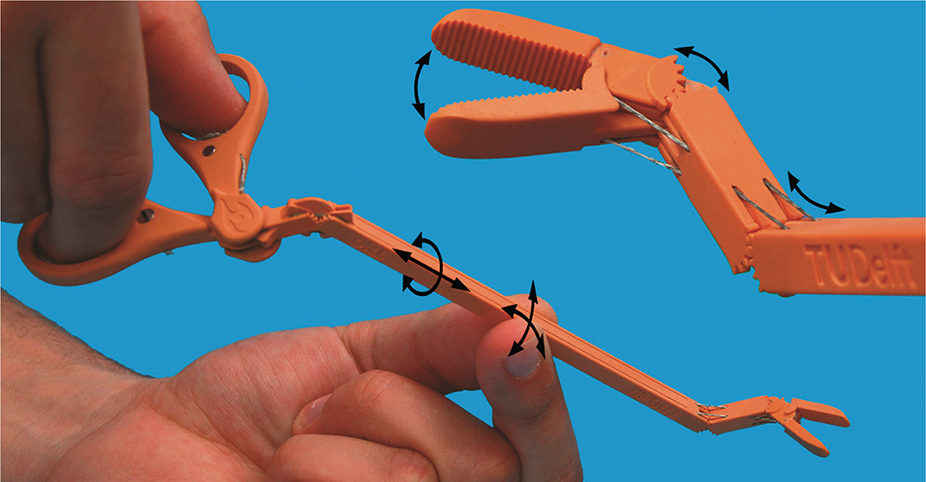

Printing Surgical Instruments

Volt Grip Details, Source: bitegroup.nl

Today's surgeons are trying to perform operations with as little trauma to the patient as possible, so they very often require a personalized instrument. The use of 3D printing makes it possible to create such tools within hours.

The use of 3D printing makes it possible to create such tools within hours.

Volt capture model visualization, Source: bitegroup.nl

Now the doctor can independently modify the finished model, giving it the necessary size and shape for convenience and efficiency. Dentists can now create, for example, individual guides right in front of the patient, eliminating the possibility of damage to healthy teeth during prosthetics.

About the clamp Volt, from the photos above, read further in the section “Examples of use”.

Here's how students at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina create tools using metal 3D printing. nine0005

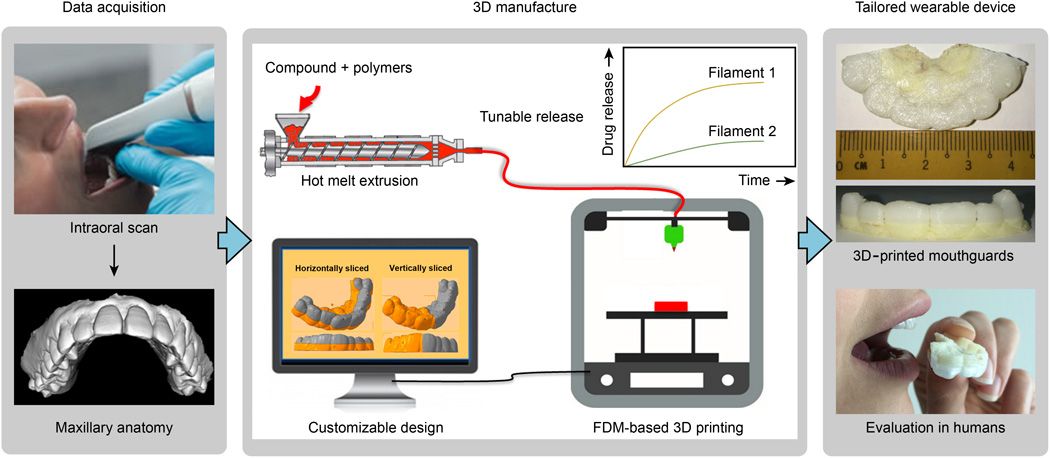

"Printing" drugs

Source: mdpi.com

3D printing technologies are already being used in pharmaceutical research and personalized medicine, and their scope is constantly expanding. 3D printing enables precise dose control of drugs and the production of dosage forms with complex drug release profiles and prolonged action. Now pharmacists can analyze a patient's pharmacogenetic profile and other characteristics such as age, weight, or gender to determine the optimal dose and sequence of medications. If necessary, the dose may be adjusted, depending on the clinical response. With 3D printing, it is possible to produce personalized medicines in completely new formulations, such as tablets containing multiple active ingredients, either as a single mixture or as complex multi-layered tablets. nine0005

3D printing enables precise dose control of drugs and the production of dosage forms with complex drug release profiles and prolonged action. Now pharmacists can analyze a patient's pharmacogenetic profile and other characteristics such as age, weight, or gender to determine the optimal dose and sequence of medications. If necessary, the dose may be adjusted, depending on the clinical response. With 3D printing, it is possible to produce personalized medicines in completely new formulations, such as tablets containing multiple active ingredients, either as a single mixture or as complex multi-layered tablets. nine0005

Prosthetics and Dentistry

Source: eos.info

3D printing has been successfully used in medicine for the manufacture of complex custom prostheses or surgical implants. Implants and prostheses of any possible geometry can be made by converting X-ray, MRI or CT images into a 3D printable model using special software.

The rapid production of custom implants and prostheses solves a pressing problem in orthopedics, where standard implants often do not fit the patient. This is also true in neurosurgery: skulls are individually shaped, so it is difficult to standardize a cranial implant. Previously, surgeons had to use various tools to modify and fit implants, sometimes right during the operation. The use of 3D printers makes this procedure unnecessary. Additive technologies are especially in demand when it is necessary to urgently manufacture implants. nine0005

A real revolution in dentistry came with the advent of 3D technology.

Source: hypowerfuel.com

First, complete and accurate 3D scanning of the oral cavity is now possible. Secondly, the use of 3D printing has made it possible to create prostheses that absolutely fit the anatomy of the patient, without the need for a long and unpleasant fit. The radical reduction in the share of manual labor in the manufacture of prostheses or veneers has reduced the required tolerances in production, expanded the list of materials used and increased patient satisfaction with the results of the doctor's work. nine0005

The radical reduction in the share of manual labor in the manufacture of prostheses or veneers has reduced the required tolerances in production, expanded the list of materials used and increased patient satisfaction with the results of the doctor's work. nine0005

Application examples

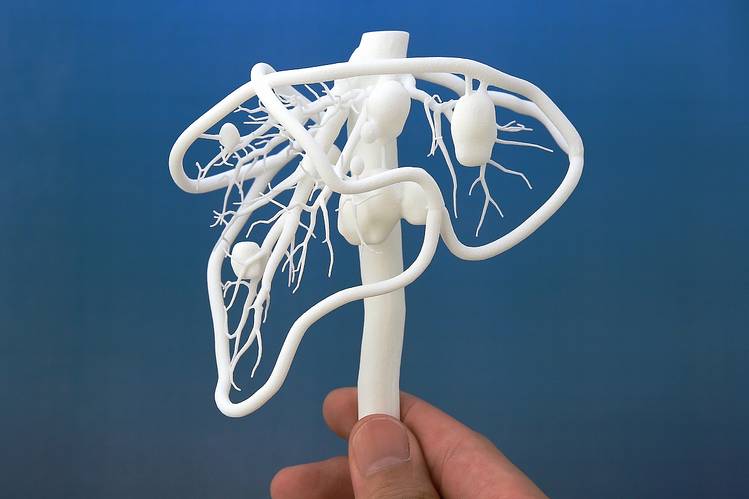

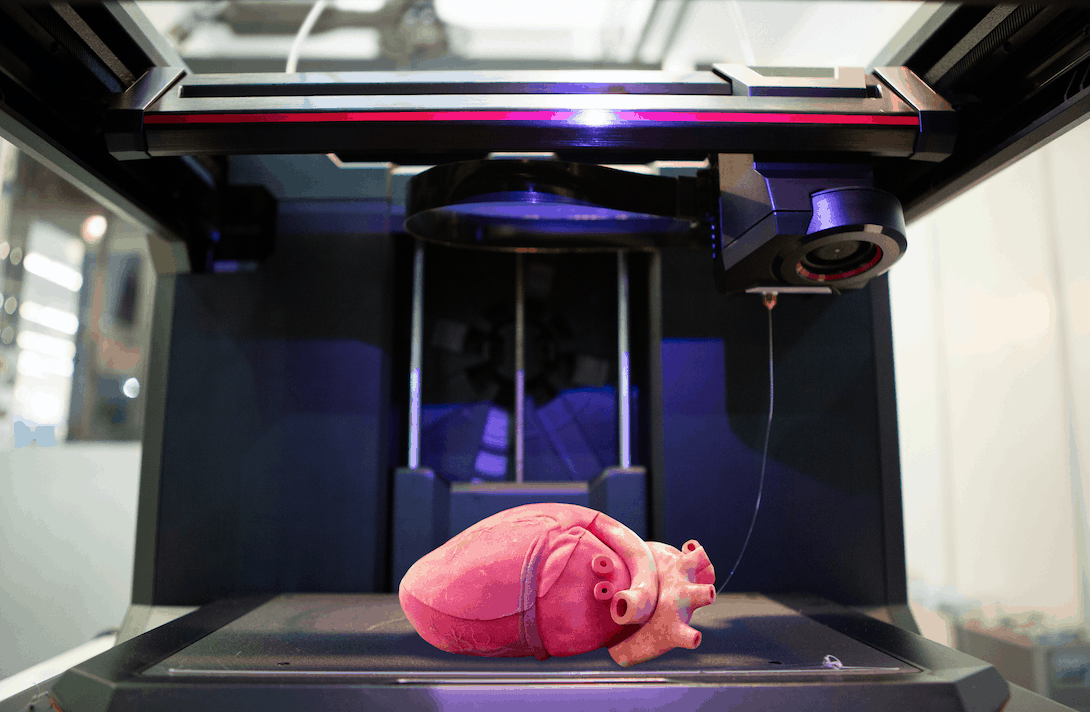

Printing a model of the heart of a four-year-old patient, Zortrax M200 3D printer

In the photo: the assembled heart model. Source: zortrax.com

At the Medical University of Gdansk (Poland) to prepare for an operation to treat a complex congenital heart disease (Fallot's tetrad - malfunction of the pulmonary artery heart valve) in a four-year-old patient, specialists from the Department of Pediatric Cardiology and Congenital Heart Diseases , together with colleagues from the Department of Cardiac Surgery and Radiology, used the Zortrax M200 3D printer. nine0005

nine0005

Photo: artificial pulmonary valve. Source: zortrax.com

The modern method of treatment consists in inserting a catheter through the femoral vein, through which an artificial valve is fed to the heart for implantation. This is a very complex operation that requires the doctor to have detailed knowledge of the individual characteristics of the patient's anatomy.

In the photo: a model of the heart during printing. Source: zortrax.com

Until now, doctors could only rely on a 3D model on a computer screen created from CT and MRI images, and such a reconstruction is not always enough to get a complete picture of the real organ and possible complications . nine0005

Source: zortrax.com

Having a highly detailed tactile model of a patient's living organ in preparation for surgery can be critical to its success. Even experienced surgeons have appreciated the potential of the new technology. Previously, it was difficult to notice individual features and deformations, now it has become tangible and accessible for closer study.

Even experienced surgeons have appreciated the potential of the new technology. Previously, it was difficult to notice individual features and deformations, now it has become tangible and accessible for closer study.

The model was printed within 24 hours. The Z-ULTRAT material was used to print the heart, and the Z-GLASS material was used to print the vessels. After a successful operation, the model was transferred to the University for student training. nine0005

Artificial corneas made on the Nano master SMP-III 3D bioprinter

Source: europepmc.org

In South Korea, about 2000 patients are waiting for corneal donation, and the waiting time for surgery is an average of six years. For patients who cannot find a suitable donor, it is possible to implant artificial corneas consisting of recombinant collagen and synthetic polymers. Unfortunately, they often do not take root and are not completely transparent. This is due to the special structure of the cornea in the form of lattice collagen fibrils, which has not yet been able to be reproduced. A team of researchers from Pohang University of Science and Technology and Kungpuk National University School of Medicine in South Korea have developed a method to 3D print an artificial cornea using patient tissue material. nine0005

This is due to the special structure of the cornea in the form of lattice collagen fibrils, which has not yet been able to be reproduced. A team of researchers from Pohang University of Science and Technology and Kungpuk National University School of Medicine in South Korea have developed a method to 3D print an artificial cornea using patient tissue material. nine0005

Source: ithl.co.kr

3D bioprinter with Nano master SMP-III microextrusion system, Musashi Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, with the following parameters:

-

print speed 130mm/min;

-

extrusion speed 0.0024 mm/s;

-

nozzle diameter 0.29 mm;

-

print temperature 4 °C.

The printed and biofilled cornea was then cultured in an incubator at 37 °C for four weeks. nine0005

nine0005

Source: europepmc.org

A 3D-printed artificial cornea made from decellularized corneal stroma and patient stem cells could completely replace a donor cornea in eye surgery. Since such a cornea is made up of materials derived from the patient's own tissues, it is fully compatible. Cellular 3D printing technology reproduces the natural microenvironment of the eye, which allows to achieve transparency similar to that of the human cornea. nine0005

Pohang University of Science and Technology Professor Jina Jang said:

"We are confident that this technology will restore vision to many patients suffering from corneal diseases."

Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine Mobile 3D printer for treating extensive wounds

the place of the damaged. In addition to the fact that this method is additionally traumatic for the victim, in some cases there may not be healthy skin left on the body at all for use. Wake Forest School of Medicine has developed a printer that can print skin cells grown from patient tissue directly onto a wound. nine0005

Wake Forest School of Medicine has developed a printer that can print skin cells grown from patient tissue directly onto a wound. nine0005

Source: 3dnatives.com

The ZScanner Z700 handheld 3D scanner is used to determine the size and depth of a wound. Based on this information, the 3D printer prints subcutaneous, dermal and epidermal skin cells at appropriate depths to completely cover the wound.

Source: 3dnatives.com

The 3D bioprinting system developed by scientists consists of a three-axis moving print head with eight 260 micron diameter nozzles with independent dispensers. Specifically for this device, the researchers created a bioink consisting of autologous dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes in a hydrogel carrier. nine0005

Bite

Volt Bipolar Surgical Forceps for Laparoscopic Surgery stop bleeding during surgery. It was created for use in minimally invasive (sparing) surgery in 2016 and successfully tested on pig liver. nine0005

It was created for use in minimally invasive (sparing) surgery in 2016 and successfully tested on pig liver. nine0005

Source: bitegroup.nl

The design of the device allows easy adjustment of the shaft and tip geometry depending on the patient's anatomy and surgical requirements. Maneuverable shank - ±65° for lateral movements and ±85° up and down. Flexural stiffness of 4.0 N/mm for connection 1 and 4.4 N/mm for connection 2, significantly higher than previously available guided tools. The tip consists of two 3D printed titanium movable jaws with an opening angle of up to 170°. The instrument is connected to an Erbe electrosurgical unit and is able to successfully coagulate tissue at a temperature of 75 °C, reached in 5 seconds. nine0005

Conclusion

Source: intermercados.com.br

The use of additive technologies in medicine is expanding so rapidly that it is more like a revolution in healthcare. The use of 3D printing in medicine enables the individualization of medical devices, medicines and equipment, increases cost efficiency and productivity, reduces waiting times for patients and improves the availability of medical care. nine0005

The use of 3D printing in medicine enables the individualization of medical devices, medicines and equipment, increases cost efficiency and productivity, reduces waiting times for patients and improves the availability of medical care. nine0005

Source

Tags:

3D printing in medicine, dental implants, 3D printing for ear production, 3D printed models, Surgical instrument printing, Drug printing, Prosthetics and dentistry , Zortrax M20 3D Printer

5 innovative applications of 3D printing in medicine

Personalized and precise solutions in the medical field are becoming increasingly popular. New tools and advanced technologies bring doctors closer to patients by providing treatments and devices that meet the needs of each individual. nine0005

The expansion of 3D printing technologies in healthcare has made a huge contribution to improving the quality of medical services. With new tools and treatment approaches developed using 3D printing, patients feel that their treatment becomes more comfortable and personal. For physicians, the new technology available allows them to better analyze complex cases and provides new tools that can ultimately raise standards of care.

With new tools and treatment approaches developed using 3D printing, patients feel that their treatment becomes more comfortable and personal. For physicians, the new technology available allows them to better analyze complex cases and provides new tools that can ultimately raise standards of care.

Later in this article, you'll learn about five areas, from models for surgical planning to vascular systems and bioreactors, in which 3D printing is used in healthcare, and why many healthcare professionals see great potential in this technology.

In today's medical practice, 3D printed anatomical models based on patient body scans are becoming more indispensable tools, as they provide more personalized and accurate treatment. As cases become more complex and standard case times become more important, visual and tactile anatomical models are helping surgeons to better understand their task, communicate more effectively, and communicate with patients more easily. nine0005

Medical professionals, hospitals and research institutes around the world use 3D printed anatomical models as a reference tool for preoperative planning, intraoperative imaging, and for sizing medical instruments or presetting equipment for both standard and very complex procedures, which is reflected in hundreds of scientific publications.

3D printing makes 3D printing affordable and easy to create customized patient anatomical models based on CT and MRI data. The peer-reviewed scientific literature demonstrates that they help clinicians better prepare for surgery, resulting in significant cost and time savings. At the same time, patient satisfaction is also increased through reduced anxiety and reduced recovery time. nine0005

Physicians can use individual patient anatomical models to explain the procedure to the patient, making it easier to obtain patient consent and reduce patient anxiety.

Preparation for surgery using preoperative models can also affect the effectiveness of the treatment. The experience of Dr. Michael Ames confirms this. After obtaining bone replications from the young patient's forearm, Dr. Ames realized that the injury was different from what he expected.

Based on this information, Dr. Ames chose a new soft tissue procedure that was much less invasive, reduced downtime, and resulted in much less scarring. Using imprinted bone replication, Dr. Ames explained the procedure to the young patient and his parents and obtained their consent. nine0005

Using imprinted bone replication, Dr. Ames explained the procedure to the young patient and his parents and obtained their consent. nine0005

Physicians can use patient-specific surgical models to explain the procedure beforehand, improving patient consent and lowering anxiety.

Result? The operation lasted less than 30 minutes instead of the originally planned three hours. With this reduction in operating time, the hospital avoided a cost of about $5,500 and the patient recovered faster.

According to Dr. Alexis Dang, Orthopedic Surgeon at UC San Francisco and Veterans Affairs Medical Center San Francisco: “All of our full-time orthopedic surgeons and almost all of our full-time surgeons part-time, used 3D printed models to treat patients at a Veterans Medical Center in San Francisco. We could all see that 3D printing improves the efficiency of our work.” nine0005

The advent of new biocompatible medical polymers for 3D printing has opened up opportunities for the development of new surgical instruments and techniques to further improve clinical operating procedures. These include sterilizable trays, contoured surgical guides, and implant models that can be used to determine the size of an implant prior to surgery, helping surgeons reduce time and improve accuracy in complex procedures.

These include sterilizable trays, contoured surgical guides, and implant models that can be used to determine the size of an implant prior to surgery, helping surgeons reduce time and improve accuracy in complex procedures.

Anatomical model of a hand with elastic polymer skin for 3D printing. nine0005

Todd Goldstein, PhD, lecturer at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, is unequivocal about the importance of 3D printing technology to the work of his department. He estimates that if Northwell used 3D-printed models 10-15% of the time, it could save $1,750,000 a year.

“Whether it's prototyping medical devices, complex anatomical models for our children's hospital, designing training systems, or making surgical templates for dental clinics, [3D printing technology] has increased our capabilities and reduced our costs in a variety of areas. In doing so, we were able to produce instruments for treating patients that would be almost impossible to recreate without our sought-after stereolithography 3D printer,” says Goldstein. nine0005

nine0005

3D printing has become virtually synonymous with rapid prototyping. The ease of use and low cost of 3D printing in-house has also revolutionized product development, with many medical instrument manufacturers adapting the technology to produce entirely new medical devices and surgical instruments.

More than 90 percent of the top 50 medical device companies use 3D printing to create accurate medical device prototypes and fixtures and fittings to simplify testing. nine0005

According to Alex Drew, Principal Mechanical Engineer for DJO Surgical, an international medical device supplier, “Before DJO Surgical purchased [Formlabs' 3D printer], we printed almost all of our prototypes outsourced. Today we are working with four Formlabs printers and are very pleased with the results. The speed of 3D printing has doubled, the cost has been reduced by 70%, and the level of detail allows you to effectively coordinate designs with orthopedic surgeons. nine0005

Medical companies such as Coalesce are using 3D printing to create accurate medical device prototypes.

3D printing helps speed up the design process by allowing complex designs to be iterated in days instead of weeks. When Coalesce was tasked with building an inhaler device that could digitally evaluate an asthma patient's inspiratory flow profile, outsourcing would result in a significant increase in production time for each prototype. Before sending the project files to a third party company for the physical implementation of the project, they would have to be carefully developed and carried through various iterations. nine0005

Instead, desktop stereolithographic 3D printing allowed Coalesce to handle the entire prototyping process in-house. The prototypes were suitable for use in clinical trials and looked just like the finished product. Moreover, when the company demonstrated the device, its customers mistook the prototype for the final product.

Overall, the introduction of in-house manufacturing resulted in an exceptional reduction in prototyping time by 80–90%. In addition, the models took only eight hours to print and were finished and painted in a matter of days, while outsourcing the same process would take a week or two.

In addition, the models took only eight hours to print and were finished and painted in a matter of days, while outsourcing the same process would take a week or two.

Hundreds of thousands of people lose limbs every year, but only a fraction of them are able to restore limb function with a prosthesis.

Conventional dentures are only available in a few sizes, so patients must adjust to what fits best. On the other hand, custom bionic prostheses that mimic the movements and grips of a real limb based on the impulses of the surviving limb muscles are so expensive that they can only be used by patients living in developed countries with the best medical insurance. In the case of children's prostheses, the situation is aggravated even more. Children grow up and inevitably outgrow their prostheses, which, as a result, require costly modifications. nine0005

The difficulty lies in the lack of manufacturing processes that would allow for individual orders at an affordable price. But increasingly, prosthetists are looking to reduce these high financial barriers to rehabilitation with the flexible design capabilities of 3D printing.

But increasingly, prosthetists are looking to reduce these high financial barriers to rehabilitation with the flexible design capabilities of 3D printing.

Initiatives like e-NABLE allow people around the world to learn about the possibilities of 3D printed prostheses. They are driving an independent movement in the prosthesis industry by offering information and free open source projects so that patients can get a custom-designed prosthesis for as little as $50. nine0005

Other inventors like Lyman Connor go even further. With only a small fleet of four desktop 3D printers, Lyman was able to fabricate and customize his first mass-produced prostheses. His ultimate goal? Create a customizable fully bionic arm that will cost incomparably less than similar prostheses that retail for tens of thousands of dollars.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have also found that 3D printing is the best method for making more comfortable prosthetic sockets. nine0005

In addition, the low cost of manufacturing these prostheses, as well as the freedom that comes with the ability to design custom designs, speak for themselves. 3D printed prostheses have a lead time of just two weeks, and then they can be tried and serviced at a much lower cost than traditional counterparts.

3D printed prostheses have a lead time of just two weeks, and then they can be tried and serviced at a much lower cost than traditional counterparts.

As costs continue to fall and material properties improve, the role of 3D printing in healthcare will no doubt become more important. nine0005

The same high financial barriers that are seen in prosthetics are common in orthoses and insoles. Like many other patient-specific medical devices, custom-made orthoses are often not available due to their high cost and take weeks or months to manufacture. 3D printing solves this problem.

Confirmation is the example of Matej and his son Nick. Nick was born in 2011. Complications during preterm birth led to the fact that he developed cerebral palsy, a pathology that affects nearly twenty million people worldwide. Matei was delighted with how determined his son was to overcome the limitations of his illness, but he was faced with a choice between a standard, off-the-shelf orthosis that would be uncomfortable for his son, or an expensive custom solution that would take weeks or months to manufacture and ship. , and from which the child would quickly grow. nine0005

, and from which the child would quickly grow. nine0005

He decided to take matters into his own hands and began to look for new ways to achieve his goal. Thanks to the opportunities provided by digital technologies, in particular 3D scanning and 3D printing, Matei and Nika's physiotherapists were able to develop a completely new innovative workflow for the manufacture of ankle orthoses through experiments.

The resulting 3D-printed, custom-fit orthosis that provides support, comfort, and motion correction helped Nick take his first steps on his own. This non-standard orthopedic device reproduced the functionality of the highest-class orthopedic products, at the same time it cost many times less and did not require any additional settings. nine0005

Professionals around the world are using 3D printing as a new method of manufacturing custom insoles and orthoses for patients and clients, as well as a range of other physiotherapy tools. In the past, undergoing a course of physiotherapy with the use of individual physiotherapy instruments carried many difficulties. Often there was a situation when patients had to wait a long time for a finished product, which at the same time did not provide proper comfort. 3D printing is step by step changing this status quo. Data confirms that 3D printed insoles and orthoses offer a more precise fit and lead to better therapeutic outcomes, which means greater comfort and benefit for patients. nine0005

Often there was a situation when patients had to wait a long time for a finished product, which at the same time did not provide proper comfort. 3D printing is step by step changing this status quo. Data confirms that 3D printed insoles and orthoses offer a more precise fit and lead to better therapeutic outcomes, which means greater comfort and benefit for patients. nine0005

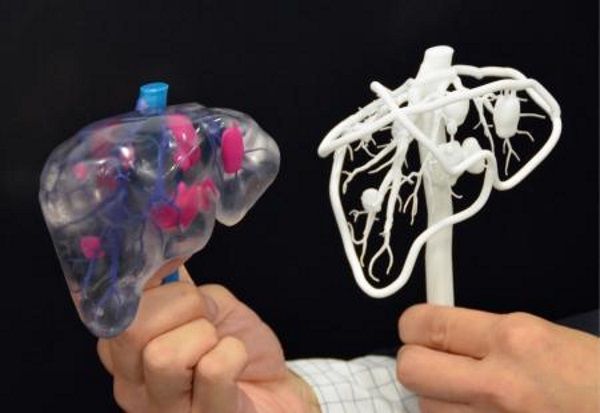

The usual treatments for patients with severe organ damage today are autografts, transplantation of tissue from one area of the body to another, or transplantation of a donor organ. Researchers in bioprinting and tissue engineering hope to expand this list soon with on-demand fabrication of tissues, blood vessels, and organs.

3D bioprinting is an additive manufacturing process that uses materials known as bioink (a combination of living cells and a compatible substrate) to create tissue-like structures that can be used in medicine. Tissue engineering combines new technologies, including bioprinting, which make it possible to grow replacement tissues and organs in the laboratory for use in the treatment of injuries and diseases. nine0005

nine0005

Using high-precision 3D printing, researchers such as Dr. Sam Pashne-Tala from the University of Sheffield are breaking new ground in tissue engineering.

In order to direct cell growth to form the necessary tissue, Dr. Pashne-Tala grows living cells on a laboratory scaffold that provides a template of the required shape, size and geometry. For example, to create a blood vessel for a patient with cardiovascular disease, a tubular structure is needed. The cells will multiply and cover the scaffold, taking on its shape. Then the scaffold is gradually destroyed, and the living cells take the form of the target tissue, which is cultured in a bioreactor - a chamber that contains the cultured tissue and can reproduce the internal environment of the body so that the cultured tissue acquires the mechanical and biological characteristics of organic tissue. nine0005

3D printed bioreactor chamber with tissue engineered aorta miniature inside. The tissue is cultured in a bioreactor to acquire the mechanical and biological characteristics of the organic tissue.

3D printed bioreactor chamber with tissue engineered aorta miniature inside. The tissue is cultured in a bioreactor to acquire the mechanical and biological characteristics of the organic tissue.

This will allow scientists to design patient-specific vascular grafts, expand surgical care, and provide a unique platform for testing new vascular medical devices for people suffering from cardiovascular disease, which is currently the leading cause of death worldwide. The ultimate goal is to create blood vessels that are ready for implantation in patients. Since tissue engineering uses cells taken from a patient in need of treatment, this eliminates the possibility of rejection by the immune system, which is the main problem of modern transplantology. nine0005

3D printing has proven its ability to solve the problems that exist in the production of synthetic blood vessels, in particular, the difficulty of recreating the required accuracy of the shape, size and geometry of the vessel. The ability of printed solutions to clearly reflect the specific characteristics of patients was a step forward.

The ability of printed solutions to clearly reflect the specific characteristics of patients was a step forward.

According to Dr. Pashne-Tal: “[Creating blood vessels using 3D printing] makes it possible to expand the possibilities of surgical care and even create designs of blood vessels for a specific patient. Without the existence of high-precision affordable 3D printing, the creation of such forms would not be possible.” nine0005

We are witnessing significant advances in the development of biological materials that can be used in 3D printers. Scientists are developing new hydrogel materials that have the same consistency as organ tissues present in the human brain and lungs, which can be used in a range of 3D printing processes. Scientists hope that they will be able to implant them into the body as a "scaffold" for cell growth.

Although bioprinting of fully functional internal organs such as the heart, kidneys and liver still looks futuristic, hybrid 3D printing at very high speed opens up more and more new horizons. nine0005

It is expected that sooner or later the creation of biological matter on laboratory printers will lead to the generation of new, fully functional 3D printed organs. In April 2019, scientists at Tel Aviv University 3D-printed the first heart using biological tissue from a patient. A tiny copy was created using the patient's own biological tissues, which made it possible to fully match the immunological, cellular, biochemical and anatomical profile of the patient. nine0005

“At this stage, the heart we printed is small, the size of a rabbit heart, but normal-sized human hearts require the same technology,” says Prof. Tal Dvir.

The first 3D bioprinted heart created at Tel Aviv University.

Precise and affordable 3D printing processes, such as desktop stereolithography, are democratizing access to technology, enabling healthcare professionals to develop new clinical solutions and quickly produce medical devices with individual characteristics, and doctors around the world to offer new types of therapy.